Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 22, Number 3 (September 2016)

Conference Report: “Not Without the Old Testament”: The Importance of the Hebrew Bible for Christianity and Judaism, French Church of Friedrichstadt, Berlin, 8-10 December 2015

By Gerhard Naber, Nordhorn, and Oliver Arnhold, University of Bielefeld and University of Paderborn; translated by Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

Note: Normally Contemporary Church History Quarterly publishes historical rather than theological material. However, given the relevance of any German theological debate concerning the validity of the Old Testament to the antisemitic history of the German Christian Movement in the Nazi period, it seemed useful to publish this report from a noteworthy conference. The following account demonstrates that the conference “Not Without the Old Testament” grappled not only with contemporary theological problems, but also with the shadow of this history. Translator’s additions appear in square brackets.

Conference organizers: Protestant Academy of Berlin; Moses Mendelssohn Center for European-Jewish Studies; Moses Mendelssohn Foundation; Protestant Church of Berlin, Brandenburg, and Silesian Upper Lusatia; Church and Judaism Institute (Humboldt University).

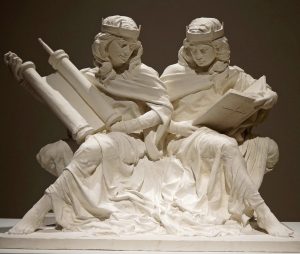

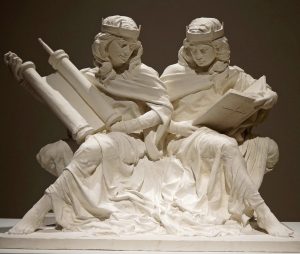

Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time (2015), by Joshua Koffman

On the invitation to this conference and also on the huge display wall at the front side of the French Church of Friedrichstadt, we see two young women with crowns (princesses, perhaps?). They are similarly clothed, level with one another, and facing each other—each of them occupied with a scripture: the left one with a scroll, and the right one with a book marked with a cross—clearly a Torah and a Bible. What is special, however, is that neither looks (only) at her own scripture, but—in this moment—is interested in the scripture of the other.

The picture fascinates and confounds.

Such a composition is well known from medieval imagery. On almost all gothic churches we can find Ecclesia and Synagoga, an image of anti-Jewish theology with the message: Israel has been rejected; the Church has triumphed. But here, both figures are on the same level, made equal. They read their writings, but are also interested in the things that concern the other. This image of dialogue between Israel and the Church, created by Joshua Koffman, is entitled “Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time” (2015).

This representation symbolizes better than any other the protocol for the conference “Not Without the Old Testament.”

The background for this conference was the current, so-called “Slenczka Debate.” In 2013, the Berlin systematic theologian Dr. Notger Slenczka published a treatise in which he expressed concern that it might be time—in the intellectual tradition of Schleiermacher, Harnack, and Bultmann—to decanonize the Old Testament, i.e. perhaps to downgrade it to the status of the Apocrypha and in any case not to grant it the same status as the New Testament for Christian theology and for the Church.

This was certainly impetus enough to fundamentally reexamine the importance of the Old Testament for Christians and the Tanakh [Hebrew Bible] for Jews.

After greetings from Dr. Eva Harasta of the Protestant Academy and Dr. Julius H. Schoeps of the Moses Mendelssohn Center, the first session revolved around the question “Text and Politics.” Dr. Rolf Schieder spoke first on the theme of “The Political Responsibility of Christian Theology towards the Old Testament.” He criticized the fever of the debate, the style of the confrontation. It was important that technical questions be kept at the center. Slenczka’s thesis should therefore be taken seriously, insofar as he sees his position within the realm of Jewish-Christian dialogue. Christians should not worm their way into the covenant with Israel; they should respect the Old Testament as a record of Jewish faith. Finally, the speaker proposed a “dogmatic disarmament”—not to understand the canon as normative, but as a collection of texts for use in worship, teaching, and personal devotion. In this sense, the Old Testament is certainly part of the Christian canon.

