Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 30, Number 4 (Winter 2024)

Review of Marshall J. Breger and Herbert R. Reginbogin, eds., The Vatican and Permanent Neutrality (Lanham, Boulder, New York, and London: Lexington Books, 2022). ISBN: 978-1-7936-4216-5

By Gerald J. Steinacher, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Permanent neutrality is a key concept for understanding the policies and teachings of the Holy See over the last 100-plus years. It is crucial for comprehending Vatican decision-making. For anyone interested in the history of the Catholic Church and the papacy, a key question in historical analysis is the motivation behind their actions, specifically the underlying theological or ideological factors. This is especially relevant in the context of the controversial discussions surrounding not only World War II but also the Cold War. The volume The Vatican and Permanent Neutrality, edited by Marshall J. Breger and Herbert R. Reginbogin, offers rich insights and material for further thought on this important topic, revealing a wide range of expertise and diverse perspectives from scholars of church history.

Breger rightly notes that following World War II, neutrality had a negative connotation and was often seen as a form of collaboration with the Nazis. Countries like Switzerland, and to some extent Sweden, did not emerge from the war with their reputations fully intact. Consequently, for many years, Vatican neutrality has received little attention in academic literature. This volume, which spans from 1870 to 2020, helps to close that gap by examining various aspects of the Vatican’s neutrality over these 150 years. However, the main focus is on the Vatican’s neutrality as defined in the Lateran Pacts of 1929, which also established the city-state. Breger states the goal of the project thus: “This book will consider the interplay between two normatively disparate subjects – the concept of neutrality in international law and the concept of the Vatican as a neutral actor in international relations” (Breger xii). This review will provide a general overview of the volume, highlighting a selection of the thirteen essays rather than examining each one in detail. I will focus primarily on essays that fall more closely in my own research purview, which deals with Fascism, WWII and the immediate postwar years.

Breger rightly notes that following World War II, neutrality had a negative connotation and was often seen as a form of collaboration with the Nazis. Countries like Switzerland, and to some extent Sweden, did not emerge from the war with their reputations fully intact. Consequently, for many years, Vatican neutrality has received little attention in academic literature. This volume, which spans from 1870 to 2020, helps to close that gap by examining various aspects of the Vatican’s neutrality over these 150 years. However, the main focus is on the Vatican’s neutrality as defined in the Lateran Pacts of 1929, which also established the city-state. Breger states the goal of the project thus: “This book will consider the interplay between two normatively disparate subjects – the concept of neutrality in international law and the concept of the Vatican as a neutral actor in international relations” (Breger xii). This review will provide a general overview of the volume, highlighting a selection of the thirteen essays rather than examining each one in detail. I will focus primarily on essays that fall more closely in my own research purview, which deals with Fascism, WWII and the immediate postwar years.

The volume’s chapters are mostly arranged chronologically. Part 1 examines the period from the end of the Papal States to the Vatican (1870–1929), with contributions by John F. Pollard, Kurt Martens, and Maria d’Arienzo. Pollard explains that, for centuries prior, the Church ruled over extended territories in central Italy, which the pope was determined to protect and expand. The “Vicar of Christ” in those centuries was usually neither neutral nor impartial nor peaceful. Military alliances were forged, and armies were recruited, including the now-famous Swiss troops. Popes and their families on the papal throne, such as the notorious Borgias in the 16th century, pursued wars and conquests, like other principalities in the Italian peninsula.

As in other parts of Europe and Latin America, nationalism in the nineteenth century surged through Italy. Backed by the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont, Italian nationalists sought to establish an Italian ethnic nation-state, which became a reality in 1861, with Turin as its first capital. Protected by French troops, the Papal States resisted until 1870, when Italian forces seized Rome by force. With Rome now the capital of Italy, the Holy See was left without any territory, prompting the pope to famously declare himself the “Prisoner in the Vatican.” Nevertheless, several powers continued to recognize the Holy See as sovereign and maintained diplomatic relations. For decades after 1870, the tensions between the Catholic Church and the constitutional liberal Italian monarchy remained unresolved and relations were often strained.

