Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 29, Number 1/2 (Summer 2023)

Review of Andrew Chandler, British Christians and the Third Reich: Church, State, and the Judgement of Nations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022). Pp. x + 422. ISBN: 9781107129047.

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

Andrew Chandler has written an engaging study of the substantial preoccupation and response of diverse British Christians to Nazism, the German “Church Struggle,” the persecution of the Jews, and the Second World War. Chandler has been immersed in this history for over 30 years, and the resulting depth of knowledge shines through in the thoroughness of his research and the perspicacity of his historical judgments.

At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press.

At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press.

As the study of British Christians rather than simply British churches, Chandler’s work explores the way Christians and Christian thinking about Nazi Germany was brought to bear in ecclesiastical, political, and cultural spheres. To that end, he begins with an overview of the way in which British Christianity (Anglican, Catholic, and Free Church) was engaged with both domestic and international political concerns, through a wide variety of institutions, conferences, and (especially) publishing endeavours. Doctrinal concerns, Chandler notes, did not generally stand in the way of interaction and cooperation among the many Christian leaders and intellectuals he analyzes. These include various Anglican prelates (Cosmo Lang, Herbert Hensley Henson, William Temple, Arthur Headlam, George Bell, Arthur Stuart Duncan-Jones) and lay leaders (James Parkes, Sir Wyndham Deedes), Catholic standouts (Cardinal Bourne, Arthur Hinsley, Christopher Dawson, Michael de la Bedoyere), and Free Church notables (Henry Carter, J.H. Rushbrooke, Alfred E. Garvie, Nathaniel Micklem, William Paton, J.H. Oldham, Dorothy (Jebb) Buxton, Bertha Bracey, Corder Catchpool) whom he describes in a series of helpful biographical sketches near the beginning of the book (33-50). These are among the primary figures in Chandler’s study, the ones whose words and deeds stand in for “British Christians” more generally. It could be argued, of course, that these men and women were hardly representative of British Christians as a whole, but as spokespersons for broad swathes of British Christianity, they represent at least the attitudes and ideas in play at the leadership level of the churches—ideas communicated through church hierarchies and denominational networks, as well as through a myriad of church publications.

Chandler frames his history in five eras: during 1933-1934, British Christians first encountered Nazi Germany, developed views about it, and explored potential responses; 1935-1937 was marked by debates about whether to accept or oppose Nazism, in which Christians tended to land on the critical side; 1938-1939 introduced urgent debates about “German expansion and western Appeasement,” new and more violent attacks against Jews in Germany, and the growing likelihood of war; from 1939-1943, Britain led the war effort for democracy and against Nazi-occupied Europe, and Christians grappled with the “themes of collaboration, complicity, and resistance;” and 1943-1949 revolved around conceptual debates about “justice and judgment” and real problems of Allied occupation and humanitarian crises (8-9).

In the first section, on the period of the Nazi seizure and consolidation of power, Chandler argues “it was not true” that international opinion was slow to note and criticize Hitler’s regime (51). Yet there were doubts about whether the Treaty of Versailles would bring a lasting peace and many political attacks against democracy. Within weeks of the Nazi seizure of power, British Christians understood that Nazism was a challenge to the international system, a danger to both its political opponents and German Jews, and a dictatorial threat to German churches. While those like the Quaker Corder Catchpool in Berlin and International Student Services official James Parkes in Geneva served as important sources of information, others like Archbishops Lang of Canterbury and Temple of York consulted with government representatives and British Jewish leaders and launched debates in the House of Lords. Laypeople like Quaker Bertha Bracey established organizations like the Germany Emergency Committee, while churchmen of all stripes wrote protests in the church press.

During the eruption of the German “Church Struggle,” British Christians learned much about the diverse positions of Christians in Germany towards the Nazi state. “What is at once striking,” Chandler notes, “is the strength of the British response to these affairs” (86). The Archbishop of Canterbury’s Council on Foreign Relations was the site of much of the early conversation about the German turmoil, with information supplied by ecumenical figures like Bishop Bell of Chichester. Indeed, Arthur Stuart Duncan-Jones, Dean of the Chichester Cathedral, travelled to Germany and met pro-Nazi “German Christians,” opponents who would eventually form the Confessing Church, and even (surprisingly) Hitler himself. The result was a nuanced view of the situation, but also one that urged caution with respect to intervening in German church affairs (90).

