Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 24, Number 2 (June 2018)

Review of Manfred Gailus and Clemens Vollnhals, eds., Für ein artgemässes Christentum der Tat: Völkische Theologen im “Dritten Reich”, Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, Göttingen, 2016, 329 pp.

By Robert P. Ericksen, Pacific Lutheran University

This book, as indicated in its title, deals with what must be the most crucial flaw within German Protestant theology in the lead-up to the Nazi era, perhaps a “sickness unto death,” to borrow a phrase from Kierkegaard. This flaw involves a völkisch theology, emphasizing the tight bond between Christian belief and the German people. It involves an artgemäss theology, claiming the necessity of certain racial and cultural qualities for any Germans claiming faith in Jesus and the Christian God. And, though it does not appear in the book title, this flaw involves an “orders of creation” theology, in which certain cultural, political, and racial qualities of the German Volk, as celebrated by Adolf Hitler and National Socialism, could be seen as a binding revelation from God. After an introduction to the topic, fifteen chapters of this book deal with sixteen individuals who help us better understand the complicity of Protestant Christians in the crimes of the Nazi state.

One of the editors of this volume, Manfred Gailus (a member of the editorial board of CCHQ), is a historian known to many or most of us as a prolific author and editor of books on Protestant churches in Nazi Germany. These include his Protestantismus und Nationalsozialismus: Studien zur Nationalsozialistischen Durchdringung des Sozialmilieus Berlin (Berlin, 2001), plus books such as Mir aber zerriss es das Herz: Der stille Widerstand der Elisabeth Schmitz (Göttingen, 2010), and Friedrich Weissler: Ein Jurist und bekennender Christ im Widerstand gegen Hitler (Göttingen, 2017). He also has co-edited books with colleagues, such as Nationalprotestantische Mentalitäten in Deutschland—1870-1970 (Göttingen, 2005), co-edited with Harmut Lehmann; Zerstrittene “Volksgemeinschaft:” Glaube, Konfession und Religion im Nationalsozialismus (Göttingen, 2011), co-edited with Armin Nolzen; as well as this volume co-edited with Clemens Vollnhals.

One of the editors of this volume, Manfred Gailus (a member of the editorial board of CCHQ), is a historian known to many or most of us as a prolific author and editor of books on Protestant churches in Nazi Germany. These include his Protestantismus und Nationalsozialismus: Studien zur Nationalsozialistischen Durchdringung des Sozialmilieus Berlin (Berlin, 2001), plus books such as Mir aber zerriss es das Herz: Der stille Widerstand der Elisabeth Schmitz (Göttingen, 2010), and Friedrich Weissler: Ein Jurist und bekennender Christ im Widerstand gegen Hitler (Göttingen, 2017). He also has co-edited books with colleagues, such as Nationalprotestantische Mentalitäten in Deutschland—1870-1970 (Göttingen, 2005), co-edited with Harmut Lehmann; Zerstrittene “Volksgemeinschaft:” Glaube, Konfession und Religion im Nationalsozialismus (Göttingen, 2011), co-edited with Armin Nolzen; as well as this volume co-edited with Clemens Vollnhals.

The second editor, Vollnhals, also has a career full of important contributions to our understanding of churches in Nazi Germany, beginning with his early study on denazification, Evangelische Kirche und Entnazifizierung, 1945-1949: Die Last der nationalsozialistische Vergangenheit (Munich, 1989). He too has been prolific in co-edited projects, including Mit Herz und Verstand—Protestantische Frauen im Widerstand gegen die NS-Rassenpolitik (Munich, 2013), co-edited with Manfred Gailus; and Die völkisch-religiöse Bewegung im Nationalsozialismus: Eine Beziehungs- und Konfliktgeschichte (Göttingen, 2012), with Uwe Puschner; plus more than a dozen additional edited volumes. Taken together, the work of Gailus and Vollnhals could be the stuff of several seminars on the response of Protestants in Germany to the Nazi state, including analyses of some of the heroes, but especially with an attempt to understand those who found the Nazi state so very attractive. This volume, with its depiction of sixteen völkisch theologians, explores the attraction of Adolf Hitler and National Socialism for German Protestants. It takes us deeply into that Christian stance which, post-1945, strikes so many as so counter to an appropriate understanding of the teachings of Jesus.

All the theologians in this volume had some sort of relationship to the Deutsche Christen, of course, that group of German Protestants who welcomed and cheered the rise of Hitler, waved the Swastika, often wore brown uniforms in church, and tried to disguise or even remove all Jewish elements within the Christian tradition. Some of these stories are well known. Oliver Arnhold writes on Walter Grundmann and his “Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life,” a topic also described for us in the work of Susannah Heschel, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (Princeton, 2008). Grundmann and his so-called “Dejudaization Institute,” supported by the German Protestant Church and its notorious “Godesberg Declaration,” included a large number of seemingly reputable theologians in his project to deny the Jewish origins of Christianity, and even the Jewish origins of Jesus.

A chapter by Dirk Schuster describes Johannes Leipoldt, a professor of New Testament who, after stints at Kiel and Münster, arrived at Leipzig in 1916. Schuster emphasizes in his chapter title Leipoldt’s effort to deny Jesus’ Jewishness, including the quote, “Jesus is far removed from any sort of Jewishness” (189).[1] Leipoldt worked closely with Walter Grundmann, a former student, and became one of the most active co-workers in Grundmann’s Dejudaization Institute, especially influencing the argument—important within the Nazi world—that Jesus could not really have been of Jewish blood. Despite this antisemitic activity, Leipoldt sailed through the transition of 1945. The fact that he never actually joined the Deutsche Christen or the NSDAP allowed him to be fully exonerated by the denazification process, with no attention placed on the heavily antisemitic elements in his scholarship (197). He remained at Leipzig until his retirement in 1954 (190). With his ongoing position at Leipzig and his national and international reputation, including for translations and for work on original sources, Leipoldt’s many antisemitic stereotypes, assumptions, and arguments remained fully “citationable” into the 1980s (201).

We also get a chapter by Hansjörg Buss on Gerhard Meyer. He was a simple pastor in Lübeck, rather than a theologian with a university position; but Buss shows us how completely Meyer was able to develop a church in Lübeck, the Martin Luther Parish, into a place where Germanness counted for far more than received tradition. Catholics had no place in a German church, according to Meyer, nor did Protestants who quarreled over doctrine. Jews had no place whatsoever, whether within the Christian tradition or within Germany. This all grew out of the idea of a “Deutschkirche,” advocated by the antisemitic Bund für Deutsche Kirche (League for a German Church), founded in 1921, which had an especially strong following in Lübeck and Schleswig-Holstein. Meyer, born in Lübeck in 1907, was ordained in 1932 and received his appointment in the Martin Luther Parish in September 1933. Soon he was baptizing with these words, “The Meaning of Baptism is this: Bestowed by the mother’s womb of the world, bound with God from the beginning, this child shall stride as a man of God over German soil” (131). He celebrated a group of confirmands in March 1939, alongside Reichbishop Ludwig Müller, with a similar theology: “We believe that Germany, the land and the community of German brothers and sisters, represents the order of life to which we alone are bound by body and soul” (130). Some months later, in September, shortly before his wedding, this 31-year-old pastor and enthusiast for Hitler and the Nazi ideal, recently called up for military service, died in the invasion of Poland (131).

