Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 26, Number 1/2 (June 2020)

Review of Benjamin Ziemann, Martin Niemöller. Ein Leben in Opposition (Munich: DVA, 2019). 640 pages. ISBN: 978-3-421-04712-0.

By Hansjörg Buss, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen; translated by Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

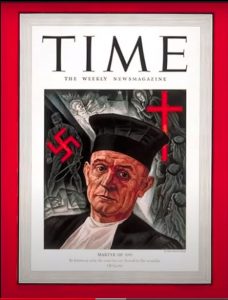

At Christmas 1940, Martin Niemöller appeared on the front page of Time Magazine as the “Martyr of 1940.” Since that same autumn, the film Pastor Hall, inspired by a drama by the playwright Ernst Toller, had been showing in American cinemas. It captured the story of the “Church Struggle” in Germany on celluloid, with little attempt to conceal Niemöller’s biographical details. Since his arrest in the summer of 1937 and subsequent transfer to Sachsenhausen concentration camp on the personal orders of Adolf Hitler, Niemöller had become a worldwide symbol of church resistance to the National Socialist dictatorship. Interest in his person continued even after his liberation at the beginning of May 1945. Despite the irritation that Niemöller provoked by making nationalistic statements in his first public postwar interview, he and his wife travelled to the United States for several months in 1946 and 1947, where he gave over 200 public lectures in 22 states.

To this day, Martin Niemöller remains one of the most famous German churchmen of the twentieth century. He is regarded as an upright resistance fighter against Hitler, who testified to his stance with seven years of incarceration in concentration camps, as a preacher who admonished German “guilt” and as someone who had transformed from an imperial submarine commander of the First World War into a pacifist, who during the 1950s eloquently and powerfully opposed the Federal Republic of Germany’s Western alliance, its remilitarization, and nuclear weapons. Now, 35 years after Niemöller’s death in 1984, Benjamin Ziemann, Professor of Modern German History at the University of Sheffield and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, cuts through the thicket of legend concerning Niemöller’s story and uncovers important strands of his life.

To this day, Martin Niemöller remains one of the most famous German churchmen of the twentieth century. He is regarded as an upright resistance fighter against Hitler, who testified to his stance with seven years of incarceration in concentration camps, as a preacher who admonished German “guilt” and as someone who had transformed from an imperial submarine commander of the First World War into a pacifist, who during the 1950s eloquently and powerfully opposed the Federal Republic of Germany’s Western alliance, its remilitarization, and nuclear weapons. Now, 35 years after Niemöller’s death in 1984, Benjamin Ziemann, Professor of Modern German History at the University of Sheffield and Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, cuts through the thicket of legend concerning Niemöller’s story and uncovers important strands of his life.

Born in 1892, Niemöller came from the home of a Westphalian pastor and chose the career of naval officer. Caught up in the national Protestantism of his time, he experienced the German defeat in the First World War as nothing less than a catastrophe. Only then did he decide to study theology, which he successfully completed in Münster. The book chapter on the völkisch and German national “student politician” is one of the most striking. Niemöller belonged to various far-right parties and associations such as the antisemitic German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation (Deutschvölkischen Schutz- und Trutzbund) and the National Association of German Officers (Nationalverband Deutscher Offiziere) and counted himself among the enemies of Weimar democracy. He also personally held, as Ziemann comprehensively proves for the first time, an aggressive attitude of racial antisemitism. As a father of several children and with his entry into civilian professional life, Niemöller became more moderate in the second half of the 1930s, but initially his political stance did not change. In 1931, after seven years as the organizer of the Westphalian Inner Mission, he moved to Dahlem, a well-to-do parish in Berlin’s southwest. Like many German nationalist pastors of his generation, Niemöller welcomed Hitler’s chancellorship, the “Third Reich,” and the emergence of a “people’s community” (Volksgemeinschaft) founded on Christianity.

Those disputes, which are treated today under the term “church struggle,” were crucial tests. As head of the Pastors’ Emergency League, founded in mid-September 1933, Niemöller became one of its most important protagonists in the second half of 1933 and gained importance throughout the Reich. Ziemann expertly describes the activities of Niemöller in the conflicts of the “church struggle,” accompanied by ecclesiastical, political, and personal tensions and breaks, and ascribes to him a key role in the debates of the Confessing Church concerning the inevitable consequences of Barmen Theological Declaration of the end of May 1934. He experienced the February 1936 division of the Confessing Church into a Dahlemite wing led by Councils of Brethren and a Lutheran wing led by regional bishops not only as a loss, but also as an opportunity for the (Confessing) Church.

His involvement, which led him to become increasingly opposed to the Nazi state and the growing state pressure on the church, ended abruptly on July 1, 1937, with his arrest. After a comparatively mild judgment by the Special Court at the regional court level, which would actually have resulted in his release, he was transferred directly to the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. In the detailed description of his concentration camp imprisonment in the almost fifty-page chapter on Niemöller’s time of suffering as the “personal prisoner of the Führer,” two themes stand out. One was the almost-two-year deliberation about conversion to the Catholic Church, which he only finally decided against at the urging of his wife, in February 1941, a few months before his transfer to Dachau. The other was the “empathy for communists and other victims of Nazi terror,” which Ziemann exposes as a subsequent self-stylization of the postwar period. Rather, he demonstrates an ongoing anti-Bolshevik and nationalist stance: “Even at the moment of liberation from the concentration camp, he interpreted the defeat of the German nation as the fall of the West” (p. 356).

