Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 23, Number 4 (December 2017)

Review of Mark Edward Ruff, The Battle for the Catholic Past in Germany, 1945-1980 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017). Pp. 408. ISBN 9781107190665.

Reviewed by Robert P. Ericksen

Mark Edward Ruff, Professor of History at Saint Louis University, has spent the past eleven years completing The Battle for the Catholic Past in Germany, 1945-1980. This includes four years working in Germany, supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung, the NEH, and the ACLS, as well as visits to a total of “two continents, six nations, and seventy-seven archives” (vii). The result is an important book that takes its place alongside John Connelly’s recent From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933-1965 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012). Connelly devotes more than half of his book to the period pre-1945; however, the importance of his book culminates in the 1960s, when, according to his argument, converts to Catholicism, several with German or German language roots, and especially Catholics of Jewish origin, inspired the remarkable transition in Catholic theology found in Vatican Two and Nostra Aetate.[1] Ruff’s book is more completely based in the postwar period. However, it also deals with the most salient issue addressed by postwar historians of Germany and of Catholicism: a measuring of the Catholic Church’s response to the Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler, and especially to the Shoah, the murder of six million Jews by a Christian nation within a Christian Europe. Connelly describes the incubation of ideas that led to a dramatic change in universal Catholic doctrine. Ruff describes the first thirty-five postwar years within Germany and the struggle over how to understand the history of Catholics, especially their place within and their relationship to the Nazi regime and its crimes.

Ruff begins with the assumption that both churches, Catholic and Protestant, share a compromised history within the Nazi state. He also acknowledges that both churches from 1945 to 1949 worked to polish their reputations: “Not wishing to further damage Germany’s reputation abroad …,” both Catholics and Protestants “elevated to orthodoxy the picture of the church triumphant, of clear-headed leaders valiantly resisting and the faithful unflinchingly following” (243). Not until the 1980s did historians of the Protestant Church seriously begin to redraw this rosy picture. However, Catholic behavior came under widespread attack already in the 1950s, “Doubts about the moral fitness of Catholic bishops, Cardinal Secretary of States and pontiffs of the Nazi era were cascaded before the public. They screamed from front-page headlines, the magazine covers of the most influential newsweeklies, the glossy pages of illustrated magazines and the best-seller lists in Germany and the United States.” Why did this happen? “This has been a guiding question for this book, since by almost all objective yardsticks, the German Protestant leadership left behind a more troubling record of collaboration than their Catholic counterparts” (244).[2]

Ruff begins with the assumption that both churches, Catholic and Protestant, share a compromised history within the Nazi state. He also acknowledges that both churches from 1945 to 1949 worked to polish their reputations: “Not wishing to further damage Germany’s reputation abroad …,” both Catholics and Protestants “elevated to orthodoxy the picture of the church triumphant, of clear-headed leaders valiantly resisting and the faithful unflinchingly following” (243). Not until the 1980s did historians of the Protestant Church seriously begin to redraw this rosy picture. However, Catholic behavior came under widespread attack already in the 1950s, “Doubts about the moral fitness of Catholic bishops, Cardinal Secretary of States and pontiffs of the Nazi era were cascaded before the public. They screamed from front-page headlines, the magazine covers of the most influential newsweeklies, the glossy pages of illustrated magazines and the best-seller lists in Germany and the United States.” Why did this happen? “This has been a guiding question for this book, since by almost all objective yardsticks, the German Protestant leadership left behind a more troubling record of collaboration than their Catholic counterparts” (244).[2]

Ruff clarifies early on his basic explanation of how the microscope quickly became focused on Catholics rather than Protestants in postwar Germany. First it has to do with demographics. Catholics had been an embattled minority in Germany since the aggressive Protestant, Otto von Bismarck, founded modern Germany. After 1945, millions of German Protestants were left behind in Poland and in the Soviet Union, but especially in the Russian Zone of Occupation that became East Germany. As a result, the percentage of Catholics rose from just over one-third in all of Germany prior to the war to 45 percent in postwar West Germany.