Stephan Linck describes another pastor from Schleswig-Holstein, Ernst Szymanowski, who quickly gravitated toward the Deutschkirche and its overtly German, racist, and antisemitic concept of Christianity. Born in 1899 and after one year of active duty during World War I, he completed his theological training, was ordained in 1924, and joined the NSDAP already in 1926. He then sought to work his way up within the church, including an attempt to be selected as bishop of Lübeck in 1934, though this effort failed (242-45). Pastor Szymanowski is now better known to us as Ernst Biberstein. This is the name he legally acquired only in 1941, as a way to jettison his Slavic name and solidify his German credentials, which he claimed extended back one thousand years (250). The name-change came after he had joined the SS in 1936, and after he withdrew from church membership in 1938 (248-49), but Biberstein is the name by which he became famous after 1945.

Among Biberstein’s activities during wartime, working under Reinhard Heydrich in the RSHA, Biberstein spent several months as leader of Einsatzkommando 6, murdering thousands of Jews. When placed on trial at Nuremberg in 1948, he explained that he joined the SS because he thought it the most idealistic Nazi organization. When asked about the killing by his Einsatzkommando 6, he said, “Due to my theological development, I found it not only extremely unpleasant, but almost unreasonable, that death sentences should be ordered and enforced under my command.” Did he offer the victims “spiritual assistance,” he was asked, as they were being murdered? No, these victims were Bolsheviks, he said, who advocated godlessness. It was not his role to try to convert them: “One should not throw pearls before swine” (252).

Amidst a great deal of press interest in this pastor/murderer, who acknowledged that at least 2000-3000 victims were shot or gassed to death under his authority, Biberstein was sentenced to death (253). As often happened, that sentence gradually got reduced to incarceration at Landsberg Prison. Working for his release from prison, by 1956 Biberstein denied his own admission at Nuremberg about the thousands of deaths under his command. He also claimed to a representative from the Protestant Church in Neumünster that, despite his having left the church in 1938, “he had always felt himself to be and handled himself as a Christian and a theologian.” Furthermore, “He said . . . simply as his own inner conviction, that it would be good if every pastor’s personal attitude in life would be as decent as his had been” (256). Linck makes clear that the interlocutor reporting on the state of Biberstein’s conscience had been a fellow member of the Nazi Party and an advocate for the Deutsche Christen back in Schleswig-Holstein in the 1930s. Biberstein failed to get his hoped-for permanent return to a clergy position; however, he did gain his release from Landsberg in 1958 and had an opportunity to live outside prison another twenty-eight years before his death in 1986. Linck then quotes Raul Hilberg on Biberstein, “For Biberstein moral boundaries were like the receding horizon. He went toward them but never reached them” (259).

The sixteen chapters in this volume contain many additional examples of völkisch Protestant theologians and clergy who followed the path of German nationalism, racism, and an increasingly aggressive attack upon the Jewish place within the Christian tradition, or even within Germany itself. Rainer Hering describes Franz Tügel, the Bishop of Hamburg, who joined the Nazi Party in 1931, after a careful reading of Nazi documents, including Mein Kampf. In 1932 he expressed hope for a “rebirth of the German nation” under Hitler’s leadership. As for the projected harsh treatment of Jews, he saw no reason for the church to criticize Nazi intentions, describing Jews as a “pestilence” and “the great danger” for Germany (141-42).

Gerhard Lindemann describes a parallel example, Martin Sasse, the Bishop of Thuringia. Born in 1890, Sasse fought in World War I from 1914-1918. Then, after the war, he joined in Freikorp battles against communists and revolutionaries. After these years in uniform, Sasse returned to his theological studies and received an appointment and ordination in 1921. In March 1930 he joined the NSDAP and that fall he accepted a pastorate in Thuringia, a very brown region with an especially strong cohort of Deutsche Christen. By January 1934 Sasse had risen to Bishop of the Thuringian Church (156). From this position he gave full support to the Nazi state and Nazi ideology. This included, for example, praise for the November 1938 Pogrom as a necessary measure and part of the “world historical struggle against the Volk-destroying spirit of the Jews” (161). He was among those bishops who signed the Godesberg Declaration of 1939, which led to the creation of Walter Frank’s Dejudaization Institute. Sasse supported the radical Thuringian Deutsche Christen, even agreeing with their claim that the Jewish Old Testament had no place in the Christian Bible (163). As for the Holocaust, by August 1941 Sasse’s office produced a public announcement describing this as the “moment in which God’s hand reaches out to destroy precisely this people” (167), apparently blaming the murder of Jews on God, rather than Germans. Sasse held his position as bishop until his death in 1942, an early demise caused by problems with his heart.

Dagmar Pöpping tells the complex story of Herman Wolfgang Beyer, born in 1898, who “grew up” serving in World War I from 1916-1918 and watching all his friends die. He returned to Germany a pacifist and idealist, with high hopes for the Weimar Republic and a peaceful future. Then began a series of lurches to the right and left. The Versailles Treaty cost him his pacifism and his support of Weimar, but, while studying theology, he first stood on the left with a group who designated themselves “readers” of Die Christliche Welt, a liberal Protestant journal. He completed his theological training, however, with Karl Holl in Berlin, the founder of a “Luther Renaissance” and teacher of many of the most völkisch of the next generation of Protestant theologians, men such as Emanuel Hirsch and Paul Althaus. Beyer befriended both men by the mid-1920s, a useful step in his career, and by the age of twenty-eight, he secured a professorship in church history at Greifswald (262-65). In 1933 he greeted the rise of Hitler with an enthusiasm as exuberant as that of his two mentors, beginning and ending every future lecture with “Heil Hitler.” As for the Protestant Kirchenkampf (Church Struggle), Beyer joined the Deutsche Christen in the spring of 1933, and also joined the SA (Nazi Stormtroopers) that fall. Surprisingly, though, Beyer became disillusioned with the harsh tactics of the DC under Reichbishop Müller in 1934 and switched his allegiance to the Confessing Church, which he maintained also when he moved to a chair at Leipzig in 1936. Throughout these changes in his church politics, he remained loyal to the Nazi state, a position not entirely uncommon among his fellow members of the Confessing Church.

When World War II broke out, Beyer volunteered to serve as a chaplain. He is interesting to us at least in part because he kept a detailed diary of his experiences on the Eastern Front. This included his personal observation of the murder of innocents, whether the shooting of 400 disabled residents of a hospital for convenience sake, or the murder of thousands and thousands of Jews. Pöpping reports on Beyer’s efforts to explain and justify these murders. Regarding the 400 disabled people dispatched by bullet, he writes, “I understand that the poor guys must be killed. One cannot simply let them run free. They would then only perish, naturally” (272). As for the mass murder of Jews, he comments, “The struggle against Jews must occur. But it has assumed a terribly hard shape…. The curse under which these people live is being fulfilled in a horrible manner” (273). Despite the horrors, Beyer taught his troops that killing Russians and Jews was necessary. He blamed the Enlightenment as a root cause, with its emphasis on equality and human rights, which finally led to Bolshevism and atheism. “We see it on the dull, staring, expiring faces of the Soviet prisoners of war who pass us by. The human being in this world has stopped being truly human” (270). True to the most hateful antisemitism of the early twentieth century, especially in its Nazi version, Beyer then made the connection to Jews, the most intensively victimized group being murdered by German forces. He explained to his troops that Jews had invented Bolshevism and, without attachment to the Christian God, both Jews and Bolsheviks had lost their souls, were no longer human. Pöpping then summarizes Beyer’s conclusion: “A human without a soul is no longer required to be treated as human” (271).

