Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 21, Number 2 (June 2015)

Papal Rescue in Wartime Rome: A New Documentary and Commentaries

By William Doino Jr.

On April 1st, a documentary was televised in Italy entitled, “Lo vuole il Papa” (The Pope Wants It), exploring the role Pius XII played during the German occupation of Rome, when thousands of Jews were given shelter by Catholic institutions in and around Vatican City. The film is based upon the enterprising work of historian Antonello Carvigiani, who cites new evidence indicating Pius XII personally supported these rescue efforts.

Last year, Carvigiani published a scholarly essay, “Aprite le porte, salvate i perseguitati,” (“Open the Doors, Save the Persecuted,”) published in Nuova storia contemporanea (September-October, 2014) one of Italy’s leading academic journals.

In his essay, Carvigiani examined the histories of several female religious communities in wartime Rome, and– analyzing the texts and records they left behind– found evidence that each acted under a common directive of Pius XII to take in persecuted Jews and other endangered people. Though some critics of Pius XII have questioned whether such instructions were ever given, Carvigiani maintains that he has “found evidence of a written or oral order” which was “delivered to all religious houses in Rome, as well as to all parishes and ecclesiastical structures.”

The documentary, based upon Carvigiani’s essay, expands upon his findings, with new testimony of individuals connected to these wartime events.

Dr. Andrea Tornielli, one of Italy’s leading Vatican commentators and author of a major biography on Pius XII, praised the documentary: “The story of the docu-film is not told by a narrator but by the actual images and testimonies of two survivors, only boys at the time, and by the nuns of the cloisters who had heard from the older sisters what had happened….The director chose to concentrate on the cloisters of SS Quattro Coronati, Santa Susanna, and Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori, and the community of the Istituto di Maria Bambina, whose walls still harbor diaries and chronicles handwritten by the people at the heart of the stories. All of them vouch that the call to offer charity and refuge to the persecuted came from above. Written and oral testimonies refer repeatedly to the Pope, but also to the Deanery of Rome or to Giovanni Battista Montini [the future Pope Paul VI] and close collaborator with Pius XII.”

The aim of Carvigiani’s documentary is “not to be apologetic,” writes Tornielli. Rather, it is to “shed light on an, until now, little-known aspect of it.”

In the war diary of the community of Maria Bambina, continued Tornielli, “every day there was another request [and] every so often a telephone call from the Secretariat of His Holiness from the Vatican, and the reason was always the same: someone on the run, a persecuted family to take in, to protect, to help. One could not have refused a request from the representatives of the Pope…”

The wartime diary of the Augustinian Nuns of the convent of the Santi Quattro Coronati, first publicized in 2006, is one of the most explicit on record regarding Pius XII’s assistance. Relating events in the Fall of 1943, we read:

“Having arrived at this month of November, we must be ready to render services of charity in a completely unexpected way. The Holy Father, Pius XII, of paternal heart, feels in himself all the sufferings of the moment. Unfortunately, with the Germans entry into Rome which happened in the month of September, a ruthless war against the Jews has begun, whom they wish to exterminate by means of atrocities prompted by the blackest barbarities. They round up young Italians, political figures, in order to torture them and finish them off in the most tremendous torments. In this painful situation, the Holy Father wants to save his children, also the Jews, and orders that hospitality be given in the convents to these persecuted, and that the cloisters must also adhere to the wish of the Supreme Pontiff….”

In the register of the cloister of Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori, we read: “At this time, Jews, fascists, soldiers, caribinieri and nobility sought refuge with religious institutions, who, at great risk to themselves, opened their doors to save human lives.” This was the desire of Pius XII, “who was the first to fill the Vatican with refugees, using the Villa of Castel Gandolfo and the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran.”

The reference to Castel Gandolfo is significant, since many historians have overlooked, or are unaware that Pius XII protected many refugees there, including Jews. During the war years, contemporaneous reports put the number of refugees at Castel Gandolfo at 10,000 or more desperate and frightened people who were clothed, fed and protected there (a number of women even gave birth). Moving pictures of the overflowing refugees survive, and highlight one of the Church’s most significant humanitarian accomplishments during the War.

Of special significance is a dispatch published in the June 22, 1944 issue of the Palestine Post (today’s Jerusalem Post), from a correspondent reporting directly from Vatican City, just weeks after the liberation. Under the headline, “Sanctuary in the Vatican,” the correspondent wrote:

“Several thousand refugees, largely Jews, during the weekend left the Papal Palace at Castel Gandolfo–the Pope’s summer residence near Marino–after enjoying safety there during the recent terror. Besides Jews, persons of all political creeds who had been endangered were given sanctuary at the palace. Before leaving, the refugees conveyed their gratitude to the Pope through his majordomo.”

Since only Pius XII had the authority to open the doors of Castel Gandolfo, it is unreasonable to maintain that these “several thousand refugees, largely Jews,” were given aid only by other Catholic officials, acting without a clear directive from Pius XII. The sincere gratitude expressed by Jews in Vatican City that day was not misplaced, but given to the man who had supreme authority over Castel Gandolfo, Pius XII, who obviously made their survival possible.

Carvigiani’s new research and documentary is consistent with the testimonies of priest-rescuers like Cardinals Paolo Dezza and Pietro Palazzini (honored by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations) and Msgr. John Patrick Caroll-Abbing, who testified to Pius XII’s active support for the Jews of Rome, and to their rescuers. (There is also evidence and testimony that Pius helped the famous anti-Nazi Irish priest, Msgr. Hugh O’Flaherty, as well). Carvigiani also builds upon the work of noted historians Michael Tagliacozzo, a survivor of the Nazi raid on Rome’s Jews, and one of the outstanding authorities on it; Andrea Riccardi, author of L’inverno piu lungo, 1943-1944: Pio XII, gli ebrei e I nazista I Roma (The Longest Winter, 1943-1944: Pius XII, the Jews and the Nazis in Rome, 2008); Anna Foa, Professor of Modern History at the University of Rome; and Sr. Grazia Loparco, who has done extensive research on papal rescue in Rome. Foa has written: “Precisely with regard to Rome, the ways in which the work of sheltering and rescuing the persecuted was carried forward were such that they could not have been simply the fruit of initiatives from below, but were clearly coordinated as well as permitted by the leadership of the Church.” Similarly, Sr. Loparco has stated: “From the documentation and testimonies emerges evidence of the full support and instruction of Pius XII…Many concrete events, such as the opening of monasteries and convents, prove the fact that many Jews were lodged because of the direct concern of the Vatican, which also provided food and assistance.” More recently, Loparco has written an article entitled, “An Order from the Top,” for the Osservatore Romano, (English-language edition, January 30, 2015) in which she gives additional evidence of specific instances where papal instructions were given to rescue persecuted Jews in Rome.

It should also be noted that, after the liberation of Rome but before World War II ended, Vatican Radio was already broadcasting the life-saving assistance of the Holy See. A review of Pius XII’s charity was broadcast on March 12, 1945 and stated: “During the occupation of Rome, between 8th September, 1943 and 5th June 1944, he gave shelter in 120 institutes for women and 60 institutes for men, as well as in other houses and churches in Rome, to more than 5,200 Jews who were thus able to live free from fear and misery.”(Cited in Reginald F. Walker, Pius of Peace (London: M.H. Gill and Son, 1945), p. 94).

No examination of the Vatican and the German occupation of Rome would be complete without a careful study of the most important primary documents available; such a collection has fortunately been produced by Pier Luigi Guiducci, in his work, Il terzo Reich contro Pio XII: Papa Pacelli nei documenti nazisti (The Third Reich Against Pius XII: Pope Pacelli in Nazi Documents). Though not yet translated, Professor Guiducci has given an interview in English revealing his findings.

While scholarly research continues around the record of Pius XII during the Holocaust and doubtless will be further assisted when the Vatican releases its remaining wartime archives, it is encouraging that researchers like Carvigiani have brought forth fresh evidence which provides a more complete and balanced picture of Pius XII’s pontificate.

