Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 30, Number 3 (Fall 2024)

Review of Johannes Sachslehner, Hitlers Mann im Vatikan: Bischof Alois Hudal: ein dunkles Kapitel in der Geschichte der Kirche (Graz: Molden Verlag, 2019). ISBN 978-3-222-15040-1.

By Martin Menke, Rivier University

In this work, Johannes Sachslehner, an Austrian historian and prolific author, offers a biography of the Austrian bishop Alois Hudal, notorious for his complicated relationship with National Socialist ideology and for his involvement in the postwar effort to enable refugees and war criminals to escape to South America. The author’s attention to Hudal’s entire lifespan — not only his years at the Pontifical Institute of Santa Maria dell’Anima, better known as “the Anima,” but especially to his formative years in Graz — might have rendered this work a useful contribution to the scholarly literature. Instead, the reader faces a fatally flawed book.

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position.

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position.

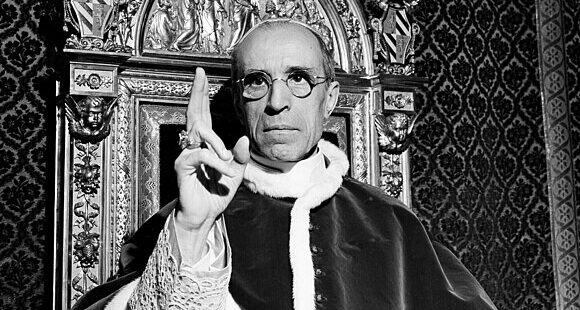

During World War One, Hudal served as a military chaplain in the Habsburg army. He gave rousing sermons in German, Italian, and Slovenian. Soon after the collapse of Austria-Hungary following the war, Hudal began promoting Germany’s cultural mission in Europe and the political hegemony arising from that mission. In 1919, Hudal became a professor of Old Testament Scripture at Graz University and achieved tenure in 1923. The same year, he was appointed coadjutor at the Anima (he took a leave from Graz to pursue this) and became its rector in 1937. In 1934, Hudal seized the opportunity to promote himself by producing a draft concordat with Austria long before either the Austrian government or the Holy See considered such a treaty. Hudal’s contributions to the concordat won him the favor of Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the Cardinal Secretary of State and later Pope Pius XII, at least for a time. His role in placing Alfred Rosenberg’s Mythos des Zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts on the index of forbidden books in 1934 also enhanced his standing in the Vatican. Furthermore, it showed how opposed Hudal initially was to National Socialist ideology.

As Sachslehner shows, Hudal suffered humiliating career reversals during his early years. Hudal repeatedly attempted to rewrite his biography to erase his working-class roots and Slovenian paternity. In 1923, Cologne’s Archbishop Cardinal Karl-Joseph Schulte, who wanted to end Austrian leadership of the German-speaking community in Rome, strongly opposed Hudal’s appointment as Coadjutor of the Collegio Teutonico di Santa Maria dell’Anima, the German seminary in Rome. Fully expecting to be ordained Archbishop of Vienna upon the death of Cardinal Friedrich Gustav Piffl in 1932, Hudal ordered a bishop’s crozier. Ultimately, he had to wait a year before his ordination as titular bishop of Aela without a proper diocese. Furthermore, as World War Two ended, Hudal began emphasizing his Austrian heritage and his critiques of National Socialism. He sought good relations with the Allies in Rome and elsewhere. Sachslehner also shows Hudal’s exaggerated self-importance, shown when he sent memoranda to Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin on a possible post-war Danubian confederation.

Later, Hudal nurtured plans for a new university chair in Vienna dedicated to the study of the Eastern churches, which he intended to fill himself. This also did not come to pass. These details confirm what other scholars have written about Hudal’s most active years, and Sachslehner puts these activities within the broader contexts of Hudal’s life.

