Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 26, Number 3 (September 2020)

Review of Lucia Scherzberg, Zwischen Partei und Kirche: Nationalsozialistische Priester in Österreich und Deutschland (1938-1944), Schriftreihe “Religion und Moderne” Band 20 (Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag, 2020). 645 pages, 49,00,- €, (44,99,- € E-Book), ISBN: 9783593444185.

By Kevin P. Spicer, Stonehill College

This review was originally published in theologie.geschichte and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the publisher. The original review is available here: http://universaar.uni-saarland.de/journals/index.php/tg/article/view/1154/1211.

In Zwischen Partei und Kirche, Lucia Scherzberg, professor of systematic theology at Saarland University and co-editor of Theologie.Geschichte, studies a relatively small group of Catholic priests and select laity from Germany and Austria who actively promoted a positive relationship between the National Socialist state and the Catholic Church. In the book’s introduction, among many questions, she asks, “Were they a few crazy fanatics? Were the members isolated or did they find their support in the rest of the clergy?” and “How much did the priests differ in their convictions and actions from the rest of the leadership of the Catholic Church?” (14). Scherzberg finds that though they were fanatical in their support for National Socialism, these Catholic clerics and laity were far from deranged. Rather, they were intelligent, intensely calculating, and fully cognizant of their actions in support of Hitler and the Nazi government and party. Yet, as Scherzberg reveals, at times, their outlook was not always exceptional when compared with some of their fellow clergymen. Still, they made the ill-advised mistake of imperiously bucking the Church’s hierarchical system by assuming roles and tasks traditionally reserved for the Church’s episcopate, and thereby became persona non grata in their dioceses.

As I have shown in Hitler’s Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism, there were approximately one-hundred-fifty “brown priests” who publicly supported and aligned themselves with National Socialism.[1] In my more broadly based work, I devoted a chapter to examining the National Socialist Priests’ Group (NS-Priests) studied by Scherzberg. By contrast, Scherzberg spent years researching the NS-Priests’ personalities, tracking down minute details, and uncovering extensive networks between and among them. Her research deepens our knowledge of the complexity of church-state relations under National Socialism and builds upon previous works such as Hitler’s Priests. Additionally, the pioneering studies of the late contemporary witness Franz Loidl, professor of church history at the Catholic-Theological Faculty of the University of Vienna, provided Scherzberg with a basic introduction to the NS-Priests that included vital primary documents, though the study was limited in scope and often apologetic in analysis.[2] Josef Lettl’s brief but impressive Diplomarbeit (Master’s Thesis), Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den religösion Frieden 1938 (Association for Religious Peace 1938), offered a general introduction to the initial but short-lived public organization of the NS-Priests.[3] More recently, in Hitlers Jünger und Gottes Hirten (Hitler’s Disciples and God’s Shepherds), Eva Maria Kaiser examined a few of the leading NS-Priests in her study of the Austrian bishops’ post-war advocacy for former National Socialists.[4] In the end, Scherzberg’s study is authoritative and will become a standard work.

As I have shown in Hitler’s Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism, there were approximately one-hundred-fifty “brown priests” who publicly supported and aligned themselves with National Socialism.[1] In my more broadly based work, I devoted a chapter to examining the National Socialist Priests’ Group (NS-Priests) studied by Scherzberg. By contrast, Scherzberg spent years researching the NS-Priests’ personalities, tracking down minute details, and uncovering extensive networks between and among them. Her research deepens our knowledge of the complexity of church-state relations under National Socialism and builds upon previous works such as Hitler’s Priests. Additionally, the pioneering studies of the late contemporary witness Franz Loidl, professor of church history at the Catholic-Theological Faculty of the University of Vienna, provided Scherzberg with a basic introduction to the NS-Priests that included vital primary documents, though the study was limited in scope and often apologetic in analysis.[2] Josef Lettl’s brief but impressive Diplomarbeit (Master’s Thesis), Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den religösion Frieden 1938 (Association for Religious Peace 1938), offered a general introduction to the initial but short-lived public organization of the NS-Priests.[3] More recently, in Hitlers Jünger und Gottes Hirten (Hitler’s Disciples and God’s Shepherds), Eva Maria Kaiser examined a few of the leading NS-Priests in her study of the Austrian bishops’ post-war advocacy for former National Socialists.[4] In the end, Scherzberg’s study is authoritative and will become a standard work.

Scherzberg uses the 1938 Anschluss to divide her work into two parts that contain headings but without chapter numbers. In the first part, Scherzberg identifies the original members of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den religiösen Frieden (AGF), the initial rendering of the NS-Priests that became public after the March 1938 Anschluss. The AGF consisted of both lay and ordained Catholics, primarily under the leadership of three individuals: Johann Pircher, a former religious of the Deutsch-Orden who had incardinated into the Vienna archdiocese in 1921 and joined the NSDAP in 1933; Wilhelm van den Bergh, a former Capuchin friar from the Netherlands who like Pircher had incardinated into the Vienna archdiocese in 1929; and Karl Pischtiak, a lay Catholic, National Socialist, and SA-Sturmbannführer who had ties with Josef Bürckel, Reichskommissar für die Wiedervereinigung Österreichs mit dem Reich (Reich Commissioner for the Reunification of Austria with the Reich;1938-1939) and Reichsstatthalter and Gauleiter of Vienna (Reich Governor and NSDAP District Leader; 1939-1940). According to Scherzberg, the AGF developed from the remnants of several Catholic pro-Anschluss groups. The same individuals had also been entangled in more politically aligned extreme right-wing associations such as the Katholisch-Nationalen (Catholic Nationals), the Deutsche Klub (German Club), and the Deutsche Gemeinschaft (German Community). Many of these same individuals had likewise been involved in the post-war Catholic youth movement, which had been heavily influenced by the writings of theologian Michael Pfliegler. Pfliegler criticized political Catholicism and emphasized the importance of the Church’s pastoral mission, especially to promote peace between church and state. Youth associations such as Reichsbund Jungösterreich, Bund Neuland, and Quickborn rejected the Peace Treaty of St. Germain-en-Laye (1919), supported a Greater-Deutschland, and embraced various forms of antisemitism, though generally not racial. Many of their members also rejected the Austrian Corporative State, especially the close alignment between the Austrian Catholic Church and the Dollfuß and Schuschnigg governments. Catholic priests from Styria, whose borders had been affected by the 1919 treaty, particularly rejected the situation of post-war Austria. Scherzberg provides a comprehensive overview of Austria’s pre-Anschluss history to contextualize the AGF’s foundation.

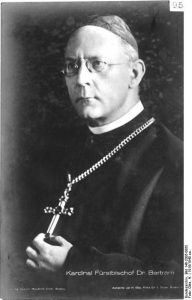

Before the 10 April 1938 National Referendum on the Anschluss, the Austrian bishops issued a solemn declaration that expressed their goodwill towards National Socialism. The Holy See, however, was not pleased by the stance of the Austrian episcopate, especially after the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge (With Deep Anxiety), that criticized the German state’s encroachment on the rights of the Catholic Church. On 8 April 1938, Schmerzensfreitag (Friday of Sorrows), many of the individuals who were predisposed to form the AGF, issued a letter directed to Cardinal Theodor Innitzer, archbishop of Vienna, in support of the Anschluss and critical of the Vatican. Eight days later, on 17 April, Pircher, van den Bergh, and two other priests in the name of the AGF issued a public appeal to the Catholic clergy to support the political developments between Austria and the German Reich. Newspapers covered it and reported that the appeal allegedly resonated with the clergy. Immediately, Jakob Weinbacher, Innitzer’s secretary, made it known that he did not approve. As early as May 1938, the Vienna Diözesanblatt (Diocesan Gazette) reminded clergy that they were not to be involved in politics and should limit their realm of activity to the pastoral sphere. On 30 September 1930, Cardinal Innitzer ordered diocesan newspapers to announce a ban against the AGF. Pircher and van den Bergh were never personally informed beforehand. In October 1938, Pircher issued a statement carried by Austrian newspapers that announced the disbandment of the AGF.

Scherzberg’s argument reveals that the prohibition was not due solely to a question of tactics or a difference of opinion about applying them that led to the AGF’s ban. Instead, one could attribute it more to the nature and function of the diocesan hierarchical structure, whereby only a bishop or his delegate speaks in the name of the Church. The ban also took place during a period of tense church-state conflict as the two sides negotiated for power in annexed Austria. With pressure on his back from the Holy See to assert the rights of the Church and to critique National Socialism, Innitzer could not allow a renegade group of priests to speak for his diocese. Pircher and van den Bergh were not alone. Pircher claimed that 525 priests were members, and an additional 1844 expressed their support (out of 8,000 priests in Austria). Scherzberg finds that these numbers may not be entirely overstated. Through meticulous research, she identifies at least 150 priests who joined the AGF and offers convincing arguments about the missing individuals not accounted for.

Around the time of the AGF’s prohibition, a power struggle ensued between Pircher and Pischtiak. Scherzberg speculates that Pischtiak used his connections with Bürckel to have the Gestapo confiscate the AGF’s membership index from its headquarters in Pircher’s home. At this point, it might have been helpful if Scherzberg had also analyzed the contemporary lay-cleric dynamics in this power struggle. Nevertheless, in the end, Scherzberg reveals that Pircher proved more skillful at power-play, apparently enjoying a more significant share of Bürckel’s trust. Pitschtiak then separated himself from the AGF and disappeared from the historical record.

Even though the AGF had formally disbanded, Pircher refused to let go of his dream to create a mass organization for priests within the NSDAP structure. Moving underground, Pircher maintained his contacts with like-minded priests. In a November 1938 letter to a former AGF member, he declared that the NS-Priests needed to retain, “‘reconciling, mediating, and state-affirming ideas [until] a modus vivendi can be achieved in religious terms’” (228). He was not alone. Pfarrer, Richard Hermann Bühler, a retired priest of the Limburg diocese, suggested that they establish an NS Religionsdiener-Verband (National Socialist Religious Servants Association) that would educate the clergy in a National Socialist spirit. Yet, in the disbanded AGF world, these efforts had little practical impact as the actual group of priests dwindled over time to a select few.

Amid this post-AGF climate, in December 1938, Pircher travelled to Cologne to meet for the first time Richard Kleine, a priest of the Hildesheim diocese and religion teacher at the Duderstadt Gymnasium. Though the specific origins of their initial contact are unknown, Kleine would become a leading figure among the NS-Priests as well as its primary theorist. Kleine’s entry along with others would also broaden the group’s geographic scope, enlarging it from its primarily Austrian locale to a broader demographic reach that would encompass the Greater German Reich.

Scherzberg’s research reveals a great deal more about Kleine than previous studies uncovered. To avoid scandal over Kleine’s illegitimate birth, he had to be ordained for Hildesheim instead of his home diocese of Cologne. Likewise, he was rejected as a Feldgeistlicher (military chaplain) in the First World War. While not overemphasizing these points, Scherzberg speculates that they had an impact on his self-perception and world outlook. Still, Kleine had further influences. His professor, Arnold Rademacher, a specialist in fundamental theology at the University of Bonn, advocated for both church reform and the reunification in faith among the Christian denominations. In the same vein, at University of Tübingen, Wilhelm Koch, professor of dogmatics and apologetics and a progressive intellectual, provided Kleine with a religious worldview that contrasted with the dominant neo-scholastic approach of his era. Accused of the heresy of modernism, Koch ended up leaving teaching and returned to full-time pastoral ministry. The impact of Rademacher and Koch on Kleine would especially be felt when Kleine raised issues that preoccupied him and shared them with members of the NS-Priests.

In addition to Pircher, Kleine, van den Bergh, and Bühler, other prominent members included Alois Nikolussi, a priest of the Trient diocese who in 1919 became a Chorherr of St. Augustine at Stift Sankt Florian; Simon Pirchegger, a priest of the Graz-Seckau diocese, a Dozent of Slavic Studies at University of Bonn, and an NSDAP member; Joseph Mayer, an Augsburg priest and professor of moral theology at Theologische Fakultät Paderborn; and Adolf Herte, a Paderborn priest and a professor of church history and patristics also at Paderborn. As Scherzberg’s previous works have also shown, Karl Adam, professor of systematic theology at the University of Tübingen, later joined this group.[5] A few Catholic laymen were also involved, including Josef Bagus, editor of the Kolpingsblatt, and Alois Brücker, an editor and NSDAP member living in Cologne. For each of these individuals, Scherzberg provides extensive background information to contextualize their support of National Socialism and initial contact with Pircher and Kleine. Additionally, she concludes the first part of her study by discussing the theological positioning of the group. The individual egos of the group’s members, along with the intermittent commitment of each, did not easily lead to consensus on religious questions. Pircher, for example, remained obsessed and convinced of the group’s ability to influence the outlook of high-ranking National Socialists on the Church. Kleine became fixated on an antisemitic interpretation of Christ’s Sermon on the Mount, interpreting it as a declaration of war on Judaism. Finally, Mayer and Herte appeared reluctant in their involvement, having to be nudged along by Pircher.

Part two of the work focuses on the activities of the NS-Priests, who never agreed on an official name for the group. The outbreak of war for Germany, with its decisive initial victories and subsequent harsh defeats, created a radicalization in the group’s outlook. Scherzberg’s systematic theological expertise is evident throughout her writing, especially in part two, as she analyzes the publications and presentations of the group’s members. Most chilling is the parallel she draws between the NS-Priests’ antisemitism, which led members to advocate the removal of references to Jews in Catholic sacramental rites, and the dormant antisemitism among members of a subcommittee dealing with liturgical reform in the Fulda Bishops’ Conference who discussed and similarly advocated for the removal of Jewish names from the marriage rite. Though the German bishops never agreed upon a revised rite for the sacraments under National Socialism, one did appear in 1948, with the Jewish names discussed above removed.

The ideas of the NS-Priests appeared in Kameradschaftlicher Gedankenaustausch (Comradely Exchange of Ideas; KG), a newsletter that ran inconsistently for twenty-seven issues from September 1939 to January 1945. With the help of a Catholic laywoman, Pircher edited and distributed each issue that typically was four pages in length. Pircher published most articles with pseudonyms. Nevertheless, Scherzberg spends significant time and does crucial detective work identifying the authors of the contributions. The KG’s language was overtly nationalistic and repeatedly implored its readers to serve their fatherland faithfully, especially in wartime. Increasingly in each issue, the KG’s language also became more militant and antisemitic. Alongside the KG, on his own initiative, from 1938-1940, Pircher wrote Information zur kulturpolitischen Lage (Information on the Church-Political Situation), mirroring the SD’s Meldungen aus dem Reich (Reports from the Reich), in which he reported on church issues that he believed would be of interest to the state. He shared the reports with Gauleiter Bürckel, who, it appears, for a brief time financially supported Pircher’s efforts. Despite their actions and National Socialist worldview, Pircher and Kleine had little sympathy for priests who proposed a more radical course for the Church’s clergy, such as abandoning clerical celibacy. Likewise, Pircher revealed his allegiance to Catholicism by including criticisms of the state’s treatment of the Catholic Church in his reports. He confided to Kleine that he might end up in Dachau for his more critical comments. Two separate party proceedings to remove Pircher from the NSDAP were eventually introduced, but neither succeeded.

The efforts of the NS-Priests brought them in contact with like-minded clergy and laity from other Christian denominations, and even in contact with representatives of völkisch non-Christian groups. Kleine pursued unification efforts with the Nationalkirchliche Bewegung Deutsche Christen (National Church Movement of German Christians; DC), and with the Völkisch-Religious Gemeinschaft (Ethnonationalist-Religious Community) nurtured by Ernst Graf von Reventlow from Postdam. Though Kleine at first was taken aback by the involvement of a few former Catholic clergymen in the DC, he soon adjusted and began to work with them. The dialogue that ensued led to a series of meetings where the participants attempted to work out the significant obstacles that existed between them. Scherzberg painstakingly analyses the discussion at these meetings and the individuals involved. Due to numerous factors, nothing of note resulted in the end. However, Kleine did receive an invitation from the Protestant biblical studies professor, Walter Grundmann, to join his Institut für Erforschung und Beseitgung des jüdischen Einflusses auf das deutsche kirchliche Leben (Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life), which he accepted. As a result, Kleine’s antisemitism became more radical and even at one point promoted an ecclesiastical solution parallel to the Final Solution of the Jewish Question.

Kleine’s work with the DC led him into contact with the Mecklenburg Landesbishof (state bishop) Walther Schultz, who was sympathetic to Klein’s ecumenical efforts. Kleine also sought a similar collaborator from the Catholic side and believed he had found one in the newly appointed archbishop of Paderborn, Lorenz Jaeger, a former Wehrmachtspfarrer (army chaplain). While a previous biography has been sympathetic to Jaeger’s choices under National Socialism[6], Scherzberg’s findings reveal that while Jaeger was staunchly nationalist and open to listening, in the end, he rejected Kleine’s efforts at a joint Protestant-Catholic Pastoral Letter and refused to sanction Kleine’s understanding of church and ecumenism. Yet, Kleine did succeed in bringing together Schultz and Jaeger to a meeting with him to discuss the pastoral letter. A research commission focusing on Jaeger is ongoing in the Paderborn archdiocese.

As the war turned for the worse for Germany, the NS-Priests became more embittered, and their antisemitism proportionally increased. In their voluminous correspondence, they condemned the 1943 Decalogue Letter, which was critical of the state and adopted by the plenary assembly of the Fulda Bishops’ Conference. Scherzberg concludes that the worsening of the war situation and the party’s dwindling attention and notice given to the NS-Priests led to this escalation. One might also perceive that the radical antisemitism was always present, and that the apocalyptic situation at the end of the war provided the impetus for the priests to express their views more openly and, in turn, attempt to prove their allegiance even more. After the war, most of the known members of the NS-Priests, centered around Pircher and Kleine went through some form of denazification and lost their positions. The lay members, less so. Yet, Scherzberg reveals that none dropped their racist National Socialist views, but instead, merely suppressed them.

In her introduction, Scherzberg offered a theoretical framework that included the sociological theories of (de)-differentiation, (de)-secularization, and (re)-sacralization, to understand and evaluate how the priests interacted with the church and state. She returned to this framework in her conclusion. For Scherzberg, the priests she studied lived in a differentiated and often secularized society, operating within their own independent sub-system. She continued, “They demanded freedom of religion, freedom of the church and freedom of conscience. In their understanding state and church were responsible for separate areas – the state for the welfare of the people, the church for the salvation of souls. Consequently, the members of the group consistantly rejected attacks by the state or the party on the church and the practice of religion” (599-600). Yet, in their own way and according to their values, the priests were traditional, upholding priestly celibacy and religious education. Often, they wanted the best of both worlds, rejecting political Catholicism while still hoping to influence political and social processes. At the same time, they were willing to accept the state’s oversight in areas such as the training of clergy.

Scherzberg also considered how the polycratic nature of the NS-State, especially evident in the leadership of Vienna’s Reichsstatthalter und Gauleiter Josef Bürckel and Baldur von Schirach, affected the NS-Priester. Like many Germans, the NS-Priester did not blame Hitler for the persecution of the Church. Instead, they relegated the responsibility to lower-level National Socialists or more likely than not to clergy themselves for not supporting the party and state. While not identifying state leadership style as polycracy, the NS-Priests attempted to benefit from the regionally differentiated leadership approaches at-large by courting Bürckel and Schirach with varying levels of success. Finally, Scherzberg considered the role that masculinity and comradeship played in the relational milieu that NS-Priests fostered. Most of the NS-Priests, for example, bought into the overtly militaristic language of the time, with some taunting or jeering the hesitancy of fellow priests to act, accusing the latter of a breach in masculinity. The comradely address shared between them and displayed boldly on their newsletter, however, ultimately had little weight as conflict and doubt arose among them. In the end, according to Scherzberg, they appear to be lone agents out for themselves and only brought together by a prevailing ideology. Each seemed willing to sell out the other, if necessary, to become more recognized by National Socialist leadership.

Lucia Scherzberg has produced an excellent study that should be widely read. It significantly helps the reader to understand the dangers of extreme nationalism and the temptation to misshape religion for personal and political gain.

Notes:

[1] Kevin P. Spicer, Hitler’s Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism, DeKalb, IL, 2008; vgl. „Gespaltene Loyalität. ‚Braune Priester‘ im Dritten Reich am Beispiel der Diözese Berlin“, übersetz. Ilse Andrews, Historisches Jahrbuch 122 (2002), S. 287-320.

[2] z.B. Franz Loidl, Religionslehrer Johann Pircher. Sekretär und aktivster Mitarbeiter in der ‚Arbeitgemeinschaft für den religiösen Frieden‘ 1938 (Vienna 1972); ders., Hg., Arbeitgemeinschaft für den religiösen Frieden 1938/1939. Dokumentation, 1. Teil (Vienna 1973); ders., Hg., Arbeitgemeinschaft für den religiösen Frieden 1938/1939. Ergänzungs-Dokumentation, 2. Teil (Vienna 1973).

[3] Lettl was a former student of Rudolf Zinnhobler, professor of church history at the katholische Privatuniversität Linz. Josef Lettl, Die Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den religiösen Frieden 1938, Diplomarbeit (Linz 1981).

[4] Eva Maria Kaiser, Hitlers Jünger und Gottes Hirten: Der Einsatz der katholischen Bischöfe Österreichs für ehemalige Nationalsozialisten nach 1945 (Wien/Köln/Weimar 2017).

[5] Lucia Scherzberg, Kirchenreform mit Hilfe des Nationalsozialismus. Karl Adam als kontextueller Theologe. (Darmstadt 2001) and ders., Karl Adam und der Nationalsozialismus (Saarbrücken 2011; theologie.geschichte, Beiheft 3).

[6] Heribert Gruß, Erzbischof Lorenz Jaeger als Kirchenführer im Dritten Reich. Tatsachen-Dokumente-Entwicklungen-Kontext-Probleme (Paderborn 1995).

As I have shown in Hitler’s Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism, there were approximately one-hundred-fifty “brown priests” who publicly supported and aligned themselves with National Socialism.

As I have shown in Hitler’s Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism, there were approximately one-hundred-fifty “brown priests” who publicly supported and aligned themselves with National Socialism. Friedrich Weißler is another such figure. A legal advisor to the Confessing Church, he is usually mentioned (if at all) in his connection to the 1936 Confessing Church memorandum (Denkschrift) to Adolf Hitler. Tortured and beaten to death in Sachsenhausen in February 1937, Weißler was the only person to be killed as a result of the memorandum. Not coincidentally, he was also the only “Volljude” involved. This 2017 book by Manfred Gailus is a gripping biography of a courageous man and a well-documented account of the genesis and aftermath of the memorandum. (Gailus is the first author to examine the papers that were in the family possession.)

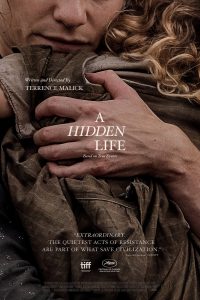

Friedrich Weißler is another such figure. A legal advisor to the Confessing Church, he is usually mentioned (if at all) in his connection to the 1936 Confessing Church memorandum (Denkschrift) to Adolf Hitler. Tortured and beaten to death in Sachsenhausen in February 1937, Weißler was the only person to be killed as a result of the memorandum. Not coincidentally, he was also the only “Volljude” involved. This 2017 book by Manfred Gailus is a gripping biography of a courageous man and a well-documented account of the genesis and aftermath of the memorandum. (Gailus is the first author to examine the papers that were in the family possession.) Malick is an atypical American director: he has protected his private life to the point of reclusiveness; his projects routinely consume several years; while he has made several critically-acclaimed films (his first film, Badlands; The Thin Red Line, about the Vietnam War; The Tree of Life, about immortality), he is both lauded and criticized for favouring themes and visual aesthetics over plot and narrative (see The Tree of Life). In fact, A Hidden Life delivers a more linear narrative than many of his films, with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end. It opens with Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, the famous aerial shot of clouds and a city gradually coalescing through the mist. Lasting only the first couple of minutes, and including splices from elsewhere in that famous 1934 documentary, such as the stunning panorama of the Nazi Party’s rally grounds, this is all Malick gives to the audience of Hitler’s climb to power and takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia before plunging directly into the fall of 1939. Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) is married to Franziscka (“Fani”, Valerie Pachner), and has two small blonde-haired, blue-eyed daughters. They live in the Upper Austrian village of Sankt Radegund, not far from the German border (Bavaria). We watch them pause in their labour as unseen planes fly overhead, our only clue that the war has begun.

Malick is an atypical American director: he has protected his private life to the point of reclusiveness; his projects routinely consume several years; while he has made several critically-acclaimed films (his first film, Badlands; The Thin Red Line, about the Vietnam War; The Tree of Life, about immortality), he is both lauded and criticized for favouring themes and visual aesthetics over plot and narrative (see The Tree of Life). In fact, A Hidden Life delivers a more linear narrative than many of his films, with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end. It opens with Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, the famous aerial shot of clouds and a city gradually coalescing through the mist. Lasting only the first couple of minutes, and including splices from elsewhere in that famous 1934 documentary, such as the stunning panorama of the Nazi Party’s rally grounds, this is all Malick gives to the audience of Hitler’s climb to power and takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia before plunging directly into the fall of 1939. Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) is married to Franziscka (“Fani”, Valerie Pachner), and has two small blonde-haired, blue-eyed daughters. They live in the Upper Austrian village of Sankt Radegund, not far from the German border (Bavaria). We watch them pause in their labour as unseen planes fly overhead, our only clue that the war has begun.