The cover announces the character of the theme: it is the image of a stained glass window in Worcester Cathedral showing three resolute figures looking up towards the sky, intent, devout, broadly sanguine. One is a nurse and the other two are men of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. The task that David Nash has set himself here is a striking one: in what kinds of narratives might the historian find the relationship between religious faith and active public life in the British twentieth century? How are we to locate the dimension of personal faith in the discussions and dramas of society at large? How are we to know when it is there – or when it is not?

The cover announces the character of the theme: it is the image of a stained glass window in Worcester Cathedral showing three resolute figures looking up towards the sky, intent, devout, broadly sanguine. One is a nurse and the other two are men of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. The task that David Nash has set himself here is a striking one: in what kinds of narratives might the historian find the relationship between religious faith and active public life in the British twentieth century? How are we to locate the dimension of personal faith in the discussions and dramas of society at large? How are we to know when it is there – or when it is not? The opening chapter, written by two Oxford scholars, examines the taxonomy of recent English Evangelicalism, describing the various strands within this spectrum of belief, which share common features in their adherence to the key truths of justification by faith alone and the supreme authority of Holy Scripture as the word of God. Nevertheless each of these strands places its emphasis on different aspects of the faith. Conservative Evangelicals stress the inerrancy of the Bible and refuse to accept the scientific evidence for evolution. More “open” Evangelicals have accepted both the modern theories about the world’s origins and many of the findings of biblical criticism, while most recently the contribution of the charismatic movement, drawn from Pentecostalism, and found in such London churches as Holy Trinity, Brompton or St Paul’s, Onslow Square, has reinvigorated and popularized Evangelicalism among young people. The rivalries—and sometimes the acerbic criticisms of these groups of each other—have meant that English evangelicalism often seems to have been in a constant process of reconfiguration.

The opening chapter, written by two Oxford scholars, examines the taxonomy of recent English Evangelicalism, describing the various strands within this spectrum of belief, which share common features in their adherence to the key truths of justification by faith alone and the supreme authority of Holy Scripture as the word of God. Nevertheless each of these strands places its emphasis on different aspects of the faith. Conservative Evangelicals stress the inerrancy of the Bible and refuse to accept the scientific evidence for evolution. More “open” Evangelicals have accepted both the modern theories about the world’s origins and many of the findings of biblical criticism, while most recently the contribution of the charismatic movement, drawn from Pentecostalism, and found in such London churches as Holy Trinity, Brompton or St Paul’s, Onslow Square, has reinvigorated and popularized Evangelicalism among young people. The rivalries—and sometimes the acerbic criticisms of these groups of each other—have meant that English evangelicalism often seems to have been in a constant process of reconfiguration. Timothy Jones follows this lead by undertaking a study of the major changes in gender politics in the Church of England from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. He focusses on six episodes during this period which, he claims, demonstrated the often reluctant posture of the church leaders when challenged to take a stand on matters affecting gender or sexual politics. Over the course of this hundred year span, English society evolved rapidly and adopted a much more liberal stance, which was often reflected in parliamentary debates, and found its way into progressive legislation. The result was a frequent clash of interest with the more conservative and traditional sectors of opinion, including those of the Church of England. Jones begins his survey with the debates about marriage in the mid-1850s and concludes with the heated controversies about consensual homosexuality in the 1950s. Rather than indulging in detailing the reactionary attitudes of some Church of England leaders, Jones skillfully weaves into his account the variety of positions taken over the years, and displays a commendable sympathy for most of the participants in this on-going search for new understandings amongst church members about gender and sexual politics.

Timothy Jones follows this lead by undertaking a study of the major changes in gender politics in the Church of England from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. He focusses on six episodes during this period which, he claims, demonstrated the often reluctant posture of the church leaders when challenged to take a stand on matters affecting gender or sexual politics. Over the course of this hundred year span, English society evolved rapidly and adopted a much more liberal stance, which was often reflected in parliamentary debates, and found its way into progressive legislation. The result was a frequent clash of interest with the more conservative and traditional sectors of opinion, including those of the Church of England. Jones begins his survey with the debates about marriage in the mid-1850s and concludes with the heated controversies about consensual homosexuality in the 1950s. Rather than indulging in detailing the reactionary attitudes of some Church of England leaders, Jones skillfully weaves into his account the variety of positions taken over the years, and displays a commendable sympathy for most of the participants in this on-going search for new understandings amongst church members about gender and sexual politics. The Holy Land is of course full of holy history, also of holy geography. Stuhlmann sees his job as motivating his young guests from Europe to understand the dimensions of both these features and to encourage a courageous encounter with the many history-laced dilemmas which are met in so many corners of the “promised” land. He is clearly against the kind of religious tourism which brings Christian visitors to Israel, but seeks to isolate them in the first century without ever meeting with Israel’s present-day inhabitants or their troubles. He is equally opposed to the kind of narrow eschatological proclamation of certain Christian groups, especially some American evangelicals, or to the equally one-sided Jewish extremists who wage a continual battle against their Palestinian neighbours. He is grateful for the fact that he and his younger colleagues from Germany are now looked on as representatives of the “new Germany”, and that the horrors of the Holocaust, though loudly trumpeted in state-controlled media, are not attributed to the younger generation or to him personally. Likewise he is encouraged by the friendliness of the Palestinians who see these visitors from Europe as a hopeful sign that their cause is not being forgotten by the rest of the world. And he draws hope from the fact that there are many signs of confidence building between young Jews and Arabs, not least those established at Nes Ammim itself.

The Holy Land is of course full of holy history, also of holy geography. Stuhlmann sees his job as motivating his young guests from Europe to understand the dimensions of both these features and to encourage a courageous encounter with the many history-laced dilemmas which are met in so many corners of the “promised” land. He is clearly against the kind of religious tourism which brings Christian visitors to Israel, but seeks to isolate them in the first century without ever meeting with Israel’s present-day inhabitants or their troubles. He is equally opposed to the kind of narrow eschatological proclamation of certain Christian groups, especially some American evangelicals, or to the equally one-sided Jewish extremists who wage a continual battle against their Palestinian neighbours. He is grateful for the fact that he and his younger colleagues from Germany are now looked on as representatives of the “new Germany”, and that the horrors of the Holocaust, though loudly trumpeted in state-controlled media, are not attributed to the younger generation or to him personally. Likewise he is encouraged by the friendliness of the Palestinians who see these visitors from Europe as a hopeful sign that their cause is not being forgotten by the rest of the world. And he draws hope from the fact that there are many signs of confidence building between young Jews and Arabs, not least those established at Nes Ammim itself.

Anke Silomon’s introductory chapter provides biographical details about both men. Even though she relies on already published research, the author does give a survey of their careers, which will be of value to those readers not familiar with the subject. Both men were born during the reign of the last Kaiser, and their careers spanned the whole period up to and including the time of the German Democratic Republic, i.e. after 1949. This is followed by an article by Oliver Arnhold, who in 2010 published a comprehensive study of the “German Christians” as well as of the Eisenach Institute, which took the title of“The Institute for the Research and Removal of Jewish influence on German church life”. This contribution was drawn from a lecture Arnhold gave in 2014, which was subsequently included in this volume, and concentrated primarily on the ill-fated Institute. Hence unfortunately this means that his portrait of Walter Grundmann, who is supposed to be the main topic of this volume, is too condensed.

Anke Silomon’s introductory chapter provides biographical details about both men. Even though she relies on already published research, the author does give a survey of their careers, which will be of value to those readers not familiar with the subject. Both men were born during the reign of the last Kaiser, and their careers spanned the whole period up to and including the time of the German Democratic Republic, i.e. after 1949. This is followed by an article by Oliver Arnhold, who in 2010 published a comprehensive study of the “German Christians” as well as of the Eisenach Institute, which took the title of“The Institute for the Research and Removal of Jewish influence on German church life”. This contribution was drawn from a lecture Arnhold gave in 2014, which was subsequently included in this volume, and concentrated primarily on the ill-fated Institute. Hence unfortunately this means that his portrait of Walter Grundmann, who is supposed to be the main topic of this volume, is too condensed. Susan Zuccotti is an established American scholar who has written a number of studies of the Holocaust, particularly dealing with events in France and Italy. Her latest contribution provides us with a well-researched biography of a little-known French Capuchin friar, Fr. Marie-Benoît, who was to play a significant role in rescuing Jews first in Marseilles in 1942 and then in Rome in 1943-4. Although he was to live for several decades after the war, his exploits were only recorded in French and remained largely unnoticed in remote French archives. Zuccotti was able to interview him in 1988 shortly before he died, but he was clearly a reticent witness, and it has taken her another twenty-five years to piece together his full story and to explore the determining factors which led him to play such an active role in assisting the Jewish refugees and victims of Nazi tyranny. The result is a portrait of a valiant and courageous priest whose witness in the cause of Christian-Jewish relations deserves to be better known to an English-speaking audience. So we can be grateful to Zuccotti for this helpful addition to the debate about how much (or how little) was done by various sectors of the Catholic Church to assist the Jewish victims of Nazism.

