Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 25, Number 2 (June 2019)

Review of Thomas Brodie, German Catholicism at War, 1939-1945 (Oxford/NY: Oxford University Press, 2018), 288 Pp., ISBN: 9780198827023.

By Kevin P. Spicer, C.S.C., Stonehill College

In German Catholicism at War, Thomas Brodie, lecturer in twentieth-century European history at the University of Birmingham, has produced a valuable examination of Catholicism in Germany during the Second World War. Similar in approach to Patrick Houlihan’s World War I study, Catholicism and the Great War: Religion and Everyday Life in Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1922 (Cambridge, 2015), Brodie’s work aims to explore “Catholicism’s social, cultural, and political roles in German society during the Second World War” (3). Rather than tackle Catholicism in Germany as a whole, Brodie conducts a regional study focusing upon Catholics in the Rhineland and Westphalia, specifically in the archdiocese of Cologne and the dioceses of Aachen and Münster. He explains his selection by writing, “These regions represented heartlands of German Catholicism, with Cologne nicknamed the ‘German Rome’ and its archbishopric featuring the largest Catholic population of any in the Reich” (11). In these regions of the home front during the war, Brodie wishes to examine Catholic “devotional practices and confessional communities” (10) to understand “how far Catholics supported their nation’s war efforts as its genocidal dimension unfolded, and whether they were able to reconcile national, political, and religious loyalties over the tumultuous years from 1939-1945” (3-4).

According to Brodie, few scholars have dedicated attention to such questions. Certainly, Brodie is correct that there is no monograph that singularly examines Catholicism on the German Home Front during the Second World War. At the same time, he excludes from his bibliography studies by individuals such as Thomas Breuer, Ernst Christian Helmreich, and Heinrich Missalla, which have endeavored, at least, partially but perceptively, to address related issues. He also is quick to dismiss much of the recent historiography on the churches, deeming them too focused on the “German Churches institutional relationship with the Holocaust,” too preoccupied with “religious leaders and theologians,” and too often written in a “moralizing argumentative tone” (8). Brodie laments that many recent works on Germany under National Socialism, especially recent titles focusing on the German Volksgemeinschaft (national/racial community), have completely ignored the impact of religion on German culture and society. By contrast, Brodie sets out to build upon the works of Dietmar Süß (Death from the Skies, Oxford, 2014) and, his Doktorvater, Nicholas Stargardt, The German War: A Nation under Arms (London, 2015), which, as a part of their larger narrative, address the role religion played in German society during the Second World War.

From the outset, Brodie makes a series of claims that challenge much of the existing historiography on the Catholic Church under National Socialism. While the Church experienced restrictions and confiscation of its properties, Brodie asserts that its clergy was a part of the “national community” and not a “persecuted minority beyond its boundaries” (18). He notes, “In marked contrast to the Kulturkampf, no German Catholic bishop was imprisoned during the Third Reich” (18). Active resistance was “far from uniform” and only reflected “the commitments of individuals and small groups rather than a coherent trend across the milieu” (18-19). The Nazi leadership had no plans to “demolish” or “dismantle” the Churches after the war. More likely, Brodie suggests, “Hitler and Goebbels had less violent measures in mind,” such as the “withdrawal of state financial support” (17). Ultimately, Brodie insists that one cannot misleadingly describe the German Catholic milieu as an “impermeable” sub-culture and place it in juxtaposition against “anti-clerical” National Socialist leaders (20). Rather, one must conceive of the Catholic milieu as multi-faceted and permeable. Within it, existed individuals across the political and social spectrum. As Armin Nolzen finds (and Brodie quotes), “most members of the party and its auxiliary organizations were affiliated with the Christian Churches during the Third Reich” (20). Such definitive claims are provocative. Throughout the study, Brodie endeavors to defend them. At times, he succeeds; at others, he is less convincing. Still, he offers much for the reader to consider and for historians to explore further.