Claims of permanent neutrality toward all nations and the Holy See as a “peaceful sovereign” were emphasized by Vatican diplomats as early as the Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815. During World War I, Pope Benedict XV (1914–1922) became known as “the great neutral.” Practical considerations played a role, as Catholics fought on both sides of the front. Pollard shows that the pope also stayed neutral when it came to accusations of war crimes committed by Russia as well as Germany. “To have pronounced one way or another on alleged war crimes could inevitably have compromised the Vatican’s claims to neutrality and impartiality, so in public, Benedict limited himself to generic condemnations of all atrocities” (10). Pollard’s point is well taken, as this arguably set a precedent for the Holy See’s position during World War II. After WWI, the Vatican also tried to stay neutral, and when new nation-states and borders emerged, the diocesan geography needed redrawing, as Kurt Martens shows.

In 1929, the Holy See negotiated an agreement with the Italian government, then under Benito Mussolini, consisting of two parts: the Lateran Treaty and a concordat, collectively referred to as the Lateran Pacts. The Church was compensated for the loss of territory, regained its status as an independent, sovereign state (Vatican City), and declared its permanent neutrality. Maria d’Arienzo reminds us that there is a key distinction when it comes to the Vatican as a city-state: The Vatican is not a nation-state but rather a state administration that was designed to provide a basis for the universal mission of the papacy (Maria d’Arienzo 45). Article 24 of the Lateran Pacts creating the Vatican city-state in 1929 states, “The Holy See declares that it desires to take, and shall take, no part in any temporal rivalries between other states, nor in any international congresses called to settle such matters, save and except in the event of such parties making a mutual appeal to the pacific mission of the Holy See, the latter reserving in any event the right of exercising its moral and spiritual power” (quoted in Brown-Fleming 106). This text and its interpretation lie at the heart of the volume and its discussions that focus on Vatican neutrality: how it has been understood and whether it has changed over time, if at all. As Pollard points out, this is where the history of Vatican neutrality truly begins.

Part II, focusing on the “long Second World War: 1931-1945,” with contributions by Lucia Ceci, Pascal Lottaz, and Suzanne Brown-Fleming, could also be titled “Neutrality [Put] to the Test.” This is the title Ceci chose for her chapter on the Vatican and the Fascist wars of the 1930s. She points out that the 1929 Lateran Pacts was “an agreement signed with an authoritarian government with totalitarian ambitions” (Ceci 63). Both the Italian state as well as the Vatican believed that a modus vivendi would be possible. The pope officially granted the state temporal power over Rome, but the state ceded sovereignty in matters of marriage and teaching. Mussolini celebrated this reconciliation between Italy and the Holy See as a great achievement. The Church, too, was hopeful, as Ceci states, that the Fascist state was “catholicizable” and would cement a “Catholic nation” (Ceci 65).

Mussolini’s war of aggression in Ethiopia (1935–36/41)[1] and his military intervention in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), as well as the Italian Racial Laws (1938), put the Vatican’s declared neutrality to an early test. The papacy faced immense pressure to endorse Mussolini’s Ethiopian war; however, Ceci states that Pius XI was absolutely opposed to this Fascist war of conquest (68). Meanwhile, Italian Catholic bishops and clergy went above and beyond to show their support for Mussolini’s campaign. When it came to Italian laws against Jews, the pope limited his interventions to get exceptions for baptized Jews.

Behind the scenes, Pope Pius XI authorized the drafting of an encyclical letter condemning racism and modern antisemitism. Suzanne Brown-Fleming highlights the encyclical Humani Generis Unitas [“Unity of the Human Race”], which was prepared at Pius XI’s request in 1938 but was never released to the public. The encyclical emphasized that Catholics should not remain silent in the face of Jewish persecution. However, when Pius XII ascended to the papacy in 1939, he chose to shelve this encyclical (Brown-Fleming 105). Only a few months later, World War II broke out. Not unlike Pope Benedict XV during WWI, Pius XII also attempted to maintain neutrality and guide the Church through the storm that engulfed the world. During and after the war, particularly regarding the atrocities of the Holocaust, Pius XII was accused of silence and a lack of moral guidance. In the face of the Holocaust, why did the Holy See not use its “right to exercise its moral and spiritual power,” as enshrined in the Lateran Pacts? The heated debate over the pope’s responses to the Holocaust has been at the center of discussions for decades. The challenges faced by the universal Catholic Church during World War II included mass atrocities occurring not only in Europe but also in Asia, as discussed by Pascal Lottaz about “Vatican diplomacy and Church realities in the Philippines during World War II”. Pius XII tried to be neutral, but at the same time worked on a modus vivendi with the Japanese.