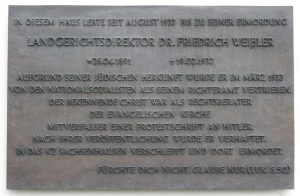

Dr. Oliver Arnhold, Department Head for Protestant Religious Instruction in Detmold and Visiting Lecturer at the Universities of Paderborn and Bielefeld, examined aspects of the “Ecclesiastical and Theological Treatment of the Old Testament among the German Christians (DC).” Arnhold made it clear that the DC were no unified block, and provided various examples of gradations in the question of the status of the Old Testament. On the one hand, Friedrich Wienecke advocated for the maintenance of the Old Testament, while, on the other hand, Reinhold Krause called for a radical separation from the Old Testament and parts of the New Testament at the “Sport Palace Rally” [in Berlin in November 1933].

Arnhold gave a detailed outline of Walter Grundmann’s position in the “28 Theses of the DC”: The Old Testament is not of the same value as the New Testament; rather, it should serve as an example of the failure of the Jewish way (Thesis 12). The abandonment of the Jews by God resulted in the curse of God on this people—up to the present day (Thesis 13). And for his part, Siegfried Leffler, co-founder of the Thuringian Church Movement of the German Christians, wanted to replace the Old Testament with stories from German history.

A key institution for this movement was the “Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life” (“Dejudaizing Institute”), founded [by Grundmann] in 1939 in Eisenach. By 1941, Grundmann had managed to win about 180 associates for the scholarly work of the Institute, including 24 university professors from 14 Protestant theological faculties, along with ecclesiastical dignitaries and emerging scholars. These served voluntarily in working groups, research projects and publishing activities. A total of 46 research projects and workshops aimed to erase Jewish elements from theology and Church, among other things. In place of the Old Testament, personnel in the Grundmann Institute proposed the legends of German heroes and saints as the model and ideal for religious life.

“The Combination of Politics and Theology in the Controversy concerning the Old Testament: A Jewish-Civil Society Perspective”—this was the topic of the evening lecture by the Jewish Education scholar Dr. Micha Brumlik, who went into great detail about the life and thought of the theologian Emanuel Hirsch. Hirsch understood “Volk” as the concrete place, where the message of God is encountered. Thus he became a member of the German Christian Movement out of conviction, and the National Socialist Party too. In 1933 he proclaimed “a YES to the German year!” and praised Hitler “as an instrument of the Lord of all.” The Old Testament served for him as a demonstration of a false, inadequate understanding of God that should crumble. Brumlik pointed out that the line of tradition in which Slenczka stands includes not only Schleiermacher and Harnack, but also theologians like Hirsch, who fawned over National Socialism.

The second day of the conference—Wednesday, December 9, 2015—was devoted to the theme of “Text and Hermeneutic.” It was opened by Dr. Andreas Schüle, Professor of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis at the University of Leipzig, under the title “Bible Minus Old Testament: A Blind Alley.” At the outset he demonstrated that uncertainty arises if faith becomes “questionable” and people insist upon resources of certainty. The Bible is one such resource, but that idea is hard to understand outside of a worship service and outside of church. Along with Niklas Luhmann, Schüle describes the Bible as a “communications medium,” that with its diverse histories, ideas, images, and motifs can be understood in diverse ways and can withstand selective attacks. This is a very “low threshold” approach to the Bible: it is not understood as a norm; no dogmatic determinations are made; and so there is no strong awareness of a canon.

The attempt to decanonize the Old Testament or place it at the same level as the Apocrypha always results in a crisis situation: “The Old Testament will be up for debate when the gospel becomes murky.” So it is a crisis phenomenon, that we have to depart from the (seemingly!) murky in order for the (supposedly!) essentials to become clearer. The subject of the “Old Testament” has contributed to this crisis, in that it is understood essentially as a historical subject, oriented towards the past rather than the future. In this context, reference was made later in the discussion to the approaches of Frank Crüsemann und Jürgen Ebach.