More importantly, Konrad Adenauer and his newly-created Christian Democratic Union—primarily a Catholic party, even though it invited Protestant participation—dominated the early years of West Germany, from the creation of the Federal Republic in 1949 until 1969. Ruff concludes (as “the central finding of this book”) that “controversies over the church’s relationship to National Socialism were frequently surrogates for a larger set of conflicts over how the church was to position itself in modern society—in politics, international relations, the media and the public sphere” (2). Because Catholics were powerful in the first two decades of the Federal Republic, questionable Catholic behavior under Hitler came under close inspection, an attractive target for any opponent of the Adenauer agenda. Protestants, by contrast, not exercising national power, were able to nurture their misleading claim that the Confessing Church had represented the Protestant stance in the Third Reich, and that it had been a church of resistance.

Ruff compresses the massive volume of postwar debates surrounding Catholic behavior in the Nazi era into seven chapters, each devoted to a specific controversy. Chapter 1 on the period 1945-1949 describes both Protestant and Catholic efforts to produce “postwar anthologies.” Each church strove in those years to prove their persecution under Nazism and their supposedly triumphant response. Ruff comments, “They knew—how could they not?—that the church had lost its decisive battles against the National Socialist juggernaut, its resistance notwithstanding” (13). Johannes Neuhäusler, author of the massive Cross and Swastika (1946), a story of Catholic suffering and resistance, personally resisted and suffered himself. He spent the last four years of the war in Dachau as a neighbor to Martin Niemoeller.[3] However, Ruff shows that Neuhäusler’s approach to writing history came “straight out of the playbook of a skilled intelligence operative. He presented evidence rife with omissions and manipulations …. In ambiguous documents that showed evidence of both support for the Nazi regime and opposition, he cut out passages professing support, leaving out the ellipses that would have indicated the cuts.” Later, a younger Catholic historian, Hans Müller, “discovered this cut-and-paste job … and publicly took the author to task” (34-35).

Chapter 2 describes a legal battle before the FRG’s Constitutional Court in 1956 that Ruff compares in significance to Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 in the United States. Ironically, however, this German case involved trying to protect the separation of students along denominational lines. The SPD-led government of Lower Saxony had written a law maintaining the option of faith-based public schools, but insisting they be interfaith rather than denominational. Adenauer and the CDU filed a lawsuit, wanting to protect the right of Catholic parents to send their children to publicly-funded Catholic schools. Unfortunately, the CDU had to base its case on the Reichskonkordat of 1933, which had guaranteed such schools. This opened a can of worms. The Reichskonkordat represented Hitler’s first foreign policy success and also a widely questioned “accomplishment” of Eugenio Pacelli and the Vatican. Furthermore, a close 1950s-look at the Reichskonkordat and its origins required also a close look at the Enabling Act of March 1933 that made the Reichskonkordat possible. This Enabling Act, which gave Hitler dictatorial power, had only happened with the support of every vote within the Catholic Center Party faction. Critics of Adenauer’s position began to see a corrupt bargain in the Reichskonkordat’s provision of denominational schools and the Catholic votes that had given Hitler his Enabling Act. They also accused Catholics in West Germany of wanting to keep one foot in the authoritarian past, rather than accept the democratic concepts of religious liberty and an open society. In a fine example of Ruff’s ability to describe complex events, he builds this chapter upon six episodes within the schools conflict, from battles under the Weimar Republic, through the writing of the Basic Law of the FRG, to the networks built up by each side during the public relations battles of the 1950s, and finally to the decision of the Constitutional Court.