This self-description by Beyer of his work as a Protestant chaplain at the center of the Eastern Front, which was also the center of the Holocaust, could be understood simply as the rather ugly final result of völkisch theology, a theology which elevated Germany’s wounded and intense self-identity above prior Christian norms and ideals that had developed over two millennia. I appreciate Pöpping’s work on this man. I do wonder, however, whether her stance at the start of this chapter is too gentle, too understanding of the man under her gaze. She cites two historians, Doris Bergen and Felix Römer, who she accuses of describing chaplains “as ‘propagandists’ and ‘accomplices’ of the Vernichtungskrieg.”[2] In Pöpping’s view, “That would be too simple, to be content only with exposing what is morally unacceptable from today’s point of view” (261). She also cites the work of Antonia Leugers and Martin Röw for presentations of this softer approach, authors who raise the possibility of Catholics and chaplains staying moral within an immoral war.[3] These are hardly simple issues, but I am left wondering what could be seen as deficient in a “morality of today” that suggests murder and genocide are immoral. Was Beyer’s complete commitment to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi state a good decision? Should we approve of his extra effort to encourage troops not to shrink from their task? Is it wrong to connect the dots in his complicated development as a theologian and suggest that something has gone dreadfully wrong when his loyalty to Germany and to Hitler have him defending the murders perpetrated and/or viewed by troops under his spiritual guidance?

This brings me to two of the most prominent theologians dealt with in this volume, Paul Althaus and Emanuel Hirsch, theologians who befriended Hermann Wolfgang Beyer and may well have inspired his virtually complete loyalty to Hitler and the Nazi state. I am familiar with Althaus and Hirsch, since I focused on these two plus Gerhard Kittel in my Theologians under Hitler more than thirty years ago.[4] Tanja Hetzer’s chapter on Paul Althaus is based on her 2009 book him.[5] She begins with one of my favorite quotations from Althaus, at least in terms of its importance: his notable claim that Protestant churches in Germany “greeted the turning point of 1933 as a gift and miracle from God” (69). He published that statement in 1933 and it certainly guided his overall response to the rise of Hitler and National Socialism. Hetzer argues that Althaus’s völkisch nationalism, a central aspect of his theology, was heavily influenced by his experience as a wartime pastor in Lodz during World War I, as well as his marriage to Dorothea Zielke, born in Warsaw to a German family long-settled in Poland. Of course, Althaus also was influenced by his bitterness over Germany’s loss in that First World War. During the war and throughout the 1920s, Althaus preached a love for the Fatherland and a claim that the Protestant church should speak to the bond between Germans, the German Lutheran tradition, and the beleaguered German nation. Hetzer does a very nice job of showing that Althaus’s “Orders of Creation” theology and his emphasis on “Order” and “Authority”—all developed in the early years of his career—made him ready to proclaim Hitler a “gift and miracle from God” and to give mostly enthusiastic support to the regime.[6] Hetzer shows that this stance was rooted in his völkisch obsession: “With Althaus it is vital to observe how the concept of the Volk became a new ethical reference point for theology” (76).

As for Althaus’s view of Jews, Hetzer points out that he often spoke in “cultural codes” and avoided the crudest expressions of antisemitism; but she effectively shows that a harsh antagonism toward Jews lay deeply embedded within his work.[7] During Weimar he apparently had no personal connection to important figures, such as Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig, but he spoke of them like a “schoolmaster” and without respect (76). Hetzer effectively shows that Althaus’s “Orders of Creation” theology lays the groundwork for antisemism in its insistence that God created the various “orders” in existence, including nations and races. So it is no surprise that in the opening battles of the Church Struggle in 1933, when Deutsche Christen demanded the application of the Aryan Paragraph within the Protestant church, Paul Althaus and Werner Elert, his colleague at Erlangen, agreed that Germans had every right to include race among the requirements for clergy in the German Protestant Church (85-88). Althaus and Elert then co-authored the Ansbacher Ratschlag, an attack against the Barmen Declaration that was enthusiastically greeted by Deutsche Christen.

Hetzer concludes her chapter by pointing out that a “loyalty of the second generation” remains in place, giving Althaus a softer treatment than he deserves. This includes Walter Sparn, a systematic theologian, who claims “Althaus without doubt was never a National Socialist,” though he may have been a “political romantic” who advocated a “revolution from the right.”[8] Such a view gives little weight to Althaus’s assessment of Hitler as “a gift and miracle from God.” Hetzer also critiques the recent biographer of Althaus, Gotthard Jasper of Erlangen University.[9] The subtitle of his 2013 book, “Professor, Prediger und Patriot seiner Zeit,” certainly buries Althaus’s enthusiastic and very public support of Hitler and National Socialism with that innocuous use of “patriot,” as does Jasper’s treatment of Althaus in general. Hetzer credits Jasper with his presentation of much material, “without, however, considering problematic statements by Althaus according to his actual words or requiring of Althaus posthumous responsibility for what he actually wrote and said” (95).

I quite agree with Hetzer’s conclusion that, despite his clear political stance, “Althaus was viewed in the history of theology after 1945 not as a participant in history, but as a victim of his own ideas, above all when it involved his antisemitic undertakings” (95). I would only mention that my book from 1985 on Althaus, Hirsch and Kittel gets but one footnote in this chapter, and that is to substantiate Althaus’s “reputation as a mediator” and the fact that he is “viewed still today as a theologian with a self-chosen stance in the middle” (70). I do use the term “mediator,” and I describe him as less radical in his support of Nazi politics than either Emanuel Hirsch or Gerhard Kittel. However, this by no means hides my criticism of his very important and enthusiastic place in support of Hitler and Nazism. A large number of the quotations used by Hetzer in this chapter also appear in my book. Furthermore, Hetzer does show Althaus as a moderate of sorts, at least for his place and time. He tended to use coded and vague language. Many or most could see his attack on Jews, but he was not as outspoken or blatant as many others treated in this volume by Gailus and Vollnhals. I appreciate Hetzer’s analysis of Althaus’s work, which I think takes an important step forward in recognizing the antisemitic foundations of his scholarship. I also agree that Sparn from 1997 and Jasper from 2013 are too apologetic in their treatment of Althaus, but I remain a bit disappointed that my work in 1985 is not clearly separated from those two.

Heinrich Assel writes about Emanuel Hirsch, who was one of the main figures in his 1994 book on the Luther Renaissance from 1994.[10] This chapter also builds upon Assel’s very thorough reading of appropriate additional sources and documents to which he has gained access, even though Hirsch’s own Nachlass has been carefully restricted from public view or scholarly use. In particular, Assel has accessed a massive correspondence between Hirsch and the right-wing publicist, Wilhelm Stapel, which extended from 1931 until Stapel’s death in 1954 (47). In my view, Assel rightly places Hirsch at the very center of the völkisch theology that is at the heart of Gailus and Vollnhals’ book, and which drew Hirsch to his enthusiastic public support of Hitler by April 1932.

Hirsch became the leading theological advisor to and supporter of the Deutsche Christen and Reichbishop Ludwig Müller in 1933. He then openly designated himself a “political theologian” by 1934, taking the side of Ludwig Müller’s church government. As the Müller phase of church politics proved ineffective, Hirsch worked to support the “Gleichschaltungspolitik” of the Nazi state, privileging Hitler’s totalitarian rule over his two other loyalties, those to church and state (44). As for the Nazi stance on Jews, Hirsch moved from his earlier prejudice against Jews, which was primarily religious and cultural, to “an openly racist antisemitism.” Though others blanched at the destructiveness of the November Pogrom in 1938, he was “passionately in favor,” welcoming it as a way to push Jews toward emigration. As the murderous nature of the war in Eastern Europe and the specific annihilation of Jews developed, Hirsch was kept informed by his contacts in the Nazi Party and the SS. His response was to “give unlimited support to this politics of annihilation” (56).