Up to the 1970s, Niemöller remained a public figure and a noticeable and by no means uncontroversial voice in the social debates of the early Federal Republic. Ziemann goes into great detail about Niemöller’s disappointment at the development of the postwar Protestant Church, which he accused of episcopal and confessional tendencies and of supporting Konrad Adenauer’s policies, which he characterized as restorationist. Rooted in his understanding of a “prophetic guardian role” for the church, this went hand in hand with his keen criticism of the founding of the Federal Republic (“conceived in Rome and born in Washington”), the decision to ally with the West, and West German rearmament. Biographically, Niemöller’s sharpest break occurred at the end of the 1950s over the question of war and peace. Under the impact of the destructive force of hydrogen bombs, the former naval officer—who, despite his pacifist criticism of politics and the West German military, felt committed to the ethos of an officer throughout his life—became the most outspoken leader of the West German peace movement, in the campaign “Fight Against Nuclear Death” (“Kampf dem Atomtod”) and after 1957 as president the German Peace Society (Deutsche Friedensgesellschaft). Only then did Niemöller’s Protestant nationalist guiding principles wear off, which in the immediate postwar period were still expressed in nationalist speeches and manifest in his participation in the mythology of German victimhood. Ziemann’s portrait of the post-war Niemöller is extremely multifaceted, describing how Niemöller, increasingly shaped by international and ecumenical concerns, dramatically shifted his stance toward the church and underwent a political transformation.. Ziemann, however, does not lose sight of the continuities: Niemoller’s persistent unease (which he never completely abandoned) with representative party democracy and media diversity , his latent anti-Catholicism and anti-Americanism, as well as his persistent culturally and socially fueled antisemitic resentment.

Anyone interested in Martin Niemoeller’s eventful life cannot ignore Ziemann’s extremely rich, brilliantly written, critical, yet balanced account. In the controversial and polarizing person of Niemoller—the “volcano” Niemöller, as the Bishop of Württemberg Theophil Wurm once put it—he also depicts the fundamental conflicts that marked the four political systems of the late empire, the unpopular and defeated Weimar Republic, the National Socialist ideological dictatorship, and the Federal Republic, which was in search of new ways forward. Using the example of the “belated” pastor, the “church fighter” (“Kirchenkämpfer”), the church president of the postwar Hesse-Nassau Regional Church, and the internationally-recognized ecumenist, Ziemann also reflects the fundamental upheavals of twentieth-century religious life.

The strength of his biography is also a result of the fact that he does not stop at the public Martin Niemöller. Without committing any indiscretions, Ziemann writes about the strict “patriarch” and family man; the restless, often overwhelmed and driven worker; the impatient, polemical, and self-opinionated disputant who also offended those who were on his side; and, last but not least, the one who was challenged, who repeatedly suffered severe personal crises. And he writes about Else Niemöller, his wife who died in a car accident in 1961 and with whom Martin had been married for almost forty years. One of Ziemann’s great achievements in his publication is that he acknowledges her role as a discussion partner and advisor, editor of his sermons, emotional support during his term in prison, and, last but not least, as the one who took care of the family during Niemöller’s extremely time-consuming activities as an organizer of the Inner Mission, as a pastor, and as a church politician. Benjamin Ziemann’s Niemöller biography is already a standard work.

This book, edited by Alf Christophersen and Benjamin Ziemann, has given a surprising moment in Niemöller’s life its most thorough explication. It also offers readers an edited version of the handwritten manuscript Niemöller produced within a period of less than three months during his four years of solitary confinement in Sachsenhausen. His assessment of Catholicism versus Protestantism, a document which numbers over 200 pages in Niemöller’s hand, now comprises 150 printed pages in this book.

This book, edited by Alf Christophersen and Benjamin Ziemann, has given a surprising moment in Niemöller’s life its most thorough explication. It also offers readers an edited version of the handwritten manuscript Niemöller produced within a period of less than three months during his four years of solitary confinement in Sachsenhausen. His assessment of Catholicism versus Protestantism, a document which numbers over 200 pages in Niemöller’s hand, now comprises 150 printed pages in this book. The structure of the book is not unduly distinctive, but it sets out clearly the overall argument and method. Huber’s Bonhoeffer is certainly a big and complex figure. He is also one full of contrasts and the author delights in framing and exploring them. An introductory section evokes the figure of Bonhoeffer as we might first encounter him in a variety of places, not least over the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey. There follows a section on Bonhoeffer’s background and early formation and then another three on his early work in the contexts of university and church life, the first situating him firmly in the landscapes of German thought, the second examining a theology of grace which was deeply rooted in the precepts of Lutheranism, and the third discussing the place of the Bible in a world of maturing historical criticism. Each of these sections present dualities which already defined so much in Bonhoeffer’s work (‘Individual spirituality or Society’; ‘The Church of the World or the Church of the Word’; ‘Acting justly and waiting for God’s own time’; ‘The Historical Jesus or the Jesus of Today’). The young Bonhoeffer is certainly very much at home in the intellectual landscapes of German Lutheranism but the emerging vision is an open one and there is no knowing where it will lead.

