Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 25, Number 4 (December 2019)

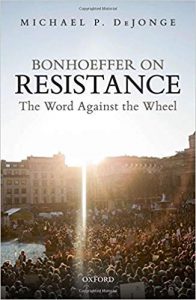

Review of Michael P. DeJonge, Bonhoeffer on Resistance: The Word against the Wheel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). 170 Pp. ISBN: 9780198824176.

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

Michael P. DeJonge’s book on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s theo-political vision of resistance is a concise response to recent conflicting invocations of a “Bonhoeffer moment” by both conservative and liberal Christians in the United States. Concerned about the lack of clarity concerning the legacy of Bonhoeffer’s political resistance and the narrow focus at present on Bonhoeffer’s involvement in the conspiracy to commit tyrannicide, DeJonge argues that “to associate his legacy exclusively with this conspiracy dramatically truncates his witness.” Indeed, “his participation in a conspiracy that intended violence was the endgame of a long resistance process, the final stop through an elaborate flowchart of resistance activity” (5). The author wants us to turn to Bonhoeffer for more than just inspiration for contemporary political activism. To that end, he seeks to go beyond narrating what Bonhoeffer did in order to ask what Bonhoeffer actually thought about political resistance, and to locate that within Bonhoeffer’s theology of church, politics, and resistance. In doing this, DeJonge seeks to fill a gap in the scholarly literature—the lack of a “comprehensive and accessible account of Bonhoeffer’s resistance thinking” (7).

In fourteen short chapters, DeJonge guides his readers through Bonhoeffer’s theology of resistance, identifying no less than six types of resistance in the German theologian’s writings. The author begins with basic theological foundations—creation, fall, and redemption—then adds the Lutheran accents of the law and gospel, explaining them in terms of the categories of preservation and redemption. He then outlines Bonhoeffer’s belief in politics as a component of God’s preserving activity, complete with Bonhoeffer’s criticisms of politics as an order of creation (with linkages to Natural Law, an aberration he associates with Roman Catholics and with “pseudo-Lutherans” who see the Volk as an order of creation) or as an order of redemption (with links to the Kingdom of God, which he associates with the Reformed tradition and the “mistake” of treating the gospel as a blueprint for society) (31-34). Rather, as DeJonge argues, Bonhoeffer uses the Lutheran theological mainstays of the two kingdoms and the orders as a way to define and hold down a middle position in which state and church (along with the household) work together in the task of preserving and redeeming humankind (38).

In fourteen short chapters, DeJonge guides his readers through Bonhoeffer’s theology of resistance, identifying no less than six types of resistance in the German theologian’s writings. The author begins with basic theological foundations—creation, fall, and redemption—then adds the Lutheran accents of the law and gospel, explaining them in terms of the categories of preservation and redemption. He then outlines Bonhoeffer’s belief in politics as a component of God’s preserving activity, complete with Bonhoeffer’s criticisms of politics as an order of creation (with linkages to Natural Law, an aberration he associates with Roman Catholics and with “pseudo-Lutherans” who see the Volk as an order of creation) or as an order of redemption (with links to the Kingdom of God, which he associates with the Reformed tradition and the “mistake” of treating the gospel as a blueprint for society) (31-34). Rather, as DeJonge argues, Bonhoeffer uses the Lutheran theological mainstays of the two kingdoms and the orders as a way to define and hold down a middle position in which state and church (along with the household) work together in the task of preserving and redeeming humankind (38).

Important to DeJonge’s account is Bonhoeffer’s insistence that the law and gospel, the orders, and the work of church and state needed to be reconnected in his time—brought back into cooperative harmony—having drifted apart into two entirely different sets of norms and values in the modern era. Drawing on Bonhoeffer’s 1932 lecture “The Nature of the Church,” DeJonge explains Bonhoeffer’s thinking about church and state as orders working together—the state to preserve external righteousness and create space for the service of Christ, which is the church’s specialized role. (45, 54). The church, for Bonhoeffer, is where Christ is truly present and where Christ is proclaimed through the preaching of the Word. Because Christ is lord over the whole world—including both church and state—and because the God’s Word (meaning both Christ’s presence and Christ preached) is of utmost importance, the church must be on guard to protect its role: “Obedience to the state exists only when the state does not threaten the word. The battle about the boundary must then be fought out!” (45). This idea is so central to DeJonge’s account of Bonhoeffer’s theology of resistance that it is worth quoting him at length here:

This remarkable understanding of the church’s proclamation is the anchor of Bonhoeffer’s resistance thinking. For him, the most powerful form of political resistance is not any action in the ordinary sense of that word, whether that action comes in the mild form of nonviolent civil disobedience or in the drastic form of violent governmental overthrow. Rather, the most powerful form of political resistance is words, although these are words in a special sense, words that are themselves, paradoxically, the most fundamental kind of action. This is, specifically, the divine word entrusted to the church. This word is the centre of Bonhoeffer’s resistance thinking and activity. When Bonhoeffer advocated or himself undertook any other form of resistance, it was in the service of this ultimate form of resistance. Because the word is the highest form of resistance, the church is the most important agent of resistance (48).

