Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 2 (June 2021)

Conference Report: Martin Niemöller und seine internationale Rezeption – Martin Niemöller and his international reception, Frankfurt/Main, Germany, April 27-28, 2021

By Michael Heymel, Independent Scholar and Central Archives of the Protestant Church in Hessen and Nassau (retired)

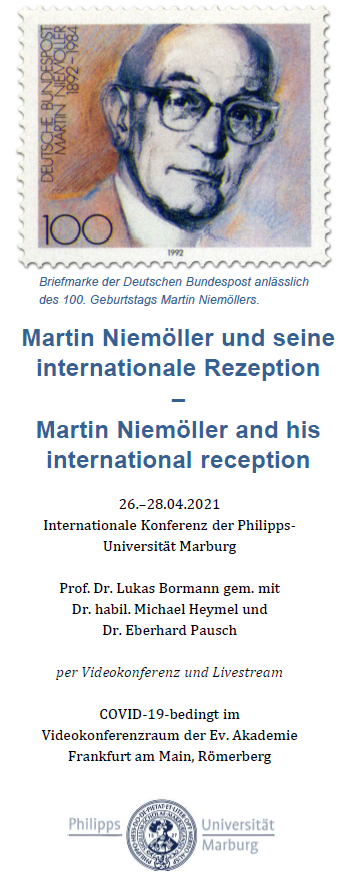

On this topic an international conference took place on April 27-28, 2021, at the Evangelische Akademie Frankfurt. The conference was conceived by Lukas Bormann, professor for New Testament research at Philipps-Universität Marburg, together with practical theologian Michael Heymel, and was conducted in collaboration with study director Eberhard Pausch. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was held as a videoconference.

Martin Niemöller (1892-1984) is one of the most internationally known German Protestant church leaders and theologians of the 20th century. For some years he has been back in the discussion through the biographies of Heymel (2017), Hockenos (2018), Ziemann (2019) and Rognon (2020). Historian Benjamin Ziemann takes a particular position. He emphasizes Niemöller’s temporary closeness to German national (völkische) movements and problematizes his attitude toward Judaism and Jewish people, the attribution of his activities from 1933 on as resistance against the Nazi regime, his criticism of the Lutheran regional churches, and his contribution to the ecclesiastical discourse on guilt to 1948.

Martin Niemöller (1892-1984) is one of the most internationally known German Protestant church leaders and theologians of the 20th century. For some years he has been back in the discussion through the biographies of Heymel (2017), Hockenos (2018), Ziemann (2019) and Rognon (2020). Historian Benjamin Ziemann takes a particular position. He emphasizes Niemöller’s temporary closeness to German national (völkische) movements and problematizes his attitude toward Judaism and Jewish people, the attribution of his activities from 1933 on as resistance against the Nazi regime, his criticism of the Lutheran regional churches, and his contribution to the ecclesiastical discourse on guilt to 1948.

The conference, supported by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation for the Promotion of Science and the EKHN Foundation, took up these topics in the new Niemöller debate. It presented contributions on basic questions of Niemöller research and on the reception of Martin Niemöller in five European countries and the USA, which were discussed in an interdisciplinary and multinational exchange. This was done in order to arrive at a historically and theologically reflected re-evaluation of Niemöller’s work in international perspective.

Section I dealt with the particularly controversial topics of anti-Semitism and resistance. Benjamin Ziemann (Sheffield) emphasized Niemöller’s racial antisemitism as seen in his connection to the Deutsch–Völkischer Schutz- und Trutzbund after the First World War. This völkisch antisemitism remained in place through the balance of the Weimar era. Beginning in 1931-1932, Niemöller embarked on a theological interpretation of Jewry and Judaism but continued to struggle with antisemitism even into the postwar era.*

When asked if Niemöller had been a man of resistance against the Nazi regime, Victoria Barnett (Washington) answered with a “cautious no.” She indicated that resistance was a complicated matter. Personality and a common language played an important role. As a “good German,” Niemöller had seen himself in opposition to the ‘German Christians’ (Deutsche Christen), similar to other nationalist Germans. Others, especially women, had been clearer in their opposition. The Nazi policy against the church had touched him as a pastor and in his loyalty to the fatherland and challenged him as a fighter, which he had been by nature. He had been seen as a successor to Luther who became a preacher of resistance. With regard to Niemöller’s conflict between nationalistic loyalty and Nazi church policy, Barnett brought his attitude to the concept of a “loyal resister”.

