Review of Josef Meyer zu Schlochten and Johannes W. Vutz, eds., Lorenz Jaeger: Ein Erzbischof in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus

Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 29, Number 1/2 (Summer 2023)

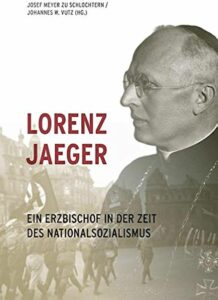

Review of Josef Meyer zu Schlochten and Johannes W. Vutz, eds., Lorenz Jaeger: Ein Erzbischof in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (Münster: Aschendorff, 2020). ISBN 978-3-402-24674-0.

By Martin Menke, Rivier University

By necessity, prominent figures in the first three decades of the Federal Republic’s existence had experienced the Third Reich as young or middle-aged adults. Many of those in responsible roles during the Third Reich hid or minimized their involvement with the regime. Beginning with the revelations concerning Heinrich Globke, close aid to Chancellor Adenauer, the pasts of prominent figures came to light. Often, those responsible for such disclosures aimed to embarrass and damage the reputation of those concerned. A particular target for some were the leaders of the Christian churches in Germany, most of whose careers had begun long before 1945. Among historians, revelations of past mistakes and crimes have evolved from sensational efforts to discredit certain figures to reviewing individual biographies as part of Germany’s broader coming to terms with its past, its Vergangenheitsbewältigung. Most recently, perhaps with the benefit of distance, more methodologically sound, less agenda-driven scholarship is occurring. In this historiographical evolution, the history of the churches during the Third Reich occurred early. Unlike most attacks on leading political and cultural figures, the attacks on the Churches were often aimed at the institutions themselves. Recent scholarship on Catholic resisters, on Catholics who became National Socialists, and on members of the German hierarchy (Berning, Jaeger, Frings, Gröber, and Bertram, for example) reveals that this trend to broader history-writing is complicated by the different biographies of the historical subjects.

In the volume under review, the contributions of different generations of historians reflect this evolution. The subject is Cardinal Lorenz Jaeger, Archbishop of Paderborn, 1941-1973. Before becoming archbishop, Jaeger had served as a regular army officer in World War One, then entered the seminary. He served as Dortmund’s youth pastor and teacher during the inter-war period. Upon the outbreak of World War II, Jaeger immediately volunteered as a military chaplain. Both in his capacity as a teacher and as a military chaplain, he had to pass background checks by Nazi authorities. Various contributors, however, note that, during Jaeger’s episcopal ordination process, the regime’s security authorities reported fundamental misgivings about his appointment. As early as 1935, authorities noted his rejection of Alfred Rosenberg’s Mythos des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. The Sicherheitsdienst [SD] and regional NSDAP offices considered him a threat to the regime. At the ministerial level, both sides tried to de-escalate conflicts in the broader context of the regime’s relations with the Catholic Church, especially in episcopal ordinations. So the Reich Minister of Church Affairs, Hans Kerrl, approved Jaeger’s ordination as Archbishop of Paderborn.

In the volume under review, the contributions of different generations of historians reflect this evolution. The subject is Cardinal Lorenz Jaeger, Archbishop of Paderborn, 1941-1973. Before becoming archbishop, Jaeger had served as a regular army officer in World War One, then entered the seminary. He served as Dortmund’s youth pastor and teacher during the inter-war period. Upon the outbreak of World War II, Jaeger immediately volunteered as a military chaplain. Both in his capacity as a teacher and as a military chaplain, he had to pass background checks by Nazi authorities. Various contributors, however, note that, during Jaeger’s episcopal ordination process, the regime’s security authorities reported fundamental misgivings about his appointment. As early as 1935, authorities noted his rejection of Alfred Rosenberg’s Mythos des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. The Sicherheitsdienst [SD] and regional NSDAP offices considered him a threat to the regime. At the ministerial level, both sides tried to de-escalate conflicts in the broader context of the regime’s relations with the Catholic Church, especially in episcopal ordinations. So the Reich Minister of Church Affairs, Hans Kerrl, approved Jaeger’s ordination as Archbishop of Paderborn.

Historians disagree on Jaeger’s affinity for the Nazi regime before his ordination. Some take his service in World War One, his conservative nationalism, his anti-Bolshevism, and his immediate volunteering as a military chaplain as proof of his affinity to the regime. In the volume, several contributors convincingly prove that Jaeger was a nationalist and a conservative who promoted patriotism, opposed the Treaty of Versailles, and believed in the divinely ordained authority of the state. Those same contributors show, however, that Jaeger’s conservatism was akin to that of the resistance leaders against Hitler, such as Stauffenberg and Goerdeler. They also point to Jaeger’s insistence on the primary importance of faith and obedience to God among Catholic youth. Jaeger was a convinced Catholic and a proud German. Some contributors argue that one needs to understand the sensibilities of the times rather than judge Jaeger with presentist attitudes. These contributors argue that contemporary historians lack an awareness of how the times limited a priest or bishop’s freedom of action during the Nazi era. Others pointed out that Jaeger, like many bishops, adopted the idiom of the Third Reich without intending to convey the same racist message as the regime did. While Jaeger visited Israel and Jordan in 1964, there is no evidence of any statements by Jaeger concerning antisemitism and the Shoah. In the volume, the question of Jaeger’s own view of Jews and of the regime’s persecution largely goes unmentioned. This raises the question of whether there is no evidence to be found or if seemed irrelevant or, worse, unpalatable to the authors and editors?