Chapters 5 through 14 analyze Bonhoeffer’s resistance thinking in a series of key texts written between 1932 and 1943, during the time of the Nazi dictatorship and the German Church Struggle: “The Church and the Jewish Question” (1933), “What is Church?” (1933), “The Führer and the Individual in the Younger Generation” (1933), “On the Theological Foundation of the Work of the World Alliance” (1932), “False Teaching in the Confessing Church?” (1935-1936), “The Church and the Peoples of the World” (1934), Discipleship (1937), Ethics (1940-1943), “Protestantism without Reformation” (1939), “State and Church” (1940s), “’Personal’ and ‘Objective’ Ethics” (c. 1942), “State and Church” (c. 1941), “After Ten Years” (1943), “History and Good” (1940s), “The Concrete Commandment and the Divine Mandates” (1943), and “What Does It Mean to Tell the Truth?” (1943). Along the way, he identifies three phases of Bonhoeffer’s resistance activity and six forms of resistance in Bonhoeffer’s writing (9-10, 59). In the first phase, from 1932-1935, in which Bonhoeffer engaged in “resistance through the proclamation of the ecumenical church” (9), four types of resistance stand out: 1.) individual and humanitarian resistance to state injustice, 2.) the church’s diaconal service to the victims of state injustice, 3.) the church’s “indirectly political word” to the state, and 4.) the church’s “directly political word” against an unjust state (10). In the second phase, from 1935-1939, Bonhoeffer returned to Germany, entered the “second battle” of the church struggle, and engaged in a new form of resistance: 5.) resistance through discipleship in the church. Finally, in the third phase of his resistance, from 1939-1945, Bonhoeffer entered the conspiracy to overthrow Hitler, and a final type of resistance: 6.) resistance through the responsible action of the individual (9-10).

As he works his way through these writings, phases, and types of resistance, DeJonge argues that Bonhoeffer was remarkably consistent in his understanding of resistance. He suggests that some of the confusion over seemingly contradictory statements made by Bonhoeffer—especially in “The Church and the Jewish Question”—can be reconciled through a proper grounding of the German theologian’s resistance thinking in his theology of the two kingdoms, the orders, and the relationship between church and state. The main problem, according to DeJonge, is that readers of Bonhoeffer (scholars included) have failed to attend to Bonhoeffer’s distinction between individual and humanitarian resistance on the one hand and churchly resistance on the other (59-68, passim).

Individual and humanitarian resistance are manifest in the first and sixth types of resistance identified by DeJonge. In the first type, as “The Church and the Jewish Question” makes clear, individuals and humanitarian groups (but not the church) can point out the specific injustices of state policies, “to make the state aware of the moral aspect of the measures it takes … to accuse the state of offenses against morality” (63-64).

The church, however, does not critique the state based on morality but based on the gospel. The church preaches and hears the gospel, and is defined by the presence of Christ (in conjunction with the proclamation of Christ, the message of the gospel) (62). But the church has both a preaching office and a diaconal office, and thus the second type of resistance (and the first offered by the church) is the diaconal “service to the victims of the state’s actions”—the work to “bind up the wounds of the victims beneath the wheel” (66). This is accompanied by two other types of resistance (numbers 3 and 4 in DeJonge’s typology) arising from the preaching office of the church: the “indirectly political word of the church,” which flows from Bonhoeffer’s notion of the church “questioning the state as to the legitimate state character of its actions, that is, making the state responsible for what it does” (69); and the “directly political word of the church,” which is rooted in Bonhoeffer’s belief that in extreme circumstances the church might act “not just to bind up the wounds of the victims beneath the wheel but to seize the wheel itself” (79). These are not about challenging the state directly concerning the morality of specific policies or actions, but about working to define the boundary of state authority and calling the state to fulfill its God-given mandate to preserve external righteousness. Even in the extreme case (the status confessionis, or state of confession), the church is not usurping the role of the state, but offering a “concrete commandment” in a specific situation in which the state has overstepped its bounds (82-87). The goal of type 3 and 4 resistance is, to quote Bonhoeffer, to “protect the state from itself and preserve it.” As DeJonge puts it, “The goal of the concrete commandment is to reestablish ordinary times in which the state and church fulfill their respective mandates” (87). It is essential to note that DeJonge returns time and again to the importance of the two kingdoms and the orders, or divine mandates, as Bonhoeffer comes to call them, for judging both the actions and the legitimacy of the state, and for defining the responses of the church.