Malte Dücker (Frankfurt) suggested that Niemöller should be viewed from the perspective of cultural studies as a figure of memory. He distinguished phases of reception, which were characterized by companions of the Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche, or BK), church-historical heroization, and the deconstruction of Niemöller legends in response to them. Niemöller was portrayed as a Christian who confronted the rulers like Luther in Worms, or as a socio-political Protestant who appeared like a biblical prophet (i.e. Jeremiah). He was perceived as an authentic personality. In contrast, narrative contextualization of today’s post-heroic society shows him as an ambivalent hero with fractures and contradictions. An artistic form (musical, drama, film) could be suitable for this.

The lectures in Section II were devoted to Niemöller’s reception in European Protestantism and dealt especially with the period after 1945. Frédéric Rognon (Strasbourg), who presented the first French biography on Niemöller in 2020, made clear that his name is generally unknown in France today. Before 2020, only one book about him and one by him had been published: in 1938 an anonymous, hagiographically colored writing about the everyday life of the Dahlem pastor, in 1946 a brochure with four texts about German guilt, which hardly allowed French readers to understand Niemöller’s special situation. To this day, he is not recognized in France because he was German and a pastor, and especially in secular France there is a strong distrust of religious people. Moreover, for the Protestant minority, he is overshadowed by Bonhoeffer. But it is precisely the paradoxical character of his life and thought that encourages people to identify with Niemöller.

Stephen Plant (Cambridge) outlined how the relationship between Niemöller and Karl Barth changed from casual allies in the 1930s to respectful friends after 1945. For both, he said, the Lutheran churches offered a common front. Barth had seen in Niemöller “too good a German” and “too good a Lutheran.” After the end of the war, he honored him as a symbol of resistance and reaffirmed his full confidence in Niemöller when it came to the future path of the church in Germany and a confession of guilt. He also noted Niemöller’s “blind spot for church diplomacy” and admonished him in 1951 to concentrate his energies. The confessional synod in Barmen (1934) had made Barth and Niemöller colleagues, the church conference in Treysa (1945) friends.

Wilken Veen (Amsterdam) spoke about the reception of Niemöller’s appearances and speeches in the Netherlands. There he is one of the ten best-known Germans. Niemöller was very popular as a resistance fighter after 1945; he was identified with the Confessing Church and was acclaimed like a movie star during his first visit in 1946. Franz Hildebrandt’s anonymous writing of 1938 had been translated immediately. Although a nationalist, Niemöller had preached biblical sermons. His sermons in the Netherlands had been evangelistic and missionary, and only in his speeches had he expressed himself politically.

Peter Morée (Prague) illuminated Niemöller’s relationship with Josef L. Hromádka against the backdrop of the special situation of the Czech Protestant Church as a minority church in an Eastern Bloc state. Church and state were ecumenically isolated here after 1945. Hromádka had contacts with Karl Barth and the Confessing Church. Without him there would have been no ecumenical relations. Niemöller came to Prague in 1954; his visit had been in the interest of the Politburo of the Communist Party since 1951. He and Hromádka would have known that their friendship was determined by the political agenda. The Christian Peace Conference (CFK) had been founded in 1958 together with representatives of the BK (including Iwand, Vogel and Gollwitzer) in response to the refusal of the World Council of Churches (WCC) to cooperate with the World Peace Council (WFR), which had existed since 1950.

Section III focused on Niemöller as a preacher and theologian. Alf Christophersen (Wuppertal) problematized Niemöller’s position between Lutheranism and Catholicism. In his notes of 1939, there was only one church for Niemöller; his exclusive model only allowed being Catholic or Protestant. From his point of view, Luther’s mistake had been that there was no longer any magisterial authority; the confessional writings could not be updated. Niemöller had formed an ideal image of Catholicism. Later, he did not see a plural Protestantism, but polarized it through his declamatory preaching.

Michael Heymel (Limburg/Lahn) presented Niemöller in three ecclesiastical fields of work—as preacher, theologian, and ecumenist. Niemöller’s sermons from 1945 to 1981, unlike those of the Dahlem period, have not yet been critically edited, and comparative studies are lacking. Niemöller had always wanted to preach Jesus Christ as the only Lord and to reach people in the reality of their lives. As a Bible-oriented theologian, influenced by Luther and Prussian Pietism, and one who was concerned with faith and the church as a Christocratic brotherhood, he criticized an academic theology without reference to the congregation. As an ecumenist, he said, he worked for communion with Christ in all churches and the “brotherhood of all people” and adhered to the WCC’s programmatic objectives. “The time of the white man is over,” he declared, adding that one must adjust to an ecumenism not dominated by the West.

