Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 26, Number 3 (September 2020)

Review of A Hidden Life, written and directed by Terrence Malick (Fox Searchlight 2019)

By Lauren Faulkner Rossi

The Extraordinary Stance of an Ordinary Man

Scholarship tells us that the German military authorities executed tens of thousands of men and jailed hundreds of thousands more during the Second World War for the crime of Wehrkraftzersetzung, or the undermining of military morale.[1] Such a category encompassed a broad spectrum of treasonous behaviour, from deliberate sabotage to desertion of one’s post to conscientious objection. Franz Jägerstätter is one of the more well-known examples of the last category. Gordon Zahn’s 1964 English-language biography, In Solitary Witness, brought him renown beyond his immediate community and did much to illuminate the historical and moral circumstances of Jägerstätter’s life and especially his execution. Numerous articles, books, and screen treatments of him followed over several decades, leading to the 1998 formal abrogation of his sentence and his 2007 beatification by Pope Benedict XVI, who also recognized him as a martyr.[2] Terrence Malick’s exploration, therefore, does not necessarily break new ground, but the strength of the film, as it retreads established paths, is the director’s attention to the emotional toll of Jägerstätter’s conviction on himself and his family, and the director of photography’s breathtakingly beautiful shots of the South Tyrol alpine countryside.[3]

Malick is an atypical American director: he has protected his private life to the point of reclusiveness; his projects routinely consume several years; while he has made several critically-acclaimed films (his first film, Badlands; The Thin Red Line, about the Vietnam War; The Tree of Life, about immortality), he is both lauded and criticized for favouring themes and visual aesthetics over plot and narrative (see The Tree of Life). In fact, A Hidden Life delivers a more linear narrative than many of his films, with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end. It opens with Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, the famous aerial shot of clouds and a city gradually coalescing through the mist. Lasting only the first couple of minutes, and including splices from elsewhere in that famous 1934 documentary, such as the stunning panorama of the Nazi Party’s rally grounds, this is all Malick gives to the audience of Hitler’s climb to power and takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia before plunging directly into the fall of 1939. Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) is married to Franziscka (“Fani”, Valerie Pachner), and has two small blonde-haired, blue-eyed daughters. They live in the Upper Austrian village of Sankt Radegund, not far from the German border (Bavaria). We watch them pause in their labour as unseen planes fly overhead, our only clue that the war has begun.

Malick is an atypical American director: he has protected his private life to the point of reclusiveness; his projects routinely consume several years; while he has made several critically-acclaimed films (his first film, Badlands; The Thin Red Line, about the Vietnam War; The Tree of Life, about immortality), he is both lauded and criticized for favouring themes and visual aesthetics over plot and narrative (see The Tree of Life). In fact, A Hidden Life delivers a more linear narrative than many of his films, with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end. It opens with Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, the famous aerial shot of clouds and a city gradually coalescing through the mist. Lasting only the first couple of minutes, and including splices from elsewhere in that famous 1934 documentary, such as the stunning panorama of the Nazi Party’s rally grounds, this is all Malick gives to the audience of Hitler’s climb to power and takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia before plunging directly into the fall of 1939. Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) is married to Franziscka (“Fani”, Valerie Pachner), and has two small blonde-haired, blue-eyed daughters. They live in the Upper Austrian village of Sankt Radegund, not far from the German border (Bavaria). We watch them pause in their labour as unseen planes fly overhead, our only clue that the war has begun.

Their life as farmers (some scholars call them peasants) can be backbreakingly hard, a fact that Malick and Jörg Widmer, the director of photography, take great care to emphasize continuously, so one cannot charge the film with romanticizing rural workers. Their existence is dominated by the seasons, and harvests, and very dependent on the cooperation of the entire community: cutting and milling wheat, ploughing fields without advanced machinery, tending sheep and other farm animals, pulling dirt and mud out of a dried-up well by hand. But there is also an authenticity in their labour and a simplicity to their daily routine: planting potatoes, picking fruit from trees, their daughters underfoot or at their sides, the frequent daytime breaks for quiet moments together or to play games, window frames and sills decorated with fresh wildflowers. The mountains are quasi-protagonists themselves, looming in and out of view in the wide-angled shots that Malick favours in many of his features, emphasizing the grandiosity and majesty of nature and the relative insignificance of humans.