Susan Zuccotti is an established American scholar who has written a number of studies of the Holocaust, particularly dealing with events in France and Italy. Her latest contribution provides us with a well-researched biography of a little-known French Capuchin friar, Fr. Marie-Benoît, who was to play a significant role in rescuing Jews first in Marseilles in 1942 and then in Rome in 1943-4. Although he was to live for several decades after the war, his exploits were only recorded in French and remained largely unnoticed in remote French archives. Zuccotti was able to interview him in 1988 shortly before he died, but he was clearly a reticent witness, and it has taken her another twenty-five years to piece together his full story and to explore the determining factors which led him to play such an active role in assisting the Jewish refugees and victims of Nazi tyranny. The result is a portrait of a valiant and courageous priest whose witness in the cause of Christian-Jewish relations deserves to be better known to an English-speaking audience. So we can be grateful to Zuccotti for this helpful addition to the debate about how much (or how little) was done by various sectors of the Catholic Church to assist the Jewish victims of Nazism. Paul O’Shea is one of the small group of Australian scholars who have become interested in the Catholic response to the traumatic events of the twentieth century, and particularly in the career of Pope Pius XII, as he sought to deal with the crises brought on by the totalitarian regimes of Europe. Like all of his predecessors, O’Shea suffers the handicap that many of the relevant documents have yet to be released from the Vatican archives, so despite his assiduous survey of Pius’ earlier life as a Vatican diplomat and later as Cardinal Secretary of State, we still have to acknowledge the tentative evaluation of all hypotheses about his war-time policies, and especially about his so-called “silence” concerning the victimization of the Jews of Europe.

Paul O’Shea is one of the small group of Australian scholars who have become interested in the Catholic response to the traumatic events of the twentieth century, and particularly in the career of Pope Pius XII, as he sought to deal with the crises brought on by the totalitarian regimes of Europe. Like all of his predecessors, O’Shea suffers the handicap that many of the relevant documents have yet to be released from the Vatican archives, so despite his assiduous survey of Pius’ earlier life as a Vatican diplomat and later as Cardinal Secretary of State, we still have to acknowledge the tentative evaluation of all hypotheses about his war-time policies, and especially about his so-called “silence” concerning the victimization of the Jews of Europe. Bennette’s book is organized in two parts. The first, consisting of five chapters, relates the familiar story of the Kulturkampf with particular attention to events that served the construction of national identity and integration. The second, more original section is composed of four thematic chapters, devoted to the examination of “significant, sustained elements in the construction of Catholic national identity” (12); these elements include gender and femininity, schools and education, and the geographies of both Germany and Europe. Based on the evidence she offers, Bennette’s conclusions are difficult to disagree with: beginning immediately after German unification, German Catholics worked actively to build a national identity, one that differed from the mainstream Protestant version of Germanness and embraced their own religious particularity. The Kulturkampf not only failed to distance Catholics from their German identity; in fact, it solidified their attachment to the new nation and convinced them that they were an integral part of it.