The speaker listed several components of Schleiermacher’s thought which related to the Old Testament: the New Testament was the faith document of the early Christians; there were references to the Old Testament in the New Testament, but these concerned only historical aspects, not grounds of faith; the Old Testament was the legacy of a less developed religion, possessed therefore less dignity, and was perceived as somewhat alien, while the New Testament was understood to be distinct from the Old; the brilliance of the gospel was dulled by the proximity of the Old Testament.

Von Harnack took a more positive stance towards the Old Testament, particularly the Prophets. He sees in the Old Testament, however, a religion steeped in legalism and ritualism which was only broken by Christ; with Christ, the Old Testament had become irrelevant.

Gerhard von Rad thought very differently from this. For him, the Torah was not a monolithic block; rather, it witnessed to a movement “forwards,” because tradition had to be reinterpreted again and again. So also, the Jesus-event required interpretation, and this through recourse to the Old Testament, namely the Pentateuch, the Prophets, and the Wisdom Literature; this was not “e-mancipation” (leaving the Old Testament) but “mancipation” (taking the Old Testament in hand). Schüle’s closing point was that the question of Jesus Christ must once again be a component of Old Testament research. The influence of the Old Testament on the New Testament scriptures must be researched. Therefore, we can learn from Jewish biblical research.

The retired Württemberg state rabbi Dr. Joel Berger gave a lively presentation exploring “How Jews Read and Understand the Bible: An Orthodox Perspective.” Jews, as he began by asserting, do not “read” the Torah; they “study” it. Moreover, the Torah is not only “text” but also “revelation.” As he put it, “If Slenczka wants to leave us alone with the Old Testament—okay!” Scripture study is not about knowledge, but about living devotion, about imitating the saints. To learn from Abraham means to learn action.

After the Orthodox rabbi, a representative of the liberal wing of Judaism spoke: Rabbi Dr. Edward van Voolen of the Abraham Geiger College in Potsdam. His theme was “Love of Teaching: Jewish Exegesis of the Tanakh.” According to the rabbi, the Torah establishes tradition; the Torah was given to Moses, who passed it on to Joshua, who passed it on to the Elders and so on from generation to generation. Based on section Baba Mezi’a 59b of the Babylonian Talmud, van Voolen explained that the text of the Torah must be interpreted anew again and again, which represents our adulthood and with it our fundamental rejection of any dogmatism or fundamentalism. The interpretation of the Word of God is given into human hands. According to the Talmud Chagigah 3b, texts always contain several possible interpretations—even different ones. Does this lead to anarchy in exegesis? Not when the doctrine is being constantly renegotiated. Dialogue is necessary here.

The section on “Texts and Community” was opened by Dr. Alexander Deeg, Practical Theologian from Leipzig, and his paper “Hermeneutical Problems and Homiletical Opportunities: Preaching Texts from the Old Testament.” At the outset he introduced the discussion process with the compilation of a new series of pericopes. In doing so, he noted that there was great interest in including more Old Testament texts. Old Testament texts were not now perceived as foreign, but as true-to-life and of direct concern to people. In connection to this, he referred to the Protestant practice of reading daily watchwords: the nucleus of the watchwords is comprised of an Old Testament verse, to which a New Testament verse is matched. Moreover, self-selected scriptures for baptism, confirmation, and wedding ceremonies are often taken from the Old Testament. There are also countless examples of art and culture with Old Testament echoes. For instance, he found 3750 instances of biblical traces in modern lyrics alone.

One ground for this was that the Old Testament includes a wide variety of genres, and contains texts originating from an extremely long span of time and out of diverse life experiences. Exodus stories, lamentations, and biblical laws are not abstract treatises, but texts with great earthiness.