The structure of the book is not unduly distinctive, but it sets out clearly the overall argument and method. Huber’s Bonhoeffer is certainly a big and complex figure. He is also one full of contrasts and the author delights in framing and exploring them. An introductory section evokes the figure of Bonhoeffer as we might first encounter him in a variety of places, not least over the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey. There follows a section on Bonhoeffer’s background and early formation and then another three on his early work in the contexts of university and church life, the first situating him firmly in the landscapes of German thought, the second examining a theology of grace which was deeply rooted in the precepts of Lutheranism, and the third discussing the place of the Bible in a world of maturing historical criticism. Each of these sections present dualities which already defined so much in Bonhoeffer’s work (‘Individual spirituality or Society’; ‘The Church of the World or the Church of the Word’; ‘Acting justly and waiting for God’s own time’; ‘The Historical Jesus or the Jesus of Today’). The young Bonhoeffer is certainly very much at home in the intellectual landscapes of German Lutheranism but the emerging vision is an open one and there is no knowing where it will lead. Rebecca Scherf’s study of the German Evangelical Church’s (GEC) responses to the concentration camps is a significant new contribution to the scholarship. While her main focus concerns Protestant clergy who were sent to concentration camps (she confined her study to concentration camps, so it does not include pastors who were in prisons), she has broadened her analysis to address three points of intersection between the GEC and the concentration camp system. The first concerns the relationship between regional churches and the Protestant chaplains who served in the early camps. The second examines the official church responses when clergy were sent to camps. The third looks at the experiences of those who were imprisoned in camps by drawing on contemporary documentation and subsequent memoirs. There are several appendixes with helpful graphs illustrating the number of clergy arrests by year (1935—when there were mass arrests of Confessing pastors due to a pulpit protest—was the peak), by camp, and by regional church. While most clergy who were sent to camps were held only briefly (indicating that the Nazi state intended such arrests as a form of intimidation), the number of arrests during the war grew and fewer were released. There is also a chronologically and geographically organized list of the Protestant clergy who were imprisoned.

Rebecca Scherf’s study of the German Evangelical Church’s (GEC) responses to the concentration camps is a significant new contribution to the scholarship. While her main focus concerns Protestant clergy who were sent to concentration camps (she confined her study to concentration camps, so it does not include pastors who were in prisons), she has broadened her analysis to address three points of intersection between the GEC and the concentration camp system. The first concerns the relationship between regional churches and the Protestant chaplains who served in the early camps. The second examines the official church responses when clergy were sent to camps. The third looks at the experiences of those who were imprisoned in camps by drawing on contemporary documentation and subsequent memoirs. There are several appendixes with helpful graphs illustrating the number of clergy arrests by year (1935—when there were mass arrests of Confessing pastors due to a pulpit protest—was the peak), by camp, and by regional church. While most clergy who were sent to camps were held only briefly (indicating that the Nazi state intended such arrests as a form of intimidation), the number of arrests during the war grew and fewer were released. There is also a chronologically and geographically organized list of the Protestant clergy who were imprisoned. The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration.

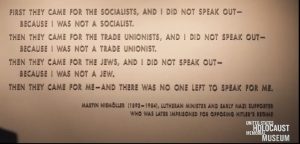

The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration. After remarking on the power, universality, and timelessness of the Niemöller quotation Brown-Fleming explained how Niemöller—though he is often held up as an opponent of Nazism—began as a supporter of the Hitler movement. Born into a monarchic, nationalist home, he served as a naval officer during the First World War and also held the typical antisemitic stereotypes of his day, seeing Jews as the Christ-killers and as outsiders in German society. Niemöller voted for the Nazis in several elections between 1924 and 1933 and read Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf. He resonated with Nazism and believed Hitler could bring God and country together into a powerful union.

After remarking on the power, universality, and timelessness of the Niemöller quotation Brown-Fleming explained how Niemöller—though he is often held up as an opponent of Nazism—began as a supporter of the Hitler movement. Born into a monarchic, nationalist home, he served as a naval officer during the First World War and also held the typical antisemitic stereotypes of his day, seeing Jews as the Christ-killers and as outsiders in German society. Niemöller voted for the Nazis in several elections between 1924 and 1933 and read Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf. He resonated with Nazism and believed Hitler could bring God and country together into a powerful union. Time magazine featured Niemöller on its cover in 1940, as a symbol of the church, which it described as the sole domestic opponent to Nazism. Indeed, as Brown-Fleming explained, people from all around the world prayed for Niemöller and sent letters to him in the concentration camp.

Time magazine featured Niemöller on its cover in 1940, as a symbol of the church, which it described as the sole domestic opponent to Nazism. Indeed, as Brown-Fleming explained, people from all around the world prayed for Niemöller and sent letters to him in the concentration camp.