Association of Contemporary Church Historians

(Arbeitsgemeinschaft kirchlicher Zeitgeschichtler)

John S. Conway, Editor. University of British Columbia

November 2008— Vol. XIV, no. 11

Dear Friends,

This month marks the seventieth anniversary of the scandalous Nazi atrocity against the Jewish people, commonly known as the Crystal Night pogrom, during which the churches‚ failure to stand by the persecuted victims was notable, and is today seen as a symptom of their larger failure to oppose the whole Nazi system of ideological fanaticism and political oppression. But a few lone voices did protest. It is therefore perhaps fitting that this month’s reviews should be about the few courageous individuals who stood against the main stream, such as Elisabeth Schmitz, Eberhard Arnold and Pastor Paul Schneider.. Also that we should draw your attention to a new book about the striking movement in the German Evangelical Church after the war, which explicitly saw its Christian mission to bring reconciliation and repentance from Germany to the victims.

Contents:

1) Book reviews:

a) ed. M. Gailus, Elisabeth Schmitz

b) H. Brinkmann, God’s Ambassador. The Bruderhof in Nazi Germany

c) R. Wentorf, Paul Schneider

d) G. Kammerer, Aktion Sühnezeichen. Friedensdienst

2) Memorial Tribute to Bishop Bell by Bishop Huber of Berlin

3) Book notes,

a) Blues Music and the Gospel Proclamation

b) Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania

4) Journal issue: Religion, State and Society

1a) Ed. M .Gailus, Elisabeth Schmitz und ihre Denkschrift gegen die Judenverfolgung. Konturen einer vergessenen Biographie (1893-1977). Berlin: Wichern Verlag 2008 ISBN 978-3-88981-213-8. 230 Pp.

Heroines are seldom found in the story of the Protestant Church Struggle against National Socialism. Very probably, this is because the history was written entirely by men. But now, recognition is being given to one woman, Dr Elisabeth Schmitz, for a small but striking contribution, which was alas! ignored at the time and forgotten ever since. In 1935 she had the courage to challenge the members of her Confessing Church, led by such men as Martin Niemöller and Karl Barth, to face up the Nazis‚ increasingly violent persecution of Germany’s Jews. The Memorandum she produced for the 1935 Synod was a model of clarity and foresight, which accurately predicted the likely fate of the Jewish minority in Germany. At the same time, she called on the Church to stand by its responsibility to defend the most threatened members of society, and to protest against the criminal discrimination being practised by the Nazi government.

Such a stance was highly unpopular. Only a few colleagues in the Confessing Church shared Dr Schmitz’s views. The fact that the Memorandum was put forward by a lay woman, who held no office in the Church, cannot have enhanced her cause. It was a sign of how far Nazi propaganda had already affected church ministers that, even in 1935, the majority of the responsible pastors were averse to giving any support to Jews, or at least reluctant to show any hostility to the now increasingly popular Nazi government.

Who was Elisabeth Schmitz? These essays, written for a 2007 conference, (briefly described in a German report in our Newsletter for September 2007) provide a succinct account of her career as a school mistress, trained under such distinguished scholars as Adolf von Harnack and Friedrich Meinecke. Since women were not allowed to be ordained at that time in the Evangelical Church, she went on to teach both religion and history to senior girls in high school. Her disposition was reserved, conscientious and highly upright in the German Protestant tradition. When convinced of the correctness of her views, she could be inflexible and determined. She refused to allow her independence of mind to be compromised for the sake of personal or political advantage. With such high intellectual and moral standards, she was naturally appalled by the fanatical tone of the Nazis‚ anti-Semitic tirades, as displayed in the press, the radio and party rallies. These contradicted her sense of order, truthfulness and human compassion. These propaganda attacks and attendant violence were totally antithetical to the values she tried to teach her students. She was inspired to make her early protest particularly by the fact that a close friend of Jewish origins had been dismissed from her medical practice. Elisabeth Schmitz offered her help and hospitality, and was subsequently denounced to the Gestapo for sharing her living quarters with as member of the despised race. This accumulated poisonous atmosphere, culminating in the Crystal Night pogrom of November 1938, led to Elisabeth Schmitz’s determination to give up her teaching position, since she could no longer in conscience teach as the Nazis ordered. Fortunately she was allowed to take early retirement, and returned to teaching after the war was over.