Malick ensures that this visually arresting scenery is firmly implanted in his audience as he continues towards the middle of his narrative. Franz – well liked, an upstanding member of his community, a family man – undertakes compulsory military training in 1940 (around which time a third daughter arrives), at first with benign acceptance but then with increasing doubt. Documentary footage from the battlefield, shown as part of training, leaves a deep and obviously negative impression on him, and he returns home full of doubt about his willingness and ability to serve. (The film does not make this clear, but he received an exemption as a farmer and would not be called up until 1943.) His doubts are rooted in the unjustness of the war and the conduct of the German Wehrmacht, though Malick seems less interested in historical context and more in the emotional, almost visceral angst of Franz. The real-life Jägerstätter’s objections were more than mere hostility to the war effort, had a much longer brewing period – he was the only person in his village to vote against the Anschluss in 1938 – and had as much to do with the nature of the Nazi regime as the war itself. He condemned the Nazi T4 “euthanasia” program when he learned of it and followed with dismay the repeated and open attacks by the Nazis on the Catholic Church in both Germany and Austria, which further estranged him from the idea of military service.

His struggle is conducted internally and externally; in the film, in addition to countless wordless scenes of long gazes and conflicted expressions, there is almost no one that Franz does not eventually seek out for counsel. He speaks with his wife and his mother, Rosalia. (He was her only son, and she did not initially support his decision.) He speaks with his local priest in the church where he works as sacristan (and where he became a member of the Third Order of Saint Francis, a fact not mentioned in the film), who nervously tells him, “Your sacrifice would benefit no one”, but nonetheless arranges for him to meet with Josef Fließer, bishop of Linz. The bishop tells him, “You have a duty to the Fatherland – the Church tells you so.” (Franz confides to his wife that he felt the bishop treated him as a potential spy and feared to speak openly.) He defends himself to the mayor, once a friend, and to the former mayor, and to the miller, and to a painter working on the church frescoes, and to others who would listen. The earlier emphasis on community now reveals itself for its significance: if that community should turn against you, the bleakness of life tending a farm in such remote conditions is acute. Franz finds no true like minds and almost no supporters, and his family is actively ostracized and jeered at for his “act of madness, [his] sin against family and village.” His wife and her sister, Resie, must endure bullying and fits of shouting; his children are picked on. The mayor calls him a traitor to his face. The few people that show an understanding continue their friendships discreetly, from a distance. For his part, Franz is not swayed from his conviction: he knows he will not take the oath to Hitler – “the anti-Christ,” as one of the very few sympathetic villagers refers to him, in a soft tone – that is required of all soldiers; he refuses to give donations to veterans’ associations, whose brown-shirted members are canvassing for money; he refuses the Hitler greeting, clinging obstinately to the regional “Grüß Gott” that one still encounters there today. He and Fani hope that the war will be over before he is called up, and talk about possibly running away, maybe hiding in the forest. (Fani eventually encounters a bedraggled, dirt-crusted man, a stranger and, one assumes, a Jew, in the forest near the village, but he flees before she can approach. There are no Jews in the movie and no mention of the word Jew itself, only vague allusions to unwanted foreigners during one of the mayor’s drunken monologues shrieked before a blazing outdoor fire.) Franz does not seem to have seriously considered this. In any case, his fate cannot be delayed long.