The volume’s purpose and genesis pose questions of scholarly independence. Overall, the volume primarily consists of contributions defending Jaeger by pointing out his disagreements with the regime, his insistence on the Church’s role in forming young minds, and his ministrations to his archdiocesan flock despite all harassment and persecution by the regime. Given the volume’s creation circumstances, one would have hoped for additional critical voices. The book is the result of research commissioned by the archbishop of Paderborn in 2015, designed to respond to a civic petition to revoke Jaeger’s honorary citizenship in the city. The archbishop commissioned the Theologische Fakultät Paderborn, not the city’s university or the Katholische Hochschule Nordrhein-Westphalen at Paderborn.

Given that the Archdiocese sponsors the Theologische Fakultät, more independent voices would have been welcome. Nonetheless, several authors in the study note mistakes, poorly chosen language, ambiguous statements, and more to question the narrative of a staunchly anti-National Socialist bishop. In the discussions of Jaeger’s postwar tenure, the contributors are more willing to admit his shortcomings and blind spots. For example, Jaeger found it extremely difficult to contend with the radical changes in Germany, North-Rhine-Westphalia, and within the Church in the sixties and early seventies. Demands for greater lay participation, especially in denominational public schools, and for greater moral freedom in sexual morality challenged Jaeger, contributing to his resignation in 1973.

Jaeger’s most vigorous opponent was Rudolf Augstein, publisher of the influential post-war periodical Der Spiegel. In 1965, the journal launched a full-fledged attack on Jaeger. Der Spiegel claimed that, as a military chaplain and archbishop who “got along” with the Nazi regime, Jaeger had forfeited the moral legitimacy of his office. Der Spiegel based its criticism on Guenter Lewy’s The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany, which was published in German in 1965. Lewy’s work included several erroneous interpretations of his sources, including one about a sermon by Jaeger. Der Spiegel made this false interpretation the basis of an article seeking to undermine Jaeger. Jaeger’s attorneys achieved a clarification by Der Spiegel and changes to Lewy’s manuscript by the German publisher. In the 1973 elections, Augstein again published critiques of Jaeger’s past during the Third Reich. However, the publisher received support neither from the left-wing political parties nor from any other news media.

Several contributors argue that the criticism of Jaeger’s position in the sixties and early seventies colored historians’ analysis of his actions during the Nazi period. On the other hand, other historians, foremost Joachim Kuropka, refuse to acknowledge any mistakes or missteps on Jaeger’s part during the Nazi period or later. Kuropka, in particular, succeeds in undermining the arguments of Jaeger’s most ardent critics, Wolfgang Stüken und Peter Bürger, by dissecting their analysis of the archival evidence. Unfortunately, Kuropka undermines the effectiveness of his fight with unnecessary polemics against Jaeger’s critics. Fortunately, the volume’s final essay by Dietmar Klemke offers scholars an honest analysis of Jaeger’s achievements. Klemke points out both moments in which Jaeger resolutely contradicted the Nazi regime and those in which Jaeger fell short of the expectations one might have of a Catholic bishop. Klemke argues that Jaeger should have known that opposition to bolshevism does not necessitate the support of the Nazi regime. Ultimately, Klemke argues that Jaeger belongs in a gray zone of individuals whose actions and attitudes during the National Socialist period are ambiguous.

This description seems an accurate assessment of clergy from Pius XII to many a parish priest and lay Catholic. There are those, such as the “brown priests” whom Kevin Spicer has identified, or Alfred Delp, who resisted the Nazi regime while insisting on Germany’s profound cultural mission. Catholic individuals like Jaeger, Delp, Galen, and many others find approval for their criticism of and sacrifice against the Nazi regime while beholden to patriotic, nationalist, and religious values that make them seem less than heroic in our age.

While the purpose of this volume was to intervene in the Paderborn city council’s decision on whether or not to repeal Jaeger’s honorary town citizenship, the emphasis on Jaeger’s early encouragement of ecumenicism and his role in including an opening to ecumenicism in the decisions of Vatican II, discussed in the essays by Detlef Grothmann and Dina von Fassen, and by Klemke, bears further research. Similarly, Grothmann and von Fassen noted that Jaeger’s activities concerning the diocesan territories in the Soviet zone of occupation bear further investigation.