Assel’s access to the Hirsch/Stapel correspondence, often comprising several letters per week and sometimes more than one letter per day, illustrates for us the overwhelming confidence placed by Hirsch and Stapel in the German Volk and the Nazi state, a convergence designed to bring Germany back to its rightful place in the world. We also learn about their harsh antisemitism. However, we do see Wilhelm Stapel losing at least some of his nerve in the last, more brutal years of the Nazi regime, while Hirsch remained firm. After the failed July 20, 1944 attempt on Hitler’s life, Stapel wrote of his sympathy for the plotters. Hirsch wrote back with ten full pages, expressing unapologetic approval of Nazi church politics, Nazi foreign policy, and also the harsh judgments of the People’s Court against the conspirators. He speculated in that letter, written in the bleak summer of 1944, on two possible outcomes of the war: a German victory, leading to a healthy nation and national church, or a German defeat and the collapse of Christianity in Germany (60-64).

In an attempt to understand the uncompromising persistence of Hirsch’s stance, Assel points out one very important factor in his life, poured out in this long letter to Stapel. That is his deep grief over his son, Peter, fallen in 1941. Assel places this in the context of a “Myth of the Fallen,” the belief that only a German victory would justify the many deaths spread over the two costly wars in Hirsch’s lifetime (63-64). In my work on Hirsch, I point to his medical deferment in August 1914 at the start of World War I. This embarrassed or even haunted him, and I speculate that it might help explain the aggressive nationalism and militarism in his work.[11] The World War II loss of his son would only have multiplied that psychological impact, of course. Even though Stapel and Hirsch each lost some of their influence during the last years of the Nazi regime, Stapel more so than Hirsch, we learn from their letters that Hirsch refused to blame Hitler or the Nazi state, even after 1945, and even after the horrors of the Nazi regime had been condemned by most of the world. In my work on Hirsch, I quoted colleagues who said he never changed his politics after 1945 or admitted that he had been mistaken.[12] I was criticized for this by some friends of Hirsch. Assel’s chance to read portions of Hirsch’s correspondence now confirm I was right on that score (49).

Before leaving Assel’s treatment of Hirsch, I will once again mention my Theologians under Hitler from 1985, which dealt extensively with Hirsch. I also wrote about Hirsch in my chapter on the Göttingen Theological Faculty, first published in Die Universität Göttingen unter dem Nationalsozialismus in 1987.[13] Neither is cited by Assel. This is obviously a minor complaint. In one instance, however, I believe that Assel’s treatment of Hirsch’s postwar circumstances would benefit from my work. In May 1945, Hirsch grabbed the chance of a medical retirement, justified by his failing eyesight, in order to avoid removal for his pro-Nazi stance. This meant he circumvented his essentially certain dismissal by the English occupiers, without pay, followed by a denazification process of uncertain outcome. Instead, besides avoiding the humiliation of being thrown out of his university, he also secured a life-long pension, even if reduced by his choice of an early medical retirement, and he secured the right to stay in his beautiful, large home on the Schiller Meadow. Assel refers to a brief postwar period when the Hirsch family did not receive funds as a “bureaucratic mistake,” which is probably true. But then he adds, “Without having to go through a denazification process, Hirsch was rehabilitated as emeritus” (57).

This version of Hirsch’s postwar transition slides past an experience that was traumatic for many university professors whose politics had been enthusiastically pro-Nazi, and especially so for Hirsch. It also ignores my extensive treatment of the actual, bitter process that ensued. His medical retirement left him without any connection to his university. At the age of fifty-seven, he was not ready to retire. As he had been nearly blind since the 1920s, he clearly hoped to reverse the convenient medical excuse used in May 1945 and resume his career. Furthermore, the eventual return of most Nazi-tinged professors to their positions would have encouraged his hopes. However, despite his own efforts and energetic attempts by a few of his friends, he never could bring himself back into the good graces of Göttingen University or its Theological Faculty. From May 1945 until his death in 1972, Hirsch was never rehabilitated. He never received emeritus status, he never received announcements of events or invitations, his name was never included in university publications, and he had no formal connection whatsoever with his former faculty.[14] (He also never received the blue plaque on his home, marking the place where very important university scholars, such as his rival, Karl Barth, had lived.) This postwar result placed Hirsch among the very few, most heavily implicated Nazis not able to return to their positions at Göttingen, part of a similar pattern at other universities as well. The only students with whom Hirsch came in contact in those postwar years met with him in his home for regular meetings of an irregular, unofficial, private seminar. Some within that informal coterie became known as the “Hirsch Circle.” This group long hoped to resurrect Hirsch’s reputation as a theologian from his loss of respect in the postwar era, but largely without success. Was the postwar denial of honor or respect appropriate? Assel’s work goes a long way toward establishing that Hirsch’s devotion to Adolf Hitler was thoroughgoing. If we do not approve of Hitler’s judgment, ideas and politics, it is difficult to approve of Hirsch’s. Furthermore, the völkisch nature of the Protestant theology at the center of Hirsch’s work made his politics far more than a side issue in his career.

In the context of the Hirsch-Stapel correspondence, I will also mention Clemens Vollnhals’ chapter on Wilhelm Stapel. During the Weimar Republic, Stapel edited and wrote prolifically in the right-wing, nationalistic journal, Deutsches Volkstum. He also rose to leadership within the Hanseatic Verlag, the publisher of Deutsches Volkstum and later the publisher of the Völkischer Beobachter and other Nazi publications. Though Stapel never had an academic career, he and Hirsch were natural allies in their commitment to a völkisch Protestant theology and a nationalistic, right-wing revolution against the Weimar Republic. In 1933 Stapel greeted the rise of Hitler with Die Kirche Christi und der Staat Hitlers (“Christ’s Church and Hitler’s State”).[15] He supported the Deutsche Christen, even after the Sports Palace Scandal of November, 1933, in which 20,000 enthusiasts applauded the removal of the Old Testament and other proposed steps into open heresy (110). All of this fit into Stapel’s understanding of a special law, a Volksnomos, given by God to every nation, and, in the German case, God’s creation of a leading nation among nations, ready to build a new European empire in the manner of ancient Rome (101-04). There was no place for Jews in this venture. Stapel praised the May 1933 burning of Jewish books. He accepted the total separation of Jews from the German nation, even before the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. In 1938 he wrote, “Jews in the German Reich are inferior. Their place in Germany is a result of the stance they have taken against us in our struggle for German honor” (113-14). Stapel also worked within Grundmann’s Dejudaization Institute. Vollnhals does show that Stapel’s stomach for harsh measures had its limits. He regretted the disorderly broken glass of November 1938. In a letter to Paul Althaus in January 1942, as deportations of Jews had begun, he admitted that what was happening to Jews was horrible. Despite the horrors, however, even in 1942 he stood by his earlier, harsh assessment of the Jewish question, “so that later it is not lost … why the symbiosis pushed for by the Jews was impossible” (114). Both Hirsch and Stapel represented the radical vision of a special place for the German Volk within God’s plan, along with a willingness to bind the resulting völkisch Protestant theology to the brutal, totalitarian regime created by Adolf Hitler.

Für ein artgemässses Christentum der Tat is a very useful book. Besides the chapters described above, it includes an excellent introductory chapter by Gailus and Vollnhals, plus additional treatments of men like Reinhold Seeberg, described by Stefan Dietzel as an important professor at Berlin in the age of Harnack, who lived into the first two years of the Nazi state and gave both eugenics and the NS racial ideology his support. Andre Postert offers us a chapter on Wolf Meyer-Erlach, the famously antisemitic and under-qualified professor who became Rektor at the University of Jena and later worked in Grundmann’s Dejudaization Institute. Ulrich Peter writes about Walter Schultz and Heinrich Schwartze, two Protestant pastors, the latter also a bishop, who negotiated complicated transitions from their support of National Socialism to their place in the postwar German Democratic Republic. Isabella Bozsa describes the career of Eugen Mattiat, a small-town pastor awarded for his political reliability with a professorship at Göttingen University. Remarkably under-qualified, he quickly lost that position under denazification, but eventually became once again a small-town pastor. Manfred Gailus gives us a final chapter, describing Walter Hoff, an enthusiastic pro-Nazi pastor in Berlin. After volunteering at nearly fifty to serve in his second World War, he returned on leave to brag about his exploits. Then, responding angrily to an “unwarlike” circular letter sent to Berlin pastors in 1943, he emphasized the need to fight against “World Jewry and its evil representatives,” uninhibited by any soft Christian ideal of “mercy.” He added that in Soviet Russia he himself had “helped liquidate” hundreds of Jews (311).

Not all stories in this volume include Protestant pastors bragging about murdering Jews! All of the stories, however, provide examples of Protestants who idolized the German Volk, gave their heart to Adolf Hitler, and both accepted and promoted the antisemitism of the Nazi state. From our present perspective, these stories give us good reason to rethink our understanding of the Christian relationship to Jews, to nation, to race, and to the compassionate side of Jesus’ ethic. Gailus and Vollnhals have assembled a useful and convincing treatment of the problems that arise when Christians think someone like Adolf Hitler is on their side.

[1] Please note that all translations are by the author of this review.

[2] Pöpping cites as representatives of this point of view, Doris Bergen, “’Germany is our Mission – Christ is our Strength!’ The Wehrmacht Chaplaincy and the ‘German Christian’ Movement,” in Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture, 66 (1997), 522-36; and Felix Römer, Der Kommissarbefehl: Wehrmacht und NS-Verbrechen an der Ostfront 1941-42, Paderborn, 2008, 510 ff.

[3] See Antonia Leugers, “Opfer für eine grosse und heilige Sache: Katholisches Kriegserleben im nationalsozialistischen Eroberungs- und Vernichtungskrieg,” in Friedhelm Boll, ed., Volksreligiosität und Kriegserleben, Münster, 1997, 157-74; and Martin Röw, Militärseelsorge unter dem Hakenkreuz. Die Katholische Feldpastoral 1939-1945, Paderborn (2014), who, according to Pöpping, suggests (p. 448) that chaplains were “unwilling instruments” in the war of extermination.

[4] Robert P Ericksen, Theologians under Hitler: Gerhard Kittel, Paul Althaus and Emanuel Hirsch, New Haven, 1985.

[5] Tanja Hetzer, “Deutsche Stunde.” Volksgemeinschaft und Antisemitismus in der politischen Theologie bei Paul Althaus, Munich, 2009. It should be noted that most of the chapters in this book by Gailus and Vollnhals are based on book-length treatments by the authors, so that this volume becomes a useful distillation of a broad range of work.

[6] Hetzer does not mention my treatment of a possible change of heart in Althaus by 1938. His blatantly political publications cease after 1937 and family stories suggest some disillusionment. Althaus’s son Gerhard, born in 1935, told me of a family memory according to which Althaus at the dinner table denounced the November 1938 Pogrom. Gerhard himself remembered a conversation on holiday at Tegernsee in August 1943, when an officer returned from the Soviet front came back with the family from a Sunday service. As an eight-year-old boy, he overheard a story of camps at which civilians, women and children, and unarmed Soviet prisoners were shot. Afterwards, according to Gerhard, his father no longer spoke of winning the war, but of “bloodguilt,” including toward Jews. See Ericksen, 94-98.

[7] In the above-mentioned interview, Gerhard Althaus, who studied theology with his father and became a pastor, told me he questioned his father in the 1950s about the antisemitism rife in Nazi Germany. His father simply responded, “You have not experienced the Jews.” See Ericksen, 109.

[8] See Walter Sparn, “Paul Althaus,” in Wolf-Dieter Hauschild, ed., Profile des Luthertums, Gütersloh 1997, 1-26.

[9] Gotthard Jasper, Paul Althaus (1888-1996). Professor, Prediger und Patriot seiner Zeit, Göttingen, 2013.

[10] Heinrich Assel, Die Lutherrenaissance – Urspringe, Aporien und Wege: Karl Holl, Emanuel Hirsch, Rudolf Hermann (1910-1935), Göttingen, 1994.

[11] See Ericksen, 127.

[12] See Ericksen, 193.

[13] See Robert P. Ericksen, “Die Göttinger Theologische Fakultät im Dritten Reich,” in Heinrich Becker, Hans-Joachim Dahms, and Cornelia Wegeler, eds., Die Universität Göttingen unter dem Nationalsozialismus, Munich, 1987 and 1998, 75-101.

[14] See Ericksen, Theologians, 191-93. See also Ericksen, “Die Göttinger Theologische Fakultät im Dritten Reich,” 90-93.

[15] Wilhelm Stapel, Die Kirche Christi und der Staat Hitlers, Hamburg, 1933.

This sense of observing and interpreting like a guest whose eyes are being opened by degrees to something new and unexpected is certainly one of the strengths of the book. It makes Newell himself something of a tourist – in the best sense – and equally an attractive introducer to readers coming to the same questions afresh. The vital presence at the heart of the story is the pastor of the Nikolaikirche himself, Christian Führer, who in 1989 opened the doors of the church to all people – and, in particular, to many who were disaffected by the Communist state – so that they could meet together, light candles, share what was important to them all and find new ways to insist upon these things in a world of repression and intimidation.

This sense of observing and interpreting like a guest whose eyes are being opened by degrees to something new and unexpected is certainly one of the strengths of the book. It makes Newell himself something of a tourist – in the best sense – and equally an attractive introducer to readers coming to the same questions afresh. The vital presence at the heart of the story is the pastor of the Nikolaikirche himself, Christian Führer, who in 1989 opened the doors of the church to all people – and, in particular, to many who were disaffected by the Communist state – so that they could meet together, light candles, share what was important to them all and find new ways to insist upon these things in a world of repression and intimidation.

In Reading and Rebellion in Catholic Germany, Jeffrey Zalar likewise boldly challenges the existing historiography concerning the German Catholic milieu and its culture of reading, a topic that perhaps is less central to historians of modern Germany, but still important, nevertheless. For those who study religious history, especially that of the Catholic Church in Germany, Zalar’s findings have major implications for understanding the inner-workings of the Catholic milieu. For years, historians have portrayed the milieu as “an insular subculture, whose boundaries were policed by an authoritarian clergy” (8).

In Reading and Rebellion in Catholic Germany, Jeffrey Zalar likewise boldly challenges the existing historiography concerning the German Catholic milieu and its culture of reading, a topic that perhaps is less central to historians of modern Germany, but still important, nevertheless. For those who study religious history, especially that of the Catholic Church in Germany, Zalar’s findings have major implications for understanding the inner-workings of the Catholic milieu. For years, historians have portrayed the milieu as “an insular subculture, whose boundaries were policed by an authoritarian clergy” (8). Griech-Polelle begins with the rise of religious antisemitism—rooted in the concept of Jews as “Christ-killers’’—in the biblical accounts of Jesus’ arrest, death, and resurrection. With the emergence of Christianity came the belief that the Early Church was the “New Israel” which replaced the Jews as God’s chosen people (10-11). Tracing the loss of Jewish rights in the late Roman Empire, the author shows how the Codex Theodosianus began to impose restrictions on Jews and to generate the segregating language that would shape the medieval era. Through the period of the crusades and on into the Middle Ages, Griech-Polelle explains important incidents in the history of Jewish persecution, but beyond that, she endeavours to outline the way a particular kind of antisemitic language emerged in, for example, tropes like the Wandering Jew or the blood libel. A short section on Thomas Aquinas shows how he built on Augustine’s notion of the preservation of the Jews as a witness to the truth of both the Hebrew scriptures and the Christian gospels, adding that the Jews were people with souls that needed to be saved. “Somehow, Jews were to be converted voluntarily—despite the persecutions and horrendous depictions of Jews as being in league with the devil, desecrating the Host, and reenacting the crucifixion of Jesus” (20). This chapter on the history of religious antisemitism continues with the medieval expulsions of Jews from various European countries and follows the story through the Renaissance and Reformation, the emergence of a substantial Jewish community in Poland, and the impact of the Enlightenment, French Revolution, modern nationalism, and post-1848 reactionary politics. It closes with the persecution faced by Jews in Tsarist Russia.

Griech-Polelle begins with the rise of religious antisemitism—rooted in the concept of Jews as “Christ-killers’’—in the biblical accounts of Jesus’ arrest, death, and resurrection. With the emergence of Christianity came the belief that the Early Church was the “New Israel” which replaced the Jews as God’s chosen people (10-11). Tracing the loss of Jewish rights in the late Roman Empire, the author shows how the Codex Theodosianus began to impose restrictions on Jews and to generate the segregating language that would shape the medieval era. Through the period of the crusades and on into the Middle Ages, Griech-Polelle explains important incidents in the history of Jewish persecution, but beyond that, she endeavours to outline the way a particular kind of antisemitic language emerged in, for example, tropes like the Wandering Jew or the blood libel. A short section on Thomas Aquinas shows how he built on Augustine’s notion of the preservation of the Jews as a witness to the truth of both the Hebrew scriptures and the Christian gospels, adding that the Jews were people with souls that needed to be saved. “Somehow, Jews were to be converted voluntarily—despite the persecutions and horrendous depictions of Jews as being in league with the devil, desecrating the Host, and reenacting the crucifixion of Jesus” (20). This chapter on the history of religious antisemitism continues with the medieval expulsions of Jews from various European countries and follows the story through the Renaissance and Reformation, the emergence of a substantial Jewish community in Poland, and the impact of the Enlightenment, French Revolution, modern nationalism, and post-1848 reactionary politics. It closes with the persecution faced by Jews in Tsarist Russia. With the excellent new book by Dirk Schuster, the scholarship reaches an important milestone. The apologetic tone is entirely absent and instead we have a work by a very thoughtful scholar who examines archival data, weighs and evaluates new evidence, and draws sharp and strong conclusions. Schuster represents a new generation of young German scholars seeking historical accuracy rather than defending the church or making excuses for individual theologians.

With the excellent new book by Dirk Schuster, the scholarship reaches an important milestone. The apologetic tone is entirely absent and instead we have a work by a very thoughtful scholar who examines archival data, weighs and evaluates new evidence, and draws sharp and strong conclusions. Schuster represents a new generation of young German scholars seeking historical accuracy rather than defending the church or making excuses for individual theologians. A few key conceptions and realities are at the forefront of Junginger’s study, which is a translation of a revised version of the author’s Habilitation thesis. First, the author seeks to demonstrate that Nazi-era “Jew research,” which purported to pose scholarly answers to the “Jewish Question” but in fact aimed at supporting anti-Jewish policies – was carried out at German universities in a manner that mutually reinforced religious and racial antisemitism. Thus, the book focuses on the religious aspect of modern antisemitism – even while recognizing with great care that “religious stereotypes coalesce with a racial explanation of the world” (ix). Second, the University of Tübingen’s centuries-long role as “an intellectual stronghold against Judaism” (x) culminating in its essential function as a locus of Nazi Judenforschung, is emphasized. Finally, theoretical and practical antisemitism converged during the Holocaust, as typified here by Junginger’s examination of the biographies of roughly a dozen war criminals who, the author demonstrates, were responsible for the deaths of several hundred thousand European Jews during the Shoah.

A few key conceptions and realities are at the forefront of Junginger’s study, which is a translation of a revised version of the author’s Habilitation thesis. First, the author seeks to demonstrate that Nazi-era “Jew research,” which purported to pose scholarly answers to the “Jewish Question” but in fact aimed at supporting anti-Jewish policies – was carried out at German universities in a manner that mutually reinforced religious and racial antisemitism. Thus, the book focuses on the religious aspect of modern antisemitism – even while recognizing with great care that “religious stereotypes coalesce with a racial explanation of the world” (ix). Second, the University of Tübingen’s centuries-long role as “an intellectual stronghold against Judaism” (x) culminating in its essential function as a locus of Nazi Judenforschung, is emphasized. Finally, theoretical and practical antisemitism converged during the Holocaust, as typified here by Junginger’s examination of the biographies of roughly a dozen war criminals who, the author demonstrates, were responsible for the deaths of several hundred thousand European Jews during the Shoah. Commendably, the editors cover the various levels of complicity and resistance in their selection of biographical reconstructions. They do so systematically by dividing the volume into four parts. The first and longest part introduces the biographies of clergymen who embraced Nazi ideology and identified with the Deutsche Christen – the “German Christians,” a group within the Protestant parishes that saw no contradiction between Hitler and Luther, between Nazi ideology and church teachings (Knabe; Münnich; Coch; Fügner; Bohland; Axt). The second part covers four men belonging to the so-called “Mitte,” the center, who tried to walk a middle path between radicalized and Nazi-supporting clergy and those who opposed the Nazi takeover of church and society (Herz; Bruhns; Loesche; Gerber). The third and shortest part introduces two biographies of men of the Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche), who prioritized faith in Christ over nationalist and völkisch ideologies and (partially) resisted the Nazi regime (von Kirchbach; Delekat). The last part documents the biographies of churchmen who were persecuted by the Nazis for political and racial reasons, including Protestant ministers who were classified as Jews (or mix-blooded) by the 1935 Nuremberg Laws (Stempel; Kaiser; Gottlieb; Starke; Grosse).