Concerning the “professorial problematization” of this enthusiasm for the Old Testament, the speaker stated that Jews are the first ones to whom these texts are addressed, and so it is easy to run the risk of monopolizing or even expropriating them. Beyond that, the choice of texts is rather selective: people choose “nice” selections and avoid “nasty” ones (displays of violence, psalms that curse). For many Christians, the Psalms constitute a natural supplement to the New Testament—baptized as quasi-Christian.

In dialogue between Jews and Christians, there must be an unlearning of the traditional Christian methods of handling the Old Testament, which rest on categories like “promise and fulfilment,” “universalist” versus “particularist,” “antithetical,” as in “christological interpretations.”

A new hermeneutic must be followed:

- The Old Testament is a necessary background of Christ, without which we do not know what we are talking about.

- The Old Testament describes a history into which we listen, in which we belong, but which, at the same time, is the history of Israel and Judaism.

- The Old Testament is the “No” to Jesus as the Messiah, which we have to hear and which protects us from any triumphalism.

To the last point, the texts of Israel illustrate that where there is a spillover of the promise [from Judaism to Christianity], there is also a void in the fulfillment, which makes it clear that we are both waiting, expecting—both separately and together.

From the Jewish side, Rabbi Dr. Andreas Nachama, Director of the Topography of Terror in Berlin, addressed the theme: “The Reception of the Biblical Text in the Community: Preaching on Texts from the Tanach.” His basic thesis concerning the debate at hand was that Jews can actually be, in the first instance, indifferent to the ways in which Christians see the texts of the Old Testament. Studying the Torah and the other scriptures forms the basis for the cohesion of the Jewish community. Studying the Torah means, in the first instance, that the text is carefully recited, intensively read. To understand, we have “to read not only the black of the letters, but also the white between them.” If we read the Old Testament only as a historical text, it is rather uninteresting; if, however, we read the text in such a way as to be personally involved, then the Passover story from Exodus, for example, becomes immediately existential: it is as if we ourselves are being liberated from slavery and bondage.

Jewish stories attempt to make the text come alive approximately in the manner of the Midrash. In this stream of tradition, the year 70 after that time is particularly important: the loss of the temple demands a paradigm shift. Religion can no longer be based on temple worship, priestly service, and sacrifice, but must now “work anywhere.” Out of the traditional religion of sacrifice, two new developments have emerged: Rabbinic Judaism and Christianity.

After the French Revolution, a liberal stream arose alongside the orthodox life of faith. Nachama explained the liberal approach using the example of dealing with homosexuality: the texts must be maintained, but the interpretation will change due to the fundamental changes in the cultural context, and after that the corresponding conduct will change. It is important in Jewish-Christian dialogue that Jews and Christians compare notes on their respective ways of handling the texts of the Tanakh.

The conference section “Text and Controversy” was cancelled, since the anticipated discussion participant Professor Slenczka refused to take part. In a letter to the speakers, he mentioned that the program—unlike what was previously discussed—ultimately pursued the goal of a “statement” of his position in order to arrange an “ostracism,” without him having the opportunity to adequately defend himself against “misinterpretations” and “insinuations.” He accused the Protestant Academy of “fear of debate.”

As a result, the final day—Thursday, December 10, 2015—began under the heading “Text and Jewish-Christian Dialogue,” with a presentation by Dr. Rainer Kampling, Professor of Biblical Theology at the Free University of Berlin. It was entitled, “‘For the One God is the Creator of Both’: A Roman Catholic Perspective.” Based on the document “Decretum de librissacris” from the Council of Trent (1546), the speaker explained that, without the Old Testament, not only would Christians be rid of their God, but also they would run into a linguistic homelessness in their religious existence. At the time of the Reformation, neither Protestants nor Catholics ever considered whether the Old Testament was fully valid, but rather only considered which scriptures could be taken in a more or less binding way. Thus the representative of the old belief, Eck, argued that the Maccabean Books were indeed not in the canon, but had to be believed canonically, while Luther retorted that only the canon is canonical.