Franz is called up in March 1943, in the aftermath of the disastrous German defeat at Stalingrad (Malick does not mention this context). In short order, Franz refuses the oath and is tossed into jail, first at Enns where he underwent training, and then later at Tegel, in Berlin. Here is where Malick comes closest to showcasing the violence and sadism of Nazism, in the form of Franz’s military guards who subject him to endless beatings, torture, and other cruelties. The windows of the cells he is moved through grow gradually smaller until he is held in a space scarcely larger than a closet with a tiny window he cannot reach. Such claustrophobic confinement is contrasted with his memories of home, the sweeping meadows, the trees with low-hanging fruit, and even more dramatically by Malick’s insertion of colourized documentary footage of Hitler at his mountain retreat in Berchtesgaden, entertaining the Nazi elite and their children, or sitting contemplatively in a chair with the mountains looming behind him.

Both Franz and Fani are subjected to temptations: the suave lawyers who try to persuade Franz to change his mind, and Resie, who insists to Fani that Franz’s behaviour is prideful and selfish. Where Fani’s faith comes across as childlike, perhaps even naïve – “No evil can happen to a good man,” she tells herself as she waits to hear the outcome of her husband’s arrest – Franz’s is presented as more complex, and, not surprisingly, more tortured. Any comparison of suffering is mostly an unhelpful exercise, because without doubt both of them suffered, if in different ways: beyond the endless waiting and uncertainty, Fani has only Resie for help through one springtime since no one from the village would work for them, and eventually was loathe even to go to church, where she had to endure the unwelcoming stares of her neighbours. As for Franz, his mental state begins to deteriorate rapidly, salvaged only briefly by the reappearance of Waldlan, a friend from basic training who also ended up in Tegel. (Not much by way of explanation is given: “What are you here for?” “Treason.”) Waldlan’s childlike demeanour and goofy smile leads to one of the film’s more tender, introspective moments as he stares out of his jail cell window, speaking to Franz of being free, planting vines to make wine (a white wine for summer, a red wine for winter), and sometimes going to church, and sometimes staying home.

The denouement is a foregone conclusion, even if the audience is not familiar with Franz’s story: he appears before a military tribunal, having declined numerous times to volunteer for service in a medical unit as a way to save himself. (In fact, the real Franz Jägerstätter was willing to serve in a non-arms-bearing capacity, but this was evidently ignored at his trial.[4]) He is screamed at by a junior official, and taken to the senior judge’s private chambers during a recess and gently questioned there about his position. The conversation between Franz and the judge, played by the indomitable Bruno Ganz (famous among North American audiences for playing Hitler in Der Untergang, here in one of his final roles), is almost as affecting as Widmer’s mountain shots: Ganz as the judge lets sober contemplation and discomfort play across his face and, after Franz is returned to the courtroom, he sits down in the chair he had occupied, hands on knees, silent, as if trying to imagine himself in Franz’s place. Ultimately, he is not moved enough to challenge the inevitable: Franz is sentenced to death, and executed by guillotine on 9 August 1943.

Cinematically, this is the most beautiful film I have seen this year, and maybe for several years. Malick and Widmer are famous for such productions. Even if one expects a visual spectacle based on their reputation, to experience the camera following closely behind Franz’s motorcycle on the sun-soaked mountain path, skimming through rolling fields, past simple shrines and straw-hatted labourers packing hay, is breathtaking. Fani’s search for firewood in the winter of 1940/41, while Franz is undergoing training, is similarly arresting, as she trudges alone over streams and up hills through waist-high snow. The pacing is even and unrushed, and while there is very little action (in the American sense), the three hours was not arduous. The two lead actors are convincing in both their love for and dedication to each other as well as the anguish that Franz’s position causes. Malick is hardly a stranger in confronting the deeply spiritual and philosophical conundrums of our time and exploring the repercussions of an individual’s difficult decision, particularly on loved ones. His camera lingers on Franz’s face, anxious to catch any evidence of doubt or regret (one senses it but never quite sees it), and exposes us to Fani’s breakdown, her hands ripping into the earth in vain, her fists and feet pummeling the unyielding wood of the pasture fence before climbing over it and running into the distance. The impressive supporting cast adds heft to the drama: in addition to Ganz, appearances are made by Matthias Schoenaerts as one of Franz’s lawyers, Jürgen Prochnow as the former mayor, Michael Nyqvist as Bishop Fließer, Karl Markovics as the mayor, and Franz Rogowski as Waldlan. Malick deftly uses language to convey various moods as well: the movie is in English with un-subtitled German threaded into specific scenes, including the trial and community gatherings. But this is not Hollywood’s take on the shrieking Nazi, the German rendered villainous and almost unintelligible; there is that too, as the villagers holler at Fani and Resie in guttural, spit-flecked Austrian dialect, but Malick also uses it for Franz’s whispered prayers and Bible recitations, and Fani’s own musings, prayers and half-thoughts, both sprinkled throughout the movie.