In his initial chapter, “Prologue 1933-1939,” Brodie introduces the reader to the history of church-state relations under National Socialism. Though Catholics had participated in Weimar democracy, Brodie explains that authoritarian thought had increasingly crept into Catholic intellectual discourse. He attributes this openness to conservative-authoritarian ideas primarily to the Church’s Neo-Scholastic theology, which he explains, “Located the evils of a godless modernity in the secularizing trends unleased within European society since the enlightenment and French Revolution” (24). Brodie’s use of Neo-Scholasticism is perhaps misplaced. He uses it again and again as if to explain the nature of the statements and pastoral letters of the bishops, to clarify the motivations of the Catholic clergy, and to describe reticent actions of Church leaders toward the state.

In general, Brodie makes little differentiation in his presentation of theology throughout his work and, in my opinion, does not fairly consider its implications. Perhaps, he would have done well to consult Robert Krieg’s Catholic Theologians in Nazi Germany (New York, 2004) or a similar study to learn more about the diversity of Catholic theology at that time. (To be fair, he does cite an article by Krieg, but this article is limited in scope and not as broad a work as Catholic Theologians.) Klaus Breuning’s classic study, Die Vision des Reiches (Munich, 1969), could also have assisted Brodie more convincingly to contextualize his analysis of Catholic intellectual-theological bridge-building with National Socialism. Instead, Brodie writes, “The Nazi regime enjoyed considerable support among Catholic intellectuals, both clerical and lay, in the Rhineland and Westphalia during its initial years of power” (25). Such sweeping statements are not helpful in his otherwise insightful analysis.

According to Brodie, the initial years of National Socialist rule experienced little tension in church-state relations. Even the 1934 murder of Erich Klausener, the leader of Catholic-Action in Berlin, during the Röhm Purge, or the increasing number of infringements against the Reich-Vatican concordat does not warrant much concern. Recalling Ian Kershaw’s insight, Brodie writes, “Catholics extensively believed that Nazi anti-clerical policies were the work of Party radicals, and deemed Hitler innocent of involvement in their introduction” (26). A valid point indeed. Yet, such analysis enables Brodie to understate state-church tensions and to emphasize the nationalism of Catholics. For Brodie, Catholics proudly exhibited their nationalism as the National Socialist state remilitarized the Rhineland, gave assistance to the nationalists in the Spanish Civil War, and annexed Austria. Catholics deeply longed to be a part of the “national community” and eagerly supported its endeavors. In the latter 1930s, this even led Catholic clergymen “to defend the Catholic Church from hostile Nazi propaganda” by downplaying “the faith’s Jewish heritage” and by stressing its “national reliability” instead (28).

While these are legitimate facts, they are perhaps presented one-sidedly while ignoring the wealth of studies on Catholic resistance. Yet, even in the face of a definitive thesis, Brodie does point out that there is evidence Catholics did not as a whole support violence toward Jews during Kristallnacht nor did they condone increased tensions in church-state relations in the latter 1930s. Brodie concludes his prologue – a pattern he follows in each chapter – by leaving space for conflicting interpretations, stating, “Relations between German Catholics and the Nazi regime were accordingly complex on the eve of the Second World War in summer 1939” (30).

In Chapter One, “The Years of Victory, 1939-1940,” Brodie investigates how German Catholics responded to the outbreak of war in Poland and German victory in France. In comparison to the enthusiasm for war shown by the bishops in 1914, in general, the Catholic hierarchy in the Rhineland and Westphalia were generally more reserved and focused on the “fulfillment of duty and a “swift end to the conflict” (33). If anything, the bishops viewed the war “in universal terms as a divine punishment for sinful, secular humanity” (35). Brodie attributes the bishops’ interpretation to the influence of Neo-Scholastic theology but also points out that there was an exception to this outlook. Bishop Clemens August von Galen of Münster, for example, made statements and produced pastoral letters that incorporated forceful language with “overtly nationalist sentiments,” a trait he continued throughout the war, even into the post-war period (33). In this observation, Brodie confirms the arguments first put forward by Beth Griech-Poelle, which have been unfairly maligned by Joachim Kuropka and his Münsterland colleagues (primarily in German language works).

In their statements and letters, the bishops were myopic, almost self-centered, focusing on the “future fate of the Church in Germany,” not the “current situation in Poland” (37). They showed no concern for their Polish confreres, even though the Bishop of Katowice had sent at least two reports about the plight of the Polish clergy to the Fulda Bishops’ Conference. Michael Phayer first emphasized this fact, though Brodie does not cite him at this point in his narrative. If anything, German Catholics only showed sympathy toward co-religionist Polish forced laborers in their midst. (Again, Brodie makes this point without referencing the pioneering work of John J. Delaney on this subject.) In general, German Catholics showed little or no concern toward the plight of the Poles under Nazi occupation. The greater concern for the bishops and clergy was the August 1939 Nazi-Soviet pact and how it might impact the Church. Yet, despite this development, the German hierarchy, lower clergy, and laity continued to support the German state, especially after the fall of France in June 1940. The bishops even placed the resources of Caritas, the German Church’s charity organization, at the disposal of the Reich government.

Toward the end of the first chapter, Brodie emphasizes the impact antisemitic propaganda had on Rhineland and Westphalian Catholics. As evidence, he cites antisemitic and nationalistic articles from the Kolpingsblatt that he admits is “hardly representative of episcopal policy” (54). In turn, Brodie discusses the response to the 1939 lecture on the German Catholicism by theologian Karl Adam, a priest of the Regensburg diocese, who called for closer alignment between German nationalism and Roman Catholicism. While ignoring much of the existing historiography on Adam, Brodie fixates on a Düsseldorf Gestapo report that describes how Adam’s lecture had enthused younger clergy but produced opposition from the German hierarchy and more ultramontane-inclined older clergy. Brodie makes much of this statement, especially the insight he believes it offers on the response to the lecture among parish priests and Catholic laity. For him, this response is an example of the permeability of the Catholic milieu and the divisions that existed among the clergy in relation to acceptance and rejection of National Socialism. Unfortunately, Brodie can offer no further evidence to substantiate the Gestapo report nor can he present additional substantial evidence when he returns in chapter three to similar points of tension among the clergy.

Chapter Two, “Confrontation and its Limits,” focuses primarily on the three widely known sermons delivered by Bishop von Galen in the summer of 1941, following a period of intense church-state conflict. Brodie regrets that in the past the examination of von Galen has focused on “a moralizing debate concerning Galen’s individual status as a resister of Nazism” (65). Indeed, the bishop’s words were clear and stood in contrast to the “highly abstract and intellectual Neo-Scholastic language normally” used by the bishops in their pastoral letters; yet, Brodie insists they cannot be viewed as “articulations of outright opposition to the Nazi regime” (71-72). Instead, Brodie argues, Galen “skillfully positioned his protests within mainstream German nationalist opinion” (73). As such, German Catholics could agree with them, especially as many Catholics had first-hand witnessed the confiscation of monastic and Church properties. Similarly, fearing the forced euthanasia of their own institutionalized family members or wounded sons coming back from the battlefield, lay Catholics could easily relate to the bishop’s criticisms of the T-4 euthanasia policy. Despite such agreement, Brodie uncovers criticism recorded by SD and Gestapo agents from individuals who worry that von Galen has “undermined the home front” (81). Such concerns were quickly forgotten as Brodie reports that the sermons had little lasting effects, at least according to the Gestapo. By late fall, both the state and von Galen had reached a modus vivendi as Goebbels noted in his diary in mid-November, “The theoreticians in the Party must be put back in their cupboards” (86-87). Similarly, by late 1941, German Catholics “viewed their chief priority as securing their place inside the ‘national community’” (92). According to Brodie, this also meant that Catholics were not going to protest the state’s persecution of Jews.

Chapter Three, “The War Intensifies, December 1941-June 1944,” examines Catholic response to the war from the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941 and the subsequent onset of systematic murder of the Jews through German military defeat at the battle of Stalingrad in early 1943 and the D-Day invasion of June 1944. The German hierarchy’s responses follow established general patterns. No longer playing the role of a resister, in March 1942, von Galen issued a pastoral letter for Heroes’ Memorial Day, which praised the fallen against Bolshevism as “Christian martyrs in a ‘Crusade’ against ‘a satanic ideological system” (95). Frings of Cologne did his best to “avoid confrontation with the Nazi authorities,” even though past scholars have portrayed the bishop as a resister. In December 1942, Frings did issue a pastoral letter, The Principles of Law, meant to confront the state’s racial policy, but its “abstract intellectual” language failed to sway Catholics in any significant manner. Frings’ response was indicative of the stances taken by most of the German bishops. Even though faced with accurate reports on the mass murder of Jews, they remained indecisive and at odds with each other on how to respond. Though this issue has been exhaustively investigated by Antonia Leugers in Gegen einer Mauer: bischöflichen Schweigens (Frankfurt am Main, 1996), Brodie does not cite her but relies on more general sources for his narrative.

Over the course of 1942, the Nazi state lessoned its anti-clerical policies. This change did not go unnoticed by the bishops or the clergy. Still, the parish clergy, who had to deal with the regime daily on the ground level, maintained a “special hostility towards individual members of the Nazi regime” who, they believed, were behind anti-clerical measures (100). Their anger was frequently directed at Himmler and the SS and not toward the German government and, therefore, according to Brodie, betraying the “self-interested perspectives of the clergy, with the Nazi regime’s anti-clerical record being the primary source of their discontent, not its genocidal and imperial projects under way in eastern Europe” (101). Once the anti-clericalism subsided, Brodie argues that clergy were more accommodating of the regime. Utilizing a case study of two priests from Corpus Christi parish in Aachen, Brodie arrives at the far-flung conclusion that clergy who resisted or consistently held “negative attitudes towards the Nazi state and wider war” were in the minority (104), offering little nuance in his analysis. As evidence, he turns to the case of Dr. Johann Nattermann(es), a priest of the Cologne archdiocese, who gave outright support to the war. Brodie seems to have no knowledge of Nattermann’s pro-Nazi sympathies, his pro-National Socialist work with the Kolping Association, or his contributions to a 1936 pro-Nazi publication, Sendschreiben katholischer Deutscher an ihre Volks- und Glaubensgenossen.

After the February 1943 surrender of the Sixth Army at Stalingrad, the mood of the Catholic population and clergy toward the war changed. The bishops continued to support the war but also increased the language of sin and judgment in their pastoral letters. Meanwhile, the Gestapo and SD received frequent reports about unrest among the parish clergy whose criticism of the war appeared to be growing. Lay Catholics, too, complained, often about their bishops, especially for not condemning Allied bombing of Germany and for admonishing Catholics not to resort to language of “revenge.” In the end, Brodie’s analysis attempts to support dual interpretations, as he writes, “Whereas many Catholic clergymen and members of the laity were increasingly pessimistic concerning the war’s development, others continued to believe in, and hope for, German victory” (120).

Chapter Four, “Religious Life on the German Home Front,” examines the impact of the war on parish and diocesan church life on the home front. Brodie does not agree with the conventional historiography that posits an increase in piety and religiosity as German Catholics retreated inwardly in the face of total war. By contrast, Brodie portrays a gradual break-down of diocesan and parish structures that supported Catholics’ faith. While, soon after the war began, the number of withdrawals from official Church membership (Kirchenaustritt) decreased, at the same time, the number of young men entering the seminary also substantially decreased, especially with general mobilization. State laws, such as the October 29, 1940 air raid ordinance for religious services, placed restrictions on the public practice of religion. Such measures limited the availability of Masses for Catholics and thus affected religious practice.