On the question of the validity of the Old Testament and New Testament, the council determined that “Unus deus sit auctor” (“God alone is the author”), where “auctor” means “originator” and not “writer.” To fix the canon, the council decreed once and for all that the specified scope of the canon itself become an object of faith, and not only the content of the canon. Thus the Old Testament is in a full sense the Word of God, meaning that, in the Roman Catholic Church, no theology can modify this principle. This issue could well revolve around ways of reading.

So then the formula of the Pontifical Biblical Commission’s “The Jewish People and their Sacred Scripture in the Christian Bible” (2001): “The Jewish reading of the Bible is a possible one, in continuity with the Jewish Sacred Scriptures [from the Second Temple period].”

The closing session of the conference was comprised of a discussion round under the question “Where does Jewish-Christian dialogue stand, and where is it going?” with the participants: Bishop Markus Dröge, Professor Julius H. Schoeps, Professor Christoph Markschies, Rabbi Joel Berger, Professor Rainer Kampling und Professor Micha Brumlik, moderated by Dr. Werner Treß und Dr. Eva Harasta.

Brumlink began from the concept of “shyness with strangers” (“Fremdelns”), which—in the development of a child—is always noticeable when fears arise due to changes in the environment and the child has to form new relationships. The stranger can appear as a source of fascination or trembling.

Bishop Dröge showed—starting with the image of a pulpit with Moses as a fundamental pillar—that Judaism has a continuing importance as a sign of God’s faithfulness. Moreover, the Church must repeatedly “make clear the fundamental role of the Jewish faith for the Christian faith.”

Schoeps referred to the “Rhenish Synodal Resolution” of 1980. At that time, he was full of hope for the dawn of better times; but then the resolution was repeatedly criticized by various parties (and immediately by the Bonn and Münster theological faculties), who fundamentally rejected the resolution. For Schoeps, this aroused a skepticism over the sense of Jewish-Christian dialogue.

State Rabbi Berger was intensely critical of the behavior of specific parts of the Protestant Church (“Pietcong” [i.e. radical Pietists] in Württemberg parlance), asserting that dialogue would be used as a cover for pure Jewish mission, and that with highly questionable methods. Along the way, he called attention to the destructive activity of the so-called “Messianic Jews.”

The church historian Christoph Markschies pointed to the guilty history of theology at German universities. At the “Institutum Judaicum” [a preparatory course for Protestant theologians intending to engage in missionary work among Jews], the Old Testament was taught as a “placeholder of pre-Christian experience of God.” He expressed the wish that an information sign would be placed beside the memorial plaque for Dietrich Bonhoeffer in Berlin’s Humboldt University, which would indicate that in 1936 this university dismissed Dietrich Bonhoeffer as private docent, and moreover that the church historian Erich Seeberg energetically campaigned for the abrogation of the Old Testament and its replacement with texts from Meister Eckhart.

Professor Kampling stressed that since the [Second Vatican] Council resolution “Nostre aetate”—promulgated exactly 50 years ago and just now this day again realized through a Vatican pronouncement—it has become increasingly clear that Judaism is in salvation; Jesus as the mediator of salvation remains a mystery. “There is a thin trace of friendliness towards Jews in the history of theology!”

Overall, it was agreed that Jewish-Christian dialogue has generated many positive things. Bishop Dröge brought forth as evidence “Study in Israel” [a year-long study program for German theology students at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem], new exegesis (“Preaching Meditations in Christian-Jewish Context” [a publication from “Study in Israel”]), various meetings and significant changes in preaching and religious education. Brumlik even spoke of a “success story.”

More critically, Professor Markschies noted that the departure taken in 1980 had not been carried on decisively enough, especially in the direction of the theological education of the following generations. Many emerging theologians simply lack a solid study of the Old Testament. Correspondingly, Micha Brumlik asserted that it is necessary for more Jewish people, especially from the younger generation, to become interested in Jewish-Christian dialogue. The Reformation jubilee of 2017 would surely illustrate this—there are still aspects [of the Jewish-Christian relationship] to be negotiated that revolve around more than simply narrowly religious matters.

