Association of Contemporary Church Historians

(Arbeitsgemeinschaft kirchlicher Zeitgeschichtler)

John S. Conway, Editor. University of British Columbia

May 2009 — Vol. XV, no. 5

Dear Friends,

Contents:

1) Obituary: Albrecht Schoenherr

2) Book reviews:

a) Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Vol. 10

b) Söderblom, Letters

c) Spicer, Hitler’s Priests

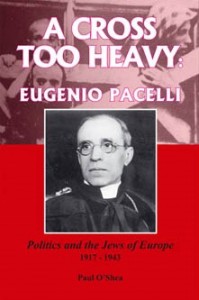

d) Shea, A Cross Too Heavy

1) It is with regret that we learn of the death at the age of 97 of Albrecht Schoenherr, the retired Protestant bishop of Berlin-Brandenburg in Potsdam on March 9th.He was the last surviving student of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s illegal seminary at Finkenwalde, near Stettin in 1936-7, and subsequently was the leading figure in the postwar life of the church in what was then East Germany.

The present Bishop, Wolfgang Huber, described Schoenherr as an impressive witness to Jesus Christ whose steadfastness had enabled his church community in East Germany to resist the attacks of the Communist state authorities, and defended the integrity of the gospel from encroachments from political interests. He was born in 1911, and as a student attended both Tuebingen and Berlin universities where he met Dietrich Bonhoeffer as a young lecturer. After the Nazi seizure of power, and the outbreak of the Church Struggle, Schoenherr was influenced by Bonhoeffer to join the Confessing Church, the minority group which strongly opposed all attempts to introduce Nazi ideas into the church. He then joined the first course given under Bonhoeffer’s direction at the seminary at Finkenwalde, near Stettin in 1935, and subsequently stayed for a second year as Bonhoeffer’s assistant. In later years he referred to this experience as the most valuable in his career.

Like most of his contemporaries, Schoenherr was conscripted for the army during the war, and served in Belgium and Italy. He was there taken captive, and then became chaplain to two German POW camps until his release in 1946. On returning to East Germany he established a similar seminary for Brandenburg and led this for seventeen years. In 1963 he became General Superintendent for Berlin-Brandenburg, during the period of severe repression by the Communist government of what had become the German Democratic Republic. One of the most serious contentions arose over the continuing links between the Evangelical Church there and its partners in West Germany. Otto Dibelius, for example, who was Bishop of Berlin and Brandenburg, but resided in West Berlin, was forbidden to exercise his functions in East Germany, and militantly attacked the Communist regime in the eastern part of his diocese. Schoenherr had then the unenviable task of trying to cope with the political and pastoral problems which ensued. He recognised that the political divisions of the country were too strong for the church to overcome, and hence sought to persuade his following in East Germany to declare their independence from their western partners for the sake of their better witness to the new political reality. This came to be called “The Church in Socialism” but remained a controversial step, since it appeared to welcome the idea of collaboration with the Communist regime. In fact Schoenherr’s steadfastness was a staunch defence against any such capitulation. In 1969 he was elected founding president of the Federation of Protestant Churches in the German Democratic Republic, and in 1972 was elected to be Bishop of (East) Berlin and Brandenburg after the diocese was split. He vigorously defended his churches’ interests, and in so doing earned the respect of the political regime. In 1978, he negotiated an agreement with the then leader of the East German government, Erich Honecker, which brought the church major alleviations, and official recognition of its situation. This included permission to make religious broadcasts on radio and television, pastoral visits to prisons, and other advantages. These undoubtedly prepared the way for the church in East Germany to play such an active role in the turbulent events of 1989.

But Schoenherr retired from these church responsibilities in 1981, though he continued for twenty years to travel widely lecturing on Bonhoeffer’s legacy and teaching courses for the laity called Conversations on Faith. He was naturally active in the International Bonhoeffer Society and was a co-editor for the comprehensive German edition of Bonhoeffer’s collected works. He himself wrote his autobiography in German “But the time was not lost”.

He married twice, had six children, 20 grandchildren and 29 great-grandchildren. He will be remembered as a stalwart upholder of Protestant church orthodoxy during times of great political tensions, and a leader who set a standard of uncompromising faithfulness to the gospel of Christ.

2a) ed. C. Green (English edition), Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Barcelona, Berlin, New York 1928-1931. (Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works, Volume 10) Minneapolis: Fortress Press. 2008. 764 pp. ISBN -13-978-0-8006-8330-6.

The English translation of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s collected works proceeds apace. The latest to appear is volume 10, which introduces us to the young Bonhoeffer, covering the period from his twenty-second birthday until he is twenty-five, i.e. from 1928 to 1931. During these years he spent two extensive periods abroad, first in Barcelona, as assistant to the Chaplain of the German Protestant community, and second, as a post-doctoral student at Union Theological Seminary in New York. In 1928, Bonhoeffer had just completed his PhD thesis for the theological faculty of the University of Berlin, and was faced with the decision whether to seek his vocation as a pastor in the German Evangelical Church, or to turn to an academic career in theology. It was in part to test this choice that he accepted the posting to Barcelona. He was in any case too young to be ordained, and a certain prompting to see beyond Germany’s borders led him to accept. His subsequent visit to the United States was far more purposeful. It arose from his agreement with his mentors’ view that any future German theologian should be aware of the theological currents in the New World.

During both of these absences from home, Bonhoeffer maintained a lively correspondence with his family and friends, almost all of which has been astonishingly preserved. Together with various surviving papers containing the texts of addresses and sermons he delivered, along with lecture notes taken in New York, this volume brings together a remarkable corpus of over 600 pages. This material has all been carefully edited by Bonhoeffer’s friend Eberhard Bethge, and is now most skilfully translated into a fluent and comprehensible English. Clifford Green adds a valuable introduction to the English edition. The volume serves to show us an interesting stage in the development of this talented, even precocious young man.

Life in the German expatriate community in Barcelona, consisting of businessmen and merchants, offered little or no stimulus to Bonhoeffer’s theological development. He commented wickedly on his Pastor’s never reading any theological book, and on the disastrous tone of his sermons. By contrast Bonhoeffer preached lengthy and dense sermons, mainly reflecting the teachings of Karl Barth. He did however make himself popular through his work with the community’s children. His lack of Spanish, of course, was a barrier to assessing conditions in Spain. But his letters contain no explicit comments on the political or social conditions he found there. It was not until he returned to Berlin a year later that he could resume work on his post-doctoral thesis, needed to qualify for an academic position in his own department of systematic theology.

His sojourn in America eighteen months later was far more productive, both personally and theologically. At first he was shocked to find how undogmatic and indeed superficial was the kind of preaching offered in most of the main-stream churches in New York. An optimistic immanentism, coupled with a pragmatic desire to build up their congregations, seemed to be the main preoccupation of the Protestant clergy. He was equally shocked by the absence of dogmatic teaching at Union Seminary. It was only when he was introduced by a fellow student of Afro-American descent to the black churches in Harlem, especially the Abyssinian Baptist Church, that his enthusiasm was aroused. Here, he said, “one could really still hear someone talk in a Christian sense about sin and grace and the love of God. The black Christ is preached with captivating passion and vividness”. This experience of the religious fervour among an oppressed people deeply affected his personal beliefs. So too he learnt much from the insights of his fellow student, the Frenchman Jean Lasserre, who confronted him with the claims of Jesus, especially those recorded in the Sermon on the Mount, which was to become so central in Bonhoeffer’s own thinking. It was the beginning of an inspiring but costly discipleship.

Bonhoeffer’s disdain for the weaknesses of American religiosity, and his condescension about the teaching of theology at Union, can be attributed to the widespread feelings of superiority held by the European elite about American life and customs. Bonhoeffer himself came from an elite academic family, he had studied at Germany’s foremost university, under Adolf von Harnack, generally acknowledged as Europe’s most notable scholar.

His theological cogitations, especially on the philosophy of religion, were highly esoteric, abstract and demanding of great intellectual comprehension. He was unlikely to find any counterpart on the other side of the Atlantic. Some of his fellow students were undoubtedly put off by his aloofness, his conservatism and his German origin. But that is what he was. His class-based political sympathies can be seen in the notes he left for an address on the subject of “Germany” given to a mass rally of schoolchildren shortly after his arrival. In this talk he rehearsed the well-worn litany of complaints by German conservatives, beginning with Germany’s disastrous loss of the war, the cruel imposition of a hunger blockade by the Allies, the scandal of the Versailles Treaty, the loss of German territory and colonies, the harshness of the burden of reparations, the economic hardships of the inflation and then of the depression, and above all the humiliation of the so-called War Guilt Clause, blaming Germany for the origins of the war. He made no mention of the sweeping German aggressions, or of the innumerable victims and sufferings these actions had caused, especially in France and Belgium. It is probable that at the time Bonhoeffer was not aware how far these views were being exploited by the Nazis.

It was only after he returned from America that he was forced to see how readily his fellow middle-class Germans were letting themselves be seduced. But his own national sympathies remained. When, eight years later in 1939 he returned to New York, and was offered a chance to escape from Nazi tyranny, he famously replied: “I shall have no right to take part in the restoration of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the tribulations of this time with my people”. Exile or emigration was not a real option. He remained rooted in his German and Christian heritage.

This volume ends when Bonhoeffer returned to Berlin in mid-1931. He was immediately caught up in new and challenging engagements in the ecumenical movement, in social work projects in the Berlin slums, and in his teaching responsibilities at the Berlin University. All made him aware of the growing crisis in Germany, which was to culminate with Adolf Hitler’s rise to power on January 30th, 1933. While it is tempting to believe that Bonhoeffer’s stay in America influenced his political stance thereafter, this would not seem to be borne out by the evidence. But this volume depicts a highly thoughtful young professional enlarging his horizons in a number of different directions, such as his newly found interest in pacifism, which later on were to have a significant impact on his subsequent career.

JSC

2b) Dietz Lange (ed.) Nathan Söderblom: Brev – Lettres – Briefe – Letters. A selection from his correspondence, 528 pp. incl. frontispiece, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006, ISBN 13:978-3-525-60005-4; ISBN 10:3-525-60005-4

This stout volume certainly does something to maintain the presence of its illustrious subject in the modern academic catalogues. Söderblom, the prophetic guiding spirit of early twentieth-century ecumenism and the guiding spirit behind the 1925 Stockholm conference, was deeply admired in Britain and the United States. At least one official photograph of Bishop Bell of Chichester places him purposefully beside a portrait of his Swedish hero. If this long shadow has since receded, it reflects a good deal upon a decline in our interest in themes which once excited both the idealist and the scholar. It is surely time that we retrieved them.

Dietz Lange, a German scholar, here edits a great variety of materials with authority. This is a valuable compendium, designed to reveal the richness of Söderblom’s fascinations and the diversity of his friends and allies. It is, as its title pronounces, an international collection for which the committed reader will need English and German. The admirable introduction is in English; the Swedish letters are duly presented in the original and translated into English.

Lange finds his Söderblom at large in three guises: the pastor, the professor and the archbishop. In all respects, an editor has his work cut out for him: Söderblom, Lange remarks patiently, was ‘a tireless letter writer’, who would busily dictate letters even as he walked along the street (p. 9). The shelves of Uppsala University Library now stagger under the weight of no less than 38,000 letters, dairies and notes. And yet what accumulates here is not merely official and dry, but lively and rich. For Söderblom enjoyed people and he inhabited many distinct dimensions with apparent ease. Church historians might note his conviction – in contradiction to Harnack – that the history of religion belonged not solely in the history department, but in the theological faculty.

The great bulk of this collection lies, very naturally and properly, with the Söderblom’s years as archbishop of Uppsala. Although his appointment came as a shock to the politicos of his church, it was a public role for which he was brilliantly qualified. A convinced internationalist, his public work now coincided with the outbreak of the First World War and, subsequently, a new, bustling age of conferences and movements. It was in this landscape that those from the English-speaking world encountered him. In this collection, it is no surprise to find him in eager dialogue with the assorted giants of German Protestantism: Otto Dibelius, Adolf von Harnack, Rudolf Otto and Frierich Heiler (quite a collection in itself). But here, too, are the Scandinavians, Gustaf Aulén, Eivind Berggrav and Birger Forell, the American, Henry Atkinson, the Scot David Cairns and Archbishop Davidson.

Altogether, this is a valuable volume which deserves the international readership for which it is so clearly designed. Both the tenacious editor and his committed publishers have every right to our gratitude.

Andrew Chandler, George Bell Institute at the University of Chichester

2c) Kevin P. Spicer, Hitler’s Priests. Catholic Clergy and National Socialism. De Kalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2008. 369 Pp. ISBN978-0-87580-380-5 (published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

(This review appeared first in the Catholic Historical Review, April 2009)

In 1933 the majority of Germans enthusiastically welcomed Hitler’s takeover of power. Amongst the Catholic population, there was a small number of priests who had already demonstrated their support of the man whom they believed would lead Germany into a new era of national greatness. Kevin Spicer has now provided us with a commendable account of the ideas and careers of 138 such men, who he designates as “brown priests”. His diligent and perceptive research in both the ecclesiastical and government archives in Germany examines these men’s motives, describes their advocacy of Nazi ideas and assesses the influence of their political activism.

Needless to say, Spicer, with all the advantages of hindsight, is highly critical of these priests, but also makes clear that, for the most part, so were their bishops at the time. Many were disciplined by their ecclesiastical superiors, not so much for their political zealotry, but for their failure to obtain the appropriate approval. Spicer gives numerous examples to show how these priests refused to give up their pro-Nazi political agitation, even when ordered to do so. And he draws attention to the difficulties such well-publicized activities caused to their bishops.

Most of these brown priests were convinced that their advocacy for the Nazi Party was fully compatible with their personal Catholic faith. And they had little difficulty in backing the Nazis’ antisemitism and racism, making use of the church’s traditional hostility towards Judaism, and their own prejudices against the alleged malevolence of German Jewry.

It is notable that over a third of these priests had doctorates in philosophy or theology, which they used to advance their mixture of German Catholicism and National Socialism. The more prominent of these promoters of the Nazi cause, such as the former Abbot Alban Schachleiter, have already appeared in earlier histories of the German Church Struggle. But Spicer gives us the fullest account in English of these individuals’ waywardness. Schachleiter, for instance, made much of his personal acquaintance with Hitler, championed an extreme German nationalism which had led to his expulsion from his abbey in Prague in 1918, was frequently the main speaker at Nazi rallies, and used his contacts to evade the restrictions placed on him by his superiors. When he died in June 1937, Hitler ordered that he should be given a state funeral, and sent his deputy, Hess, to attend.

Equally notorious were those brown priests who believed that their Nazi sympathies had thwarted their careers in the church and denied them their due recognition. Some even left the church and became ideological crusaders against their former colleagues. Albert Hartl, for example, whom Spicer scarcely mentions, held a high position in Himmler’s security intelligence service, and in 1941 was busy preparing plans for eradicating church influence in Germany once victory was achieved. (More information on Hartl’s nefarious activities can be found in the authoritative German companion volume by Wofgang Dierker, Himmlers Glaubenskrieger,Paderborn 2003).

Spicer also provides information about lesser-known figures,. many of whom were sent to obscure rural parishes, where they eagerly enough supported the Nazi Party in their pastoral ministry and parish activities for many years. Particularly difficult to assess is the extent to which these men’s fervent attachment to Nazi ideas was affected by the Nazis’ own anti-Catholic extremism. Spicer is not inclined to give them the benefit of the doubt and thus perhaps exaggerates their single-minded determination to conflate Nazism and Catholicism. At any rate, as he shows, in the aftermath, many brown priests were exculpated by denazification courts, and almost all eventually made their way back into public ministry.

Writing for an English-speaking audience about events on another continent which took place seventy or more years ago presents real difficulties, all the more since Spicer clearly has no sympathy at all for his subjects. But his purpose is clear: to draw attention to the folly and danger of allowing political fervour to distort the orthodox heritage of the church, or to sanction the fanaticism which only encouraged the Nazis in their radical campaigns, especially against the Jews. Such a theological mindset, he claims, closely paralleled the designs and actions of the Holocaust’s perpetrators. He also criticizes the bishops for focusing solely on the survival of the church and its sacramental mission, and for their failure to take a stronger stand against the antisemitic tirades of these brown priests. Even though their number was small, and by no means representative, and even though their influence clearly remained marginal, Spicer’s well-argued warnings against this trahison des clercs are indeed apposite in this sad chapter of German Catholicism’s history.

JSC

2d) Paul O’Shea, A Cross too heavy. Eugenio Pacelli. Politics and the Jews of Europe, 1917-1943. (Kenthurst, NSW, Australia: Rosenberg Publishing. 2008 Pp 392 ISBN 978-1877-058714).

Dietmar Paeschel, Vatikan und Shoa (Friedenauer Schriftenreihe. Reihe A: Theologie, Band 9) (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. 2007 Pp 150. ISBN 978-3-631-56828-6).

(This review appeared first in the Catholic Historical Review, April 2009)

The flood of books about Pope Pius XII continues unabated. But since no new documentation has appeared in the last ten years, and a major indispensable source, the papers of the Vatican Secretariat of State, are still secreted in the Vatican archive and are not yet released for public scrutiny, it is clear that many of these new books are not the result of new historical analysis or research. Instead, the character and policies of Pius XII are used as part of an on-going controversy about the authority and governance of the Roman Catholic Church. The participants seek to prove either the urgent need for reform of an outdated authoritarian institution, or regard Pius as an example of prudent leadership at a time of great political and military danger. With regard to his stance towards the Nazis` persecution and mass murder of the Jews, many vocal critics have turned Pius into a scapegoat. A less silent pope, with more active engagement, they believe, could and should have prevented, or at least mitigated the Nazi Holocaust. But is there historical evidence to substantiate such far-reaching claims, or is this purely the product of wishful thinking? On the other hand, are those seeking to defend Pius doing so in order to exonerate the institution at whatever cost to historical candor?. Both books under review attempt to answer these questions.

Paul O`Shea is a young Australian scholar who rejects as superficial those widespread accusations which have depicted Pius as Hitler`s Pope, too lenient towards the Germans, an antisemitic bigot, insensitive to the fate of Hitler`s victims, or motivated only by a calculating political opportunism. Instead, O`Shea concentrates on seeing Pacelli as the inheritor of a long theological tradition, enshrined in the Vatican`s centuries-old stance, whereby the Jews were seen as a renegade people, deserving of conversion but remaining a witness to God`s eternal mercy. O`Shea`s main contention is that centuries of Christian Judeophobia and antisemitism culminated in the papal silence during the Holocaust. On the other hand, O`Shea notes, Pius cannot be dismissed as a bystander. He agonized over every word he uttered on the fate of the Jews, and his discreet actions on behalf of individuals saved many lives. But the widely-held perception that the Papal moral influence would be resolutely and loudly deployed was disappointed. And the burden of O`Shea`s critique is that he shares this disappointment. He is therefore critical of Pius for not protesting more forcefully, since `there is a moral duty to speak out in the face of evil, regardless of the consequence` (p. 28).

O`Shea is hardly the first to advance such an opinion, but he fails to point out one all-important factor. For any far-reaching, let alone successful, measures to assist the Jews in war-torn Europe, the Catholic magisterium would have had to undertake a major reversal of its theological position, to abandon its historic anti-Judaic stance, and to embrace the theology first adumbrated in 1965. But no such alteration took place. Nor is there any evidence that Pius XII would have supported such a major theological revision. This process only began after his death. O`Shea`s contribution is to show how the Vatican`s mind-set, its entrenched conservatism, and Pacelli`s own theological training, all combined to reinforce a consistent, if now regrettable, attitude of regarding Jews as second-class citizens or the victims of history. The result was a theological rather than a moral failure.

Dietmar Päschel`s short account of the relations between the Catholic Church and the Jewish people during the course of the twentieth century, is clearly designed for German students. It includes a useful German translation of some of the important documents, as well as a German bibliography. Dominated by the horrifying events of the Shoah, his narrative divides into two separate halves. The first seeks to explain the failure of the Vatican and the German Catholic hierarchy to prevent, or at least alleviate, the Nazis` ferocity against the Jews, while the second outlines the steps taken to draw up a new and more sympathetic stance by the Catholic authorities, beginning with the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s.

In Päschel`s view, the Nazis` radical hostility to both Jews and Catholics put the latter on the defensive. The Vatican`s attempt to obtain safeguards through the 1933 Concordat was largely a failure, and led German Catholics to concentrate on defending their own autonomy. Because of the deeply-rooted antisemitism in Catholic ranks, there was little sympathy for their fellow victims, the Jews. This reluctance was a contributing factor for the Vatican`s equal lack of strong protest against the Nazi atrocities. Those Catholic voices raised on behalf of the Jews, such as Edith Stein or Provost Lichtenberg, were too few to be effective. The Holy See maintained its silence, regarding the persecution of the Jews as a secular matter beyond its mandate. The readiness of the German Catholic hierarchy to support Hitler`s nationalist goals showed their capacity for complicit compromise. Despite the Vatican`s attempt to mobilize opposition to the errors of Nazi ideology, through its 1937 Encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, the result was poor. And the events of 1938 culminating in the November pogrom, demonstrated not only the Nazis` political mastery, but the failure of Catholics to take a stand, either through the Vatican or locally. Like O`Shea, Päschel deplores Pius` failure to protest, and is equally critical of the German Catholics` cowardice. Neither, he says, earned a halo.

In the second half of the book, the tone is warmer. Päschel presents the various stages of the far-reaching, if belated, change in Catholic attitudes, brought about by the impact of the Shoah,and also by the encouragement of Pope John XXIII. He gives an excellent summary of the debates in the Vatican Council, from which there finally emerged in October 1965, the significant document Nostra Aetate. The revolutionary achievement of this text, he rightly observes, was to remove any Catholic foundation for anti-Judaism. The ancient slander that Jews were responsible for Christ`s crucifixion was repudiated. Jews remain chosen by God. It was, Päschel argues, a unique and unprecedented paradigm change in Catholic theology.

This initiative in Catholic-Jewish relations was taken further by the decisive leadership of Pope John Paul II. During his long reign, he made dramatic visits to Israel, Auschwitz and the Roman synagogue. On each occasion he stressed the change in Catholic attitudes. But a 1998 document entitled We remember. A reflection on the Shoah seems to Päschel to be more of a Vatican bureaucratic defence than an acknowledgement of Catholic guilt. He justly criticizes the tendency to distort the lamentable record of Catholic prejudice for apologetic reasons. Much, he believes, still remains to be done. The historic guilt of the institution, rather than of individual Catholics, still remains to be acknowledged. Yet the reversal of the age-long anti-Judaic doctrines must be regarded as epochal, and hopefully irreversible. New theological impulses by the Vatican are, in Päschel`s opinion, indispensable to maintain the momentum, for improved Catholic-Jewish relations.

JSC

May I remind you once again that I am very glad to have any comments you may like to share. Please send them to my own address, as below, and do NOT press the Reply button, unless you wish to reach all the 500 subscribers to the Newsletter.

With every best wish,

John Conway

Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background.

Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background.

The editors, Maria Anna Zumholz and Michael Hirschfeld, discuss significant forthcoming works on both von Faulhaber and Jaeger to account partly for the brevity of the studies here (13). And while there is a detailed chapter by Raphael Hülsbömer on Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli – later Pope Pius XII – and his relations with the German bishops, there is no attempt to integrate the episcopate into Vatican politics or consider the complicated, at times strained relationship between the wartime pope and the bishops as a collective. The editors justify this in part by referencing the closed archives covering the wartime pontificate of Pius XII; they could not have known that the year following this volume’s publication, the Vatican would finally announce the much-anticipated opening of these “secret archives” in 2020.

The editors, Maria Anna Zumholz and Michael Hirschfeld, discuss significant forthcoming works on both von Faulhaber and Jaeger to account partly for the brevity of the studies here (13). And while there is a detailed chapter by Raphael Hülsbömer on Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli – later Pope Pius XII – and his relations with the German bishops, there is no attempt to integrate the episcopate into Vatican politics or consider the complicated, at times strained relationship between the wartime pope and the bishops as a collective. The editors justify this in part by referencing the closed archives covering the wartime pontificate of Pius XII; they could not have known that the year following this volume’s publication, the Vatican would finally announce the much-anticipated opening of these “secret archives” in 2020. Ruff begins with the assumption that both churches, Catholic and Protestant, share a compromised history within the Nazi state. He also acknowledges that both churches from 1945 to 1949 worked to polish their reputations: “Not wishing to further damage Germany’s reputation abroad …,” both Catholics and Protestants “elevated to orthodoxy the picture of the church triumphant, of clear-headed leaders valiantly resisting and the faithful unflinchingly following” (243). Not until the 1980s did historians of the Protestant Church seriously begin to redraw this rosy picture. However, Catholic behavior came under widespread attack already in the 1950s, “Doubts about the moral fitness of Catholic bishops, Cardinal Secretary of States and pontiffs of the Nazi era were cascaded before the public. They screamed from front-page headlines, the magazine covers of the most influential newsweeklies, the glossy pages of illustrated magazines and the best-seller lists in Germany and the United States.” Why did this happen? “This has been a guiding question for this book, since by almost all objective yardsticks, the German Protestant leadership left behind a more troubling record of collaboration than their Catholic counterparts” (244).

Ruff begins with the assumption that both churches, Catholic and Protestant, share a compromised history within the Nazi state. He also acknowledges that both churches from 1945 to 1949 worked to polish their reputations: “Not wishing to further damage Germany’s reputation abroad …,” both Catholics and Protestants “elevated to orthodoxy the picture of the church triumphant, of clear-headed leaders valiantly resisting and the faithful unflinchingly following” (243). Not until the 1980s did historians of the Protestant Church seriously begin to redraw this rosy picture. However, Catholic behavior came under widespread attack already in the 1950s, “Doubts about the moral fitness of Catholic bishops, Cardinal Secretary of States and pontiffs of the Nazi era were cascaded before the public. They screamed from front-page headlines, the magazine covers of the most influential newsweeklies, the glossy pages of illustrated magazines and the best-seller lists in Germany and the United States.” Why did this happen? “This has been a guiding question for this book, since by almost all objective yardsticks, the German Protestant leadership left behind a more troubling record of collaboration than their Catholic counterparts” (244). Susan Zuccotti is an established American scholar who has written a number of studies of the Holocaust, particularly dealing with events in France and Italy. Her latest contribution provides us with a well-researched biography of a little-known French Capuchin friar, Fr. Marie-Benoît, who was to play a significant role in rescuing Jews first in Marseilles in 1942 and then in Rome in 1943-4. Although he was to live for several decades after the war, his exploits were only recorded in French and remained largely unnoticed in remote French archives. Zuccotti was able to interview him in 1988 shortly before he died, but he was clearly a reticent witness, and it has taken her another twenty-five years to piece together his full story and to explore the determining factors which led him to play such an active role in assisting the Jewish refugees and victims of Nazi tyranny. The result is a portrait of a valiant and courageous priest whose witness in the cause of Christian-Jewish relations deserves to be better known to an English-speaking audience. So we can be grateful to Zuccotti for this helpful addition to the debate about how much (or how little) was done by various sectors of the Catholic Church to assist the Jewish victims of Nazism.

Susan Zuccotti is an established American scholar who has written a number of studies of the Holocaust, particularly dealing with events in France and Italy. Her latest contribution provides us with a well-researched biography of a little-known French Capuchin friar, Fr. Marie-Benoît, who was to play a significant role in rescuing Jews first in Marseilles in 1942 and then in Rome in 1943-4. Although he was to live for several decades after the war, his exploits were only recorded in French and remained largely unnoticed in remote French archives. Zuccotti was able to interview him in 1988 shortly before he died, but he was clearly a reticent witness, and it has taken her another twenty-five years to piece together his full story and to explore the determining factors which led him to play such an active role in assisting the Jewish refugees and victims of Nazi tyranny. The result is a portrait of a valiant and courageous priest whose witness in the cause of Christian-Jewish relations deserves to be better known to an English-speaking audience. So we can be grateful to Zuccotti for this helpful addition to the debate about how much (or how little) was done by various sectors of the Catholic Church to assist the Jewish victims of Nazism. Paul O’Shea is one of the small group of Australian scholars who have become interested in the Catholic response to the traumatic events of the twentieth century, and particularly in the career of Pope Pius XII, as he sought to deal with the crises brought on by the totalitarian regimes of Europe. Like all of his predecessors, O’Shea suffers the handicap that many of the relevant documents have yet to be released from the Vatican archives, so despite his assiduous survey of Pius’ earlier life as a Vatican diplomat and later as Cardinal Secretary of State, we still have to acknowledge the tentative evaluation of all hypotheses about his war-time policies, and especially about his so-called “silence” concerning the victimization of the Jews of Europe.

Paul O’Shea is one of the small group of Australian scholars who have become interested in the Catholic response to the traumatic events of the twentieth century, and particularly in the career of Pope Pius XII, as he sought to deal with the crises brought on by the totalitarian regimes of Europe. Like all of his predecessors, O’Shea suffers the handicap that many of the relevant documents have yet to be released from the Vatican archives, so despite his assiduous survey of Pius’ earlier life as a Vatican diplomat and later as Cardinal Secretary of State, we still have to acknowledge the tentative evaluation of all hypotheses about his war-time policies, and especially about his so-called “silence” concerning the victimization of the Jews of Europe.