Once Hudal became rector of the Anima, in spite of the opposition of Cardinal Schulte and with the support of the Austrian government, he tried to emphasize the Anima’s all-German identity. Like many Germans and Austrians, Hudal rejected the outcome of World War One. Hudal did not seek, however, the restoration of the Austro-Hungarian multi-ethnic empire, nor did he seek, at the time, the Anschluss (the unification of Austria and Germany). He imagined Austria’s future as a strong, independent state. Furthermore, Sachslehner shows that, throughout his life, Hudal still ranked commitment to the church and faith above his commitment to the German nation. As others have shown, Hudal’s views on National Socialism changed over time. Sachslehner contributes a differentiated view of these changes. Hudal rejected National Socialism’s desire to replace faith in Christianity with racial faith, but he embraced antisemitism and ethnic prejudice. His antisemitism stemmed from his formative years in Graz. In 1919, he blamed Austria-Hungary’s defeat on the “Jewish Bolshevik [Karl] Kautsky.” Hudal always associated communism with Judaism. Sachslehner argues that Hudal’s desire for recognition fed his increasingly close ties to National Socialism. In 1937, the same year he became rector of the Anima, he published Grundlagen des Nationalsozialismus, seeking to build a bridge between the Church and National Socialism. He argued that only German culture could guarantee the continuation of Christian values in Europe. The work showed that Hudal completely misunderstood the National Socialists’ intentions and overestimated his own importance. The changes in National Socialist ideology that Hudal considered necessary and possible were, in fact, unimaginable. The Grundlagen sapped much of Hudal’s support in the Vatican curia, and after the 1938 Anschluss, which Hudal had promoted, he lost all favor with Pacelli (the future Pius XII). Pacelli forbade Hudal from celebrating a Te Deum thanksgiving service for the Anschluss. While many historians have focused on Hudal’s work enabling hunted war criminals to escape, Sachslehner shows that these pre-war events marked the beginning of Hudal’s downfall.

The story of Hudal’s wartime and post-war activities is well known. Working with archival records from the Anima made available in 2006, Sachslehner offers some useful corrections to the most extreme accusations leveled against Hudal. For example, during the German occupation of Rome, Hudal hid both hunted Germans and Austrians (such as conservatives who had been safe in fascist Italy, such as the German army officer Bernhard Schilling [161]) and Allied soldiers in the Anima. During the 1943 raids against Roman Jews, German diplomats asked Hudal to send a letter to the German Commandant of Rome, Major General Rainer Stahel. Written at the clandestine prompting of German embassy officials, it was intended to hasten end of the raids. (159) Because of bureaucratic delays, the letter reached Berlin when the raids had all but ended. It should be noted here that, while Sachslehner cites his source, Rom 1943-1944 by Robert Katz, the citation is incomplete (the complete title is Rom, 1943-1944: Besatzer, Befreier, Partisanen und der Papst [Essen, 2006]), and Sachslehner does not list this volume in the bibliography. Sachslehner notes that Hudal was “not particularly proud” of the letter and quotes Hudal’s secretary, Joseph Prader, who claimed, “Hudal absolutely hated Jews.” (159) Sachslehner points out that, after the war, he did help known war criminals escape but was not responsible for the escape of Adolf Eichmann. Hudal abused his ties to Austria in order to provide false documents for these criminals. Hudal seemed to see no contradiction between hiding anti-fascists during the war and helping fascists escape after the war. To him, they were all persecuted Christian victims deserving of Christian charity. In Rome, Hudal sought to maintain control of the Austrian community. Suddenly, he supported Austrian independence and claimed to represent Austrian interests when dealing with Allied officials in Rome. There is some evidence that Hudal acted as a paid informant for U.S. military counterintelligence services. As in so many cases from this period, a strident anti-Communism made up for Hudal’s previous fascist leanings.

Sachslehner again points to Hudal’s need for recognition as a driving force for his post-war actions, which occurred after he had lost Vatican support and his academic position at Graz, for which he had been paid during his entire lengthy absence. By the early 1950s, his continued presence at the Anima proved an embarrassment to Church officials, who forced him from office, which left him embittered.

Sachslehner provided no evidence that Hudal ever admitted the contradictions in his life, even to himself.

Sachslehner’s argument about and analysis of Hudal’s early life are persuasive. Some scholarly concerns about the work remain. The citations of archival materials lack detail. In some cases, only box numbers are mentioned. In others, even box numbers are missing. Sachslehner includes some questionable works among his cited sources, such as Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s The Catholic Church and the Holocaust and the judgment of a German neo-Nazi. Even if he critiques their judgment, why include them at all in his review of the literature? Hudal’s views and actions justly led to his condemnation by less controversial scholars. Even so, Sachslehner’s contribution to scholarship on this subject might have been his emphasis on what one might consider Hudal’s inferiority complex about his origins and certainly on his ambition and need for recognition as motives for his views and actions. But do they change the field’s judgment of Hudal’s role in this dark chapter of history? Not significantly. Worse, there is good reason to believe that academic dishonesty undermines any value of this work.