Lukas Bormann (Marburg) devoted himself to Niemöller’s approach to the Bible in the Dahlem sermons, first emphasizing the importance of scriptural interpretation in the sermon and the service in a cognitive science perspective as a religious ritual. As a preacher in 1933-1937, Niemöller stood in a unique way for the religious distinctiveness of Protestantism. In his sermons on Volkstrauertag, or Heldengedenktag from 1934 on, there was no enthusiasm for war and no heroic pathos, but rather an increasing distancing from the National Socialist instrumentalization of “heroic remembrance.” The preacher addressed a “we” beyond the National Socialist state, created solidarity among those who positioned themselves beyond National Socialism, and strengthened the individual. Admittedly, an ethical orientation in the sense of a ‘church for others’ (Kirche für andere) was missing.

Matthias Ehmann (Ewersbach) pointed to a forward-looking theological contribution of Niemöller to the transnational responsibility of the churches. At the WCC World Conference on Migration in June 1961, Niemöller, at the beginning of his term as one of the presidents of the WCC, called on the churches to show solidarity with non-Christian migrants. He referred to the image of the Good Samaritan and stressed that mission to people in need took precedence over church structures. An increase in churches founded by migrants was to be expected, he said. Ehmann praised Niemöller’s speech as a differentiated contribution to interreligious dialogue that took into account the growing diversity of the churches.

Section IV turned to the leading figure of the Pfarrernotbund and later church president. Thomas Martin Schneider (Koblenz-Landau) characterized the Barmen Theological Declaration (BTD) as a church-political and theological consensus paper and confession of basic Reformation truths, which was received differently in the two wings of the Confessing Church. The BTD did not contain a political program, but after 1945 it was claimed politically for different goals. It had been called the “sum” of Niemöller’s theology, although as late as 1934 he referred to theological teachers such as Wehrung and Althaus who were in tension with the BTD. He was concerned with the one ecclesiastical office of preaching, whereas the fourth Barmen thesis speaks of ministries of equal rank. Niemöller had no understanding for Lutheran concerns—the experience of Barmen was more important to him than the theology of the BTD. All in all, he only took up the Christocentrism of the first thesis, but showed hardly any interest in the other theses.

Gisa Bauer (Karlsruhe) looked at the relationship between Niemöller and the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau (EKHN) from the perspective of the history of perception. In the official self-representation of the EKHN, Niemöller stood for a political church. The radical wing of the EKHN had voted for him as church president. Pastors of this direction had been strongly positioned in Hesse; the regional council of brethren had elected him as chairman in 1946. Niemöller helped to shape the first thrusts of the politicization of the EKHN, after which he became its symbol. The commemorative publication of 1982 and funeral and memorial speeches of 1984 elevated him to the pantheon of the political church. It is difficult to separate the symbolic and the historical person, Bauer pointed out.

Jolanda Gräßel-Farnbauer (Marburg) showed how Niemöller positioned himself in the process towards equality for women in church positions. While he was initially ambiguous in the church synod and in 1955 still argued from the basis of creation-related biological differences between men and women, in 1958-1959 he argued for a law on women pastors, which paved the way for equality. In 1969, he even proposed Marianne Queckbörner, then only 37 years old, to the synod as church president, but Helmut Hild was elected. The EKHN still does not have a woman as church president at its head. How it would have developed if Niemöller’s suggestion had been followed stimulates the historical imagination considerably. Niemöller had taken a positive attitude towards women vicars in the church struggle. He did not share the anti-feminism of some representatives of the Confessing Church, who denied women the administration of the sacraments.

Finally, Section V focused on Barmen and the legacy of the Confessing Church, with two lectures examining Niemöller in the light of his relationship with two fellow Confessing Church members in the postwar period. Gerard C. den Hertog (Amsterdam) spoke about Niemöller’s and Hans Joachim Iwand’s common path from national Protestantism to the ecumenical peace movement. Iwand came from eastern Germany, was a soldier and became involved in the Freikorps in 1921. As a theologian, he presented a polemical Luther. Niemöller had known Iwand since September 1934 and had received his Luther studies, which advocated the doctrine of justification, in the concentration camp. As a Dortmund pastor, Iwand was committed to Jews; there was no anti-Semitism in him. Niemöller had been “the closest of friends” with him and had written to him: “We understand each other before we talk to each other.”

