Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 23, Number 3 (September 2017)

John S. Conway: engaged skeptic and skeptical activist

By Doris L. Bergen, University of Toronto

This article was originally published in Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte 27 no. 1 (2014), and is reprinted here with the kind permission of that journal. It had its origins as a presentation at the July 2013 “Reassessing Contemporary Church History” Conference held at the University of British Columbia, where members of the CCHQ editorial team and others also took the opportunity to pay tribute to John S. Conway, founder of CCHQ, on the occasion of his 85th birthday.

John Conway is an intellectual leader, an astute and indefatigable historian of the churches, and a trailblazer in the fields of modern German, modern European and international church history. As everyone who knows John is aware, he is also a generous mentor and loyal friend.[1] John Conway has a sharp sense of humour, and it would be fitting to open this essay with a joke or witticism. But the field in which we work does not easily lend itself to jokes, so I will offer only one illustration of Professor Conway’s sometimes irreverent and always unsentimental approach to life and to himself. A few years ago he told me over the telephone about a serious medical procedure he had just undergone. Rather than highlight the severity of the operation or draw attention to his own discomfort, he exclaimed, “They slit my throat!”

As an expert on the churches in National Socialist Germany, Conway has been interviewed for several documentaries. He appears in a widely circulated film entitled Stand Firm: Jehovah’s Witnesses Stand Firm Against Nazi Assault [2], and he also features in Martin Doblmeier’s award-winning 2003 film, Bonhoeffer.[3] These media appearances encapsulate several important qualities of Conway’s work and life and illustrate in a compelling way who he is. Although separated by seventeen years they show some striking similarities. In both interviews Conway emphasizes the importance of the First World War in shaping subsequent events. He also speaks in similar ways about Adolf Hitler and the churches, in both films displaying a combination of distance and proximity, a balance between scholarly detachment and moral engagement that characterizes all of his work. Also notable is Conway’s treatment of antisemitism, where in both cases he moves from a scholarly analysis of the past to a call for action and activism in the present.

The First World War

The importance of the First World War is evident throughout all of John Conway’s work. In his publications, in the books he has chosen to review over the years and in the many academic and public talks he has given, the theme of the war and its dreadful impact on European culture and society and on Christianity around the world recurs over and over again.[4] It was during the First World War, Conway insists, when church leaders on all sides of the conflict preached the jingoist credo of “Gott mit uns!” – “God is on our side!” – that the Christian churches sowed the seeds for the decay of their credibility throughout the twentieth century.[5]

But Conway communicates an even bigger point about the war. The core problem he engages is the violence of the world, the destruction that human beings wreak on one another. Religion has a particular place in this set of issues. As Conway sees it, the role of Christianity and of the churches as moral authorities creates a responsibility to guide people toward what is good and right, but instead during the First World War church leaders egged on the brutality. Rather than healing and strengthening the best potential in people, they were blinded and obstructed the moral vision of their members and followers. They misused their authority and in the process forfeited it. Conway’s anguish at the suffering the war unleashed on the world and the failure of the Christian churches in the face of it is palpable in everything he does. The problem as Conway conceptualizes it is as old as the church and worldwide, and as a result his work, though concentrated on Germany (and the two Germanys)[6], always has a global perspective.

Many details of Conway’s biography connect with this preoccupation with the First World War and the problems of violence and suffering. John Conway was a student at Cambridge University. He started off studying literature, a decision that followed in the footsteps of many famous scholars in his family. His grandfather, R. S. Conway (Robert Seymour Conway, 1863-1933), was a well-known classicist, famed, among other accomplishments, for the vicious reviews he wrote. (The many of us who have had our books reviewed by John over the years can be grateful that he did not inherit this characteristic).

John Conway switched to History apparently because he had a sense that it might be better able to provide tools to respond to the recent past, the Second World War (an opinion in which he differs from his daughter Alison Conway, a professor of literature in Canada).[7] The young John Conway did his compulsory military service in the postwar period when that cataclysmic conflict was still a raw wound. His father, also a Cambridge man, served as captain of the English rugby team and in the trenches during the First World War. It is not surprising that John Conway has an enduring interest in religion and war, including specifically in military chaplains, in all their contexts. For his work Germany has always been a major case to study[8], but the world as a whole is his real stage.