The critical eye of the historian will be less generous in her assessment of the film, though clearly Malick made decisions as the writer and director without feeling obliged to honour the deeper historical context. Franz and Fani are presented as partners, but his decision to refuse the oath is his own. Historically Franziska Jägerstätter endured much controversy and was depicted in her community both at the time and for many years after the war as a co-conspirator, maybe even an arch-influencer, in Franz’s decision; the fact that she supported him, even encouraged him to stand his ground (relayed in the film as her swearing, in the wrenching final meeting between them sometime before his trial, that she would love him no matter what he chose to do) was read by many as having fueled Franz to commit himself to his conscientious objection. She was the more religious of the two when they married; he became more serious about his faith after they wed. This gives a deeper meaning to one of the only exchanges with words between Fani and Rosalia, when she asks her mother-in-law if she blames her for her son’s actions; Rosalia responds cryptically, “He was different, before he met you,” and then the scene cuts away. He was also significantly affected by the example of Franz Reinisch, a fellow Austrian conscientious objector and the only Catholic priest to be executed during the Third Reich, in August 1942, for refusing to swear the Hitler oath; Franz found great affirmation in the fact that he was following the example of a priest. Reinisch plays no role in the movie. Nor does Rupert Mayr, another member of the Third Order of Saint Francis and fellow conscientious objector, who Franz met during his training; the two grew very close through a voluminous correspondence. Rather, Malick presents Franz as something of a lone wolf in his principled stance.

The film is clearly the story of Franz and, to a slightly lesser extent, Fani, and their emotions. Thus Malick spends little time delving into the motivation behind Franz’s decision, beyond his disgust with the war and rejection of Hitler. Their deep religiosity is evident, as is Franz’s desire to be guided by authorities in his church and his belief that what he is doing is right. But the true cause of his refusal to swear the oath – his conviction that, as a Catholic he could not in good conscience swear loyalty to a man like Hitler and the regime he represented, both of which were antithetical to all that a faithful Catholic held as central – is not as deeply interrogated as his emotional journey to stay faithful to that refusal. We do not really learn how he came to feel this way. We know nothing of Franz before 1939 other than brief flashbacks centred on Fani, and we are left to assume what exactly his objections are to Nazism. There is no evidence in the film that Franz wrote extensively, but he did, both about his faith (including, evidently, a catechism for his children, in fearful anticipation that they would not receive a proper Catholic education; his parish priest burnt it in 1945[5]) as well as his opposition to Nazism. Malick’s Franz holds a pencil only to write a few last lines, presumably to Fani, on a clipboard that a guard thrusts at him as he stands waiting for his sentence to be carried out. Even less time is spent on the Church authorities that Franz trusted and who forsook him: the bishop in Linz and the parish priest in Sankt Radegund both come across as typical clergy for the time, careful not to speak openly against the regime, content to stress one’s duty to nation, community and family. Why they failed to share Franz’s conviction that one could not compromise with Nazism without endangering one’s soul is a question still debated today, with few satisfying answers: why did he resist, but not these others? Why was accommodation to Nazism far more common than resistance?