At the time she prepared her Memorandum on behalf of the Jews in the summer of 1935, the situation of the Protestant churches, and the Confessing Church in particular, was acutely critical. The Nazis had just appointed a new Minister for Church Affairs, and threatened to seize control of church administrations. Invective and propaganda attacks against the churches, as agents of World Jewry, were increasingly common and virulent, especially in the pages of Der Stürmer, the radical newspaper distributed nation-wide by the Nazi party agencies.

Most of the conservative clergy, especially the church leaders, while deploring the extremism of Der Stürmer, sought to prove their national loyalty. None wanted an open conflict with the state, particularly not on such a unpopular and touchy subject as the treatment of the Jews. It was therefore hardly surprising that Elisabeth Schmitz’s Memorandum was not debated at the 1935 Synod meeting. Only a half-hearted resolution was passed, affirming the universal duty of the Church to offer baptism to all, regardless of race. By ignoring the wider issue of the human rights of the Jews in Germany, the Confessing Church was able to avoid the possibility of being suppressed by the Gestapo. It was a Pyrrhic victory.

Three years later, at the time of the November 1938 pogrom, Schmitz repeated her challenge. She wrote a strong letter to Pastor Helmut Gollwitzer, who was in charge of Berlin’s most prominent church in Dahlem, after the arrest and imprisonment of Pastor Martin Niemöller. In this letter she called for the mobilization of church opinion to protest against the wanton violence against the Jews, suggested that church space be made available for the orphaned or burnt-out Jewish congregations, and urged that monetary collections be taken up to alleviate Jewish suffering. None of this happened.

The text of Schmitz’s Memorandum is here printed in full, along with a postscript written some months later. Since most of the information came from the public press, it does not reveal anything new about the Nazis‚ anti-Semitic campaign. Rather, its value today consists in showing how much an engaged witness could know about the extent of the violence, hatred, intimidation and discrimination practised against the Jewish minority, and about the dire consequences being felt by these victims. It is imbued with a strong sense of indignation at the injustices being inflicted, and an equal sense of frustration that the churches failed to take timely action to put a spoke in the wheel of such outrageous activities.

This collection of essays, ably edited by Professor Manfred Gailus, is a heart-warming, if belated, tribute. But it hardly explains why Schmitz’s contribution was for so long forgotten, or even incorrectly attributed to others. Gailus suggests some of the relevant factors, but the mystery remains. It is possibly all part of that painful and reluctant process of coming to terms with the past on the part of the German Protestant Church. It is also part of the process of trying to forge a new and better relationship between the Church and the Jewish people. It is therefore good that we can now hear the pioneering but lonely voice of this courageous lay woman, Elisabeth Schmitz.

It is equally welcome news that an American filmmaker, Steven Martin, has now compiled a documentary DVD film, entitled Elisabeth of Berlin, which will shortly become available for distribution. This 60-minute English-language documentary, fills in the background of Schmitz‚ protests. Archival footage of the Crystal Night is linked to the feelings of outrage shared by such people as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Helmut Gollwitzer. The English commentary is excellently supplied by Professor David Gushee, Martin Greschat and Andreas Pangritz. An eye-witness from those days, Rudolf Weckerling, now in his 90s, makes forthrightly apt comments, and the documentary is knit together by Bishop Wolfgang Huber of Berlin. Steve Martin tells me that he is now available to show this film to interested groups or churches. Contact Vital Visions, 171a Mitchell Road, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37830, USA.

JSC

1b) Hugo Brinkmann, God’s Ambassadors. The Bruderhof in Nazi Germany. Farmington, Pennsylvania, Robertsbridge, Sussex, England: Plough Publishing House. 2001.