Given the problematic use of the Katz volume mentioned above, it is not surprising that other reviewers have found additional scholarly problems. A fellow editor directed this reviewer to a lengthy review of Sachslehner’s work by Austrian historian Dirk Schuster[i], who found a number of problematic passages. Conducting further research, Schuster found an uncanny resemblance between passages in Sachslehner’s volume and the unpublished dissertation of Markus Langer, entitled “Alois Hudal: Zwischen Kreuz und Hakenkreuz: Versuch einer Biographie,” submitted in 1995.[ii] First, the chapter and sub-chapter titles in Sachslehner vary very little from those of Langer.[iii] Second, according to Schuster, there are passages in Sachslehner’s work that are simple paraphrases of Langer’s work.[iv] While Sachslehner mentions some of Langer’s work in the endnotes (for example, endnote 148), he omits the title and any additional information, and he omits Langer’s work entirely from the bibliography.

In the case of another scholar’s work, Schuster accuses Sachslehner of plagiarism. Schuster shows that Sachslehner copied verbatim several text passages from the work of Hansjakob Stehle in Die Zeit.[v] While Sachslehner mentions several works by Stehle in his endnotes and bibliography, he does not identify them as quotations. Schuster also mentions other problems concerning inaccurate citations. Simply put, with his name on the book, Sachslehner claims credit for scholarly research that he never conducted. This renders the work unreliable and the author’s conduct unethical.

Thus, we will continue to wait for an authoritative biography of Alois Hudal to appear. As Thomas Brechenmacher points out, Hudal offers much more scope for research than what has been published up to this point.[vi]

Notes:

[i] Dirk Schuster, “Sachslehner, Johannes: Bischof Alois Hudal. Hitlers Mann im Vatikan. Ein dunkles Kapitel in der Geschichte der Kirche “ In Religion in Austria 6 (2021), 395-411.

[ii] Schuster, 396.

[iii] Schuster, 400.

[iv] Schuster, 402.

[v] Hansjakob Stehle, “Pässe vom Papst? Aus neuentdeckten Dokumenten: Warum alle Wege der Ex-Nazis über Rom nach Südamerika führten.” Die Zeit, 4 May 1984, 9-12, discussed in Schuster, 403-407.

[vi] Thomas Brechenmacher Alois Hudal – der „braune Bischof“? In: Freiburger Rundbrief. Nr. 2 14, 2007, ISSN 0344-1385, S. 130–132.

Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true.

Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true.

Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background.

Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background. Helge-Fabien Hertz’s weighty dissertation (2021) from Kiel University, supervised by Rainer Hering (Schleswig- Holstein State Archives), Peter Graeff and Manfred Hanisch (both from Kiel University), now joins this recent research tradition. The study consists of a group biography of the 729 pastors who worked in the Schleswig-Holstein state church shortly before and during the Nazi era (1930-1945). The study is based on a broad range of sources: the clergymen’s personal files were evaluated; in addition, the author has consulted sermons and confirmation lesson plans, denazification files, the relevant state church archive files on the Kirchenkampf, documents on NSDAP membership in the Berlin Federal Archives, and a wealth of contemporary lectures, articles, letters, diaries. Hertz uses a sophisticated set of social-science methods to operationalize the exorbitant amount of data from this large group of people (quantification of “attitudes” and “actions” with the aid of indicators) and to present it using a variety of statistics, diagrams, etc. One must admit at the outset, it is not always easy to keep track of the whole given the extreme complexity of the work’s organization into “parts”, “sections”, “chapters”, and so on.

Helge-Fabien Hertz’s weighty dissertation (2021) from Kiel University, supervised by Rainer Hering (Schleswig- Holstein State Archives), Peter Graeff and Manfred Hanisch (both from Kiel University), now joins this recent research tradition. The study consists of a group biography of the 729 pastors who worked in the Schleswig-Holstein state church shortly before and during the Nazi era (1930-1945). The study is based on a broad range of sources: the clergymen’s personal files were evaluated; in addition, the author has consulted sermons and confirmation lesson plans, denazification files, the relevant state church archive files on the Kirchenkampf, documents on NSDAP membership in the Berlin Federal Archives, and a wealth of contemporary lectures, articles, letters, diaries. Hertz uses a sophisticated set of social-science methods to operationalize the exorbitant amount of data from this large group of people (quantification of “attitudes” and “actions” with the aid of indicators) and to present it using a variety of statistics, diagrams, etc. One must admit at the outset, it is not always easy to keep track of the whole given the extreme complexity of the work’s organization into “parts”, “sections”, “chapters”, and so on.