But A Hidden Life, while based on true events and largely accurate to those events as documents tell us, does not pretend to be a rigid historical rendering. Malick is intent on sketching a portrait of Franz and the depth and breadth of his humanity. Each scene was prepared to show the extraordinary goodness of an ordinary man in exceptional circumstances, who was killed for refusing to compromise his deepest beliefs. (An epigraph featuring a George Eliot quotation, unidentified as from Middlemarch, clarifies the meaning of the title.) For this reason the film may well be one of Malick’s masterpieces, bringing the story of Franz Jägerstätter to a more popular audience, and giving to a more informed, scholarly audience a nuanced, reverent treatment of one of the era’s few genuine heroes.

Notes:

[1] See Norbert Haase and Gerhard Paul, Die andere Soldaten : Wehrkraftzersetzung, Gehorsamsverweigerung, und Fahnenflucht im Zweiten Weltkrieg (Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1995).

[2] A concise but detailed analysis of the abrogation is delivered by Manfred Messerschmidt, « Die Aufhebung des Todesurteils gegen Franz Jägerstätter » in Kritische Justiz 31/1 (1998), 99-105.

[3] Because of the amount of literature on Franz Jägerstätter, some of which is academic and much of which is hagiographic, I will analyze the film for the most part on its own terms, with some critical discussion of its attention to historical context, rather than within the framework of the Jägerstätter historiography.

[4] Erna Putz, Franz Jägerstätter – Martyrer : Leuchtendes Beispiel in dunkler Zeit (Bischöfliches Ordinariat der Diözese Linz, 2007), 84-85.

[5] Putz, pg. 68.

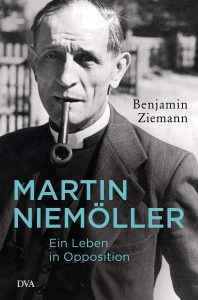

To this day, Martin Niemöller remains one of the most famous German churchmen of the twentieth century. He is regarded as an upright resistance fighter against Hitler, who testified to his stance with seven years of incarceration in concentration camps, as a preacher who admonished German “guilt” and as someone who had transformed from an imperial submarine commander of the First World War into a pacifist, who during the 1950s eloquently and powerfully opposed the Federal Republic of Germany’s Western alliance, its remilitarization, and nuclear weapons. Now, 35 years after Niemöller’s death in 1984, Benjamin Ziemann, Professor of Modern German History at the University of Sheffield and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, cuts through the thicket of legend concerning Niemöller’s story and uncovers important strands of his life.

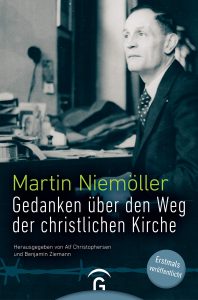

To this day, Martin Niemöller remains one of the most famous German churchmen of the twentieth century. He is regarded as an upright resistance fighter against Hitler, who testified to his stance with seven years of incarceration in concentration camps, as a preacher who admonished German “guilt” and as someone who had transformed from an imperial submarine commander of the First World War into a pacifist, who during the 1950s eloquently and powerfully opposed the Federal Republic of Germany’s Western alliance, its remilitarization, and nuclear weapons. Now, 35 years after Niemöller’s death in 1984, Benjamin Ziemann, Professor of Modern German History at the University of Sheffield and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, cuts through the thicket of legend concerning Niemöller’s story and uncovers important strands of his life. This book, edited by Alf Christophersen and Benjamin Ziemann, has given a surprising moment in Niemöller’s life its most thorough explication. It also offers readers an edited version of the handwritten manuscript Niemöller produced within a period of less than three months during his four years of solitary confinement in Sachsenhausen. His assessment of Catholicism versus Protestantism, a document which numbers over 200 pages in Niemöller’s hand, now comprises 150 printed pages in this book.