On the other hand, Hannah M. Kreß (Münster) made clear how the relationship between Niemöller and Hans Asmussen changed between 1945 and 1948. The latter had been involved in the Reich Church since 1933, was active at the Church College in Berlin and supported Else Niemöller during her husband’s imprisonment. Conflicts broke out in Treysa, where Asmussen became the head of the Evangelische Kirche Deutschlands (EKD) church chancellery. He was concerned that the brethren councils might gain too much influence among the Lutherans. In a letter to him in 1946, Niemöller had reckoned with the founding of the EKD. It lacked the connection to Barmen. He feared an understanding of ministry in the EKD that he considered to be hierarchical in the style of Catholicism. Asmussen had come into conflict with the Council of the EKD and left office in 1948. In that year, Niemöller had broken off his friendship with him. An important role in the alienation process was played by the disagreement over the church’s participation in public political activities.

Arno Helwig (Berlin) reported on remembrance work at the Martin Niemöller House in Berlin-Dahlem, which served as a peace center in the intellectual environment of Gollwitzer and Marquardt from 1980 to 2007 and was shaped as such by Pastor Claus-Dieter Schulze. After 2007, it became a memory and learning space. The former pastor in Dahlem, Marion Gardei, is now the commissioner for remembrance culture in the Evangelische Kirche Berlin-Brandenburg-schlesische Oberlausitz (EKBO). In 2018-2019, the house was reopened with a permanent exhibition covering the topics of Jews, human rights, social responsibility and resistance to the Nazi dictatorship. Niemöller’s work after 1945, however, is almost completely missing.

What remains of the Confessing Church? Who carries on the memory of it? Harry Oelke (Munich) took up these questions about the significance of the legacy of Barmen for today’s Protestantism, limiting himself to the German Protestantism of the regional churches. Four phases of the culture of remembrance of the Confessing Church can be distinguished: (1) a contemporary witness-supported communicative memory formation (1945-1970), in which church history was written by and about participants and, with the exception of Niemöller’s call to repentance, no self-critical remembrance was practiced (“Confessing Church myth”); (2) a politicization, polarization, and pluralization of Christian value concepts (1970-1989); (3) a canonization (1990-2005), in which the Confessing Church had become a part of Protestant identity. (4) The present perspectives (since 2005) have been characterized by the loss of contemporary witnesses, the end of the culture of excitement, an objectification of the culture of historical scholarship and, in some tension with this, a tendency towards moral evaluation.

The final discussion circled around open questions and tasks of further research. 75 years after the end of the war, there is a danger that the Protestant Church will shirk its responsibility for the legacy of the Confessing Church, especially since the EKD is planning a considerable reduction in funding for the Institute for Contemporary Church History. Who would be the bearer of the memory of the Confessing Church in the future was up in the air. Benjamin Ziemann made it clear that he was against renaming institutions that bear Niemöller’s name. It remains to be considered how Niemöller could be present in a contemporary form in the practical culture of remembrance. Dahlem, with its new exhibition, stands as an example of how the memory of Niemöller is possible in a post-migrant society.

Research will focus on clarifying open questions about Niemöller’s understanding of preaching after 1945, his ecumenical commitment against colonialism and racism, and his attitude toward the state of Israel. For this purpose, further sources have to be opened up for scholarship, such as Niemöller’s unedited sermons after 1945, the sources on his activities as president of the World Council of Churches or also as head of the administrative council of the Palestine Association. Terms such as ‘anti-Semitism’ and ‘resistance’ need to be further differentiated and clarified in relation to Niemöller. When it comes to the Confessing Church, the concept of resistance should in any case not be too narrowly defined. Finally, theological and non-theological perspectives of the perception of the life and work of Martin Niemöller must be combined.

A conference volume is to be published in the series “Arbeiten zur kirchlichen Zeitgeschichte” (AKIZ.B) by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen.

* This paragraph was edited for clarity after publication.