The Court ruling in May 1957, handed down by a nine-person court with five Catholic members, confirmed the Reichskonkordat’s legal standing. On the other hand, in a complicated balancing act, it also confirmed the right of Lower Saxony to order its own school affairs, since the Basic Law of the FRG had handed all control of education to the states. Ruff notes that this climactic event in the mid-1950s set the battle lines among church historians for years to come, especially the tendency to focus on Catholic rather than Protestant behavior in Nazi Germany. It also hardened political stances, with Catholics and their allies defending the past, including the authoritarian and (to outside eyes, at least) intolerant nature of Catholic hierarchy. On the other hand, critics hardened their stance in favor of a more extensive (and increasingly secular) view of civil society, civil rights, and religious liberty.

Chapter 3 takes us into the 1960s, with a dramatic February 1961 article by Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde, “German Catholicism in 1933: A Critical Examination.” Ruff describes this as “a bolt of lightning,” given Böckenörde’s “array of devastating quotations from cardinals, bishops, theology professors and lay presidents” in support of the Nazi state (86). The young Böckenförde, a conscientious Catholic headed for an impressive career in constitutional law, inspired other members of the “1945 generation” to undertake a rigorous inquiry into the stance of those Catholic leaders. This also inspired opponents of Böckenförde’s critique to organize, including their creation of the Association for Contemporary History, a Catholic body attempting to emulate the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich and soon led by the young and “pugilistic” Catholic historian, Konrad Repgen (116-19).

Two American scholars entered the fray at about this time, first the young sociologist, Gordon Zahn, a professor at Loyola University in Chicago. Zahn spent the academic year 1956-57 in Germany, supported by a Fulbright grant. This placed Zahn in Germany just as the quarrel over denominational schools reached the Constitutional Court and grabbed his attention. Also, as a long-time member of the Catholic peace movement, he chose to interview former Catholic peace advocates in Germany during the Nazi era. In September 1959 he delivered a paper on this topic at a meeting of the American Catholic Sociological Association. In the published version, “The Catholic Press and the National Cause,” he showed how newspapers and journals had preached a hyper-nationalism that, in his view, represented a “critical failure” in their message to German Catholics. Catholics in late-1950s Germany, from Johannes Neuhäusler to the German bishops, reacted angrily to this article, as did the Vatican and the German Foreign Office. These opponents successfully barred Zahn’s ability to publish in Catholic venues, though they failed in their attempt to get Loyola University to violate his tenure rights and release him. Ruff says, however, that they made his life at Loyola “perfectly miserable” until he moved to the University of Massachusetts Boston in 1966. Despite powerful efforts to block Zahn’s impact, he got his book, German Catholics and Hitler’s Wars, into print in 1962, with a German translation in 1965 (143-46). He also inspired the next American thorn in the flesh of the German Catholic Church.

Guenter Lewy, born into a Jewish family in Breslau in 1923, fled Germany with his family, spent some time on a Palestinian kibbutz, and became part of the Jewish Brigade in the British Army. This gave him a chance to shout—in German—while his unit was taking their first German prisoners, “Surrender, the Jews are here!” (195) There is no record that he gave the same warning when he published The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany in 1964. However, the books by Zahn and Lewy in 1962 and 1964 were outside entrants into a field of criticism that raised alarms among defenders of the church in Germany. Among other things, church officials and archivists decided never again to give outsiders easy access to the sort of documents used by Zahn and Lewy, as Ruff highlights in his title to Chapter 6, “Guenter Lewy and the Battle for Sources.”

The most famous of all the early 1960s battles involved Rolf Hochhuth and his play, The Deputy, first performed in 1963. We all know this to be an early entry into the “Pius Wars,” with its condemnation of the pontiff’s alleged silence in the face of the Holocaust. Ruff gives a useful background on Hochhuth, the original production of the play, and the bitter conflicts that ensued. He concludes that “counter-strikes by the defenders of the beleaguered pontiff transformed a debate about the silence of the wartime pope into something more injurious to their cause. This was a debate about freedom of expression, civil liberties and tolerance, when in the early to mid-1960s societal attitudes on these subjects were fundamentally shifting” (156). In fact, Ruff says controversy about The Deputy “marked the fundamental turning point in the battles for the Catholic past. It represented the last gasp of the Catholic milieu, the final extraordinary mobilization of organizations, politicians and clerics. But this time it was unable to prevent a fundamental taboo from being not just infringed but shattered” (192).

Chapter 7 brings us into the 1970s and 1980s, with two powerful antagonists, Klaus Scholder and Konrad Repgen, squaring off against each other. They did so in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, in their scholarly publications, and with assistance from their graduate students. Scholder, in Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich, Band 1 (Frankfurt, 1977), did begin to see weaknesses in the Protestant response to the Nazi takeover in 1933. However, he also attempted to write about the Catholic Church, and, in his opening salvo, an article in the FAZ, he resuscitated what he had to admit was a speculative claim about linkage between Catholic Center Party votes for the Enabling Act and Hitler’s decision to negotiate a Reichskonkordat. This article, a sort of advertisement for his forthcoming book, “focused exclusively on the ignominious role played by Catholic politicians and ecclesiastical leaders in the catastrophe of 1933. Nowhere was the Protestant past from 1933 to be found in either headline or article” (226). Repgen, leader of the Association for Contemporary History of the Catholic Church, responded with vigor and tenacity, leading to a set of exchanges from 1977 to 1979. In those years Scholder, a professor of church history at Tübingen had several advantages. These included his strong political contacts to the FDP, his easy access to the press, and his role as a frequent commentator on television.

Even if Adenauer and the Catholic CDU dominated the first twenty years of the Federal Republic and even if Catholics represented 45 percent of the population, certain advantages fell not just to Scholder but to Protestants in general throughout the period from 1945 to 1980. This included the fact that Protestant behavior in Nazi Germany did not yet fall under close inspection, as did Catholic behavior. It included advantages such as that which Scholder enjoyed in his relationship to German media and the German establishment in his conflict with Repgen, despite Repgen’s ability to identify weak areas in Scholder’s arguments. It is also possible to gain from this very fine book by Mark Ruff the sense that first-generation defenders of the Catholic Church in Germany had to struggle not just with the past, but also with the future.

When Böckenförde or Hochhuth or even Klaus Scholder seemed to prevail in the court of public opinion, it had a great deal to do with the path toward our modern world and the way in which democratic ideals of religious liberty and an open society came to prevail. Mark Ruff’s well researched, well written, and cogently argued book adds significantly to our understanding of how early postwar views of churches in Nazi Germany developed. First for Catholics and eventually for Protestants, this topic moved past a struggle to defend church behaviors into an effort to understand and to learn from them. Mark Ruff makes a fine contribution in that undertaking.

[1] For my take on the remarkable nature of Nostra Aetate, see Robert P. Ericksen, “Jews and ‘God the Father’ after Auschwitz: American Responses to Nostra Aetate,” Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, 29/2 (2016), 323-36.

[2] In support of this claim, Ruff cites Manfred Gailus, “Keine gute Performance. Die deutsche Protestanten im ‘Dritten Reich,’” in Manfred Gailus and Armin Nolzen, eds., Zerstrittene “Volksgemeinschaft.” Glaube, Confession, und Religion im Nationalsozialismus (Göttingen: Vandenhoek & Ruprecht, 2011), 96-121.

[3] Neuhäeusler also participated in the famous June 5, 1945 Naples interview in which Niemoeller admitted he had been ready to fight for Germany during the war. He, Neuhäeusler, and Josef Müller all agreed that Germany was not ready for democracy, adding to the very critical press response to this interview in the West.

Lorenz’s goal is to compare New Testament passages from The Message of God with the Luther Bible, the standard translation, and the original Greek text. For this purpose, Lorenz has chosen three central terms by means of which she tries to analyze the new interpretation in The Message of God. Chapter 2 deals with the Messiah concept and the relationship between Jesus and Judaism. Chapter 3 places the concept of sacrifice at the heart of the comparison. Chapter 4 deals with the portrayal of Jesus in the New Testament traditions in comparison with Jesus’ presentation in The Message of God. The focus on concepts rather than merely on individual passages is very welcome, since, for example, in dealing with the Messiah concept, the entire Christology of The Message of God and thus of the German Christians can be derived, as Lorenz rightly states (83).

Lorenz’s goal is to compare New Testament passages from The Message of God with the Luther Bible, the standard translation, and the original Greek text. For this purpose, Lorenz has chosen three central terms by means of which she tries to analyze the new interpretation in The Message of God. Chapter 2 deals with the Messiah concept and the relationship between Jesus and Judaism. Chapter 3 places the concept of sacrifice at the heart of the comparison. Chapter 4 deals with the portrayal of Jesus in the New Testament traditions in comparison with Jesus’ presentation in The Message of God. The focus on concepts rather than merely on individual passages is very welcome, since, for example, in dealing with the Messiah concept, the entire Christology of The Message of God and thus of the German Christians can be derived, as Lorenz rightly states (83).

Studdert Kennedy, or ‘Woodbine Willie’, as he was affectionately known by soldiers, has long been the most well-known of the British wartime chaplains. He has attracted the attention of scholars of various kinds for his poetry (The Unutterable Beauty, published in 1927, remains much admired in some quarters), his trenchant criticisms of the status quo, his uncompromising socialism, his pungent scepticism of authority (one of his books was simply called Lies), and his determination that the ghastliness of war must surely and eventually yield a better world. But he was also the embodiment of courage and unselfconscious sacrifice (he won the Military Cross) and his early death, exhausted, at the age of 45, presented something of the quality of a martyrdom—not so much to the powers of the age but perhaps to the whole age in which he lived. Westminster Abbey notoriously turned down the idea of hosting his funeral. One suspects that Studdert Kennedy would have been delighted by the compliment.

Studdert Kennedy, or ‘Woodbine Willie’, as he was affectionately known by soldiers, has long been the most well-known of the British wartime chaplains. He has attracted the attention of scholars of various kinds for his poetry (The Unutterable Beauty, published in 1927, remains much admired in some quarters), his trenchant criticisms of the status quo, his uncompromising socialism, his pungent scepticism of authority (one of his books was simply called Lies), and his determination that the ghastliness of war must surely and eventually yield a better world. But he was also the embodiment of courage and unselfconscious sacrifice (he won the Military Cross) and his early death, exhausted, at the age of 45, presented something of the quality of a martyrdom—not so much to the powers of the age but perhaps to the whole age in which he lived. Westminster Abbey notoriously turned down the idea of hosting his funeral. One suspects that Studdert Kennedy would have been delighted by the compliment. In his chapter “Protestantism in Nazi Germany: A View from the Margins,” Christopher Probst draws on church sources (newsletters, conference papers, ecclesiastical correspondence, and published works) to consider how Protestants responded to the Nazi regime and living in Nazi Germany produced profound religious divisions among Protestants. Probst begins with the issue of antisemitism, noting that “many, perhaps most, German Protestant ministers and theologians had decidedly deprecating views of Jews and Judaism,” and that most were “deeply nationalistic” (244/357). He goes on to ask three main questions: “What tack did Protestant pastors and theologians take towards the Nazi regime? How did the pressures and strictures of living in the Nazi state help to fracture the Protestant church into competing factions with distinct views on myriad issues? How did Protestant clergy and theologians confront the so-called ‘Jewish Question’?” (244/357)

In his chapter “Protestantism in Nazi Germany: A View from the Margins,” Christopher Probst draws on church sources (newsletters, conference papers, ecclesiastical correspondence, and published works) to consider how Protestants responded to the Nazi regime and living in Nazi Germany produced profound religious divisions among Protestants. Probst begins with the issue of antisemitism, noting that “many, perhaps most, German Protestant ministers and theologians had decidedly deprecating views of Jews and Judaism,” and that most were “deeply nationalistic” (244/357). He goes on to ask three main questions: “What tack did Protestant pastors and theologians take towards the Nazi regime? How did the pressures and strictures of living in the Nazi state help to fracture the Protestant church into competing factions with distinct views on myriad issues? How did Protestant clergy and theologians confront the so-called ‘Jewish Question’?” (244/357)