Chandler describes the growing conflict between Bishops Headlam of Gloucester and Bell—the former overly sympathetic to the Hitler regime and prone to antisemitic remarks and the latter (along with Archbishop Lang) increasingly critical of the Nazi regime and its allies in the German Christian Movement. Bell also became quite involved in the emerging Jewish refugee crisis, while Archbishop Temple attempted to intercede with Hitler himself—just one of many interventions by British Christians against the German government. Chandler explains that by the summer of 1934, the German Foreign Office was expressing concern over the effect of German church affairs on international opinion, and British protests against antisemitism were also growing prominent. International Christian gatherings like the 1934 Baptist World Congress and the Life and Work Conference in Fanø were also taken up with the German church situation.

In the section covering 1935-1937, Chandler argues that the growth of a movement favouring rapprochement with Germany should not lead us to undervalue the resistance that remained within liberal democratic society. “British Christians were often found to be an expressive element of this [resistance], and they played a prominent part in maintaining a critical consensus when it might easily have lost its force and subsided” (139). Germany was, after all, still a racial dictatorship. Jews were, afterall, still a persecuted minority there. Christians too were still harassed and persecuted. Concentration camps still threatened, and the refugee crisis continued to grow. Indeed, while the direct interventions of British Christians waned, having grown less successful with the increasing confidence of the National Socialist state, new humanitarian ventures became a means by which British Christians could respond to the crisis in the German church, state, and society.

For instance, Quaker Dorothy Buxton travelled to Germany and spoke out (somewhat controversially) against the concentration camps in which the Hitler regime incarcerated its political opponents. Bishop Bell was reluctant to follow her lead, especially with a new round of conflict in the German “Church Struggle.” Public speeches and letters of protest concerning the treatment of the German churches were offered up by a range of British Christians: former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, Bell, Temple, Bishop Henson of Durham, Moderator of the Federal Council of Free Churches Sidney Berry, and others. All of these protests found their way to Berlin, and Bell also visited Germany, meeting with both political and ecclesiastical leaders. An important moment came in November 1935, when Bell introduced a motion expressing “sympathy ‘with the Jewish people and those of Jewish origin’ in Germany” in the Anglican Church Assembly. When opposition to the motion emerged, Bishop Henson gave an impromptu and explosive address denouncing Nazi Germany, carrying the day (157-159). At the same time, on the ground, Catchpool and other Quakers in Berlin were attempting to aid concentration camp prisoners and protect Jewish institutions under threat.

The year 1936 saw yet more British Christian criticism of Nazi Germany, with a sharpening focus on its pagan and totalitarian nature. Alongside these continuing protests, there were new examples of concrete action, such as the creation of the International Christian Committee for Refugees, chaired by Bell and supported by Lang in an effort to aid so-called non-Aryan Christians (not least, children) in need of new homes outside of Germany. But the reports of British Christians visiting Germany were mixed. A.J. Macdonald of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Council on Foreign Relations played down the situation, arguing that German pastors just wanted to get on with their work and that only those who opposed the state politically landed themselves in trouble. Bell found the situation much more serious, though his German church contacts were pessimistic about and even reticent of foreign intervention. And the Congregationalist Principal of Mansfield College (Oxford), Nathaniel Micklem, discovered an underground German church fearful of arrest by secret police. In 1937, attention shifted to Roman Catholic opposition to Nazism with the publication of Pope Pius XI’s Mit brennender Sorge (“With Burning Concern”) encyclical. British Catholics were well aware of how much relations between Germany and the Catholic Church had deteriorated. Meanwhile, Anglican and Quaker attempts to raise money for non-Aryan Christian refugees fared poorly and the ongoing argument between Bishops Headlam and Bell over the church’s stance towards Germany only muddied the waters. But the arrest and incarceration of Confessing Church leader Martin Niemöller sparked a new round of British Christian protests in late 1937 (195-195).

Concerning the build-up to the Second World War, Chandler asks how the morality of the appeasement policy and the presence of a significant pacifist minority coexisted with the ever-growing refugee crisis and the public scandal concerning Pastor Niemöller, “the most famous political prisoner in the world” (204). On the one hand, Chandler notes,

Appeasement sought to avoid another Great War and this resolve possessed the authority of a national consensus. In March 1938 the Church Times pronounced, ‘Is it not the law of God to try friendship and understanding?’ From the spring of 1938 the policy of the Chamberlain government found the winds of Christian opinion blowing supportively in its sails. (208)

On the other hand, criticisms such as Duncan-Jones’ The Struggle for Religious Freedom in Germany described the religious mysticism of Nazi Germany as “fundamentally irreconcilable” with Christianity and lambasted the oppression and “cruelty of Moloch” (205-206). Buxton, Bell, Lang, Micklem, and others continued to protest Niemöller’s incarceration, while the refugee crisis grew ever worse with the annexation of Austria. Bell, in particular, understood that political events were overshadowing the “Church Struggle” and that British Christian intervention no longer had any effect whatsoever in Germany (218-219).

But if the Munich Agreement had been greeted with calls for a national day of thanksgiving (Lang) and if Te Deums rang out in Catholic churches, the Kristallnacht Pogrom of November 1938 brought all that to a halt, shocking British Christians and shattering hopes for peace. Archbishop Lang published an indignant letter (“A Black Day for Germany”) which was later affirmed by the Church Assembly. The Catholic Herald described Nazi “sub-human behaviour” while the Baptist Times argued, “The time for silence is past.” As the Munich consensus disintegrated, British Christians invested new energy into refugee work, which was boosted by the government decision to allow child refugees to enter Britain. Sponsorships abounded. Church statements grew firmer, too. In a March 1939 House of Lords speech, Lang urged “the massing of might on the side of right,” and when Hitler launched the war in September, he announced in the same chamber that, “I shrink indeed from linking our broken lights and our fallible purposes with the Holy Name of God, yet I honestly believe that in this struggle, if it is forced upon us, we may humbly and trustfully commend our cause to God” (260, 269).

Chandler devotes no less than 100 pages to the period of the Second World War. In the main, he notes how, with London as the international capital of a war-torn continent, British Christians engaged in new patterns of association and collaboration, not least between Protestants and Catholics and between Christians and Jews. Through these, Christians responded to the moral challenge of National Socialist ideology and politics. In the main, the European conflict was justified by Christian leaders of all kinds as a “righteous war” (273). Hitler and Nazism were condemned as evil, even as church leaders expressed sympathy for the German people, whom they regarded as deceived and led astray. Many German exiles came to London, where they collaborated with German and British Christians on publications and radio broadcasts. Though relations with the German churches were effectively severed by the war, fragments of news painted a bleak picture. The moral stance of most leading British Christians discouraged the idea of a negotiated peace, though the Vatican was working diplomatic channels intensely and ecumenical representatives in Geneva kept their hopes alive.

Among Catholics, Cardinal Hinsley, Archbishop of Westminster, rose to prominence as a supporter of the war. At a 1940 National Day of Prayer Mass broadcast by the BBC, he declared, “Can any Christian now hear with indifference that clarion call to defend the right; to protect the souls of millions of our brethren cruelly assailed and oppressed?” The war, he continued, was a “just crusade for the deliverance from evil which rests its strength on force alone” (287). Similar rhetoric abounded across the Christian spectrum, as the war gave rise to a vast literature on politics, religion, and morality, including Bell’s Christianity and World Order, published by Penguin (296). And debates broke out, like the one between those who regarded Germans as possessing an essentially Nazi national character and thus collectively guilty, such as senior British diplomat Sir Robert Vansittart, and those who believed there were good Germans who could be cultivated and supported in the fight against Hitler, like Bell.

New relationships—particularly among laypeople—brought Protestants and Catholics closer together in a common cause, captured in historian Christopher Dawson’s call for “‘a return to Christian unity’ in the name of civilisation” (301). Similarly, the Council of Christians and Jews was established in 1942 “to co-operate in the struggle against religious and racial persecution” (310). When the British government was slow to distinguish the mass murder of Jews as a special crime in the fall of 1942, Archbishop Temple and Viscount Cecil (Free Churches) led a protest at Royal Albert Hall. That December, the Council of Christians and Jews took up a paper entitled, “Discussion of Present Extermination Policy of Nazi Government in Respect of European Jewry” (322). Various condemnatory statements were publicized by Christian leaders, but as they learned ever more about the annihilation of the Jews over the course of 1943, Temple and others expressed concern that the government’s response was far too timid. Repeated attempts to influence official policy were largely fruitless (343-349).

As the war progressed and Allied victory could be imagined, British Christians raised questions about the morality of war, the nature of a just peace, and the Christian principals that might inform a new postwar order. A Peace Aims group, spearheaded by the Presbyterian William Paton, worked to outline the Christian moral basis for peace and the political reconstruction of Europe. Striking the balance between justice and vengeance proved to be a key challenge. Any hopes that Christian leaders might shape the international settlement of the conflict were dashed by mid-1944. Much to their chagrin, retribution had emerged as the British aim with respect to Germany, and the fire-bombing of German cities illustrated the extent to which “total war” had taken hold (355-361).

After the defeat of Germany, even as the International Military Tribunal prepared to try representative German war criminals, British Christians like Bishop Bell and Wesleyan Methodist Henry Carter began the task of organizing humanitarian relief. A “Save Europe Now” campaign was launched. A new organization, Christian Reconstruction in Europe, was formed and was soon folded into the British Council of Churches as the Department of Interchurch Aid and Refugee Service. Additionally, Carter chaired the new World Council of Churches’ Ecumenical Refugee Commission. Meanwhile, Bishop Bell and Methodist Gordon Rupp met with other ecumenical representatives of the World Council of Churches in the Process of Formation in Stuttgart in October 1945, making contact with the emergence Evangelical Church in Germany. It was here that Martin Niemöller and Otto Dibelius drafted the famous Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt. Despite its shortcomings, it opened the door for the German churches to re-enter the ecumenical realm. As for the Nuremberg Trials, Chandler details the controversial opposition of Bishop Bell, who sought to limit the extent of this judicial process (379-387).

A short “Endings and Legacies” chapter offers brief summaries of the postwar careers of some of the main characters in Chandler’s study, many of whom he regards—probably rightly—as underappreciated. In an interesting discussion of the place of German theology in postwar Britain, Chandler explains the rise of Christian writing about the German “Church Struggle,” German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and the biographies of Confessing Church leaders. He also explains the rise of new points of contact between the Christian denominations and also between Christians and Jews. Finally, he demonstrates how leading British scholars of the history and theology of the German churches under Nazism had personal links to important British Christians of that era.

In sum, Andrew Chandler’s British Christians and the Third Reich: Church, State, and the Judgement of Nations is a thoroughly researched and fascinating exploration of the moral and political engagement of leading Anglican, Catholic, and Free Church figures in Nazism, the German “Church Struggle,” the persecution of the Jews, and the Second World War. It is rich with detail from primary sources, which nicely communicates both the spirit and depth of British Christian engagement in the moral questions of the era. In true transnational historical form, it enhances our understanding of both British and German church politics during the Nazi era, along with the surprising extent to which communications flowed between the two sets of political and ecclesiastical elites.

Christian internationalism has yet to find a secure place in the various histories of twentieth-century churches. Very largely this is due to a persistent emphasis on national categories and narratives, but denominational perspectives have also fashioned a great deal of what we expect to find in the foreground. All too often, Bell and Oldham may be observed, usually dutifully and briefly, hovering in the background of anything other than ecumenical surveys. In the final volume of the recent Oxford History of Anglicanism (OUP, 2019), Bell flits about here and there, but there is no very confident sense of where to put him for very long. Meanwhile, Oldham, the United Free Church layman, has almost vanished from ecclesiastical memory altogether. This is an authentic tragedy because it indicates how horizons have contracted across the western Protestant churches in the half-century since their deaths.

Christian internationalism has yet to find a secure place in the various histories of twentieth-century churches. Very largely this is due to a persistent emphasis on national categories and narratives, but denominational perspectives have also fashioned a great deal of what we expect to find in the foreground. All too often, Bell and Oldham may be observed, usually dutifully and briefly, hovering in the background of anything other than ecumenical surveys. In the final volume of the recent Oxford History of Anglicanism (OUP, 2019), Bell flits about here and there, but there is no very confident sense of where to put him for very long. Meanwhile, Oldham, the United Free Church layman, has almost vanished from ecclesiastical memory altogether. This is an authentic tragedy because it indicates how horizons have contracted across the western Protestant churches in the half-century since their deaths.

At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press.

At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press. The structure of the book is not unduly distinctive, but it sets out clearly the overall argument and method. Huber’s Bonhoeffer is certainly a big and complex figure. He is also one full of contrasts and the author delights in framing and exploring them. An introductory section evokes the figure of Bonhoeffer as we might first encounter him in a variety of places, not least over the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey. There follows a section on Bonhoeffer’s background and early formation and then another three on his early work in the contexts of university and church life, the first situating him firmly in the landscapes of German thought, the second examining a theology of grace which was deeply rooted in the precepts of Lutheranism, and the third discussing the place of the Bible in a world of maturing historical criticism. Each of these sections present dualities which already defined so much in Bonhoeffer’s work (‘Individual spirituality or Society’; ‘The Church of the World or the Church of the Word’; ‘Acting justly and waiting for God’s own time’; ‘The Historical Jesus or the Jesus of Today’). The young Bonhoeffer is certainly very much at home in the intellectual landscapes of German Lutheranism but the emerging vision is an open one and there is no knowing where it will lead.

The structure of the book is not unduly distinctive, but it sets out clearly the overall argument and method. Huber’s Bonhoeffer is certainly a big and complex figure. He is also one full of contrasts and the author delights in framing and exploring them. An introductory section evokes the figure of Bonhoeffer as we might first encounter him in a variety of places, not least over the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey. There follows a section on Bonhoeffer’s background and early formation and then another three on his early work in the contexts of university and church life, the first situating him firmly in the landscapes of German thought, the second examining a theology of grace which was deeply rooted in the precepts of Lutheranism, and the third discussing the place of the Bible in a world of maturing historical criticism. Each of these sections present dualities which already defined so much in Bonhoeffer’s work (‘Individual spirituality or Society’; ‘The Church of the World or the Church of the Word’; ‘Acting justly and waiting for God’s own time’; ‘The Historical Jesus or the Jesus of Today’). The young Bonhoeffer is certainly very much at home in the intellectual landscapes of German Lutheranism but the emerging vision is an open one and there is no knowing where it will lead. The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration.

The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration. The suppression of the Bruderhof in Nazi Germany was not unobserved in Britain: there were protests and interventions by figures as diverse as the eminent Anglican laymen Sir Wyndham Deedes and the Baptist internationalist J.H. Rushbrooke. Friends of all kinds now proved effective, particularly in practicalities. By May 1936, the Bruderhof could be found in a farm near Ashton Keynes in the Cotswolds where a new community comprised sixteen Germans, fourteen British friends, and one Austrian. At the height of its quiet prosperity there, in October 1939, the community included as many as 119 Germans, 116 British members, 30 Swiss, 17 Austrians, and stray individuals from the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, France, Sweden, Italy, and Turkey. All came with their own stories and for their own reasons. All sought to be useful. A miner from the coalfields of Durham cycled three hundred miles to join them and was promptly set to work picking potatoes; another new arrival was a Lancashire poultry farmer who was also a Methodist lay preacher and admirer of the Indian Christian mystic Sundar Singh. In choosing the Cotswolds, a deeply rural area which possessed something of the character of an English arcadia, the community chose well. Birmingham, the second city of the country and a bastion of Quakerism and Free church life and worship, was not far away. Ashton Keynes also had a railway station. Visitors and longer-term guests could come and go as they chose – and they did.

The suppression of the Bruderhof in Nazi Germany was not unobserved in Britain: there were protests and interventions by figures as diverse as the eminent Anglican laymen Sir Wyndham Deedes and the Baptist internationalist J.H. Rushbrooke. Friends of all kinds now proved effective, particularly in practicalities. By May 1936, the Bruderhof could be found in a farm near Ashton Keynes in the Cotswolds where a new community comprised sixteen Germans, fourteen British friends, and one Austrian. At the height of its quiet prosperity there, in October 1939, the community included as many as 119 Germans, 116 British members, 30 Swiss, 17 Austrians, and stray individuals from the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, France, Sweden, Italy, and Turkey. All came with their own stories and for their own reasons. All sought to be useful. A miner from the coalfields of Durham cycled three hundred miles to join them and was promptly set to work picking potatoes; another new arrival was a Lancashire poultry farmer who was also a Methodist lay preacher and admirer of the Indian Christian mystic Sundar Singh. In choosing the Cotswolds, a deeply rural area which possessed something of the character of an English arcadia, the community chose well. Birmingham, the second city of the country and a bastion of Quakerism and Free church life and worship, was not far away. Ashton Keynes also had a railway station. Visitors and longer-term guests could come and go as they chose – and they did. This sense of observing and interpreting like a guest whose eyes are being opened by degrees to something new and unexpected is certainly one of the strengths of the book. It makes Newell himself something of a tourist – in the best sense – and equally an attractive introducer to readers coming to the same questions afresh. The vital presence at the heart of the story is the pastor of the Nikolaikirche himself, Christian Führer, who in 1989 opened the doors of the church to all people – and, in particular, to many who were disaffected by the Communist state – so that they could meet together, light candles, share what was important to them all and find new ways to insist upon these things in a world of repression and intimidation.