In 1955 Conway faced a major culture shock when he left Cambridge for his first academic position, at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada. He had to return to England to submit and defend his dissertation, and on the boat back he met his future wife, Ann. Evidently Ann had embarked on her own Commonwealth adventure, with plans to go from Canada to India, Australia and other faraway destinations. Instead she married John, which brought other kinds of adventures, though they did include travel. The two of them and their children have always moved internationally: their son David divides his time between Mexico and Canada, and from there he works designing film sets for Hollywood.

John Conway has always been on the move. He was offered his next academic position, at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, on a train, and one of his gifts to that institution was a travel scholarship for graduate students to go to Germany and Israel. (Historian Steven Schroeder was one of the recipients of this award).[9] Perhaps the most lasting evidence of Conway’s international scope is the newsletter he founded to connect people around the world with an interest in contemporary church history. Several decades and at least two changes in title later, it has thousands of subscribers spread across all continents.[10]

Distance and Moral Engagement

Conway’s most famous work, his book, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches[11], received considerable praise for its depth of research and clarity of judgment. But it was also criticized by reviewers, some of whom deemed it too harsh, others of whom accused Conway of being too forgiving of the Germans. This divided response brings to mind Isaiah Berlin’s essay on Ivan Turgenev, the author of Fathers and Sons. Turgenev, Berlin maintained, proved himself to be a genuine moderate and a true liberal because he was attacked from both sides.[12] In Conway’s case, that two-pronged attack offers evidence that he is a genuine scholar whose work combines the proximity of profound engagement with the distance of objectivity or better put, restrained subjectivity.[13]

For Conway the goal is to capture the big picture. His is a perspective that focuses on structures and forces larger than individual manipulation, akin to the Annales view of history. Yet he insists on individual responsibility at the same time, and his statements in this direction are all the more powerful for their sparseness. Conway’s friendships are legendary, and his strong ties to Rudolf Vrba, a survivor and escapee from Auschwitz[14], and to Eberhard Bethge, Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s friend and biographer, are at the heart of some of his most moving work. Likewise the longstanding bond with Franklin Littell produced extraordinary results, including the Scholars Conference on the Holocaust and the Church Struggle, a major international venue for presentation of research and the stimulus for a series of important volumes.

Conway’s trademark balance of engagement and distance also reflects aspects of his biography. His mother, Dr. Elsie Conway, was an academic too, a marine botanist, to be precise, with a degree from the University of Glasgow. As a boy, John Conway joined his two brothers in collecting seaweed for their mother to analyze. So of course it has been natural for Conway throughout his career to share the stage with women academics and to mentor women as well as men. His daughter, Jane Lister, is a Dean at Okanagan College in Vernon, Canada. Conway’s interpretations of the past reveal his conviction that history in the end is a gloomy science where big forces are at play. In place of the false pride of the idealist, Conway has the cold eye of a realist. Hence his admiration for William Rubinstein’s iconoclastic book, The Myth of Rescue: Why the democracies could not have saved more Jews from the Nazis.[15] Rubinstein set out to counter the notion that no one “did anything” to help Jews by pointing out that indeed there was a severe limit to what the United States, Britain, and Jews around the world could have done.

Conway has made a similar argument about the Vatican, not to absolve Pius XII of responsibility or to endorse wildly exaggerated claims of papal rescue efforts, but to introduce a reality check into the conversation. His extensive response to Rolf Hochhuth’s play, The Deputy, published in 1965 [16], is still cited, though sometimes by ardent defenders of the papacy who read it selectively. John Conway is neither an apologist nor a fatalist. For him distance opens space for genuine engagement with the past rather than for judgment. His position is always complex, and although he insists that there is a limit to what could have been done, he is equally clear that much more should have been done by the Vatican, the Allies and Christians inside Germany and all over the world to aid Jews and to stand by them.[17]

Conway’s scholarship always shows his feet on the ground, critically engaging with complex issues. His 1989 essay on Canada and the Holocaust is a case in point: it manages to avoid both the familiar congratulatory stance (Canada the multicultural haven) and the lugubrious ‘we did nothing’ to provide a clear-sighted account that is all the more damning for its understated tone.[18] Never one to take the easy route, Conway also tackled the thorny issue of the Jewish leaders in Hungary and charges that they suppressed the 1944 Vrba-Wetzler report and thereby blocked the possibility of more people managing to evade the Nazi killing machine.[19] In 2006 Yehuda Bauer devoted a lengthy piece in the Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte to refuting Conway on this point.[20] As Conway’s students at the University of British Columbia could attest, it was always his goal to provide evidence and then let them make up their own minds as to what they thought.

Activism

In Stand Firm, there is a segment where Conway describes the churches’ reaction to Kristallnacht: “So when the ‘Crystal Night’ pogrom takes place in November 1938, that shocking and very visible evidence of Nazi antisemitism, the churches were totally silent.”[21] He bites off the word ‘silent’ with a finality that speaks volumes, and the director or editor had the dramatic sense to end the scene there. Conway himself has been far from silent throughout his career, and although his words have spoken loudly, his actions speak even louder. While searching for some of Conway’s early articles I stumbled across a 1977 publication entitled Visit to the Tibetan Settlements in Northern India.[22] This must have been written by a different John Conway, I assumed, knowing that both “John” and “Conway” are common names in the Anglo-American context. But something made me check to be sure, and indeed, this fascinating report was the work of Professor Conway in his role as Vice Chair of the Tibetan Refugee Aid Society of Canada.

In that capacity Conway made a series of trips to India, during which he met the Dalai Lama and supervised the progress of a series of projects he and his organization had initiated and continued to support. In painstaking detail he described visits to schools, monasteries, and elder care facilities. He also wrote knowledgeably about tractors and toilets and movingly about the people he encountered. This work with Tibetan refugees was part of Conway’s wider involvement with refugee issues, including a major commitment with the people known at the time as ‘boat people’. Alison Conway told me that many times people arrived in Canada with only one telephone number: John Conway’s. In this enterprise Conway worked closely with the well-known anarchist George Woodcock, who moved from England to British Columbia after the Second World War.[23] They did not see eye-to-eye on every political issue but they proved to be a highly effective team in support of people in need.

Conway’s activism is also linked in myriad ways to his family. His wife Ann, a physiotherapist, has always been literally ‘hands-on’ in her attitude toward others. Deeply involved in her church, she is active in promoting First Nations rights in Canada. In the 1970s, she, her husband, and their children welcomed a Tibetan foster child into their home. The child had cerebral palsy and needed a lot of care and attention. The Conways provided a home until the birth parents were able to do so. Like her parents, the eldest daughter, Jane Lister, is very community oriented and initiated a microloans program to help people in the city of Vernon get on their feet. She is also an expert in corporate social responsibility and global environmental governance.[24] Conway’s great-aunt Katharine (Kitty) Conway (later Glasier) was one of the founders of the Independent Labour Party of England.[25] Known for her position of ethical socialism, she too was a classicist by training. Perhaps that long view gave her and gives her great-nephew a sense of the magnitude of human suffering and the massive forces that generate it. For both of them that awareness comes coupled with a powerful drive to do what you can to alleviate suffering.

Reflecting on these themes and John Conway’s treatment of them through his scholarship and activism brings to mind a well-known passage in Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov, from the part of the book known as ‘The Grand Inquisitor.’ Two brothers, Ivan and Alyosha, dispute the meaning of human suffering and the appropriate response. Ivan, the nihilist, skeptic, and genius of reason, rants in despair. Armed with a seemingly endless list of horrific cases of brutal treatment of children that he has found in the newspapers, he delivers a brilliant argument against the existence of God, or at least of a loving, benevolent God who cares about human beings. Alyosha, the monk, remains silent until his brother has ended his diatribe. Then he does two things: he kisses his brother and mutters, “Never mind. I want to suffer too.” Mikhail Bakhtin famously characterized Dostoevsky’s approach as ‘polyphonic’, where the interaction, even clash of multiple opposing opinions generates its own truth.[26] John Conway embodies this kind of dialogue, between clearheaded, skeptical, painful reason with no illusions, and solidarity and activism, not always fully articulated or even able to be put into words, but like Alyosha’s response, full of love. We are grateful to John Conway for his example of engaged skepticism and the quiet model he has provided of skeptical activism.

[1] I would like to thank Steven Schroeder, Mark Ruff, Lauren Faulkner Rossi, and Kyle Jantzen for all they did to organize and host the conference on Reassessing Contemporary Church History in July 2013 at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Robert Ericksen was instrumental in bringing some of the important research presented there to the pages of this journal. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Alison Conway, John Conway’s daughter and a professor at Western University in London, Canada for her generous and indispensable assistance.

[2] Jehovah’s Witnesses Stand Firm Against Nazi Assault, Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, New York 1996.

[3] Martin Doblmeier, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Pacifist, Nazi Resister, 2003: winner of the 2004 Religion Communicators Council’s Wilbur Award for best documentary film.

[4] John S. Conway, Bourgeois German Pacifism during the First World War, in: Andrew Bonnell et al. (eds.), Power, Conscience and Opposition: Essays in German History in Honour of John A. Moses, New York 1996.

[5] See also Julien Benda, The Treason of the Intellectuals, translated by Richard Aldington, New York 1969, original publication 1928.

[6] John S. Conway, The Political Role of German Protestantism, 1870-1990, in: Journal of Church and State 34, no. 4 (1992): 819-842; Conway, The ‘Stasi’ and the churches: Between Coercion and Compromise in East German Protestantism, 1949-1989, in: Journal of Church and State 36, no. 4 (1994): 725-745.

[7] Major publications are Alison Conway, The Protestant Whore: Courtesan Narratives and Religious Controversy in England, 1680-1750, Toronto 2010; Alison Conway, Private Interests: Women, Portraiture, and the Visual Culture of the English Novel, 1709-1791, Toronto 2001.

[8] John S. Conway, Coming to Terms with the Past: Interpreting the German Church Struggles, in: German History 16, no. 3 (1998): 377-96.

[9] Steven Schroeder, To Forget It All and Begin Anew: Reconciliation in Occupied Germany 1944-1954, Toronto 2013.

[10] Since Dec. 2012 Contemporary Church History Quarterly, online.

[11] John S. Conway, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches, New York 1968.

[12] Isaiah Berlin, Fathers and Children: Turgenev and the Liberal Predicament, Romanes Lecture, Oxford 1972; reprinted as Introduction to Ivan Turgenev, Fathers and Sons, translated by Rosemary Edmonds, Harmondsworth 1975.

[13] Saul Friedländer put it this way: “My own work, begun in 1990, was meant to show that no distinction was warranted among historians of various backgrounds in their professional approach to the Third Reich, that all historians dealing with this theme had to be aware of their unavoidably subjective approach, and that all could muster enough self-critical insight to restrain this subjectivity.” Saul Friedländer, “Prologue,” in: Lessons and Legacies IX, Jonathan Petropoulos et al (eds.), Evanston, IL 2010: 3.

[14] See a series of publications on Vrba: John S. Conway, Frühe Augenzeugenberichte aus Auschwitz: Glaubwürdigkeit und Wirkungsgeschichte, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 27, no. 2 (April 1979): 260-84. Here Conway discusses the Vrba-Wetzler Report at length in an essay framed by remarks on two then-recent efforts to discredit the Holocaust, by David Irving and Arthur Butz. Also Conway, Der Holocaust in Ungarn. Neue Kontroversen und Überlegungen, in: VfZ (1984): 179-212; and for later reflections and reactions, Conway, Flucht aus Auschwitz: Sechzig Jahre danach, in: VfZ 53, no. 4 (2005): 461-475.

[15] William Rubinstein, The Myth of Rescue: Why the Democracies Could Not Have Saved More Jews from the Nazis, New York 1997.

[16] John S. Conway, The Silence of Pope Pius XII, Review of Politics 27, no. 1 (Jan. 1965): 105-131. Also see John S. Conway, Records and Documents of the Holy See Relating to the Second World War, in: Yad Vashem Studies 15 (1983): 327-45.

[17] John Conway, Between Apprehension and Indifference: Allied Attitudes to the Destruction of Hungarian Jewry, in: Wiener Library Bulletin (1973/4): 37-48.

[18] John S. Conway, Canada and the Holocaust, in: Remembering for the Future: Working Papers and Addenda. Vol. 1: Jews and Christians during and after the Holocaust, Yehuda Bauer et al (eds.), Oxford 1989: 296-305.

[19] See translation of the 1944 Vrba-Wetzler Report as: Testimony of Two Escapees from the Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Camps at Oswiecim, Poland, in: http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/sub_document.cfm?document_id=1535 (accessed Jan. 2014). See also Rudolf Vrba, I Cannot Forgive, London 1963, and Alfred Wetzler, Escape from Hell, New York 2007; originally published in 1963. For analysis see Ruth Linn, Escaping Auschwitz: A Culture of Forgetting, Ithaca, NY 2004.

[20] Yehuda Bauer, Rudolf Vrba und die Auschwitz Protokolle. A reply to John S. Conway, in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 54, no. 4 (2006): 701-710.

[21] Conway quoted in Jehovah’s Witnesses Stand Firm Against Nazi Assault: Study Guide for the Documentary Video, New York 1997: 52.

[22] John S. Conway, Visit to Tibetan Settlements in Northern India, International Project Booklet no. 7, New Westminster, B.C. 1977.

[23] George Woodcock, Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, Toronto 2004; originally published 1962.

[24] Publications include Peter Dauvergne and Jane Lister, Eco-Business: A Big-Brand Takeover of Sustainability, Cambridge, MA 2013; and Dauvergne and Lister, Timber, Cambridge, U. K. 2011.

[25] Paul Salveson, “ILP@120: Katharine Bruce Glasier – The ILP’s Spiritual Socialist,” ILP, Independent Labour Publications (25 Nov. 2013), http://www.independentlabour.org.uk/main/2013/11/25/ilp120-katharine-bruce-glasier-%E2%80%93-the-ilp%E2%80%99s-spiritual-socialist/ (accessed 15 Jan. 2014).

[26] Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, trans. R. W. Rotsel, Ann Arbor, MI 1973.

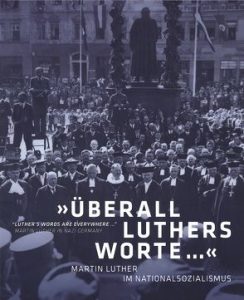

The volume is a product of the conference “The Reception of Luther’s ‘Judenschriften’ in the 19th and 20th Centuries,” which was held at Erlangen University in October 2014. The contributors, who number more than a dozen, represent fields that include Protestant church history, Protestant systematic theology, religion, Jewish studies, and Catholic theology. As the book’s title suggests, the collection of essays covers a broad chronological range; the thematic terrain is wide as well. This breadth is one of the volume’s greatest strengths. The essays addressing nineteenth-century reception of Luther’s Judenschriften are especially welcome, as are Christian Wiese’s insightful treatment of Jewish and antisemitic Luther lectures in the Kaiserreich and the Weimar Republic and Volker Leppin’s analysis of Luther’s Judenschriften in the light of the editions prior to 1933. Yet, there are some problematic elements as well, including some of the conclusions reached about Protestant reception of the Judenschriften during the Third Reich. These will be addressed (together with the volume’s strengths) after a summary of the contents.

The volume is a product of the conference “The Reception of Luther’s ‘Judenschriften’ in the 19th and 20th Centuries,” which was held at Erlangen University in October 2014. The contributors, who number more than a dozen, represent fields that include Protestant church history, Protestant systematic theology, religion, Jewish studies, and Catholic theology. As the book’s title suggests, the collection of essays covers a broad chronological range; the thematic terrain is wide as well. This breadth is one of the volume’s greatest strengths. The essays addressing nineteenth-century reception of Luther’s Judenschriften are especially welcome, as are Christian Wiese’s insightful treatment of Jewish and antisemitic Luther lectures in the Kaiserreich and the Weimar Republic and Volker Leppin’s analysis of Luther’s Judenschriften in the light of the editions prior to 1933. Yet, there are some problematic elements as well, including some of the conclusions reached about Protestant reception of the Judenschriften during the Third Reich. These will be addressed (together with the volume’s strengths) after a summary of the contents. The first part of the catalog impressively illustrates the instrumentalization of Luther as the “German faith hero” in the first two years of the Third Reich by using photographs and covers of contemporary publications. Several Protestant representatives drew an additional historical and theological continuity line from Luther to Hitler. Publications and celebrations such as the 450th anniversary of the reformer in 1933and the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Bible translation in 1934 illustrate the reference to Luther at this time. Likewise, many new church buildings were named after the reformer, the most well-known example being the Martin Luther Memorial Church in Berlin-Mariendorf, consecrated in 1935. On the theological level, in the early years of the Nazi regime, Luther’s doctrine of the two kingdoms was the center of church-political debates concerning the relationship between the church and the state. But this was increasingly changing in the mid-1930s. As a result of the exclusion of the Jews forced by the National Socialists, Luther’s antisemitic “Jewish writings” were increasingly placed at the center of the reformer’s reception. These writings often served as justification for the persecution of the Jews from a theological point of view. It is somewhat surprising that the section on the state-church relationship is mainly related to the view of the National Socialists, Bonhoeffer, Niemöller, and other representatives of the Confessing Church. The German Christians with their theological line of continuity of Jesus-Luther-Hitler are hardly mentioned in this section.

The first part of the catalog impressively illustrates the instrumentalization of Luther as the “German faith hero” in the first two years of the Third Reich by using photographs and covers of contemporary publications. Several Protestant representatives drew an additional historical and theological continuity line from Luther to Hitler. Publications and celebrations such as the 450th anniversary of the reformer in 1933and the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Bible translation in 1934 illustrate the reference to Luther at this time. Likewise, many new church buildings were named after the reformer, the most well-known example being the Martin Luther Memorial Church in Berlin-Mariendorf, consecrated in 1935. On the theological level, in the early years of the Nazi regime, Luther’s doctrine of the two kingdoms was the center of church-political debates concerning the relationship between the church and the state. But this was increasingly changing in the mid-1930s. As a result of the exclusion of the Jews forced by the National Socialists, Luther’s antisemitic “Jewish writings” were increasingly placed at the center of the reformer’s reception. These writings often served as justification for the persecution of the Jews from a theological point of view. It is somewhat surprising that the section on the state-church relationship is mainly related to the view of the National Socialists, Bonhoeffer, Niemöller, and other representatives of the Confessing Church. The German Christians with their theological line of continuity of Jesus-Luther-Hitler are hardly mentioned in this section. Chosen Nation argues that “Mennonitism should not be understood as a single group—or even as an amalgamation of many smaller groups.” Rather, the book seeks to uncover “what the idea of Mennonitism has meant for various observers” and “how and why interpretations have developed over time” (7). Goossen’s transnational history argues that Mennonites appropriated German nationalism when it was in their interest to do so and suppressed or abandoned it when it became problematic. Into the 1800s, Mennonites had commonly understood themselves to be a global confessional community. As the century wore on, however, they began to portray themselves as “archetypical Germans” (13). As Emil Händiges, the long-time chairman of the progressive Union of Mennonite Congregations in the German Empire (established in 1886), put it, “Do not almost all Mennonites … wherever they may live—in Russia, in Switzerland, in Alsace-Lorraine, Galicia, Pomerania, in the United States and Canada, in Mexico and Paraguay, yes even in Asiatic Siberia and Turkestan—speak the same German mother tongue? Are not the Mennonites, wherever they go, also the pioneers of German language, customs, and culture?” (13). Whether the Mennonites in these far-flung locales—or even in conservative congregations in the new German Empire—understood themselves as the promoters of German culture was another matter entirely.

Chosen Nation argues that “Mennonitism should not be understood as a single group—or even as an amalgamation of many smaller groups.” Rather, the book seeks to uncover “what the idea of Mennonitism has meant for various observers” and “how and why interpretations have developed over time” (7). Goossen’s transnational history argues that Mennonites appropriated German nationalism when it was in their interest to do so and suppressed or abandoned it when it became problematic. Into the 1800s, Mennonites had commonly understood themselves to be a global confessional community. As the century wore on, however, they began to portray themselves as “archetypical Germans” (13). As Emil Händiges, the long-time chairman of the progressive Union of Mennonite Congregations in the German Empire (established in 1886), put it, “Do not almost all Mennonites … wherever they may live—in Russia, in Switzerland, in Alsace-Lorraine, Galicia, Pomerania, in the United States and Canada, in Mexico and Paraguay, yes even in Asiatic Siberia and Turkestan—speak the same German mother tongue? Are not the Mennonites, wherever they go, also the pioneers of German language, customs, and culture?” (13). Whether the Mennonites in these far-flung locales—or even in conservative congregations in the new German Empire—understood themselves as the promoters of German culture was another matter entirely.