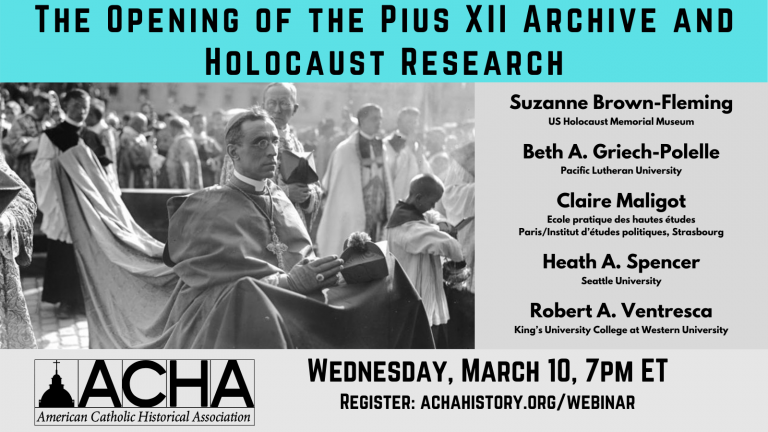

On March 10, 2021, the American Catholic Historical Association held a webinar entitled “The Opening of the Pius XI Archive and Holocaust Research.” Presenters included Suzanne Brown-Fleming, US Holocaust Memorial Museum: Beth A. Griech-Polelle, Pacific Lutheran University; Claire Maligot, Ecole pratique des hautes études, Paris, and Institut d’études politiques, Strasbourg; Heath A. Spencer, Seattle University; and Robert A. Ventresca, King’s University College at Western University.

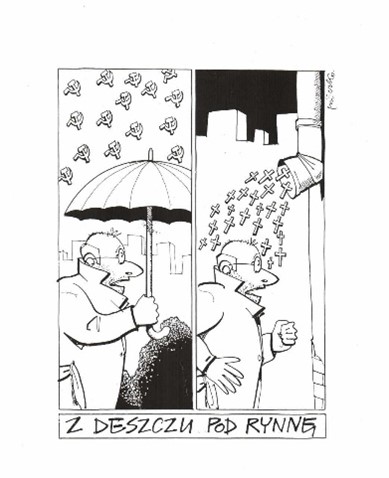

On March 10, 2021, the American Catholic Historical Association held a webinar entitled “The Opening of the Pius XI Archive and Holocaust Research.” Presenters included Suzanne Brown-Fleming, US Holocaust Memorial Museum: Beth A. Griech-Polelle, Pacific Lutheran University; Claire Maligot, Ecole pratique des hautes études, Paris, and Institut d’études politiques, Strasbourg; Heath A. Spencer, Seattle University; and Robert A. Ventresca, King’s University College at Western University. Because of the relevance of this topic—and propelled by the insurrectionist violence we witnessed at the U.S. Capitol on January 6—the Martin-Springer Institute* put together a 4-part Zoom conversation series on Christian nationalism in April 2021. Titled Unholy Alliance: Nationalism and Christianity, the series took a comparative approach by bringing in voices from different national contexts: Victoria Barnett on “Protestants and Ethno-Nationalism in Nazi Germany”; Sarah Posner on “The Rise of Christian Nationalism Among American White Evangelicals”; Annamaria Orla-Bukowska on “Roman Catholicism, the Church, and Polishness in Contemporary Poland”; and Katya Tolstaya on “Post-Soviet Patriotism, Nationalism, and Russian Orthodoxy.”

Because of the relevance of this topic—and propelled by the insurrectionist violence we witnessed at the U.S. Capitol on January 6—the Martin-Springer Institute* put together a 4-part Zoom conversation series on Christian nationalism in April 2021. Titled Unholy Alliance: Nationalism and Christianity, the series took a comparative approach by bringing in voices from different national contexts: Victoria Barnett on “Protestants and Ethno-Nationalism in Nazi Germany”; Sarah Posner on “The Rise of Christian Nationalism Among American White Evangelicals”; Annamaria Orla-Bukowska on “Roman Catholicism, the Church, and Polishness in Contemporary Poland”; and Katya Tolstaya on “Post-Soviet Patriotism, Nationalism, and Russian Orthodoxy.”

Martin Niemöller (1892-1984) is one of the most internationally known German Protestant church leaders and theologians of the 20th century. For some years he has been back in the discussion through the biographies of Heymel (2017), Hockenos (2018), Ziemann (2019) and Rognon (2020). Historian Benjamin Ziemann takes a particular position. He emphasizes Niemöller’s temporary closeness to German national (völkische) movements and problematizes his attitude toward Judaism and Jewish people, the attribution of his activities from 1933 on as resistance against the Nazi regime, his criticism of the Lutheran regional churches, and his contribution to the ecclesiastical discourse on guilt to 1948.

Martin Niemöller (1892-1984) is one of the most internationally known German Protestant church leaders and theologians of the 20th century. For some years he has been back in the discussion through the biographies of Heymel (2017), Hockenos (2018), Ziemann (2019) and Rognon (2020). Historian Benjamin Ziemann takes a particular position. He emphasizes Niemöller’s temporary closeness to German national (völkische) movements and problematizes his attitude toward Judaism and Jewish people, the attribution of his activities from 1933 on as resistance against the Nazi regime, his criticism of the Lutheran regional churches, and his contribution to the ecclesiastical discourse on guilt to 1948.