This book, edited by Alf Christophersen and Benjamin Ziemann, has given a surprising moment in Niemöller’s life its most thorough explication. It also offers readers an edited version of the handwritten manuscript Niemöller produced within a period of less than three months during his four years of solitary confinement in Sachsenhausen. His assessment of Catholicism versus Protestantism, a document which numbers over 200 pages in Niemöller’s hand, now comprises 150 printed pages in this book. The structure of the book is not unduly distinctive, but it sets out clearly the overall argument and method. Huber’s Bonhoeffer is certainly a big and complex figure. He is also one full of contrasts and the author delights in framing and exploring them. An introductory section evokes the figure of Bonhoeffer as we might first encounter him in a variety of places, not least over the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey. There follows a section on Bonhoeffer’s background and early formation and then another three on his early work in the contexts of university and church life, the first situating him firmly in the landscapes of German thought, the second examining a theology of grace which was deeply rooted in the precepts of Lutheranism, and the third discussing the place of the Bible in a world of maturing historical criticism. Each of these sections present dualities which already defined so much in Bonhoeffer’s work (‘Individual spirituality or Society’; ‘The Church of the World or the Church of the Word’; ‘Acting justly and waiting for God’s own time’; ‘The Historical Jesus or the Jesus of Today’). The young Bonhoeffer is certainly very much at home in the intellectual landscapes of German Lutheranism but the emerging vision is an open one and there is no knowing where it will lead.

The structure of the book is not unduly distinctive, but it sets out clearly the overall argument and method. Huber’s Bonhoeffer is certainly a big and complex figure. He is also one full of contrasts and the author delights in framing and exploring them. An introductory section evokes the figure of Bonhoeffer as we might first encounter him in a variety of places, not least over the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey. There follows a section on Bonhoeffer’s background and early formation and then another three on his early work in the contexts of university and church life, the first situating him firmly in the landscapes of German thought, the second examining a theology of grace which was deeply rooted in the precepts of Lutheranism, and the third discussing the place of the Bible in a world of maturing historical criticism. Each of these sections present dualities which already defined so much in Bonhoeffer’s work (‘Individual spirituality or Society’; ‘The Church of the World or the Church of the Word’; ‘Acting justly and waiting for God’s own time’; ‘The Historical Jesus or the Jesus of Today’). The young Bonhoeffer is certainly very much at home in the intellectual landscapes of German Lutheranism but the emerging vision is an open one and there is no knowing where it will lead. Rebecca Scherf’s study of the German Evangelical Church’s (GEC) responses to the concentration camps is a significant new contribution to the scholarship. While her main focus concerns Protestant clergy who were sent to concentration camps (she confined her study to concentration camps, so it does not include pastors who were in prisons), she has broadened her analysis to address three points of intersection between the GEC and the concentration camp system. The first concerns the relationship between regional churches and the Protestant chaplains who served in the early camps. The second examines the official church responses when clergy were sent to camps. The third looks at the experiences of those who were imprisoned in camps by drawing on contemporary documentation and subsequent memoirs. There are several appendixes with helpful graphs illustrating the number of clergy arrests by year (1935—when there were mass arrests of Confessing pastors due to a pulpit protest—was the peak), by camp, and by regional church. While most clergy who were sent to camps were held only briefly (indicating that the Nazi state intended such arrests as a form of intimidation), the number of arrests during the war grew and fewer were released. There is also a chronologically and geographically organized list of the Protestant clergy who were imprisoned.

Rebecca Scherf’s study of the German Evangelical Church’s (GEC) responses to the concentration camps is a significant new contribution to the scholarship. While her main focus concerns Protestant clergy who were sent to concentration camps (she confined her study to concentration camps, so it does not include pastors who were in prisons), she has broadened her analysis to address three points of intersection between the GEC and the concentration camp system. The first concerns the relationship between regional churches and the Protestant chaplains who served in the early camps. The second examines the official church responses when clergy were sent to camps. The third looks at the experiences of those who were imprisoned in camps by drawing on contemporary documentation and subsequent memoirs. There are several appendixes with helpful graphs illustrating the number of clergy arrests by year (1935—when there were mass arrests of Confessing pastors due to a pulpit protest—was the peak), by camp, and by regional church. While most clergy who were sent to camps were held only briefly (indicating that the Nazi state intended such arrests as a form of intimidation), the number of arrests during the war grew and fewer were released. There is also a chronologically and geographically organized list of the Protestant clergy who were imprisoned. The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration.

The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration.