Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 30, Number 3 (Fall 2024)

Review of Giuliana Chamedes, A Twentieth-Century Crusade: The Vatican’s Battle to Remake Christian Europe (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019). ISBN 978-0-674-98342-7.

By Martin Menke, Rivier University

In this useful volume, Giuliana Chamedes describes the Catholic Church’s efforts to resist what it considered the dangerous ideologies of the modern world. She presents not only communism and National Socialism as the enemies of faith, but in the most crucial contribution of the work, she demonstrates that the Church resisted and rejected what it perceived to be American liberalism and materialism. She argues that, to oppose liberalism and especially communism, the Church made common cause with fascist regimes. She describes these efforts as a crusade, which is an unusual choice of word, laden with historical and also contradictory meaning. Using the term “crusade” to refer to the attempted conquests of the Holy Land several centuries ago is problematic. The term is more appropriate if one defines a crusade as an organized effort by the Church to regain influence on the European continent. Chamades’ interpretation of the Vatican’s efforts to combat modern ideologies ever since Leo XIII wrote Rerum Novarum as part of an organized campaign to regain political and moral influence justifies the term “crusade.” Chamades, however, goes beyond the broad term “crusade” to argue for the existence of a Catholic “International,” a term suggesting a centrally-organized, conscious effort with national and regional branches. Instead, the sources indicate an effort that might better be described as a theme or leitmotif rather than an organized campaign. Thus, while Chamades demonstrates consistent anti-communist efforts by various Vatican offices, these efforts fall short of an institutionalized and centrally organized campaign. There is no evidence of an organized or institutionalized Catholic “International.” Nonetheless, the work has some interesting points to offer.

Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism.

Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism.

The author suggests that the papal peace plan of 1917 and the promulgation of the Code of Canon Law that same year constituted efforts to gain influence in international relations by reviving papal diplomacy. The Church sought to promote its values by integrating provisions of the new Code of Canon Law into concordats to curb the influences of socialism and liberalism. The church sought to retain legal control over marriages and education. Chamedes shows that this new papal diplomacy by concordat succeeded only when the country in question also considered such agreements advantageous. For example, the Baltic Republics and Poland believed the concordats affirmed their national sovereignty. The Church also usually conceded to the state some influence over appointing influential national church leaders. [44] When in 1925, the Vatican established a Polish metropolitan see at Vilnius, however, Lithuania broke off concordat negotiations before an authoritarian regime concluded a concordat in 1927. [62-63]

Chamedes discusses scholarly literature and sources referring to the “Catholic International” compared to the Communist International and similar organizations, but she does not fully define the term, nor does she provide evidence of a Catholic International. [6, 86] While the term “Catholic internationalism” describes the Church’s universalist claims well, the term “International,” especially when capitalized, suggests something much more formal and suggests a structure comparable to the Communist “International.” That idea suggests more centralized power over national churches than the papacy ever possessed. Also, the fascist regimes with which the Church cooperated – never unconditionally and rarely wholeheartedly – rejected internationalism, a contradiction that Chamedes does not address. In fact, in its propaganda, the National Socialist regime told a tale of secret Catholic ambitions to control the world. The closest the Church came to an open claim to world leadership was its vehement rejection of the League of Nations, another Wilsonian idea. Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI, declared the League superfluous since the Church was the one true global league. [55] With some justification, other Church officials denounced the League as a tool of the war’s victors to control international affairs.

Between the end of World War I and the early Cold War, Monsignor Eugenio Pacelli played an essential role in Vatican diplomacy, first as one of the editors of the Code of Canon Law, then as nuncio to Bavaria and Germany, then as Cardinal Secretary of State, and finally as Pope Pius XII. Chamades accurately narrates Pacelli’s turn to a fiercely anti-communist and more antisemitic position based on his experiences as nuncio in Munich during the revolutionary period 1918-1919. (80) Chamades suggests Pacelli embraced the popular notion of Judeo-Bolshevism and encouraged the Bavarian People’s Party, which had broken away from the (Catholic) German Center Party, to establish Bavaria as a base against the perils of communism [90]. Chamades stresses that Pacelli adopted this stance well before the Vatican relinquished hopes of achieving a modus operandi with the Soviet government in the later 1920s. Chamades argues that Pacelli urged his predecessor as Cardinal Secretary of State, Pietro Gasparri, to pursue an aggressive anti-communist agenda. [104]

While increasingly the Church focused on anti-communism, anti-liberalism remained a common denominator between the Church and fascist regimes. Chamades explains how Italian fascism, initially anti-clerical, changed course out of consideration that the Church was an enemy of communism. [96] Chamades emphasizes Mussolini’s early anti-liberal turn, which the anti-communist campaign later superseded. According to Chamades, the Church responded to communism and liberalism by promoting its model of an ideal civil society, organized around “Catholic Action,” a renewed attempt to tie Catholics to civic organizations arranged within a parochial, diocesan, and universal Catholic hierarchy. [112] Of all the early twentieth-century Vatican initiatives, Catholic Action was the most organized and institutional, though still largely ineffective in rallying the faithful. Catholic Action’s aims to organize all Catholics led to the Church’s first open conflict with Italian fascism, a conflict then repeated with all other authoritarian regimes.

Intending to resolve such differences, the Vatican began negotiating a concordat with fascist Italy. Pope and Duce each intended the subsequent Lateran Agreements of 1929, ostensibly concluded to resolve their conflicts, to advance their own interests, which led to continued tension. [117] Concordats were no longer measures to impose Catholic Canon Law and Catholic moral teaching on the state, but rather defensive agreements to secure existing rights. The Lateran Agreements gravely disappointed anti-fascist Catholic politicians such as Luigi Sturzo and Alcide de Gasperi. Chamades demonstrates that the financial terms of the Lateran Agreements, primarily their financial and bond payments by Italy to the Holy See, exposed the Vatican to global economic turmoil in new and devastating ways. [122] To put the Catholic social teaching of Leo XIII in Rerum Novarum in the context of the post-war world and the Great Depression, Pope Pius XI again related liberalism and socialism to one another as erroneous ideologies destined to lead the faithful astray. Discussing the aftermath of Quadragesimo Anno, Chamades again refers to a Vatican anti-communist “campaign.” The term “campaign” denotes organized and coordinated efforts. While Chamades cites the most relevant scholarly works before the establishment of the Secretariat for Atheism in the later 1930s, the argument lacks a smoking gun. She does not mention a meeting, correspondence, or institution that launched such a campaign. Yes, the Vatican’s efforts after Quadragesimo Anno no longer sought any accommodation with communist regimes, but there is no evidence of a campaign against communism. Instead, it seems as if an anti-communist Zeitgeist might be a better term than “campaign.” According to Vatican archival documents cited by Chamades, by 1931, Pope Pius XI determined that communism was the most dangerous enemy of the hour, but he did not launch an anti-communist campaign. [125] Chamades points out that Pacelli was the driving force behind the pope’s anti-communism, which by April 1932 had come to dominate the Holy See’s ideological concerns. [134] According to Chamades, a 1932 circular by Pacelli, now Cardinal Secretary of State, “proposed to launch an anticommunist campaign.” [125] Since the document is crucial to Chamades’ arguments, one wishes she had discussed it in more detail, especially regarding its consequences. What did Pacelli mean by the term “anti-communist campaign?” Again, a campaign requires organization and leadership. Did this ever come to be? Did Pacelli intend something like the creation of the Secretariat of Atheism? A later discussion of the “anti-communist campaign” provides no further explanation except to equate Catholic internationalism with the media “campaigns” of the 1930s. Missing is proof of any organized campaign. (132)

While Chamades correctly identifies anti-communism as the European hierarchy’s primary concern, she underestimates the Church’s continuing wariness of fascism, as for example with the German episcopate’s 1931 condemnation of fascism, to which she does not give sufficient attention. (138) Until the late 1920s, the Vatican had sought some accommodation with the Soviet regime and had devoted charitable aid to the regions stricken by the Russian Civil War. It is essential, however, to consider the Church’s growing anti-communism in connection with the Vatican’s increasing concern with Mussolini’s fascism and German National Socialism. Neither ideology developed in ways compatible with Catholic teaching. Furthermore, concerning the National Socialist rise to power, Chamades follows a familiar but deeply flawed argument when she claims it was an easy path from the March 1933 Enabling Act to the Concordat signed that July. All evidence, much of it available since the 1960s, proves how tortuous the negotiations were, and how the Vatican sought to gain every possible advantage. Chamades herself relies heavily on Vatican records, but not on all of them. Her use of the Vatican correspondence with papal nuncio in Berlin Cesare Orsenigo and the correspondence between Jesuit Superior General Wlodimir Ledochowski and the Vatican is beneficial. Still, she ignores other Vatican archival records relating to such processes as the Reich concordat negotiations. In particular, it would have been useful had she used the documents published by Father Ludwig Volk, SJ, and Alfons Kuppers. (Ludwig Volk, Kirchliche Akten über die Reichskonkordatsverhandlungen 1933. Mainz: Mathias-Grunewald-Verlag, 1969. Alfons Kupper, Staatliche Akten über die Reichskonkordatsverhandlungen 1933. Mainz: Mathias-Grunewald-Verlag, 1969).

While the fascist governments in Berlin and Rome violated the concordats as much as they observed them, Chamades shows that forces in the Vatican now called for a single-minded focus on anti-communism. In late 1933, Jesuit Superior General Wlodimir Ledochowski convinced Pius XI to establish a “Secretariat on Atheism.” [146] Chamades explains the considerable public relations activity of the Secretariat across Europe; one wonders how effective the Secretariat was in influencing not only members of the hierarchy but also the faithful. How much was the average Catholic aware of this centrally coordinated campaign? Furthermore, while Chamades convincingly shows the extent of the Vatican’s anti-communist “campaign” across the continent, one has to wonder how much fascist regimes desired to encourage widespread media work by the Church. Furthermore, the question again arises of how organized and centralized efforts must be to qualify as a campaign. It seems as if different Vatican offices pursued anti-communist efforts because they knew these were in line with the leitmotif of anti-communism, not because someone centrally coordinated their efforts.

While one might think that the establishment of the Secretariat marked the end of anti-fascist concerns, Chamades acknowledges that the Church in the early 1930s was preparing a new Syllabus of Errors to condemn both communism as well as fascism. The Church abandoned this thrust not only because of the opposition of Ledochowski, but also under the influence of the Popular Front victory in Spanish elections. [172-173] Alongside many scholars, Chamades criticizes the relatively weak language in the 1937 encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge and notes, in contrast, that in the anti-communist encyclical Divini Redemptoris released five days later, the Vatican pulled no punches. Following the condemnation of communism in Mexico in Firmissimam Constantiam, these three encyclicals made clear that the Church now considered communism, not totalitarianism, to be the greatest threat of the twentieth century. While much of the narrative recounted here is well known, Chamades provides a useful summary and some helpful distinctions. Her global perspective is helpful.

Once the newly elected Pius XII and those around him suppressed the draft of Pius XI’s encyclical condemning racism outright and when, a year later, World War Two broke out, the Church seemed firmly on the side of all anti-communist forces. Comparing the Church’s position in World War II to that in World War I, Chamades notes that the Church had virtually no allies in the second war and that the Vatican developed no significant diplomatic activity, an assessment surprising to any historian familiar with the Vatican during that time. Faced with Pius XII’s supposed inaction, Chamades argues an internal opposition arose within the Church. When Cardinal Pacelli became Pope Pius XII, however, the Vatican reaffirmed its centralizing and hierarchical approach to church leadership, in which there was little room for dissent. The outbreak of war, however, limited the ability to engage in any efforts to combat communism and subjected the Church to an increasingly assault by National Socialism. Both to those hoping for a pontiff more critical of fascism as well as for the Catholic leaders of newly invaded Poland, the first encyclical of Pius XII, Summi Pontificatus, proved a disappointment because it lacked a clear condemnation of the German invasion and its consequences. Those Catholics whom the Vatican’s inaction disappointed began to demand greater Catholic engagement for peace. Men like Don Luigi Sturzo, Jacques Maritain, and Henri de Lubac forcefully made their case in whatever press would publish their work. Additional efforts by Sturzo and Maritain, whom Chamades calls Catholic internationalists, to convince Pius XII to take a more active stand failed. This inspired a new type of Catholic activist, those committed to a peace based on Christian democracy.

Chamades demonstrates that Vatican attitudes shifted after the German invasion of the Soviet Union and the U.S. entry into the war. [220-222] The pope did not endorse the German invasion. Furthermore, he agreed to urge the American bishops to support the lend-lease agreement. Her discussion of the papacy’s response to the Shoah is limited to a few pages in which she notes that bishops informed the Vatican of the deportations of Jews and that the Vatican could have done far more to help Jews. On the one hand, this brevity is a wise choice, given the vast and contradictory scholarly literature on the subject. Chamades could have developed the complexity of her argument. Does she consider national socialist antisemitism an instance of concurrence between longstanding Catholic antisemitism and a modern ideology? On the other hand, given the German promotion of a “crusade against Bolshevism” and the thesis she is trying to prove, a more detailed discussion of the Catholic response to the Shoah would have been helpful. Chamades points out, that the Vatican did not welcome the public appeals for an outspoken condemnation of National Socialist atrocities. [228] Nonetheless, Catholic dissidents, as Chamades calls them, continued to speak up and began to organize to create a post-war world based on Christian principles, especially on a commitment to freedom and peace. Eventually, these would become the post-war Christian Democrats. She points out that “after the war, the papacy also agreed to work with Europe’s new Christian Democratic parties” [236] and even endorsed the United Nations, part of the Vatican’s general shift to greater cooperation and engagement with other civil society organizations. And yet, the Vatican’s new understanding of democracy was not one of total liberty but of freedom based on Catholic moral teaching. A more probing analysis of how, why, and with what consequences the war transformed the Vatican’s values would have enriched the work.

Beginning in 1945, the Vatican feared that the Western allies were too accommodating of the Soviet Union and were willing to hand over Eastern Europe. Chamades points out that, in contrast to the Church’s wartime failure to share information about atrocities in Eastern Europe, it now broadly shared all news of communist persecution of the Church and the faithful. [245] Furthermore, Pope Pius XII sought the aid of the United States to combat the growth of communist parties in Western Europe, which represented an abandonment of the Church’s interwar anti-liberal criticism of the United States. Despite these tactical changes, the Church envisioned a Europe formed of Christian states. It became suspicious of Christian Democratic movements when these, building on the wartime criticism within the Church, insisted on their independence from the Catholic hierarchy. [250] Chamades might have noted that the interwar Catholic parties also jealously guarded their independence from the Vatican. She claims that a new Christian Democratic International arose from the discussions of post-war Christian Democratic groups, but again, there was no such organization.

Chamades shows that, in the postwar era, the Vatican could not exercise the influence which it had expected in a post-war world. A brief period of goodwill towards the United States and the new Christian Democrats soon gave way to criticism and mistrust of both as too independent in the case of the Christian Democrats and too rooted in anti-Catholicism in the case of the United States. As Chamedes herself shows, the Vatican feared that Christian Democracy was insufficiently immune to communist. Also, Christian Democratic political parties and actors proved increasingly independent of the Vatican. The Vatican again became critical of the United States. [282] According to Chamedes, the resurgence of American Protestant anti-Catholicism and the break in U.S. diplomatic representation to the Vatican contributed to a revival of Vatican anti-Americanism, expressed as fears of American hegemony and materialism. This seemingly left the Vatican without political allies.

In the 1950s, new criticisms arose against the Vatican. The Church’s failure to side with anti-imperialist movements in the developing world led to further alienation. [286] Another challenge to Church authority and legitimacy arose via the accusations by journalists, scholars, and others of Church complicity with the National Socialist regime. In many ways, the 1950s marked the nadir of Church influence in Europe. Chamades argues that the Second Vatican Council represented Pope John XXIII’s recognition that the influence of the Vatican and of the broader over the faithful in private and public life was waning, and that the policies of his predecessors had led the Church to a dead-end.

Consequently, as Chamades convincingly explains, the Second Vatican Council overthrew much of what the Vatican leadership had considered self-evident about Church-state relations and about Church power and authority. She argues that the new Apostolic Constitutions, such as Lumen Gentium and Dignitatis Humanae, on the one hand, attempted to meet the expectations of many who demanded change in the post-war Church while at the same time proving unable to relinquish dogmatic claims to represent the one true path to salvation. Chamedes argues that Gaudium et Spes, the constitution explaining how Catholics and their Church should function in a modern, pluralistic society, constituted a rejection of the concordat strategy employed during the first half of the twentieth century. [301] Instead, the Second Vatican Council suggested a way forward in cooperation with other faiths and other ideologies as long as they authentically promoted human welfare.

In the conclusion, Chamedes argues that the Vatican’s policies of the 1930s sowed the seeds for the demand for reform that became vocal after 1945. The Church’s reform efforts of the 1960s came too late; too many Catholics were already heading out the door. [312] Chamades argues that Humanae Vitae accelerated the exodus. In contrast, Pope John Paul II promoted Church leaders who were critical of the Second Vatican Council and more comfortable with cold-war anti-communism. Despite this decline in Vatican authority over the faithful, Chamedes argues that the Church remains a powerful actor on the world stage thanks to its moral pulpit.

Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less.

Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less. The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position.

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position. Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true.

Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true. Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background.

Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background. Helge-Fabien Hertz’s weighty dissertation (2021) from Kiel University, supervised by Rainer Hering (Schleswig- Holstein State Archives), Peter Graeff and Manfred Hanisch (both from Kiel University), now joins this recent research tradition. The study consists of a group biography of the 729 pastors who worked in the Schleswig-Holstein state church shortly before and during the Nazi era (1930-1945). The study is based on a broad range of sources: the clergymen’s personal files were evaluated; in addition, the author has consulted sermons and confirmation lesson plans, denazification files, the relevant state church archive files on the Kirchenkampf, documents on NSDAP membership in the Berlin Federal Archives, and a wealth of contemporary lectures, articles, letters, diaries. Hertz uses a sophisticated set of social-science methods to operationalize the exorbitant amount of data from this large group of people (quantification of “attitudes” and “actions” with the aid of indicators) and to present it using a variety of statistics, diagrams, etc. One must admit at the outset, it is not always easy to keep track of the whole given the extreme complexity of the work’s organization into “parts”, “sections”, “chapters”, and so on.

Helge-Fabien Hertz’s weighty dissertation (2021) from Kiel University, supervised by Rainer Hering (Schleswig- Holstein State Archives), Peter Graeff and Manfred Hanisch (both from Kiel University), now joins this recent research tradition. The study consists of a group biography of the 729 pastors who worked in the Schleswig-Holstein state church shortly before and during the Nazi era (1930-1945). The study is based on a broad range of sources: the clergymen’s personal files were evaluated; in addition, the author has consulted sermons and confirmation lesson plans, denazification files, the relevant state church archive files on the Kirchenkampf, documents on NSDAP membership in the Berlin Federal Archives, and a wealth of contemporary lectures, articles, letters, diaries. Hertz uses a sophisticated set of social-science methods to operationalize the exorbitant amount of data from this large group of people (quantification of “attitudes” and “actions” with the aid of indicators) and to present it using a variety of statistics, diagrams, etc. One must admit at the outset, it is not always easy to keep track of the whole given the extreme complexity of the work’s organization into “parts”, “sections”, “chapters”, and so on. Bergen first asks what chaplains knew about the annihilation of the Jews and whether or not they sought to intervene. Working with letters individual chaplains sent to their bishops, friends, and family, official Wehrmacht reports on the chaplaincy, and more, Bergen paints an expected but devastating picture. Bergen demonstrates that the chaplains she studied were committed to their pastoral duties as they understood them. The chaplains celebrated religious services, counseled individual soldiers, and accompanied soldiers sentenced to death by a German court-martial on their final way. Before the war, Bergen shows, the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front. As Lauren Faulkner Rossi showed in her work Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation, the chaplains were constantly fighting efforts by the national socialist regime to curtail their activities, including the wartime decision not to replace chaplains killed or wounded in action with other chaplains and appoint Nationalsozialistische Führungsoffiziere (NSFO), national socialist leadership officers, instead. (Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015)). Beyond the fear of the NSFO, Bergen shows the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front.

Bergen first asks what chaplains knew about the annihilation of the Jews and whether or not they sought to intervene. Working with letters individual chaplains sent to their bishops, friends, and family, official Wehrmacht reports on the chaplaincy, and more, Bergen paints an expected but devastating picture. Bergen demonstrates that the chaplains she studied were committed to their pastoral duties as they understood them. The chaplains celebrated religious services, counseled individual soldiers, and accompanied soldiers sentenced to death by a German court-martial on their final way. Before the war, Bergen shows, the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front. As Lauren Faulkner Rossi showed in her work Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation, the chaplains were constantly fighting efforts by the national socialist regime to curtail their activities, including the wartime decision not to replace chaplains killed or wounded in action with other chaplains and appoint Nationalsozialistische Führungsoffiziere (NSFO), national socialist leadership officers, instead. (Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015)). Beyond the fear of the NSFO, Bergen shows the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front. The main source material that Madigan draws upon comes from the pontificate of Pius XI (1922-1939), the records of which only became available in 2006. But the story begins in the Risorgimento in the mid-nineteenth century and the triumph of a new liberal order that brought religious tolerance in the form of openness to non-Catholic religious confessions. Into this environment emerged evangelical Protestant missionaries from England and America, many of whom were Italian immigrants who had converted to a form of Protestantism in their new country and later returned to Italy. Methodists, Baptists, Pentecostals, the Salvation Army, the YMCA, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Adventists brought with them an evangelical style of preaching that emphasized conversion and an array of educational, medical, and social programs that benefited the Italian lower classes and peasantry. The fact that this Protestant missionary activity mapped onto a global trend of Protestant expansion in this period was all the more concerning for the Vatican, especially after World War I and the growth of Anglo-American power.

The main source material that Madigan draws upon comes from the pontificate of Pius XI (1922-1939), the records of which only became available in 2006. But the story begins in the Risorgimento in the mid-nineteenth century and the triumph of a new liberal order that brought religious tolerance in the form of openness to non-Catholic religious confessions. Into this environment emerged evangelical Protestant missionaries from England and America, many of whom were Italian immigrants who had converted to a form of Protestantism in their new country and later returned to Italy. Methodists, Baptists, Pentecostals, the Salvation Army, the YMCA, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Adventists brought with them an evangelical style of preaching that emphasized conversion and an array of educational, medical, and social programs that benefited the Italian lower classes and peasantry. The fact that this Protestant missionary activity mapped onto a global trend of Protestant expansion in this period was all the more concerning for the Vatican, especially after World War I and the growth of Anglo-American power. At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press.

At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press. In 2015, a movement arose to repeal Gröber’s honorary town citizenship based on impressions contemporaries had of his speeches and his supposed support for the National Socialist regime, especially in 1933-34. In response, Mühleisen offers a differentiated analysis of Gröber and avoids definite judgment where ambiguity remains. Mühleisen also avoids moral judgment, which he argues is not the purpose of this historical study. He questions whether or not one can weigh moral accomplishments against moral failings to arrive at a “bottom line” judgment. In a fairly balanced account, Mühleisen discusses several lapses in judgment by Gröber, such as his decision to join the SS “booster club.” Also, Mühleisen notes that Gröber’s early public support for the regime confused the laity. While incomprehensible today, some have described membership in this organization as a protection racket. Similarly, in the first months of the new regime, Gröber emphasized his willingness to work with the new government authorities. Possible evidence for this is the Gestapo’s fear of Gröber’s fundamental opposition to the regime.

In 2015, a movement arose to repeal Gröber’s honorary town citizenship based on impressions contemporaries had of his speeches and his supposed support for the National Socialist regime, especially in 1933-34. In response, Mühleisen offers a differentiated analysis of Gröber and avoids definite judgment where ambiguity remains. Mühleisen also avoids moral judgment, which he argues is not the purpose of this historical study. He questions whether or not one can weigh moral accomplishments against moral failings to arrive at a “bottom line” judgment. In a fairly balanced account, Mühleisen discusses several lapses in judgment by Gröber, such as his decision to join the SS “booster club.” Also, Mühleisen notes that Gröber’s early public support for the regime confused the laity. While incomprehensible today, some have described membership in this organization as a protection racket. Similarly, in the first months of the new regime, Gröber emphasized his willingness to work with the new government authorities. Possible evidence for this is the Gestapo’s fear of Gröber’s fundamental opposition to the regime. In the volume under review, the contributions of different generations of historians reflect this evolution. The subject is Cardinal Lorenz Jaeger, Archbishop of Paderborn, 1941-1973. Before becoming archbishop, Jaeger had served as a regular army officer in World War One, then entered the seminary. He served as Dortmund’s youth pastor and teacher during the inter-war period. Upon the outbreak of World War II, Jaeger immediately volunteered as a military chaplain. Both in his capacity as a teacher and as a military chaplain, he had to pass background checks by Nazi authorities. Various contributors, however, note that, during Jaeger’s episcopal ordination process, the regime’s security authorities reported fundamental misgivings about his appointment. As early as 1935, authorities noted his rejection of Alfred Rosenberg’s Mythos des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. The Sicherheitsdienst [SD] and regional NSDAP offices considered him a threat to the regime. At the ministerial level, both sides tried to de-escalate conflicts in the broader context of the regime’s relations with the Catholic Church, especially in episcopal ordinations. So the Reich Minister of Church Affairs, Hans Kerrl, approved Jaeger’s ordination as Archbishop of Paderborn.

In the volume under review, the contributions of different generations of historians reflect this evolution. The subject is Cardinal Lorenz Jaeger, Archbishop of Paderborn, 1941-1973. Before becoming archbishop, Jaeger had served as a regular army officer in World War One, then entered the seminary. He served as Dortmund’s youth pastor and teacher during the inter-war period. Upon the outbreak of World War II, Jaeger immediately volunteered as a military chaplain. Both in his capacity as a teacher and as a military chaplain, he had to pass background checks by Nazi authorities. Various contributors, however, note that, during Jaeger’s episcopal ordination process, the regime’s security authorities reported fundamental misgivings about his appointment. As early as 1935, authorities noted his rejection of Alfred Rosenberg’s Mythos des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. The Sicherheitsdienst [SD] and regional NSDAP offices considered him a threat to the regime. At the ministerial level, both sides tried to de-escalate conflicts in the broader context of the regime’s relations with the Catholic Church, especially in episcopal ordinations. So the Reich Minister of Church Affairs, Hans Kerrl, approved Jaeger’s ordination as Archbishop of Paderborn. First, Tarach uses National Socialist propaganda for his analysis and demonstrates that many Nazi stereotypes came directly from the Christian context: the Jews as children of the devil, the betrayal by Judas Iscariot, etc. In the middle of the twentieth century, those images were well known by Christian people. The murder of Jesus of Nazareth remains the central element of Christian anti-Semitism up to modern anti-Semitism and forms the background of all persecutions of the Jews. Even today, in parts of Eastern Europe, the Jew is symbolically burned at Easter because he murdered Christ. We fully agree with the author’s statement that the New Testament already spread the first anti-Semitic conspiracy theory: the Jew as murderer of God (48). The desire for the annihilation of all Jews, which was already virulent before National Socialism, is based precisely on this motive: a danger emanates from the Jews. That is why the extermination of the Jews is also seen as self-defense. At this point, the author could, or even should, have referred to the minutes of the Wannsee Conference to support his arguments. In it, the motivation for the extermination of the Jews in Europe by the National Socialists as an act of self-defense is particularly clearly expressed.

First, Tarach uses National Socialist propaganda for his analysis and demonstrates that many Nazi stereotypes came directly from the Christian context: the Jews as children of the devil, the betrayal by Judas Iscariot, etc. In the middle of the twentieth century, those images were well known by Christian people. The murder of Jesus of Nazareth remains the central element of Christian anti-Semitism up to modern anti-Semitism and forms the background of all persecutions of the Jews. Even today, in parts of Eastern Europe, the Jew is symbolically burned at Easter because he murdered Christ. We fully agree with the author’s statement that the New Testament already spread the first anti-Semitic conspiracy theory: the Jew as murderer of God (48). The desire for the annihilation of all Jews, which was already virulent before National Socialism, is based precisely on this motive: a danger emanates from the Jews. That is why the extermination of the Jews is also seen as self-defense. At this point, the author could, or even should, have referred to the minutes of the Wannsee Conference to support his arguments. In it, the motivation for the extermination of the Jews in Europe by the National Socialists as an act of self-defense is particularly clearly expressed. The book is divided into four main chapters – I. Christian Denominations and Nazism; II. New Faith Movement; III. Jews, Antisemitism and “Kristallnacht”; IV. War, Christians and the Holocaust – with varying numbers of sub-chapters. Instead of an introduction, Gailus precedes the chapters with a short section entitled “Concepts, Questions, Problems” in which he introduces his topic and the central question of his study: “What did the Germans believe in during the Hitler era?” (p. 8). Given it has been shown that 95% of Germans belonged to a Christian denomination during the Nazi regime and the “astonishing mixture of individual faiths” (p. 10) and “hybride Doppelgläubigkeiten” that Gailus has identified – in particular, those blending Christian faith and Nazi confession – the study sets out to analyse the traditional Christian characteristics in relation to the reshaping and partial new imprints of religiosity that occurred during the “Third Reich” and, thereby, offer an interpretation of the Nazi era in terms of the history of religion. The author proposes that the Nazi era was a “time of faith”, “Gläubige Zeiten” with a “high conjuncture” of faith and faithfulness (p. 11). Methodologically speaking, Gailus claims to look from above, from a “bird’s eyes view” (p. 11), though it should be noted that his altitude varies significantly throughout the book. Given his own extensive research, he flies in very close to Protestantism, while remaining more distant from Catholicism, the perspective on which is primarily literature-based and, therefore, more superficial. Gailus also flies particularly close to Berlin, the geographical focus of his own research and most of the examples he cites.

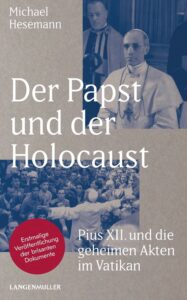

The book is divided into four main chapters – I. Christian Denominations and Nazism; II. New Faith Movement; III. Jews, Antisemitism and “Kristallnacht”; IV. War, Christians and the Holocaust – with varying numbers of sub-chapters. Instead of an introduction, Gailus precedes the chapters with a short section entitled “Concepts, Questions, Problems” in which he introduces his topic and the central question of his study: “What did the Germans believe in during the Hitler era?” (p. 8). Given it has been shown that 95% of Germans belonged to a Christian denomination during the Nazi regime and the “astonishing mixture of individual faiths” (p. 10) and “hybride Doppelgläubigkeiten” that Gailus has identified – in particular, those blending Christian faith and Nazi confession – the study sets out to analyse the traditional Christian characteristics in relation to the reshaping and partial new imprints of religiosity that occurred during the “Third Reich” and, thereby, offer an interpretation of the Nazi era in terms of the history of religion. The author proposes that the Nazi era was a “time of faith”, “Gläubige Zeiten” with a “high conjuncture” of faith and faithfulness (p. 11). Methodologically speaking, Gailus claims to look from above, from a “bird’s eyes view” (p. 11), though it should be noted that his altitude varies significantly throughout the book. Given his own extensive research, he flies in very close to Protestantism, while remaining more distant from Catholicism, the perspective on which is primarily literature-based and, therefore, more superficial. Gailus also flies particularly close to Berlin, the geographical focus of his own research and most of the examples he cites. The most important contribution of Hesemann’s work is its exhaustive collection of all evidence and arguments that portray the pope’s record in a positive light. A frequently cited problem was the vague and diplomatic language used in the pope’s statements and writings; Hesemann points to contemporary sources that clearly understood the pope’s intent. Referring to Pius’ first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, which includes a reminder about human fraternity and about the right of the victims of war and racism to human compassion, Hesemann points to the New York Times, which reported that the pope “condemned dictators, those who break international agreements, and racism.” Furthermore, the Times reported that while such a condemnation had been expected, “only few observers had expected the condemnation to be so clear and unequivocal” (104). Hesemann’s evidence suggests that Pius was not only not silent but that readers understood his guarded speech as he intended.

The most important contribution of Hesemann’s work is its exhaustive collection of all evidence and arguments that portray the pope’s record in a positive light. A frequently cited problem was the vague and diplomatic language used in the pope’s statements and writings; Hesemann points to contemporary sources that clearly understood the pope’s intent. Referring to Pius’ first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, which includes a reminder about human fraternity and about the right of the victims of war and racism to human compassion, Hesemann points to the New York Times, which reported that the pope “condemned dictators, those who break international agreements, and racism.” Furthermore, the Times reported that while such a condemnation had been expected, “only few observers had expected the condemnation to be so clear and unequivocal” (104). Hesemann’s evidence suggests that Pius was not only not silent but that readers understood his guarded speech as he intended.