Finally, it must be noted that despite the refusal of Slenczka to attend the meeting, a productive exchange of views took place, in which both Jews and Christians highlighted the importance of the Old Testament. The presentations illustrated how much the question of the importance of the Old Testament relates to the very core of Christian theology. It became clear that not the detachment but the engagement with the diversity and the richness of the canon is not only theologically necessary but also illustrative of the great benefit derived for Christianity from the participation in the Hebrew Bible. Thus the title image for the conference—the sculpture “Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time” by Joshua Koffman—was very well chosen. The artwork illustrates how Jews and Christians can enter into a dialogue on eye level with one another on the foundation of a common collection of texts, and how the will of God can be rightly understood in their sacred scriptures.

Despite its theologically-sounding title, this latest work by Ian Kershaw, who is one of Britain’s most distinguished contemporary historians, is a masterly synoptic history of Europe, designed for the general reader. In this work, Kershaw expands on his previous interest in Nazi Germany to cover what he calls Europe’s “era of self-destruction,” which places Nazi Germany in its wider context of a continent-wide series of disasters in the first half of the twentieth century. Nevertheless he also includes a short but valuable section on “Christian Churches, Challenge and Continuity”, placing emphasis on the political and social developments affecting the Christian churches within the wider European setting.

Despite its theologically-sounding title, this latest work by Ian Kershaw, who is one of Britain’s most distinguished contemporary historians, is a masterly synoptic history of Europe, designed for the general reader. In this work, Kershaw expands on his previous interest in Nazi Germany to cover what he calls Europe’s “era of self-destruction,” which places Nazi Germany in its wider context of a continent-wide series of disasters in the first half of the twentieth century. Nevertheless he also includes a short but valuable section on “Christian Churches, Challenge and Continuity”, placing emphasis on the political and social developments affecting the Christian churches within the wider European setting.

In post-WWI Germany, law had been a most respected entity, with the country thriving thanks to its most capable lawyers and judges, many of them Jewish. In 1933, no law could inhibit the Third Reich’s political and military rise to power. In a step-by-step process, the National Socialist government dismantled constitutional law, usurped justice and created a lethal totalitarian system that soon engulfed Germany and all of Europe. Redefining the nation as a pure political and biological organism, the Nazi government imposed legislation that reinforced its ideological program in all aspects of German life, with a focus on race, business, religion and medicine. Filmed at Boston College during a conference on Nazi law, as well as in Nuremberg, Munich and Dachau, this documentary relies on the expertise of scholars from Germany, France, Israel and the US. They come from the areas of medicine, law, Jewish Studies, theology and other disciplines.

In post-WWI Germany, law had been a most respected entity, with the country thriving thanks to its most capable lawyers and judges, many of them Jewish. In 1933, no law could inhibit the Third Reich’s political and military rise to power. In a step-by-step process, the National Socialist government dismantled constitutional law, usurped justice and created a lethal totalitarian system that soon engulfed Germany and all of Europe. Redefining the nation as a pure political and biological organism, the Nazi government imposed legislation that reinforced its ideological program in all aspects of German life, with a focus on race, business, religion and medicine. Filmed at Boston College during a conference on Nazi law, as well as in Nuremberg, Munich and Dachau, this documentary relies on the expertise of scholars from Germany, France, Israel and the US. They come from the areas of medicine, law, Jewish Studies, theology and other disciplines.

Pavlush focuses primarily on four events: the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann and the wave of antisemitism that swept Germany around the same time; the controversy about Rolf Hochhuth’s 1963 play Der Stellvertreter (The Deputy); the 1967 Six-Day War; and the 1979 national broadcast in the FRG of the U.S. television docudrama The Holocaust. In a separate chapter she examines the 1968, 1978, and 1988 anniversaries of the November 9 pogroms (“Kristallnacht”) as indicators of how East and West Germans viewed their history.