Still, Brodie finds evidence of lay Catholics turning to their priests for guidance and protection during air raids, such as requesting the presence of clergy strategically positioned throughout air raid shelters. Other Catholics turned to religious medallions and devotions for solace during Allied bombing. What existed of parish activity was often championed by lay women Catholics who maintained their religious practices and parish involvement. Despite the state attempting to limit religious practice and even organize state funerals for victims of bombing, Brodie argues that “local parish priests remained for most Catholics a primary source of comfort in times of bereavement” (162). Funerals, he argues, should not be interpreted as promoting “defeatist sentiment or overt cultural retreat from Nazism,” but presented opportunities for an “overlap between Catholic ritual and Nazi ideology,” both which supported the state (163). In certain areas, such as Cologne, clergy and Nazi authorities cooperated to provide “mass public funerals for air-raid victims” (164). Brodie stresses that, “Catholic piety did not so much afford a space for cultural retreat from Nazism, as contribute to a ritual performance of national solidarity and victimhood, co-existing with the iconographies and languages of the NSDAP as well as older nationalist traditions” (165).

Chapter Five, “The Catholic Diaspora – Experiences of Evacuation” is an excellent chapter that breaks new ground in its description of the evacuation experience of Catholics to escape Allied bombing. As Brodie explains, Catholics from western Germany were temporarily relocated to Thuringia, Saxony, Brandenburg, and lower Silesia. Many of these areas were heavily Protestant and unwelcoming, or even hostile, to Catholics. In addition, as one National Socialist Welfare official commented on the relocation of Catholic children, “Finally we can get our hands on the children and separate them from the priests” (173). Though the western dioceses sent priests to minister to the transplanted Catholics, the task for the clergy was daunting. Geography was one of the main factors preventing contact between clergy and laity with some priests being required to cover wide stretches of territory often using poor public transportation. Many other obstacles existed. Such challenges led priests to describe their pastoral tasks in “martyrological language.” Brodie believes the use of such language prepared the clergy later to adopt it to explain their “self-understanding as victims of Nazism,” once the war ended (191).

In the sixth chapter, “Of Collapses and Rebirths,” Brodie recounts the well-documented post-war experience of the German Catholic hierarchy. As the Catholic Church’s infrastructure lay in ruins, the German bishops sought to find redemption. One path they chose was embracing the language of suffering as Brodie explains, “By evoking Christ’s passion and the Book of Job as metaphors to make sense of the fate befalling the Catholic Heimat, Frings and Galen strengthened and legitimized Catholic Germans emerging self-understanding as innocent victims of the war” (208). Such analysis offers evidence of the singularity of Brodie’s theological interpretation.

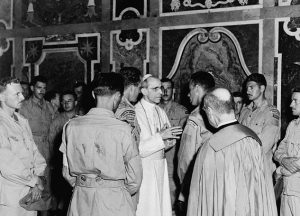

As the Allied troops moved eastwardly, the local clergy often became trusted contacts. Goebbels cynically noted this fact in a March 8, 1945 diary entry (224). After the conflict ended, the German bishops publicly promoted the language of victimhood and rejected collective guilt. Pope Pius XII supported such efforts to promote the image of a suffering German Catholicism by elevating Frings and von Galen to the college of cardinals soon after the war ended. Even Bernard William Griffin, Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, contributed to this interpretation by inviting Cardinal Frings to preach in London’s Westminster Cathedral in September 1946. Frings’ homily focused on the “severe persecution” the Catholic Church in Germany” had endured under National Socialism (225). Whatever ground the Church had lost under National Socialism, it seems to have regained it in post-war Germany.

Brodie has produced a helpful study of the German Catholic Church at war. For it, he has consulted an impressive array of church and state archival sources. Most interesting is his use of clerical Gestapo V-Männer reports held in the North-Rhineland-Westphalian State Archive (Rhineland Division) to ascertain the climate of both ordained and lay Catholics. Brodie is cautious in his use of this material and generally informs his reader of its use, especially when analyzing and drawing conclusions. Often such reports are the only avenue by which to gauge the opinion of lay Catholics. Brodie does supplement such reports with quotes from published and unpublished diaries, memoirs, and letters of both ordained and lay Catholics. All of this, he weaves together in an engaging and insightful narrative. His bibliography is extensive, but something about his sources does not sit right with me. At key points in the narrative, as I have pointed out above, he seems to be neglectful or unaware of important secondary sources, especially those focusing specifically on the Catholic Church in Germany under National Socialism. By contrast, his integration of more secularly based secondary works is impressive and contextualizes his study well into the historical events of Germany under war. At times, Brodie’s terminology is odd for a study on German Catholicism, referring: to a “curate” as a “trainee clergyman” (49); to a “religious community” as “holy orders” (67); to a “seminarian” as a “trainee priest” (135); to a newly appointed pastor as a “trainee pastor” (136); to “rectory” as a “parochial house” (146); to a “Vicar General” as a “General Vicar” (223). I know that I might sound punctilious, but I link this concern to Brodie’s ubiquitous use of Neo-Scholasticism to explain repeatedly clerical theological motivation. From the outset, Brodie makes it clear that he does not wish to engage in moralizing, but in the end, he has produced a sententious narrative that in itself does not fully elucidate the multifaceted nature of Catholicism under National Socialism.

Though these occurrences are notable in nature and unique in theological understanding, they share a supernatural commonality that O’Sullivan recounts as events of “miraculous faith” (4). O’Sullivan rightly argues that historians, even those who specialize in church history, have for too long neglected incidents of miraculous faith in their analysis of German history. In his fascinating study, O’Sullivan endeavors to fill this void. For him, miraculous faith events both reflect and intensify the institutional, political, cultural, and gender tensions within German Catholicism.

Though these occurrences are notable in nature and unique in theological understanding, they share a supernatural commonality that O’Sullivan recounts as events of “miraculous faith” (4). O’Sullivan rightly argues that historians, even those who specialize in church history, have for too long neglected incidents of miraculous faith in their analysis of German history. In his fascinating study, O’Sullivan endeavors to fill this void. For him, miraculous faith events both reflect and intensify the institutional, political, cultural, and gender tensions within German Catholicism. The suppression of the Bruderhof in Nazi Germany was not unobserved in Britain: there were protests and interventions by figures as diverse as the eminent Anglican laymen Sir Wyndham Deedes and the Baptist internationalist J.H. Rushbrooke. Friends of all kinds now proved effective, particularly in practicalities. By May 1936, the Bruderhof could be found in a farm near Ashton Keynes in the Cotswolds where a new community comprised sixteen Germans, fourteen British friends, and one Austrian. At the height of its quiet prosperity there, in October 1939, the community included as many as 119 Germans, 116 British members, 30 Swiss, 17 Austrians, and stray individuals from the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, France, Sweden, Italy, and Turkey. All came with their own stories and for their own reasons. All sought to be useful. A miner from the coalfields of Durham cycled three hundred miles to join them and was promptly set to work picking potatoes; another new arrival was a Lancashire poultry farmer who was also a Methodist lay preacher and admirer of the Indian Christian mystic Sundar Singh. In choosing the Cotswolds, a deeply rural area which possessed something of the character of an English arcadia, the community chose well. Birmingham, the second city of the country and a bastion of Quakerism and Free church life and worship, was not far away. Ashton Keynes also had a railway station. Visitors and longer-term guests could come and go as they chose – and they did.

The suppression of the Bruderhof in Nazi Germany was not unobserved in Britain: there were protests and interventions by figures as diverse as the eminent Anglican laymen Sir Wyndham Deedes and the Baptist internationalist J.H. Rushbrooke. Friends of all kinds now proved effective, particularly in practicalities. By May 1936, the Bruderhof could be found in a farm near Ashton Keynes in the Cotswolds where a new community comprised sixteen Germans, fourteen British friends, and one Austrian. At the height of its quiet prosperity there, in October 1939, the community included as many as 119 Germans, 116 British members, 30 Swiss, 17 Austrians, and stray individuals from the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, France, Sweden, Italy, and Turkey. All came with their own stories and for their own reasons. All sought to be useful. A miner from the coalfields of Durham cycled three hundred miles to join them and was promptly set to work picking potatoes; another new arrival was a Lancashire poultry farmer who was also a Methodist lay preacher and admirer of the Indian Christian mystic Sundar Singh. In choosing the Cotswolds, a deeply rural area which possessed something of the character of an English arcadia, the community chose well. Birmingham, the second city of the country and a bastion of Quakerism and Free church life and worship, was not far away. Ashton Keynes also had a railway station. Visitors and longer-term guests could come and go as they chose – and they did. In just 13 pages Manfred Gailus gives an overview of the Christian churches and religious identity and practice in Germany during the 12 years of Nazi rule. Rather than placing the Kirchenkampf and an assessment of the Catholic hierarchy at the centre of this narrative, Gailus paints a picture in which several diverse religious groups quarreled and competed with each and with the state. In addition to the Deutsche Christen, the Confessing Church, and the Catholic Church, he discusses the Free Churches, other small independent religious communities (Adventists, Quakers, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc.), and völkisch ‘new pagan’ groups (including the German Faith Movement and the Ludendorff movement). These völkisch-religious groups, whose proponents were called “German Believers,” need to be differentiated from the similarly-named “Believers in God” (a new label for those ardent Nazis who had left the church).

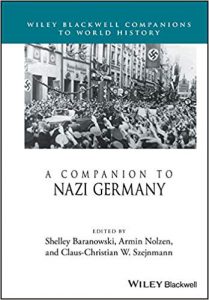

In just 13 pages Manfred Gailus gives an overview of the Christian churches and religious identity and practice in Germany during the 12 years of Nazi rule. Rather than placing the Kirchenkampf and an assessment of the Catholic hierarchy at the centre of this narrative, Gailus paints a picture in which several diverse religious groups quarreled and competed with each and with the state. In addition to the Deutsche Christen, the Confessing Church, and the Catholic Church, he discusses the Free Churches, other small independent religious communities (Adventists, Quakers, Jehovah’s Witnesses, etc.), and völkisch ‘new pagan’ groups (including the German Faith Movement and the Ludendorff movement). These völkisch-religious groups, whose proponents were called “German Believers,” need to be differentiated from the similarly-named “Believers in God” (a new label for those ardent Nazis who had left the church).

This sense of observing and interpreting like a guest whose eyes are being opened by degrees to something new and unexpected is certainly one of the strengths of the book. It makes Newell himself something of a tourist – in the best sense – and equally an attractive introducer to readers coming to the same questions afresh. The vital presence at the heart of the story is the pastor of the Nikolaikirche himself, Christian Führer, who in 1989 opened the doors of the church to all people – and, in particular, to many who were disaffected by the Communist state – so that they could meet together, light candles, share what was important to them all and find new ways to insist upon these things in a world of repression and intimidation.

This sense of observing and interpreting like a guest whose eyes are being opened by degrees to something new and unexpected is certainly one of the strengths of the book. It makes Newell himself something of a tourist – in the best sense – and equally an attractive introducer to readers coming to the same questions afresh. The vital presence at the heart of the story is the pastor of the Nikolaikirche himself, Christian Führer, who in 1989 opened the doors of the church to all people – and, in particular, to many who were disaffected by the Communist state – so that they could meet together, light candles, share what was important to them all and find new ways to insist upon these things in a world of repression and intimidation. In Reading and Rebellion in Catholic Germany, Jeffrey Zalar likewise boldly challenges the existing historiography concerning the German Catholic milieu and its culture of reading, a topic that perhaps is less central to historians of modern Germany, but still important, nevertheless. For those who study religious history, especially that of the Catholic Church in Germany, Zalar’s findings have major implications for understanding the inner-workings of the Catholic milieu. For years, historians have portrayed the milieu as “an insular subculture, whose boundaries were policed by an authoritarian clergy” (8).

In Reading and Rebellion in Catholic Germany, Jeffrey Zalar likewise boldly challenges the existing historiography concerning the German Catholic milieu and its culture of reading, a topic that perhaps is less central to historians of modern Germany, but still important, nevertheless. For those who study religious history, especially that of the Catholic Church in Germany, Zalar’s findings have major implications for understanding the inner-workings of the Catholic milieu. For years, historians have portrayed the milieu as “an insular subculture, whose boundaries were policed by an authoritarian clergy” (8). Griech-Polelle begins with the rise of religious antisemitism—rooted in the concept of Jews as “Christ-killers’’—in the biblical accounts of Jesus’ arrest, death, and resurrection. With the emergence of Christianity came the belief that the Early Church was the “New Israel” which replaced the Jews as God’s chosen people (10-11). Tracing the loss of Jewish rights in the late Roman Empire, the author shows how the Codex Theodosianus began to impose restrictions on Jews and to generate the segregating language that would shape the medieval era. Through the period of the crusades and on into the Middle Ages, Griech-Polelle explains important incidents in the history of Jewish persecution, but beyond that, she endeavours to outline the way a particular kind of antisemitic language emerged in, for example, tropes like the Wandering Jew or the blood libel. A short section on Thomas Aquinas shows how he built on Augustine’s notion of the preservation of the Jews as a witness to the truth of both the Hebrew scriptures and the Christian gospels, adding that the Jews were people with souls that needed to be saved. “Somehow, Jews were to be converted voluntarily—despite the persecutions and horrendous depictions of Jews as being in league with the devil, desecrating the Host, and reenacting the crucifixion of Jesus” (20). This chapter on the history of religious antisemitism continues with the medieval expulsions of Jews from various European countries and follows the story through the Renaissance and Reformation, the emergence of a substantial Jewish community in Poland, and the impact of the Enlightenment, French Revolution, modern nationalism, and post-1848 reactionary politics. It closes with the persecution faced by Jews in Tsarist Russia.

Griech-Polelle begins with the rise of religious antisemitism—rooted in the concept of Jews as “Christ-killers’’—in the biblical accounts of Jesus’ arrest, death, and resurrection. With the emergence of Christianity came the belief that the Early Church was the “New Israel” which replaced the Jews as God’s chosen people (10-11). Tracing the loss of Jewish rights in the late Roman Empire, the author shows how the Codex Theodosianus began to impose restrictions on Jews and to generate the segregating language that would shape the medieval era. Through the period of the crusades and on into the Middle Ages, Griech-Polelle explains important incidents in the history of Jewish persecution, but beyond that, she endeavours to outline the way a particular kind of antisemitic language emerged in, for example, tropes like the Wandering Jew or the blood libel. A short section on Thomas Aquinas shows how he built on Augustine’s notion of the preservation of the Jews as a witness to the truth of both the Hebrew scriptures and the Christian gospels, adding that the Jews were people with souls that needed to be saved. “Somehow, Jews were to be converted voluntarily—despite the persecutions and horrendous depictions of Jews as being in league with the devil, desecrating the Host, and reenacting the crucifixion of Jesus” (20). This chapter on the history of religious antisemitism continues with the medieval expulsions of Jews from various European countries and follows the story through the Renaissance and Reformation, the emergence of a substantial Jewish community in Poland, and the impact of the Enlightenment, French Revolution, modern nationalism, and post-1848 reactionary politics. It closes with the persecution faced by Jews in Tsarist Russia.