Brown-Fleming focuses on the immediate postwar years and examines the Vatican’s clemency appeals for Nazi war criminals on trial, drawing from several case studies in the Vatican archives. One well-known case is that of Oswald Pohl, who oversaw Nazi slave labor operations and was sentenced to death at one of the Nuremberg trials. The Holy See and German bishops went to great lengths to save the life of this mass murderer, who had converted to Catholicism while in prison. The Church’s stance on neutrality and “forgiveness” after World War II—exemplified by the interventions of the pope’s envoy in Germany, US Bishop Aloisius Muench, and the postwar Allied military government in Germany—reflected a tendency to forgive perpetrators and quickly forget the victims. This attitude was also intertwined with strong anti-communist sentiments. The broader question raised in this volume concerns Vatican neutrality, and this has particular significance in the context of papal aid for Nazi war criminals. As I have shown in Nazis on the Run and elsewhere, much of the Vatican’s efforts on behalf of Nazi perpetrators and their collaborators did not have leniency as the primary goal. Instead, these efforts were often intended to secure impunity through generous amnesties or even assistance in escape.[2] Such actions not only hindered Allied efforts toward postwar justice but also compromised Vatican neutrality.

Pius XII could be very undiplomatically direct when it came to confronting communism, ideologically and otherwise. For example, Piotr H. Kosicki details the Holy See’s role in the crucial Italian parliamentary election of 1948, where a victory for the left-wing alliance of communists and socialists was a realistic possibility. The “Civic Committees,” organized by Church-run Catholic Action, clearly aligned with the Christian Democrats (DC) and significantly influenced the election outcome. These committees played a pivotal role for the Christian Democrats by orchestrating a propaganda campaign against the communists and socialists. Concluding his chapter, Kosicki shows that the “lonely Cold War of Pius XII”[3] shifted to the “Vatican Ostpolitik” after the pope’s death in 1958. This Ostpolitik involved the normalization of relations with the highest levels of communist parties and states, with Yugoslavia being a prominent example.

Árpád von Klimó and Margit Balogh present the case of a widely forgotten story in public memory: the saga of Cardinal Mindszenty of Hungary. He spent fifteen years trapped in the U.S. Embassy in Budapest, a fascinating chapter of Cold War history. In the last part of this volume, on the post-Cold War period of 1990–2020, Massimo Faggioli explains how, after the Cold War, the Vatican adopted a policy of “positive neutrality,” engaging on new social and political levels. Luke Cahill looks at the Vatican’s outreach to Saddam Hussein and Bashar al-Assad in order to aid war victims. Maryann Cusimano Love analyzes the Church’s theological stance against nuclear weapons. In relation to just war theory, Saha Matsumoto discusses how, with the end of the Cold War, the Church felt free to oppose all nuclear weapons, no longer constrained by the “Communist menace.” Herbert Reginbogin concludes the volume in Chapter 13 by addressing the Vatican’s responses to scandals in the Church, such as money laundering, sexual abuse, and its efforts to repair historical wrongs.

To conclude, despite some minor shortcomings—including repetitive quotes and repetitions when explaining the Lateran Pacts as well as the chronology of chapters in some cases (e.g., Maria d’Arienzo’s outstanding chapter feels somewhat out of place in Part I, as much of it discusses post-1945 issues)—this volume is an excellent contribution. It presents different views and interpretations on the theme of “the Vatican and permanent neutrality” over the course of the last 150 years. The balanced contributions make the volume thought-provoking and invite further exploration of this fascinating topic. In a world where neutrality seems to be under strain—evident in Sweden and Finland recently abandoning their tradition of neutrality to join NATO—Austria’s ongoing discussions about its own tradition of “permanent neutrality” reflect the challenges faced by the once-neutral bloc of nations during the Cold War. The Vatican and Permanent Neutrality is a must-read for everyone interested in the rationales of the Holy See’s international engagement.