To continue with DeJonge’s schema, type 5 resistance is the last of the churchly forms of resistance. It is the resistance that dominated the period in which Bonhoeffer directed the illegal Confessing Church seminary at Finkenwalde, where he engaged in what he called the second battle of the church struggle, the battle to see the church enter into genuine discipleship to Jesus. This radical discipleship would in turn provide it with the spiritual foundation from which to speak the indirect and direct words of the church to the state (109-119). It is the idea of discipleship as resistance, an entrance into the suffering of Christ and into suffering for Christ. For Bonhoeffer, only the community radically devoted to Christ belongs to the body of Christ. Indeed, Bonhoeffer even argued that membership in the Confessing Church—the only true church—was a requirement for salvation (124).

Finally, with phase 3 and type 6 of Bonhoeffer’s resistance, DeJonge argues that Bonhoeffer leaves behind churchly resistance and returns to the resistance of individuals or groups. This last resistance is the resistance of individuals willing to take “free responsible action” in the world (142-143), to enter into extreme situations in which normal standards of guilt and innocence do not apply, because the ordinary relationship of the two kingdoms or the orders/mandates of church and state have been thrown into confusion (152-154). Such resistance accepts the fact that “it is impossible to avoid guilt and complicity” (154). Again, as in the church’s resistance, this free responsible action of the individual is directed to one aim: to re-establish the conditions of life—to return to the place where the two kingdoms and divine mandates are once again working in harmony (155).

As DeJonge identifies these types of resistance in Bonhoeffer’s life and writing, one of the thorny problems he tries to solve is Bonhoeffer’s seemingly contradictory statements about Jews. Chapter 9 is devoted to this specific issue—to understanding how Bonhoeffer can argue that the church has an “unconditional obligation toward the victims of any societal order, even if they do not belong to the Christian community,” but continue on to state that:

The church of Christ has never lost sight of the thought that the “chosen people,” which hung the Redeemer of the world on the cross, must endure the curse of its action in long-drawn-out suffering. “The Jews are the most miserable people on earth. They are plagued everywhere, and scattered about all countries, having no certain resting place” (Luther, Table Talk). But the history of suffering of this people that God loved and punished will end in the final homecoming of the people of Israel to its God. And this homecoming will take place in Israel’s conversion to Christ. (100-101)

DeJonge rejects the notion that this is a case of an inconsistent, early version of Bonhoeffer “working out his thinking about Jews and resistance on the fly” (101). Rather, DeJonge argues that “the relationship between the mistreatment of the Jews and resistance to the state is not immediate but rather mediated by other concerns. Specifically, these concerns are the two kingdoms (as illustrated in the first part of “The Church and the Jewish Question”) and justification (as illustrated in the second part)” (101-102). Within the context of these concepts, Jewish persecution is, then, first and foremost an issue of the state failing in its divinely-ordained mandate, and in two ways: first, in failing to provide enough order to protect the rights of its people (and to which the church must respond unconditionally, on behalf of Jews), and second, in overreaching its authority and encroaching on the church’s freedom to proclaim the gospel (for the salvation of all, including the Jews) (105-108).

In his conclusion, DeJonge attempts to clarify Bonhoeffer’s thinking about rights (“inviolable rights are not fundamental”), the state (state authority is grounded not in popular sovereignty but in God’s mandate), and the church (the church’s political voice focuses on the state’s mandate and does not follow the “ethical-political logic” of individuals or humanitarian groups) (158-159). He reminds us that, for Bonhoeffer, the most fundamental action is not found in “our own deeds” but in “God’s word” (159). His hope is that his readers will understand that, for Bonhoeffer, the church is at the heart of his resistance thinking, and that “seizing the wheel” is not about civil disobedience or overthrow.

DeJonge has engaged in a thorough analysis of Bonhoeffer’s resistance thinking. Those of us who work on the historical side of the German church struggle would do well to incorporate his and other theologians’ insights into our work, to enrich our interpretations and aid us in the cultivation of an undistorted and unpoliticized interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s life and work.