Commendably, the editors cover the various levels of complicity and resistance in their selection of biographical reconstructions. They do so systematically by dividing the volume into four parts. The first and longest part introduces the biographies of clergymen who embraced Nazi ideology and identified with the Deutsche Christen – the “German Christians,” a group within the Protestant parishes that saw no contradiction between Hitler and Luther, between Nazi ideology and church teachings (Knabe; Münnich; Coch; Fügner; Bohland; Axt). The second part covers four men belonging to the so-called “Mitte,” the center, who tried to walk a middle path between radicalized and Nazi-supporting clergy and those who opposed the Nazi takeover of church and society (Herz; Bruhns; Loesche; Gerber). The third and shortest part introduces two biographies of men of the Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche), who prioritized faith in Christ over nationalist and völkisch ideologies and (partially) resisted the Nazi regime (von Kirchbach; Delekat). The last part documents the biographies of churchmen who were persecuted by the Nazis for political and racial reasons, including Protestant ministers who were classified as Jews (or mix-blooded) by the 1935 Nuremberg Laws (Stempel; Kaiser; Gottlieb; Starke; Grosse). Among the incompatibilities cited by the authors are the AfD’s denigration of vulnerable groups (especially migrants and Muslims), its insistence on a homogeneous German Leitkultur, its political strategy (deliberate provocations and insults, distortions and “alternative facts,” manufacturing or intensifying anxieties), and its invocation of Christianity as an element of national identity rather than a universal faith and system of values. Nevertheless, they recognize that individual Christians have played a key role as founders and leaders of the party (including Frauke Petry, Bernd Lucke, and Konrad Adam on the Protestant side and Jörg Meuthen on the Catholic side). The group “Christen in der AfD” is another indicator that the party has made inroads among Christians, though very few pastors and priests have endorsed the AfD and many have been outspoken in their opposition.

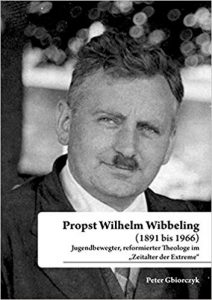

Among the incompatibilities cited by the authors are the AfD’s denigration of vulnerable groups (especially migrants and Muslims), its insistence on a homogeneous German Leitkultur, its political strategy (deliberate provocations and insults, distortions and “alternative facts,” manufacturing or intensifying anxieties), and its invocation of Christianity as an element of national identity rather than a universal faith and system of values. Nevertheless, they recognize that individual Christians have played a key role as founders and leaders of the party (including Frauke Petry, Bernd Lucke, and Konrad Adam on the Protestant side and Jörg Meuthen on the Catholic side). The group “Christen in der AfD” is another indicator that the party has made inroads among Christians, though very few pastors and priests have endorsed the AfD and many have been outspoken in their opposition. Wibbeling had just completed his theological examinations and practical training for the ministry when the First World War began. He fought, eventually becoming an officer, married shortly after the war ended, and was ordained in 1919. His subsequent career showed his lifelong commitment to the renewal and stability of his church as well as his own strong social-political convictions. His political leanings were socialist. He began his ministry as a youth pastor in the coal-mining town of Bochum in the Ruhr valley, where he reached out to working class, Catholic, socialist, and other youth organizations in the region, creating a coalition that focused especially on the problems of alcoholism among youth. A non-church colleague described him in those years as someone “who didn’t act like a pastor at all, avoided church language and was familiar with and understood the socialist movement.”

Wibbeling had just completed his theological examinations and practical training for the ministry when the First World War began. He fought, eventually becoming an officer, married shortly after the war ended, and was ordained in 1919. His subsequent career showed his lifelong commitment to the renewal and stability of his church as well as his own strong social-political convictions. His political leanings were socialist. He began his ministry as a youth pastor in the coal-mining town of Bochum in the Ruhr valley, where he reached out to working class, Catholic, socialist, and other youth organizations in the region, creating a coalition that focused especially on the problems of alcoholism among youth. A non-church colleague described him in those years as someone “who didn’t act like a pastor at all, avoided church language and was familiar with and understood the socialist movement.” As Rudolph notes in her introduction, however, recent research has yielded new information about the group and important corrections to the earlier accounts (including those in my book), revealing a number of connections between Kaufmann and other people in Berlin who were attempting to help Jews. These findings have altered her understanding of how the Kaufmann group operated, and in this new edition she argues that there was not a distinct and independently operating “Kaufmann circle” but rather a wider network of “small alliances of helpers” who were loosely connected to Franz Kaufmann. This study therefore broadens our view of the group’s activities beyond the immediate circle around Kaufmann and explores the wider dynamics and patterns of assistance to Jews in wartime Berlin. Rudolph has also examined and corrected discrepancies in some of the postwar accounts, and her book serves as a critical study of how postwar narratives about rescue emerged.

As Rudolph notes in her introduction, however, recent research has yielded new information about the group and important corrections to the earlier accounts (including those in my book), revealing a number of connections between Kaufmann and other people in Berlin who were attempting to help Jews. These findings have altered her understanding of how the Kaufmann group operated, and in this new edition she argues that there was not a distinct and independently operating “Kaufmann circle” but rather a wider network of “small alliances of helpers” who were loosely connected to Franz Kaufmann. This study therefore broadens our view of the group’s activities beyond the immediate circle around Kaufmann and explores the wider dynamics and patterns of assistance to Jews in wartime Berlin. Rudolph has also examined and corrected discrepancies in some of the postwar accounts, and her book serves as a critical study of how postwar narratives about rescue emerged. Three themes run through these sermons: the seriousness of Bonhoeffer’s Christianity, the insight of his responses to the social and political crises of the late Weimar and Nazi eras, and the resolution of his engagement in the Kirchenkampf (German Church Struggle).

Three themes run through these sermons: the seriousness of Bonhoeffer’s Christianity, the insight of his responses to the social and political crises of the late Weimar and Nazi eras, and the resolution of his engagement in the Kirchenkampf (German Church Struggle). One of the editors of this volume, Manfred Gailus (a member of the editorial board of CCHQ), is a historian known to many or most of us as a prolific author and editor of books on Protestant churches in Nazi Germany. These include his Protestantismus und Nationalsozialismus: Studien zur Nationalsozialistischen Durchdringung des Sozialmilieus Berlin (Berlin, 2001), plus books such as Mir aber zerriss es das Herz: Der stille Widerstand der Elisabeth Schmitz (Göttingen, 2010), and Friedrich Weissler: Ein Jurist und bekennender Christ im Widerstand gegen Hitler (Göttingen, 2017). He also has co-edited books with colleagues, such as Nationalprotestantische Mentalitäten in Deutschland—1870-1970 (Göttingen, 2005), co-edited with Harmut Lehmann; Zerstrittene “Volksgemeinschaft:” Glaube, Konfession und Religion im Nationalsozialismus (Göttingen, 2011), co-edited with Armin Nolzen; as well as this volume co-edited with Clemens Vollnhals.

One of the editors of this volume, Manfred Gailus (a member of the editorial board of CCHQ), is a historian known to many or most of us as a prolific author and editor of books on Protestant churches in Nazi Germany. These include his Protestantismus und Nationalsozialismus: Studien zur Nationalsozialistischen Durchdringung des Sozialmilieus Berlin (Berlin, 2001), plus books such as Mir aber zerriss es das Herz: Der stille Widerstand der Elisabeth Schmitz (Göttingen, 2010), and Friedrich Weissler: Ein Jurist und bekennender Christ im Widerstand gegen Hitler (Göttingen, 2017). He also has co-edited books with colleagues, such as Nationalprotestantische Mentalitäten in Deutschland—1870-1970 (Göttingen, 2005), co-edited with Harmut Lehmann; Zerstrittene “Volksgemeinschaft:” Glaube, Konfession und Religion im Nationalsozialismus (Göttingen, 2011), co-edited with Armin Nolzen; as well as this volume co-edited with Clemens Vollnhals. Grünzig’s central question is about a building. What was the place of Potsdam’s Garrison Church in twentieth-century Germany? His answer is striking and sobering. Over a fifty-year period, the Garrison Church was the site of nationalist, National Socialist, military, and militaristic activity. Members of the congregation from Imperial Germany to the last days of Hitler’s regime loudly supported those causes, and the Protestant clergy, many of them military chaplains or veterans, promoted them from the pulpit. The church building was the site of memorials, rallies, processions, and ceremonies—to commemorate the Battle of Sedan, to mourn ten years since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, to honor the anniversary of the death of Friedrich II, and to bless the banners of the Hitler Youth. It was both a symbol of an aggressive Fatherland and itself a force in creating and empowering that version of Germany.