Notes:

[1] Ethiopian historians prefer to date the period from 1935 to 1941 because the fighting continued until the liberation of Addis Ababa by British and Ethiopian forces in May 1941, following six years of Italian occupation.

[2] See also Gerald J. Steinacher, “Forgive and Forget? The Vatican and the Escape of Nazi War Criminals from Justice” in S:I.M.O.N. – Shoah: Intervention. Methods. Documentation, 9 (2022) 1, 4-28.

[3] Peter C. Kent, The Lonely Cold War of Pope Pius XII: The Roman Catholic Church and the Division of Europe, 1943–1950. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002.

Christian internationalism has yet to find a secure place in the various histories of twentieth-century churches. Very largely this is due to a persistent emphasis on national categories and narratives, but denominational perspectives have also fashioned a great deal of what we expect to find in the foreground. All too often, Bell and Oldham may be observed, usually dutifully and briefly, hovering in the background of anything other than ecumenical surveys. In the final volume of the recent Oxford History of Anglicanism (OUP, 2019), Bell flits about here and there, but there is no very confident sense of where to put him for very long. Meanwhile, Oldham, the United Free Church layman, has almost vanished from ecclesiastical memory altogether. This is an authentic tragedy because it indicates how horizons have contracted across the western Protestant churches in the half-century since their deaths.

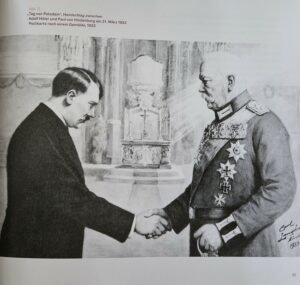

Christian internationalism has yet to find a secure place in the various histories of twentieth-century churches. Very largely this is due to a persistent emphasis on national categories and narratives, but denominational perspectives have also fashioned a great deal of what we expect to find in the foreground. All too often, Bell and Oldham may be observed, usually dutifully and briefly, hovering in the background of anything other than ecumenical surveys. In the final volume of the recent Oxford History of Anglicanism (OUP, 2019), Bell flits about here and there, but there is no very confident sense of where to put him for very long. Meanwhile, Oldham, the United Free Church layman, has almost vanished from ecclesiastical memory altogether. This is an authentic tragedy because it indicates how horizons have contracted across the western Protestant churches in the half-century since their deaths. After setting his agenda in the introductory chapter, Skiles outlines in Chapter 2 the religious conflicts under National Socialism, and more specifically, the division in German Protestantism between the German Christian movement, which sought to align Protestant theology and praxis with Nazi ideology, and the Confessing Church. For Skiles, at the foundation of that conflict was “a profound disagreement about the nature of divine revelation,” (p. 28) with the German Christians claiming to find divine revelation in history, national identity, and racial “science.” By contrast, the Confessing Church, in the spirit of the Reformation, held to the doctrine that knowledge of God is to be found in scripture alone. This chapter provides important context as it guides the reader through some of the early milestones in the regime’s conflict with the Confessing Church: the controversy over the “Aryan Paragraph” of 1933, which excluded clergy of alleged Jewish heritage from the pastorate; the subsequent formation of the Pastors’ Emergency League, which formed the basis for the Confessing Church; and the issuing of the Barmen Declaration in 1934. Skiles also effectively challenges in this chapter two common and simplified interpretations: that the Confessing Church was an anti-Nazi resistance group, and that the Confessing Church’s conflict with the regime was essentially about ecclesiastical freedom.

After setting his agenda in the introductory chapter, Skiles outlines in Chapter 2 the religious conflicts under National Socialism, and more specifically, the division in German Protestantism between the German Christian movement, which sought to align Protestant theology and praxis with Nazi ideology, and the Confessing Church. For Skiles, at the foundation of that conflict was “a profound disagreement about the nature of divine revelation,” (p. 28) with the German Christians claiming to find divine revelation in history, national identity, and racial “science.” By contrast, the Confessing Church, in the spirit of the Reformation, held to the doctrine that knowledge of God is to be found in scripture alone. This chapter provides important context as it guides the reader through some of the early milestones in the regime’s conflict with the Confessing Church: the controversy over the “Aryan Paragraph” of 1933, which excluded clergy of alleged Jewish heritage from the pastorate; the subsequent formation of the Pastors’ Emergency League, which formed the basis for the Confessing Church; and the issuing of the Barmen Declaration in 1934. Skiles also effectively challenges in this chapter two common and simplified interpretations: that the Confessing Church was an anti-Nazi resistance group, and that the Confessing Church’s conflict with the regime was essentially about ecclesiastical freedom. Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism.

Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism. Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less.

Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less. The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

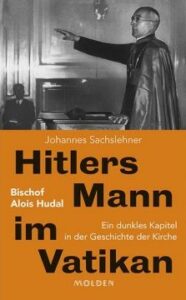

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position.

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position. Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true.

Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true. Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background.

Brenner first focuses on the background of the revolutionaries and their relationship to Judaism – a relationship that spanned a broad spectrum. The most influential was Kurt Eisner, who, on November 8, 1918, became minister-president of the Free State of Bavaria. Historian Sterling Fishman, whom Brenner quotes, described “the full-bearded” Eisner as speaking “like a Prussian,” sound[ing] like a socialist, and look[ing] like a Jew” (31). Eisner’s Judaism was not of particular importance to him but, at the same time, he did not bear any “feelings of hatred for his Jewish background” (32). Nevertheless, Jewish spirituality influenced Eisner through the mentorship of the Jewish scholar Hermann Cohen, whose writings emphasized a messianic theology, yearning for earth’s renewal and a heralding of God’s kingdom. The legislation he promoted, such as eight-hour workdays and women’s suffrage, concretized this spiritual hope. Eisner was unsuccessful in translating his ideas into reality and ultimately failed to win the support of the Bavarian population. For example, only one percent of Bavarian women voted for Eisner’s Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (42). His term was brief, ending on February 21, 1919, with a bullet from the gun of Count Anton von Arco auf Valley, a rejected applicant to the antisemitic Thule Society. Though many antisemites praised the assassination, Count Arco’s act failed to gain him admittance to the Society due to his mother’s Jewish background. Helge-Fabien Hertz’s weighty dissertation (2021) from Kiel University, supervised by Rainer Hering (Schleswig- Holstein State Archives), Peter Graeff and Manfred Hanisch (both from Kiel University), now joins this recent research tradition. The study consists of a group biography of the 729 pastors who worked in the Schleswig-Holstein state church shortly before and during the Nazi era (1930-1945). The study is based on a broad range of sources: the clergymen’s personal files were evaluated; in addition, the author has consulted sermons and confirmation lesson plans, denazification files, the relevant state church archive files on the Kirchenkampf, documents on NSDAP membership in the Berlin Federal Archives, and a wealth of contemporary lectures, articles, letters, diaries. Hertz uses a sophisticated set of social-science methods to operationalize the exorbitant amount of data from this large group of people (quantification of “attitudes” and “actions” with the aid of indicators) and to present it using a variety of statistics, diagrams, etc. One must admit at the outset, it is not always easy to keep track of the whole given the extreme complexity of the work’s organization into “parts”, “sections”, “chapters”, and so on.

Helge-Fabien Hertz’s weighty dissertation (2021) from Kiel University, supervised by Rainer Hering (Schleswig- Holstein State Archives), Peter Graeff and Manfred Hanisch (both from Kiel University), now joins this recent research tradition. The study consists of a group biography of the 729 pastors who worked in the Schleswig-Holstein state church shortly before and during the Nazi era (1930-1945). The study is based on a broad range of sources: the clergymen’s personal files were evaluated; in addition, the author has consulted sermons and confirmation lesson plans, denazification files, the relevant state church archive files on the Kirchenkampf, documents on NSDAP membership in the Berlin Federal Archives, and a wealth of contemporary lectures, articles, letters, diaries. Hertz uses a sophisticated set of social-science methods to operationalize the exorbitant amount of data from this large group of people (quantification of “attitudes” and “actions” with the aid of indicators) and to present it using a variety of statistics, diagrams, etc. One must admit at the outset, it is not always easy to keep track of the whole given the extreme complexity of the work’s organization into “parts”, “sections”, “chapters”, and so on. Bergen first asks what chaplains knew about the annihilation of the Jews and whether or not they sought to intervene. Working with letters individual chaplains sent to their bishops, friends, and family, official Wehrmacht reports on the chaplaincy, and more, Bergen paints an expected but devastating picture. Bergen demonstrates that the chaplains she studied were committed to their pastoral duties as they understood them. The chaplains celebrated religious services, counseled individual soldiers, and accompanied soldiers sentenced to death by a German court-martial on their final way. Before the war, Bergen shows, the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front. As Lauren Faulkner Rossi showed in her work Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation, the chaplains were constantly fighting efforts by the national socialist regime to curtail their activities, including the wartime decision not to replace chaplains killed or wounded in action with other chaplains and appoint Nationalsozialistische Führungsoffiziere (NSFO), national socialist leadership officers, instead. (Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015)). Beyond the fear of the NSFO, Bergen shows the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front.

Bergen first asks what chaplains knew about the annihilation of the Jews and whether or not they sought to intervene. Working with letters individual chaplains sent to their bishops, friends, and family, official Wehrmacht reports on the chaplaincy, and more, Bergen paints an expected but devastating picture. Bergen demonstrates that the chaplains she studied were committed to their pastoral duties as they understood them. The chaplains celebrated religious services, counseled individual soldiers, and accompanied soldiers sentenced to death by a German court-martial on their final way. Before the war, Bergen shows, the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front. As Lauren Faulkner Rossi showed in her work Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation, the chaplains were constantly fighting efforts by the national socialist regime to curtail their activities, including the wartime decision not to replace chaplains killed or wounded in action with other chaplains and appoint Nationalsozialistische Führungsoffiziere (NSFO), national socialist leadership officers, instead. (Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the War of Annihilation (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015)). Beyond the fear of the NSFO, Bergen shows the chaplains continuously sought to prove their relevance to the soldiers in the field, both to prove their Germanic manliness and to prove themselves worthy of serving at the front. The main source material that Madigan draws upon comes from the pontificate of Pius XI (1922-1939), the records of which only became available in 2006. But the story begins in the Risorgimento in the mid-nineteenth century and the triumph of a new liberal order that brought religious tolerance in the form of openness to non-Catholic religious confessions. Into this environment emerged evangelical Protestant missionaries from England and America, many of whom were Italian immigrants who had converted to a form of Protestantism in their new country and later returned to Italy. Methodists, Baptists, Pentecostals, the Salvation Army, the YMCA, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Adventists brought with them an evangelical style of preaching that emphasized conversion and an array of educational, medical, and social programs that benefited the Italian lower classes and peasantry. The fact that this Protestant missionary activity mapped onto a global trend of Protestant expansion in this period was all the more concerning for the Vatican, especially after World War I and the growth of Anglo-American power.

The main source material that Madigan draws upon comes from the pontificate of Pius XI (1922-1939), the records of which only became available in 2006. But the story begins in the Risorgimento in the mid-nineteenth century and the triumph of a new liberal order that brought religious tolerance in the form of openness to non-Catholic religious confessions. Into this environment emerged evangelical Protestant missionaries from England and America, many of whom were Italian immigrants who had converted to a form of Protestantism in their new country and later returned to Italy. Methodists, Baptists, Pentecostals, the Salvation Army, the YMCA, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Adventists brought with them an evangelical style of preaching that emphasized conversion and an array of educational, medical, and social programs that benefited the Italian lower classes and peasantry. The fact that this Protestant missionary activity mapped onto a global trend of Protestant expansion in this period was all the more concerning for the Vatican, especially after World War I and the growth of Anglo-American power. At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press.

At the outset, Chandler argues that British Christians and the Third Reich is an argument for the validity of a transnational approach to British history—one exploring not those networks rooted in the British Empire but rather those networks rooted in “that liberal moral consciousness which extended the boundaries of conventional politics in the age of mass democracy” (1). He aims to demonstrate “that the relationship between British Christianity and the Third Reich is indeed a solid subject and that it is one of significance” (2) to the ways we find patterns in and write about the past, and does so by means of a chronological study drawing on a rich array of sources, including correspondence, memoranda, published books, polemical pamphlets, British parliamentary debates, records of various church assemblies, and the vast output of both church and secular press. In 2015, a movement arose to repeal Gröber’s honorary town citizenship based on impressions contemporaries had of his speeches and his supposed support for the National Socialist regime, especially in 1933-34. In response, Mühleisen offers a differentiated analysis of Gröber and avoids definite judgment where ambiguity remains. Mühleisen also avoids moral judgment, which he argues is not the purpose of this historical study. He questions whether or not one can weigh moral accomplishments against moral failings to arrive at a “bottom line” judgment. In a fairly balanced account, Mühleisen discusses several lapses in judgment by Gröber, such as his decision to join the SS “booster club.” Also, Mühleisen notes that Gröber’s early public support for the regime confused the laity. While incomprehensible today, some have described membership in this organization as a protection racket. Similarly, in the first months of the new regime, Gröber emphasized his willingness to work with the new government authorities. Possible evidence for this is the Gestapo’s fear of Gröber’s fundamental opposition to the regime.

In 2015, a movement arose to repeal Gröber’s honorary town citizenship based on impressions contemporaries had of his speeches and his supposed support for the National Socialist regime, especially in 1933-34. In response, Mühleisen offers a differentiated analysis of Gröber and avoids definite judgment where ambiguity remains. Mühleisen also avoids moral judgment, which he argues is not the purpose of this historical study. He questions whether or not one can weigh moral accomplishments against moral failings to arrive at a “bottom line” judgment. In a fairly balanced account, Mühleisen discusses several lapses in judgment by Gröber, such as his decision to join the SS “booster club.” Also, Mühleisen notes that Gröber’s early public support for the regime confused the laity. While incomprehensible today, some have described membership in this organization as a protection racket. Similarly, in the first months of the new regime, Gröber emphasized his willingness to work with the new government authorities. Possible evidence for this is the Gestapo’s fear of Gröber’s fundamental opposition to the regime. In the volume under review, the contributions of different generations of historians reflect this evolution. The subject is Cardinal Lorenz Jaeger, Archbishop of Paderborn, 1941-1973. Before becoming archbishop, Jaeger had served as a regular army officer in World War One, then entered the seminary. He served as Dortmund’s youth pastor and teacher during the inter-war period. Upon the outbreak of World War II, Jaeger immediately volunteered as a military chaplain. Both in his capacity as a teacher and as a military chaplain, he had to pass background checks by Nazi authorities. Various contributors, however, note that, during Jaeger’s episcopal ordination process, the regime’s security authorities reported fundamental misgivings about his appointment. As early as 1935, authorities noted his rejection of Alfred Rosenberg’s Mythos des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. The Sicherheitsdienst [SD] and regional NSDAP offices considered him a threat to the regime. At the ministerial level, both sides tried to de-escalate conflicts in the broader context of the regime’s relations with the Catholic Church, especially in episcopal ordinations. So the Reich Minister of Church Affairs, Hans Kerrl, approved Jaeger’s ordination as Archbishop of Paderborn.

In the volume under review, the contributions of different generations of historians reflect this evolution. The subject is Cardinal Lorenz Jaeger, Archbishop of Paderborn, 1941-1973. Before becoming archbishop, Jaeger had served as a regular army officer in World War One, then entered the seminary. He served as Dortmund’s youth pastor and teacher during the inter-war period. Upon the outbreak of World War II, Jaeger immediately volunteered as a military chaplain. Both in his capacity as a teacher and as a military chaplain, he had to pass background checks by Nazi authorities. Various contributors, however, note that, during Jaeger’s episcopal ordination process, the regime’s security authorities reported fundamental misgivings about his appointment. As early as 1935, authorities noted his rejection of Alfred Rosenberg’s Mythos des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts. The Sicherheitsdienst [SD] and regional NSDAP offices considered him a threat to the regime. At the ministerial level, both sides tried to de-escalate conflicts in the broader context of the regime’s relations with the Catholic Church, especially in episcopal ordinations. So the Reich Minister of Church Affairs, Hans Kerrl, approved Jaeger’s ordination as Archbishop of Paderborn.