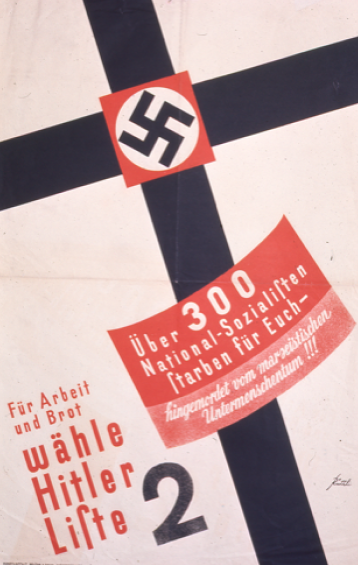

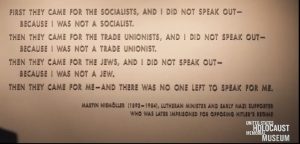

After remarking on the power, universality, and timelessness of the Niemöller quotation Brown-Fleming explained how Niemöller—though he is often held up as an opponent of Nazism—began as a supporter of the Hitler movement. Born into a monarchic, nationalist home, he served as a naval officer during the First World War and also held the typical antisemitic stereotypes of his day, seeing Jews as the Christ-killers and as outsiders in German society. Niemöller voted for the Nazis in several elections between 1924 and 1933 and read Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf. He resonated with Nazism and believed Hitler could bring God and country together into a powerful union.

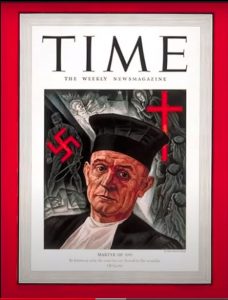

After remarking on the power, universality, and timelessness of the Niemöller quotation Brown-Fleming explained how Niemöller—though he is often held up as an opponent of Nazism—began as a supporter of the Hitler movement. Born into a monarchic, nationalist home, he served as a naval officer during the First World War and also held the typical antisemitic stereotypes of his day, seeing Jews as the Christ-killers and as outsiders in German society. Niemöller voted for the Nazis in several elections between 1924 and 1933 and read Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf. He resonated with Nazism and believed Hitler could bring God and country together into a powerful union. Time magazine featured Niemöller on its cover in 1940, as a symbol of the church, which it described as the sole domestic opponent to Nazism. Indeed, as Brown-Fleming explained, people from all around the world prayed for Niemöller and sent letters to him in the concentration camp.

Time magazine featured Niemöller on its cover in 1940, as a symbol of the church, which it described as the sole domestic opponent to Nazism. Indeed, as Brown-Fleming explained, people from all around the world prayed for Niemöller and sent letters to him in the concentration camp.

In fourteen short chapters, DeJonge guides his readers through Bonhoeffer’s theology of resistance, identifying no less than six types of resistance in the German theologian’s writings. The author begins with basic theological foundations—creation, fall, and redemption—then adds the Lutheran accents of the law and gospel, explaining them in terms of the categories of preservation and redemption. He then outlines Bonhoeffer’s belief in politics as a component of God’s preserving activity, complete with Bonhoeffer’s criticisms of politics as an order of creation (with linkages to Natural Law, an aberration he associates with Roman Catholics and with “pseudo-Lutherans” who see the Volk as an order of creation) or as an order of redemption (with links to the Kingdom of God, which he associates with the Reformed tradition and the “mistake” of treating the gospel as a blueprint for society) (31-34). Rather, as DeJonge argues, Bonhoeffer uses the Lutheran theological mainstays of the two kingdoms and the orders as a way to define and hold down a middle position in which state and church (along with the household) work together in the task of preserving and redeeming humankind (38).

In fourteen short chapters, DeJonge guides his readers through Bonhoeffer’s theology of resistance, identifying no less than six types of resistance in the German theologian’s writings. The author begins with basic theological foundations—creation, fall, and redemption—then adds the Lutheran accents of the law and gospel, explaining them in terms of the categories of preservation and redemption. He then outlines Bonhoeffer’s belief in politics as a component of God’s preserving activity, complete with Bonhoeffer’s criticisms of politics as an order of creation (with linkages to Natural Law, an aberration he associates with Roman Catholics and with “pseudo-Lutherans” who see the Volk as an order of creation) or as an order of redemption (with links to the Kingdom of God, which he associates with the Reformed tradition and the “mistake” of treating the gospel as a blueprint for society) (31-34). Rather, as DeJonge argues, Bonhoeffer uses the Lutheran theological mainstays of the two kingdoms and the orders as a way to define and hold down a middle position in which state and church (along with the household) work together in the task of preserving and redeeming humankind (38).