Webinar Note: Christian Nationalism – A Conversation

Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 2 (June 2021)

Webinar Note: Christian Nationalism – A Conversation

By Björn Krondorfer, Northern Arizona University

At the time of this writing, the 2021 Southern Baptist Convention in Nashville is battling for its soul: Should they adhere to their conservative interpretations of biblical values to fight back against the perceived evils of secular modernity? Or should they confirm a politicized evangelicalism that is deeply rooted in southern white culture and epitomized by a categorical support of Trumpism? Put differently, will southern Baptists continue to battle their century-old “culture wars” for the sake of individual salvation, or define themselves as fighting a “political war” for the soul of the nation?

While, for decades, scholars and observers have read the anti-modernist, anti-humanist, and scripturalist impulse of American Christianity as an expression of religious fundamentalism, the analytical (and popular) literature has recently shifted its discourse to speak about Christian nationalism: the idea that it is more important to defend a particular—and, no doubt, mythologized—version of America as a divinely-ordained nation than limiting one’s mission to the preaching of a biblical-ordained lifestyle. As Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry put it in their study, Taking America Back For God: Christian Nationalism in the United States (2020), “The ‘Christianity’ of Christian nationalism represents something more than religion, [such as] assumptions about nativism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and heteronormativity, along with divine sanction for authoritarian control and militarism.”

Because of the relevance of this topic—and propelled by the insurrectionist violence we witnessed at the U.S. Capitol on January 6—the Martin-Springer Institute* put together a 4-part Zoom conversation series on Christian nationalism in April 2021. Titled Unholy Alliance: Nationalism and Christianity, the series took a comparative approach by bringing in voices from different national contexts: Victoria Barnett on “Protestants and Ethno-Nationalism in Nazi Germany”; Sarah Posner on “The Rise of Christian Nationalism Among American White Evangelicals”; Annamaria Orla-Bukowska on “Roman Catholicism, the Church, and Polishness in Contemporary Poland”; and Katya Tolstaya on “Post-Soviet Patriotism, Nationalism, and Russian Orthodoxy.”

Because of the relevance of this topic—and propelled by the insurrectionist violence we witnessed at the U.S. Capitol on January 6—the Martin-Springer Institute* put together a 4-part Zoom conversation series on Christian nationalism in April 2021. Titled Unholy Alliance: Nationalism and Christianity, the series took a comparative approach by bringing in voices from different national contexts: Victoria Barnett on “Protestants and Ethno-Nationalism in Nazi Germany”; Sarah Posner on “The Rise of Christian Nationalism Among American White Evangelicals”; Annamaria Orla-Bukowska on “Roman Catholicism, the Church, and Polishness in Contemporary Poland”; and Katya Tolstaya on “Post-Soviet Patriotism, Nationalism, and Russian Orthodoxy.”

Though the focus of the series was not to directly address the links between religiously inspired anti-democratic groups across different nations, it is important to note that such transatlantic networks exist between American ultra-conservative evangelicals and their Orthodox and Catholic counterparts in Eastern Europe. We could call this cooperation a new kind of ecumenical alliance that seeks common ground on anti-abortion, anti-LGTBQ, anti-woman health, and anti-democratic platforms; their leaders believe that strong, autocratically-ruled states will promote their religious values, such as in Putin’s Russia, Orban’s Hungary, and Poland’s Law and Justice party. In the U.S, the Institute for Cultural Conservatism or the World Congress of Families, founded and promoted by people like Paul Weyrich, William Lind, and Brian Brown, have embraced the authoritarian style of Putin and Orban as models for a renewed America.

Victoria Barnett, former director of the USHMM’s Program on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust, started the series with an analysis of the Protestant churches during the Third Reich, geared toward an audience of non-specialists. Given the historical proclivity of German Protestants to identify with a German nation-state, it was not surprising that many Germans—after the defeat in 1918 and the perceived national humiliation of the Versailles Treaty—had high hopes that Hitler would restore Germany to its rightful (and superior) place among nations. In 1933, when Hitler took power, there was little opposition by the churches, until the moment when some theologians and clergy began to fear the Nazi encroachment on church autonomy. Those familiar with this history would quickly recognize the distinctions Barnett drew between the three evolving movements: the Deutsche Christen (German Christians), the Confessing Church, and the patriotic middle (the so-called “intact churches”). The Deutsche Christen, Barnett explained, was a “Christian nationalist, pro-Nazi group within the German Protestant church.” Its “politically nationalistic, right-wing” supporters “developed an understanding of Protestantism that was strongly ethnicized.” They emphasized “the Germanic nature of their faith [and] affirmed much of the Nazi platform.” When asked about lessons learned for today, Barnett pointed to the failure of the church to find a strong oppositional voice to Nazism. She mentioned the tragedy of becoming bystanders—of what Bonhoeffer bemoaned as the “silent witnesses of evil deeds.” Her presentation can be viewed here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=msc6ZV4eT94&list=PLvTDA4SpA8Z408WLA4D68ZXlzrY3z5aM-