Five hundred years ago, Jakob Hutter, a German Anabaptist, called on his disciples to follow the pattern of communal life described in the Acts of the Apostles, renouncing both violence and private property. These Hutterites were persecuted for their pious nonconformity and exiled. Eventually and much later, a few managed to establish colonies in remote rural areas of the United States and Canada, where they still survive.

In Germany, after the disastrous defeats of 1918, a lone but courageous and charismatic preacher, Eberhard Arnold, decided to revitalize Hutter’s ideas. He managed to establish a community, or Bruderhof, on a piece of run-down farmland in the hilly area of central Germany, near Fulda. His inspiring evangelical leadership attracted young idealists, longing to escape from the sinful world of war and capitalism, and including a number of young pacifists from Switzerland, Holland and Sweden. They eked out a living by looking after children in need, referred to them by the local authorities, or by peddling their handicrafts.

Arnold was well aware that such a ministry was both daunting and even dangerous. As he said: “To be an ambassador is something tremendous. It seems that we are nothing at all except what the King of God’s Kingdom would have us do. When we take this service upon us, we enter into mortal danger”.

This prediction was soon enough fulfilled after the Nazis took power in 1933. The Bruderhof aroused suspicion that it was a communist cell, and its declared pacifism antagonised its neighbours. Arnold’s open refusal to support the Nazis’ rearmament programme, and his declared opposition to the hate-filled antisemitism of the new regime, only led to open hostility. In November 1933, when he refused to endorse the national plebiscite requiring undying loyalty to Adolf Hitler, the result was predictable. A gang of Nazi thugs descended on the Bruderhof, searching everywhere for seditious literature or hidden armaments. By 1934 their school was forcibly closed, the foster-children’s support was cut off, their charitable status was revoked, and their assistance to homeless vagrants declared to be a menace to public order. Their economy was throttled. They were forced to evacuate their children to an Alpine refuge in Lichtenstein lest they be forcibly placed in a Nazified school.

Arnold’s apocalyptic theology had always led him to expect persecution, although he maintained a loyal attitude towards the state and its rulers. But he and his followers would not compromise on their basic beliefs. So inevitably tension rose steadily. Luckily he managed to preserve many of his sermons, addresses and letters to his supporters. These form the basis of this account, written by Hugo Brinkmann, of the Bruderhof’s sufferings at the hands of the Nazis. They have been excellently translated and published in a very small edition for an English audience by his American followers, Art and Mary Wiser, of Ulster Park, New York.

As the Nazis’ pressure on the churches to conform increased, the pastors and congregations were more and more caught in a clash of loyalties between their faith and their nation. For his part, Arnold fully shared Luther’s view of the two kingdoms: the state existed to control evil, if necessary by force; but the Church is within the sphere of absolute love. It must proclaim the spirit of unity and purity, but could have no truck with heathen Nazism.

This incompatibility became even clearer in March 1935 when Adolf Hitler reintroduced compulsory military service for all young men. In the Bruderhof, the memory of the earlier Hutterites’ sufferings for the cause of peace was evoked vividly. All the affected youth left at once for Lichtenstein, and were replaced by foreign nationals. But the Bruderhof’s prophetic witness to the power of Christian love and the need for non-violence and social justice was overwhelmed by the Nazis’ militaristic propaganda and preparations for a future war. The subsequent proclamation of the Nuremberg racial laws only increased Arnold’s sense of impending doom and disaster. And the community’s future was also imperilled by the lack of funds, the blatant hostility of the local authorities and its neighbours, and even by the failure of some of its members to live up to Arnold’s spiritual expectations.

In November 1935, Eberhard Arnold died in hospital after a botched operation to mend a broken legbone. A few months later Arnold’s successors decided to move the Bruderhof from both Germany and Lichtenstein to England. Although penniless, they were able to rent a farm property in the Cotswolds, and start all over again. Luckily the British authorities granted them refugee status and the Quakers came to their financial rescue. However, even in England, resentment and hostility against this tiny band of God’s ambassadors was evident. As the threatening clouds of war gathered, this group of Germans, pacifists and exiles was often isolated or at least cold-shouldered.

In Germany, in April 1937, by order of the Gestapo, the Bruderhof’s farm was compulsorily confiscated and the community dissolved. The few remaining members were expelled under guard, apart from three men detained in prison for alleged fraud. They were finally, after several months, released and packed off to Britain. The story of their escape to freedom makes a fitting close to this lively account of Hutterite obedience to the faith they had received and the sufferings they endured as a consequence.

JSC

1c) Rudolf Wentorf, Paul Schneider, Witness of Buchenwald, translated by Daniel Bloesch. Vancouver: Regent College Publishing 2008. 401 Pp. ISBN 978-1-57383-417-9.

Pastor Paul Schneider was murdered by the guards in Buchenwald concentration camp in July 1939. Subsequently he became commemorated as the first martyr of the German Evangelical Church to die at the hands of the Nazis. After the war his widow published a moving and widely read memoir, Der Prediger von Buchenwald, translated into English in an abbreviated version by Edwin Robertson in 1956. Luckily a much fuller biography was later published in Germany by Rudolf Wentorf, which included an almost day-to -day account of Schneider’s valiant and persistent defiance of the Gestapo and other Nazi agencies. Thanks to his assiduous research in police, state and church archives, Wentorf is able to reproduce contemporary documents which outline the Nazi tactics to get rid of this unwanted challenger to their supremacy. Schneider was a simple Rhineland pastor, who early on raised the flag of alarm at the readiness of his colleagues and parishioners to compromise with the ideological heresies of Nazism. From 1933 onwards Schneider’s steadfastness in defence of the Gospel, and his refusal to accept any deviance, was taken as a dangerous political protest by the local Nazi authorities. In fact, Schneider belonged to the wing of the Confessing Church which was largely apolitical, but staunchly dedicated to the truth upheld in the Church’s tradition. By 1937 his controversial stance, and the denunciation of some of his parishioners, had led the Gestapo to order his eviction from his parish. But he refused to leave, and, even when expelled forcibly, returned to his pastoral charge in order to fulfil his God-given responsibilities. The result was that in November 1937 he was sent to Buchenwald and placed in solitary confinement. But he there maintained his faithful witness by shouting out his prayers and sermons to any who could hear, and thus earned the description of the Pastor of Buchenwald.

It is therefore very welcome that Wentorf’s biography has now been republished for the first time in English by Regent College Publications, Vancouver, in an excellent translation by Daniel Bloesch. This makes available to a wider audience the story of Schneider’s resistance to the subtle and relentless pressure to conform imposed by the Nazis, as well as the horrendous stages of persecution which eventually led to his death. Though not as well known as Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Paul Schneider’s faithfulness will remain highly significant for all those who seek to learn from the lessons of Nazi Germany for the life and witness of the Church.

JSC

1d) Gabriele Kammerer, Aktion Sühnezeichen. Friedensdienst. Aber man kann es einfach machen. Göttingen: Lamuv Verlag 2008. 371 Pp. ISBN 978-3-88977-684-6

In 1945 only a handful of Germans was prepared to come to terms with the atrocities, violence and mass murders committed by their Nazi rulers in the preceding years, or to face up to their own collaboration and complicity. One of them was Pastor Martin Niemöller, newly released from eight years in concentration camps, who called his colleagues and parishioners to a mission of repentance. He became highly unpopular. And the 1945 Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt, of which he was a principal author, likewise aroused negative feelings among many churchmen. The vast majority of Germans took refuge in a blanket amnesia, looked for convenient alibis, and concealed their own participation in Nazi crimes.

It was therefore many years before the full extent of the German criminal activities, especially in Eastern Europe, became known, or the consequences recognized. Only then could more positive measures begin, seeking to restore Germany’s moral reputation. One of those most actively involved was Lothar Kreyssig, whose Christian motivation led him to seek reparation for the victims of German warfare and bloodshed. He was a Saxon provincial judge, and very active in church work. By the 1950s he had been elected as President of the German Evangelical Church’s National Synod, and was thus an influential member of the church hierarchy.

In 1958 he introduced a resolution calling on the Synod to support a programme whereby young Germans would spend a year in restoration work on behalf of the Nazis‚ victims, especially in Poland, the Soviet Union and the newly-established State of Israel. For Kreyssig, this was far more than a gesture of humanitarian goodwill. Rather it was to be a dedicated mission of reparation and reconciliation by which at least some practical measures of Christian solidarity could be expressed, especially across international borders. Too often after 1945 Germans had focussed attention on their own sufferings, and had ignored those they had inflicted on foreigners. Kreyssig was determined to put this right. He was particularly concerned to attack the self-righteousness of many Germans who had turned a blind eye to the Nazis‚ crimes. Even those who now claimed they had opposed Nazism all along should remember that they had not done enough to prevent these disasters in the first place.

This moral urge for reconciliation led Kreyssig to launch his idealistic scheme and to recruit a small band of self-conscious Christians to undertake works of practical service for the survivors in the victims‚ homelands. Only such concrete activist experiences could carry credibility, and also avoid any pretence at self-congratulation. Only thus could Germany’s moral reputation be restored, and the past crimes finally be atoned for.

Naturally such an endeavour met with bureaucratic difficulties, particularly from the communist countries, including Kreyssig’s own East German authorities, who suspected the intentions of such an explicitly Christian group. A more favourable response came from ecumenical partners in both Holland and Norway. The first group of volunteers went in August 1959 to northern Norway to construct a home for the mentally and physically handicapped. These first ventures were spontaneous but ill-prepared. Not enough care had been taken to ensure that the projects were feasible, or could be executed by well-meaning but ill-trained German youth. Too little contact had been established with the local authorities, both secular and church. There were the usual language difficulties, and personality clashes. But above all, these young people only partially caught on to Kreyssig’s vision of making them ambassadors of expiation, bearing the burden of Germany’s guilt. Many of these young people were not too enamoured of the explicit piety, with morning devotions, bible study, and evening worship, which were built into the programme. And as the years went by, it was increasingly difficult for these youngsters to feel a sense of remorse for crimes committed before they were born, and for which they felt no responsibility. Many, in fact, would cheerfully have undertaken the same kind of relief work if under secular auspices. In the long run Kreyssig’s hopes for a reinvigoration of dedicated churchmanship had to be laid aside. As Ms Kammerer notes, this German venture came to resemble other similar youth programmes such as the American Peace Corps or the British Voluntary Service Overseas, whereby the motive of reparation was replaced by reconstruction.

Inevitably Aktion Sühnezeichen was caught up in the polemics and politics of the Cold War. Kreyssig’s aim was to have his young helpers, recruited from both east and west, make a common witness for peace and reconciliation across the Iron Curtain. This hope was thwarted by the politicians. The East German teams were refused exit visas even to neighbouring Poland. Likewise the deep-rooted antagonisms between Germans and Poles, even in the churches, were not easily surmounted. The first Sühnezeichen group to undertake work in Auschwitz had to travel there individually and unobtrusively by bicycle. Their work of reconciliation in this camp was a small contribution towards changing the poisoned atmosphere in both church and politics. But it was still many years before similar resentments at home in Germany were overcome. Too often these small acts of Christian witness were attacked as “befouling their own nest” or “capitulating to the communists”. And the fact that Kreyssig and his staff were based in East Berlin, and hence, after 1961, unable to visit the projects undertaken by his West German supporters, only made for unavoidable tensions. In 1968 the first work-camp in the notorious Czech fortress of Theresientstadt was cut short by the invading Soviet troops. The message of reconciliation and peace seemed threatened by overwhelming political forces, even though now more than ever necessary.

The 1970s were a period of sobering reassessment. In East Germany Aktion Sühnezeichen was hobbled by the communist authorities, and its activities increasingly watched by the Stasi. Emphasis was placed on local work on behalf of the mentally or physically handicapped, on repair of Jewish cemeteries, or on pilgrimages to former concentration camps. In the western half of the country, greater freedom existed to promote the Aktion’s peace work. But it still aroused opposition from conservative circles. Only in the 1980s did the international consensus move towards support for peace through disarmament. But criticism also came from the Aktion’s own participants. Why did so many of these social action projects seemingly prop up the status quo, instead of radically altering the corrupting social structure? Why were the founder’s pious ideals not turned into prophetic political witness? Too often, it seemed Realpolitik guided the organization.

But the call of peace through reconciliation was too important to be abandoned. And in the 1980s new horizons opened up. In West Germany, Aktion joined with other peace groups to oppose NATO’s military policies; in East Germany, many Aktion participants were to be found in the peace groups which sprang up in local Protestant churches, and which eventually grew to be a significant political force. The overthrow of the communist regime in 1989 broke all previous patterns. After the 1990 reunification of the whole country, Aktion’s call for reconciliation was much needed, especially in the controversial union of the agency’s east and west branches. Its overseas projects were to be expanded into thirteen different countries, usually with the support of local governments and churches. But Christian solidarity with the victims of war and violence is still the group’s hallmark.

Gabriele Kammerer’s well-researched and incisively written account of the organization’s fifty years is amplified by a number of well-chosen photographs, identifying the individuals and projects involved. It is much to be hoped that an English translation could be produced, since the story of this courageous German agency for reconciliation and peace deserves to be widely known as an example for others.

JSC

2) Memorial Tribute to Bishop Bell

On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Bishop George Bell of Chichester, the following tribute was written by the German Evangelical Church’s Presiding Bishop, Wolfgang Huber of Berlin:

“Your work will never be forgotten in the history of the German Church”. This was the view of Dietrich Bonhoeffer writing to his friend George Bell, the Anglican bishop of Chichester in England in 1937. He had good reasons for such praise. No other foreign church leader had shown such a friendly and intensive, yet at times critical interest in the fate of the churches and of the Christians in Germany as had George Bell. He was a valiant campaigner for peace and truth, and did not hesitate to lend the authority of his office and personality to his convictions, including matters in the political sphere. He died on October 3rd fifty years ago – a very proper cause for remembrance.

George K.A. Bell was born on February 4th 1883, the son of a clergyman. After studying theology, he served for three years as a curate in the slums of Leeds. Then came several years as Chaplain and Tutor in Oxford until 1914 when he became the private secretary to the Archbishop of Canterbury, and was given the special responsibility for international and inter-church relations. During the first world war he was much engaged in interdenominational action on behalf of the war orphans, and then – together with Archbishop Nathan Soderblom of Uppsala, Sweden – was active in organising the exchange of prisoners-of-war. These experiences led Bell, after the war, to become a champion of collaboration with the Lutheran churches, a strong advocate of the nascent ecumenical movement, and an organiser of international theological exchanges. In 1929 he was appointed Bishop of Chichester, and also from 1932 to 1934 he was President of “Life and Work”, one of the main branches of the new ecumenical movement.

The Bishop of Chichester took an active interest in the German Church Struggle from the beginning. In April 1933 he expressed publicly the ecumenical movement’s concern about the early stages of the Nazi persecution of the Jews in Germany. In September he circulated a strong resolution against the introduction of the so-called Aryan Paragraph, discriminating against Jews, and its adoption by sections of the German Evangelical Church. He first met Dietrich Bonhoeffer at a conference in 1931, and when Bonhoeffer became Pastor for the German Churches in London in 1933, the two men developed a strong and trusting relationship. Bonhoeffer was in fact Bell’s principal source of information about events developing in Germany. For his part, Bell was assiduous in bringing this information to a wider British public, particularly through his frequent letters to the main newspaper The Times. In contrast to some sections of British public opinion and also some leading members of the Church of England, Bell took a strong stand from 1933 onwards in support of the Confessing Church in its struggle, and against all forms of fascism.