Pavlush focuses primarily on four events: the 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann and the wave of antisemitism that swept Germany around the same time; the controversy about Rolf Hochhuth’s 1963 play Der Stellvertreter (The Deputy); the 1967 Six-Day War; and the 1979 national broadcast in the FRG of the U.S. television docudrama The Holocaust. In a separate chapter she examines the 1968, 1978, and 1988 anniversaries of the November 9 pogroms (“Kristallnacht”) as indicators of how East and West Germans viewed their history. Despite the excellent contributions of such authors as James Zabel, Doris Bergen and Robert Ericksen, Solberg feels that “far too few people in or out of the academy know far too little“ about the conduct of the churches In Hitler’s Germany. But her extended introduction clearly indicates her approach to answering the questions posed by her documents: specifically what role did this German Christian Faith Movement play in the wider picture; how successful or significant were its supporters in the rise and maintenance of Nazism, at least up to 1940; and how should Christians and churches today learn from this example of a church undone? Her skillful translations of the writings of several prominent members of this movement will be of considerable value to those who do not read German, but it would have been helpful to have a biographical note or appendix outlining the careers of these authors. Her conclusion is that this was not a unique episode, that the conflation of political, racist and nationalist ideas with theological witness is a constant temptation, and therefore that the German experience in the 1930s deserves further study by both theologians and historians.

Despite the excellent contributions of such authors as James Zabel, Doris Bergen and Robert Ericksen, Solberg feels that “far too few people in or out of the academy know far too little“ about the conduct of the churches In Hitler’s Germany. But her extended introduction clearly indicates her approach to answering the questions posed by her documents: specifically what role did this German Christian Faith Movement play in the wider picture; how successful or significant were its supporters in the rise and maintenance of Nazism, at least up to 1940; and how should Christians and churches today learn from this example of a church undone? Her skillful translations of the writings of several prominent members of this movement will be of considerable value to those who do not read German, but it would have been helpful to have a biographical note or appendix outlining the careers of these authors. Her conclusion is that this was not a unique episode, that the conflation of political, racist and nationalist ideas with theological witness is a constant temptation, and therefore that the German experience in the 1930s deserves further study by both theologians and historians. This account pays little attention to theology, but instead follows in the footsteps of such authors as Grace Davie and Callum Brown in emphasizing the sociological patterns he discerns in the Church of England’s development during the fifty years following the Second World War. Itzen lays particular stress on the views and the impact of the major church leaders on the political and social life of the nation, and makes extensive use of the archives held in Lambeth Palace, the residence of successive Archbishops of Canterbury. He also appends short but useful biographical details of many church leaders. The result is a well-informed but not uncritical account of the sometimes controversial stances adopted by the church, and the often critical responses by politicians, for instance during the Suez Crisis in the 1950s, or during Margaret Thatcher’s term as Prime Minister in the 1980s.