Our second speaker, Sarah Posner, author of Unholy Alliance: Why White Evangelicals Worship at the Altar of Donald Trump (2020), introduced our Zoom audience to the development of American fundamentalist evangelicals and their battles since the 1950s. She asked how a religious movement that presented itself originally as a defender of religion and family values turned into a political force. “The conceptualization of America as a Christian nation that is under threat by secularism,” she argued, “accelerated in the second half of the twentieth century.” She concluded by pointing out the danger of anti-democratic convictions among white evangelicals who deploy religion for their own political agendas. Given these developments, she cautioned that “complacency is not an option.” Her presentation can be viewed here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=vCUvl3EkoZU&list=PLvTDA4SpA8Z408WLA4D68ZXlzrY3z5aM-&index=2&t=3775s

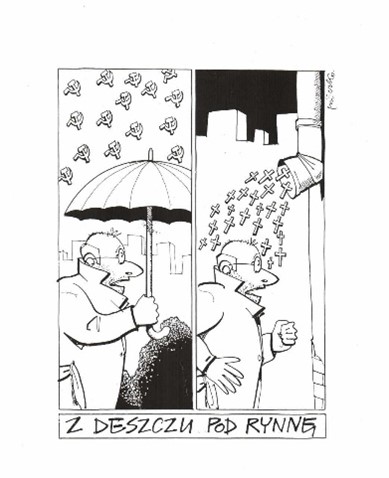

“Out of the frying pan into the fire” (literally, “from the rain into the eaves”), this cartoon critically depicts Poland’s transition from communist to Catholic (state) ideology.

Anna Maria Orla-Bukoswka from Jagiellonian University in Krakow introduced our audience to the contemporary landscape of Polish Catholicism, with its split between, what she called, the “open and closed” church. Whereas the former promotes openness to dialogue with civil society and embraces diversity (including Catholic-Jewish relations), the closed church refers to the clerical hierarchy working in tandem with nationalist themes promoted by the Law and Justice party. Referencing the “founding myth of Polish history as the Chrzest polski, the Baptism of Poland in 966,” she presented a more complex history of the slow Christianization of Poland with its multicultural and ethnically diverse population. Only as a result of the Holocaust and the redrawing of borders after 1945 did Poland become a majority Catholic population, though religion remained repressed under Communism. “The entire modern Polish history,” she argued, “has taught Poles not to trust the State but the Church.” As a result, Roman Catholicism and Polish nationalism became entangled entities, which led to the current marriage between church and state authorities pursuing an illiberal agenda and discriminating against minority groups. Her presentation can be viewed here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=21V-gVCRkyc&list=PLvTDA4SpA8Z408WLA4D68ZXlzrY3z5aM-&index=3&t=18s

Katya Tolstaya, Professor of Religion and Theology in Post-Trauma Society at the Vrije University of Amsterdam, introduced current themes of nationalism and Russian Orthodoxy in post-Soviet Russia. Briefly delineating some key differences between Orthodoxy and Catholicism and Protestantism (such as the central role of icons and martyrs), she traced the alliance of Russian patriotism and Orthodoxy to Dostoyevsky who had stated that “to be Russian is to be Orthodox”—a phrase, according to Tolstaya, that is often quoted by extreme Russian nationalists today. Despite religious and ethnic diversity in post-Soviet society, “Orthodoxy has become the national church in Russia.” Orthodoxy is not only a powerful force shaping society but is also deployed to legitimate national expansion into other regions today, such as Ukraine. Tolstaya lamented the lack of transparency regarding suspected collaboration between the KGB and the church in the Soviet Union, the lack of a “civil society” in Russia today, and the participation of theologians in “operationalizing sacred liturgical texts” for xenophobic and nationalist purposes. Her presentation can be viewed here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYrDTHP9NWk&list=PLvTDA4SpA8Z408WLA4D68ZXlzrY3z5aM-&index=4&t=25s

Though in no way exhaustive, this series brought attention to the fact that religion—which in the second half of the twentieth century was seen as a waning force—has resurfaced as a main player in society and politics, often supporting illiberal and nationalist visions of governance and policies.

* The Martin-Springer Institute attends to the experiences of the Holocaust in order to relate them to today’s concerns, crises, and conflicts. Our programs promote the values of moral courage, tolerance, empathy, reconciliation, and justice. Founded by Doris, who survived the Holocaust, and her husband Ralph Martin, the Institute fosters dialogue on local, national, and international levels. http://nau.edu/martin-springer