Grünzig’s central question is about a building. What was the place of Potsdam’s Garrison Church in twentieth-century Germany? His answer is striking and sobering. Over a fifty-year period, the Garrison Church was the site of nationalist, National Socialist, military, and militaristic activity. Members of the congregation from Imperial Germany to the last days of Hitler’s regime loudly supported those causes, and the Protestant clergy, many of them military chaplains or veterans, promoted them from the pulpit. The church building was the site of memorials, rallies, processions, and ceremonies—to commemorate the Battle of Sedan, to mourn ten years since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, to honor the anniversary of the death of Friedrich II, and to bless the banners of the Hitler Youth. It was both a symbol of an aggressive Fatherland and itself a force in creating and empowering that version of Germany. In her introductory chapter, Barnett begins with three italicized paragraphs in which she locates her reading of Bonhoeffer’s “After Ten Years.” On the one hand, she notes, “one must be cautious about drawing simplistic historical analogies,” especially with respect to Hitler, Nazism, and the Holocaust. “Nationalism, antisemitism, ethnocentrism, and populism have played a role in different historical periods and national contexts” (1). The grievances and resentments associated with these political movements always emerge out of specific social and cultural contexts. What is left unwritten is that the United States—indeed, the wider Western world—is currently threatened by the resurgence of just these sorts of antagonisms. Barnett continues, noting how important it is that citizens and institutions respond to such threats. Toleration of or compromise with ideologies of hatred will undermine and even destroy Western liberal political cultures. She suggests that this is a very real danger, given the fragility of ethical veneers and social conventions. Living in a time when accepted values and political norms are upended creates crises for individuals, religious bodies, and institutions of civil society, all of which struggle to adapt to or resist to these challenges. Barnett explains that these are the themes Bonhoeffer was addressing in his famous essay. As she writes, “his observations about what happens to human decency and courage when a political culture disintegrates continue to resonate around the world today” (2). This “introduction to the introduction” is very important, because it connects Bonhoeffer’s reflections about Nazi Germany to the upheaval of contemporary politics in the Age of Trump, even as it recognizes that this connection must take place in thoughtful, nuanced ways.

In her introductory chapter, Barnett begins with three italicized paragraphs in which she locates her reading of Bonhoeffer’s “After Ten Years.” On the one hand, she notes, “one must be cautious about drawing simplistic historical analogies,” especially with respect to Hitler, Nazism, and the Holocaust. “Nationalism, antisemitism, ethnocentrism, and populism have played a role in different historical periods and national contexts” (1). The grievances and resentments associated with these political movements always emerge out of specific social and cultural contexts. What is left unwritten is that the United States—indeed, the wider Western world—is currently threatened by the resurgence of just these sorts of antagonisms. Barnett continues, noting how important it is that citizens and institutions respond to such threats. Toleration of or compromise with ideologies of hatred will undermine and even destroy Western liberal political cultures. She suggests that this is a very real danger, given the fragility of ethical veneers and social conventions. Living in a time when accepted values and political norms are upended creates crises for individuals, religious bodies, and institutions of civil society, all of which struggle to adapt to or resist to these challenges. Barnett explains that these are the themes Bonhoeffer was addressing in his famous essay. As she writes, “his observations about what happens to human decency and courage when a political culture disintegrates continue to resonate around the world today” (2). This “introduction to the introduction” is very important, because it connects Bonhoeffer’s reflections about Nazi Germany to the upheaval of contemporary politics in the Age of Trump, even as it recognizes that this connection must take place in thoughtful, nuanced ways. As the second subtitle reveals (“an annotated documentation”), the book is a descriptive representation of the German Christian Church Movement with a regional focus on the origins of the movement in the Wieratal near the city Altenburg. In his presentation, the author outlines the development chronologically: first of all, he describes how the two young vicars, Siegfried Leffler and Julius Leutheuser, who were inspired by National Socialism, began scouring for a small circle of like-minded people from 1927 onwards. Within a few years, this small circle was to become one of the most influential inner-church movements that controlled several Protestant churches during the time of the “Third Reich”. The theological worldview of the church movement was a symbiosis of (Protestant) Christianity and National Socialism, since they saw the direct action of God in Adolf Hitler and his movement.

As the second subtitle reveals (“an annotated documentation”), the book is a descriptive representation of the German Christian Church Movement with a regional focus on the origins of the movement in the Wieratal near the city Altenburg. In his presentation, the author outlines the development chronologically: first of all, he describes how the two young vicars, Siegfried Leffler and Julius Leutheuser, who were inspired by National Socialism, began scouring for a small circle of like-minded people from 1927 onwards. Within a few years, this small circle was to become one of the most influential inner-church movements that controlled several Protestant churches during the time of the “Third Reich”. The theological worldview of the church movement was a symbiosis of (Protestant) Christianity and National Socialism, since they saw the direct action of God in Adolf Hitler and his movement. Come Before Winter begins by acknowledging the memoirs and writings of Sefton Delmer, Otto John, Sigismund Payne Best, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer as sources. It then asserts that “one of the tragedies of World War II was the refusal of President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill to acknowledge the existence of a German resistance,” introducing the failed assassination attempt of July 20, 1944. From there viewers are introduced to Sefton Delmer, the British journalist (born and raised in Berlin) who operated several so-called black propaganda operations, broadcasting disinformation into Nazi Germany. The operation covered by the film was the German short-wave broadcast “Atlantic,” which used a powerful transmitter to broadcast jazz, invented personal announcements, and fake news throughout Germany and also to U-boats in the Atlantic during the later war years. Delmer’s goal was to demoralize German troops and to turn the German public against the Nazis. At several points in the film, broadcasts written by Delmer and Fleming (with information from Otto John) and read by Bernelle are re-enacted, in order to depict Delmer’s determined effort to use propaganda to defeat Germany. These scenes also serve as a vehicle for Otto John, a member of the July 20 assassination plot who had escaped to England, to explain the various efforts of the German Resistance to assassinate Adolf Hitler, along with Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s principled participation in the Resistance and his consequent arrest and detention in Tegel prison.

Come Before Winter begins by acknowledging the memoirs and writings of Sefton Delmer, Otto John, Sigismund Payne Best, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer as sources. It then asserts that “one of the tragedies of World War II was the refusal of President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill to acknowledge the existence of a German resistance,” introducing the failed assassination attempt of July 20, 1944. From there viewers are introduced to Sefton Delmer, the British journalist (born and raised in Berlin) who operated several so-called black propaganda operations, broadcasting disinformation into Nazi Germany. The operation covered by the film was the German short-wave broadcast “Atlantic,” which used a powerful transmitter to broadcast jazz, invented personal announcements, and fake news throughout Germany and also to U-boats in the Atlantic during the later war years. Delmer’s goal was to demoralize German troops and to turn the German public against the Nazis. At several points in the film, broadcasts written by Delmer and Fleming (with information from Otto John) and read by Bernelle are re-enacted, in order to depict Delmer’s determined effort to use propaganda to defeat Germany. These scenes also serve as a vehicle for Otto John, a member of the July 20 assassination plot who had escaped to England, to explain the various efforts of the German Resistance to assassinate Adolf Hitler, along with Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s principled participation in the Resistance and his consequent arrest and detention in Tegel prison.