Bennette’s book is organized in two parts. The first, consisting of five chapters, relates the familiar story of the Kulturkampf with particular attention to events that served the construction of national identity and integration. The second, more original section is composed of four thematic chapters, devoted to the examination of “significant, sustained elements in the construction of Catholic national identity” (12); these elements include gender and femininity, schools and education, and the geographies of both Germany and Europe. Based on the evidence she offers, Bennette’s conclusions are difficult to disagree with: beginning immediately after German unification, German Catholics worked actively to build a national identity, one that differed from the mainstream Protestant version of Germanness and embraced their own religious particularity. The Kulturkampf not only failed to distance Catholics from their German identity; in fact, it solidified their attachment to the new nation and convinced them that they were an integral part of it. Philosopher Philip Hallie wrote the first study of Le Chambon in 1979, and his work continues to shape the writing of this history. Using the framework of ethics, he sought to understand “how goodness happened” in Le Chambon by evaluating the behaviour of the villagers, and attributing a special role to the Protestant pastor André Trocmé. His explanation is that this was a religious community guided by a shared conscience and the principle of non-violence, so that sheltering Jews seemed “natural and necessary.”

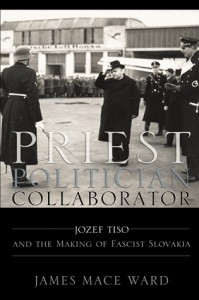

Philosopher Philip Hallie wrote the first study of Le Chambon in 1979, and his work continues to shape the writing of this history. Using the framework of ethics, he sought to understand “how goodness happened” in Le Chambon by evaluating the behaviour of the villagers, and attributing a special role to the Protestant pastor André Trocmé. His explanation is that this was a religious community guided by a shared conscience and the principle of non-violence, so that sheltering Jews seemed “natural and necessary.” When Tiso was born in 1887, Slovakia was an outlying rural part of the Hungarian kingdom, an enclave of conservative Catholicism staunchly resisting the approach of modernity, particularly in the commercial field. His education and spiritual formation as a young priest were in the highly reactionary tradition espoused by Pope Pius X. But at the same time, he welcomed the emphasis on social action, and the need for Catholics to promote a vibrant corporate life, along with engagement in corporate Catholic politics. He became the editor of a local Slovak newspaper, stressing the Catholic values of solidarity and modesty and attacking both the free-thinking Socialists and the rapacious capitalists, especially the Jews.

When Tiso was born in 1887, Slovakia was an outlying rural part of the Hungarian kingdom, an enclave of conservative Catholicism staunchly resisting the approach of modernity, particularly in the commercial field. His education and spiritual formation as a young priest were in the highly reactionary tradition espoused by Pope Pius X. But at the same time, he welcomed the emphasis on social action, and the need for Catholics to promote a vibrant corporate life, along with engagement in corporate Catholic politics. He became the editor of a local Slovak newspaper, stressing the Catholic values of solidarity and modesty and attacking both the free-thinking Socialists and the rapacious capitalists, especially the Jews. The bookend essays by senior scholars Omer Bartov and Timothy Snyder offer both critiques of current trends in the field and directions for future research. In his introductory piece, Bartov evaluates scholarly efforts of the last decade to situate the Holocaust as part of a broader phenomenon of genocidal violence in the modern world; in other words, the Final Solution is not the genocide but a genocide among others. Bartov is unsettled by attempts to compare the Holocaust to other genocides, arguing that such comparisons often obscure the particularities of the Nazi genocide and result in the erasure of the experiences of its primary victims, European Jews. Rather than understanding the Holocaust – with its enormous arsenal of scholarship and domination of popular culture – as a barrier to the study of other genocides, Bartov invites us to conceptualize it as a singular historical example of extreme violence that can in fact enrich the field of genocide studies.

The bookend essays by senior scholars Omer Bartov and Timothy Snyder offer both critiques of current trends in the field and directions for future research. In his introductory piece, Bartov evaluates scholarly efforts of the last decade to situate the Holocaust as part of a broader phenomenon of genocidal violence in the modern world; in other words, the Final Solution is not the genocide but a genocide among others. Bartov is unsettled by attempts to compare the Holocaust to other genocides, arguing that such comparisons often obscure the particularities of the Nazi genocide and result in the erasure of the experiences of its primary victims, European Jews. Rather than understanding the Holocaust – with its enormous arsenal of scholarship and domination of popular culture – as a barrier to the study of other genocides, Bartov invites us to conceptualize it as a singular historical example of extreme violence that can in fact enrich the field of genocide studies.