Early on, he began to organize measures to assist refugees from Germany. After he became a member of the House of Lords in 1937, he continually urged the British Government to give increased support for such persecuted people. It is possible to suppose that his timely reporting to the British public about the arrest and trial of Martin Niemöller prevented the latter’s murder in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

When the second world war broke out, Bell threw himself into activities designed to help the refugees fleeing the continent, and also the resident Germans interned in England, as well as for British conscientious objectors. Bell was no pacifist, but he decisively and publicly repudiated the tactic of area bombing of German towns, through his passionate speeches in the House of Lords. These speeches were a direct challenge to the British Government and to large sections of public opinion. It was a sign of Bell’s courage and moral determination that he was not deterred to state his opinions and take such an unpopular stand.

George Bell was one of the decisive figures in the post-1945 world who enabled the German churches to return to the ecumenical family. He was one of the first to go back to Germany in 1945 to show his friendship for those “true” Germans who had survived. He gave a most moving sermon in a church service in the heavily bombed Marienkirche in Berlin, and was clearly deeply moved to see the conditions of the refugees crowding the platforms of the Lehrter Station in Berlin. Only two months after the war’s end, he organized a Thanksgiving Service in memory of Dietrich Bonhoeffer in Holy Trinity Church, London. On this occasion he recounted to the congregation Bonhoeffer’s last message to his English friend: “Tell the Bishop that this is for me the end, but also the beginning of a new life. I believe with him in our universal Christian brotherhood which rises above all national interests”.

3a) Book note

Dick Pierard draws attention to a new book which he, together with Edwin Arnold at Clemson University, South Carolina, has translated and edited: Theo Lehmann, Blues Music and Gospel Proclamation. The Extraordinary Life of a Courageous East German Pastor, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, 2008. Born in 1934 and son of a distinguished German missiologist, Lehmann studied theology, was ordained and served as a pastor in a congregation in Chemnitz (then Karl-Marx-Stadt) of the Landeskirche of Saxony. An unabashed confessionalist, he also became a youth evangelist and incurred the constant wrath and surveillance of the State. Since reunification, he continues to work as an evangelist throughout Germany. His great interest in life is actually American black music – Negro spirituals, blues and jazz, and he published several things in the GDR on this topic, including a doctoral dissertation at Halle, “Negro Spirituals: Geschichte und Theologie,” which was then reprinted after reunification. His memoir, Freiheit wird dann sein: Aus meinem Leben, has sold widely in Germany. He is not shy of controversy and may not suit all opinions. But well worth reading.

CharRichP@aol.com

3b) L Stan and L.Turcescu, Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania, Oxford 2007. This husband and wife team of Romanian scholars, now both teaching in Canada, provides a useful survey of events in the religious sphere in Romania since the fall of its despotic, manic dictatorship in 1989. Romanians have been obliged to rethink and reshape all their public institutions so the churches have been engaged in what has proved to be a difficult struggle for self-identification and definition. The plurality of church life has been a barrier in the way of the Romanian Orthodox Church’s attempt to reclaim its position as the “national” or established church, and the legacy of its former subservience to the Communist regime still poisons relationships. Disputes over the property of other church bodies such as the long-forbidden Greek Catholics, have only made Romanian church life more complex and unsettled. Doubts remain about the Orthodox Church’s support for a democratic political society, as with its strong opposition to Romania’s joining the European Union, and its tactics in matters of education and morality give rise for concern.

JSC

4) Journal Issue: Religion, State and Society, Vol. 36, no. 3, September 2008 is devoted to six articles on the relations between religion and law in various settings, viz. The European Court of Human Rights, Bulgaria, Post-Communist Russia and Hungary, Spain, Australia and the Middle East. These papers deal with the constitutional and legal problems arising between various denominations as factors in the secular states in which they interact. The authors describe a range of models from strict separation to the established and historic church-state relationship still existing in certain countries.