This account pays little attention to theology, but instead follows in the footsteps of such authors as Grace Davie and Callum Brown in emphasizing the sociological patterns he discerns in the Church of England’s development during the fifty years following the Second World War. Itzen lays particular stress on the views and the impact of the major church leaders on the political and social life of the nation, and makes extensive use of the archives held in Lambeth Palace, the residence of successive Archbishops of Canterbury. He also appends short but useful biographical details of many church leaders. The result is a well-informed but not uncritical account of the sometimes controversial stances adopted by the church, and the often critical responses by politicians, for instance during the Suez Crisis in the 1950s, or during Margaret Thatcher’s term as Prime Minister in the 1980s. To be sure the tasks of European reconstruction and reconciliation were formidable for politicians and churchmen alike. Priority had to be given to the immense task of caring for the vast millions of bombed-out, brutalized, and displaced populations. Most churches were still tied to their own national affairs and regarded plans for European integration as lying outside their spiritual domain. However a few of the survivors of the pre-war ecumenical bodies, led by the valiant and dynamic personality of the Dutch Calvinist, Visser ‘t Hooft, General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, recognized the importance of seeking closer relations with those politicians involved in European reconstruction. The World Council, which achieved its long-delayed inauguration in 1948, almost immediately suffered a grievous, if not unexpected, blow by the rejection of its invitation to the Vatican to have Roman Catholics as full members. The initiative in European affairs was therefore left to the Anglicans, the Protestant leaders of northern Europe, and a handful of Orthodox churchmen in Eastern Europe. So too, those politicians who had expected that the legacy of unbridled nationalism under Hitler would lead to a willingness to cooperate more closely in pan-European revival were soon to be disappointed by the brusque refusal of the Soviet government to entertain any such measures for the areas of Eastern Europe under its military control. In both the political and religious fields, therefore, expectations had to be cut down, and prognoses for European integration modified, often drastically.

To be sure the tasks of European reconstruction and reconciliation were formidable for politicians and churchmen alike. Priority had to be given to the immense task of caring for the vast millions of bombed-out, brutalized, and displaced populations. Most churches were still tied to their own national affairs and regarded plans for European integration as lying outside their spiritual domain. However a few of the survivors of the pre-war ecumenical bodies, led by the valiant and dynamic personality of the Dutch Calvinist, Visser ‘t Hooft, General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, recognized the importance of seeking closer relations with those politicians involved in European reconstruction. The World Council, which achieved its long-delayed inauguration in 1948, almost immediately suffered a grievous, if not unexpected, blow by the rejection of its invitation to the Vatican to have Roman Catholics as full members. The initiative in European affairs was therefore left to the Anglicans, the Protestant leaders of northern Europe, and a handful of Orthodox churchmen in Eastern Europe. So too, those politicians who had expected that the legacy of unbridled nationalism under Hitler would lead to a willingness to cooperate more closely in pan-European revival were soon to be disappointed by the brusque refusal of the Soviet government to entertain any such measures for the areas of Eastern Europe under its military control. In both the political and religious fields, therefore, expectations had to be cut down, and prognoses for European integration modified, often drastically. The extent and importance of religious faith in the First World War is undoubtedly one of the great rediscoveries of the centenary years. Among the belligerent empires and nations, religion proved to be a vital sustaining and motivating force, with the Ottoman war effort cloaked as a jihad, the United States entering the war on Good Friday 1917, and even professedly secular societies such as France experiencing a degree of religious revival. At the same time religious convictions also provided some of the most powerful critiques of the war, contributing to tireless peace-making efforts by Pope Benedict XV and to the stand of thousands of conscientious objectors in Great Britain and the United States. Faith also inspired many of the women who were active in war resistance and initiatives for peace, including Quakers, feminists and Christian socialists who were involved in the Hague Peace Congress of 1915, the resulting Women’s International League, and also grassroots action such as the Women’s Peace Crusade, which was launched in Glasgow in the summer of 1916.

The extent and importance of religious faith in the First World War is undoubtedly one of the great rediscoveries of the centenary years. Among the belligerent empires and nations, religion proved to be a vital sustaining and motivating force, with the Ottoman war effort cloaked as a jihad, the United States entering the war on Good Friday 1917, and even professedly secular societies such as France experiencing a degree of religious revival. At the same time religious convictions also provided some of the most powerful critiques of the war, contributing to tireless peace-making efforts by Pope Benedict XV and to the stand of thousands of conscientious objectors in Great Britain and the United States. Faith also inspired many of the women who were active in war resistance and initiatives for peace, including Quakers, feminists and Christian socialists who were involved in the Hague Peace Congress of 1915, the resulting Women’s International League, and also grassroots action such as the Women’s Peace Crusade, which was launched in Glasgow in the summer of 1916.