This sense of observing and interpreting like a guest whose eyes are being opened by degrees to something new and unexpected is certainly one of the strengths of the book. It makes Newell himself something of a tourist – in the best sense – and equally an attractive introducer to readers coming to the same questions afresh. The vital presence at the heart of the story is the pastor of the Nikolaikirche himself, Christian Führer, who in 1989 opened the doors of the church to all people – and, in particular, to many who were disaffected by the Communist state – so that they could meet together, light candles, share what was important to them all and find new ways to insist upon these things in a world of repression and intimidation. Studdert Kennedy, or ‘Woodbine Willie’, as he was affectionately known by soldiers, has long been the most well-known of the British wartime chaplains. He has attracted the attention of scholars of various kinds for his poetry (The Unutterable Beauty, published in 1927, remains much admired in some quarters), his trenchant criticisms of the status quo, his uncompromising socialism, his pungent scepticism of authority (one of his books was simply called Lies), and his determination that the ghastliness of war must surely and eventually yield a better world. But he was also the embodiment of courage and unselfconscious sacrifice (he won the Military Cross) and his early death, exhausted, at the age of 45, presented something of the quality of a martyrdom—not so much to the powers of the age but perhaps to the whole age in which he lived. Westminster Abbey notoriously turned down the idea of hosting his funeral. One suspects that Studdert Kennedy would have been delighted by the compliment.

Studdert Kennedy, or ‘Woodbine Willie’, as he was affectionately known by soldiers, has long been the most well-known of the British wartime chaplains. He has attracted the attention of scholars of various kinds for his poetry (The Unutterable Beauty, published in 1927, remains much admired in some quarters), his trenchant criticisms of the status quo, his uncompromising socialism, his pungent scepticism of authority (one of his books was simply called Lies), and his determination that the ghastliness of war must surely and eventually yield a better world. But he was also the embodiment of courage and unselfconscious sacrifice (he won the Military Cross) and his early death, exhausted, at the age of 45, presented something of the quality of a martyrdom—not so much to the powers of the age but perhaps to the whole age in which he lived. Westminster Abbey notoriously turned down the idea of hosting his funeral. One suspects that Studdert Kennedy would have been delighted by the compliment. George Bell was born in 1883 on the south coast of England, into a “secure, comfortable middle-class clerical home” (7). He attended Westminster School beginning in 1896, then Christ Church, Oxford, in 1901. Next he enrolled in theological college in Wells, in the West of England, where he was introduced to the student ecumenical movement and to Christian Socialism. Ordained as a deacon in Ripon Cathedral in 1907 and as a priest in Leeds in 1908, Bell returned to Oxford in 1910, where he combined a growing commitment to social justice with a vibrant personal faith. As he explained, “Christianity is a life before it is a system and to lay too much stress on the system destroys the life” (12).

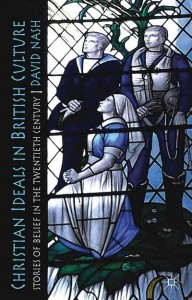

George Bell was born in 1883 on the south coast of England, into a “secure, comfortable middle-class clerical home” (7). He attended Westminster School beginning in 1896, then Christ Church, Oxford, in 1901. Next he enrolled in theological college in Wells, in the West of England, where he was introduced to the student ecumenical movement and to Christian Socialism. Ordained as a deacon in Ripon Cathedral in 1907 and as a priest in Leeds in 1908, Bell returned to Oxford in 1910, where he combined a growing commitment to social justice with a vibrant personal faith. As he explained, “Christianity is a life before it is a system and to lay too much stress on the system destroys the life” (12). The cover announces the character of the theme: it is the image of a stained glass window in Worcester Cathedral showing three resolute figures looking up towards the sky, intent, devout, broadly sanguine. One is a nurse and the other two are men of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. The task that David Nash has set himself here is a striking one: in what kinds of narratives might the historian find the relationship between religious faith and active public life in the British twentieth century? How are we to locate the dimension of personal faith in the discussions and dramas of society at large? How are we to know when it is there – or when it is not?

The cover announces the character of the theme: it is the image of a stained glass window in Worcester Cathedral showing three resolute figures looking up towards the sky, intent, devout, broadly sanguine. One is a nurse and the other two are men of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. The task that David Nash has set himself here is a striking one: in what kinds of narratives might the historian find the relationship between religious faith and active public life in the British twentieth century? How are we to locate the dimension of personal faith in the discussions and dramas of society at large? How are we to know when it is there – or when it is not?