With every best wish to you all,

John S.Conway

Wibbeling had just completed his theological examinations and practical training for the ministry when the First World War began. He fought, eventually becoming an officer, married shortly after the war ended, and was ordained in 1919. His subsequent career showed his lifelong commitment to the renewal and stability of his church as well as his own strong social-political convictions. His political leanings were socialist. He began his ministry as a youth pastor in the coal-mining town of Bochum in the Ruhr valley, where he reached out to working class, Catholic, socialist, and other youth organizations in the region, creating a coalition that focused especially on the problems of alcoholism among youth. A non-church colleague described him in those years as someone “who didn’t act like a pastor at all, avoided church language and was familiar with and understood the socialist movement.”

Wibbeling had just completed his theological examinations and practical training for the ministry when the First World War began. He fought, eventually becoming an officer, married shortly after the war ended, and was ordained in 1919. His subsequent career showed his lifelong commitment to the renewal and stability of his church as well as his own strong social-political convictions. His political leanings were socialist. He began his ministry as a youth pastor in the coal-mining town of Bochum in the Ruhr valley, where he reached out to working class, Catholic, socialist, and other youth organizations in the region, creating a coalition that focused especially on the problems of alcoholism among youth. A non-church colleague described him in those years as someone “who didn’t act like a pastor at all, avoided church language and was familiar with and understood the socialist movement.” Mit Herz und Verstand is one of his recent additions to the literature. In addition to the fine overview of the topic in the introduction by Gailus and co-editor Clemens Vollnhals, it consists of biographical and historical profiles of Agnes and Elisabet von Harnack, Elisabeth Abegg, Elisabeth Schmitz, Elisabeth Schiemann, Margarete Meusel, Katharina Staritz, Agnes Wendland and her daughters Ruth and Angelika, Helene Jacobs, Sophie Benfey-Kunert, Elisabeth von Thadden, and Ina Gschlössl.

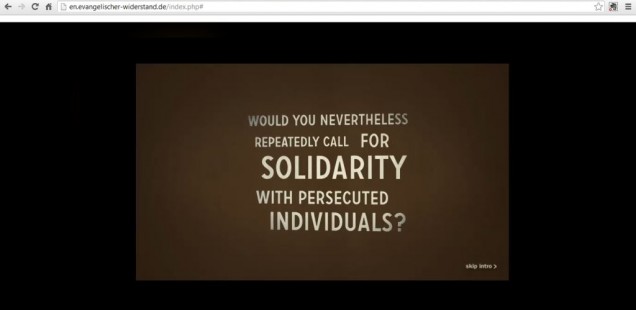

Mit Herz und Verstand is one of his recent additions to the literature. In addition to the fine overview of the topic in the introduction by Gailus and co-editor Clemens Vollnhals, it consists of biographical and historical profiles of Agnes and Elisabet von Harnack, Elisabeth Abegg, Elisabeth Schmitz, Elisabeth Schiemann, Margarete Meusel, Katharina Staritz, Agnes Wendland and her daughters Ruth and Angelika, Helene Jacobs, Sophie Benfey-Kunert, Elisabeth von Thadden, and Ina Gschlössl. The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” (

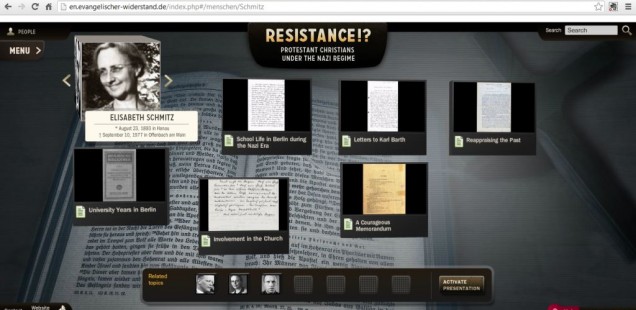

The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” ( This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.)

This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.) In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.”

In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.” A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship.

A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship. Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history

Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history