Ruff begins with the assumption that both churches, Catholic and Protestant, share a compromised history within the Nazi state. He also acknowledges that both churches from 1945 to 1949 worked to polish their reputations: “Not wishing to further damage Germany’s reputation abroad …,” both Catholics and Protestants “elevated to orthodoxy the picture of the church triumphant, of clear-headed leaders valiantly resisting and the faithful unflinchingly following” (243). Not until the 1980s did historians of the Protestant Church seriously begin to redraw this rosy picture. However, Catholic behavior came under widespread attack already in the 1950s, “Doubts about the moral fitness of Catholic bishops, Cardinal Secretary of States and pontiffs of the Nazi era were cascaded before the public. They screamed from front-page headlines, the magazine covers of the most influential newsweeklies, the glossy pages of illustrated magazines and the best-seller lists in Germany and the United States.” Why did this happen? “This has been a guiding question for this book, since by almost all objective yardsticks, the German Protestant leadership left behind a more troubling record of collaboration than their Catholic counterparts” (244).

Ruff begins with the assumption that both churches, Catholic and Protestant, share a compromised history within the Nazi state. He also acknowledges that both churches from 1945 to 1949 worked to polish their reputations: “Not wishing to further damage Germany’s reputation abroad …,” both Catholics and Protestants “elevated to orthodoxy the picture of the church triumphant, of clear-headed leaders valiantly resisting and the faithful unflinchingly following” (243). Not until the 1980s did historians of the Protestant Church seriously begin to redraw this rosy picture. However, Catholic behavior came under widespread attack already in the 1950s, “Doubts about the moral fitness of Catholic bishops, Cardinal Secretary of States and pontiffs of the Nazi era were cascaded before the public. They screamed from front-page headlines, the magazine covers of the most influential newsweeklies, the glossy pages of illustrated magazines and the best-seller lists in Germany and the United States.” Why did this happen? “This has been a guiding question for this book, since by almost all objective yardsticks, the German Protestant leadership left behind a more troubling record of collaboration than their Catholic counterparts” (244). The book begins with two chapters offering broad surveys of early twentieth-century European culture and German war theology, respectively. Elmar Salmann’s “Der Geist der Avantgarde und der Große Krieg” covers familiar territory as it catalogs challenging and unsettling developments in modern psychology, philosophy, art, music, literature, and the natural sciences. For those contemporaries in despair over the complexity and contradictions of modern life, the Great War was a great simplifier and a welcome relief. Wolf-Friedrich Schäufele’s “Der ‘Deutsche Gott’” follows up with an overview of German war theology—also familiar terrain—but Schäufele generates new insights through his side-by-side analysis of Catholic and Protestant war theologies, his recognition of diverse perspectives among theologians of the same confession, and his cost-benefit analysis of contextual theology. In addition to those theologians of both confessions who saw the war as justified self-defense, an occasion for moral and spiritual renewal, or an experience of the sacred, Schäufele draws our attention to Protestant theologians like Reinhold Seeberg and Ferdinand Kattenbusch who believed war was a means by which God tested the ‘Geschichtsfähigkeit’ of nations, a theme that comes up again in Justus Bernhard’s chapter on Emanuel Hirsch (“’Krieg, du bist von Gott’”). Though most German war theology promoted the “civil-religious ideology of German nationalism” (73), Schäufele does not accept Karl Barth’s demand for a radical separation of theology from religious experience. As an alternative, he points to the more nuanced and critical theological engagement with wartime realities that he finds in the works of Rudolf Otto, Karl Holl, Friedrich Niebergall, and Otto Baumgarten.

The book begins with two chapters offering broad surveys of early twentieth-century European culture and German war theology, respectively. Elmar Salmann’s “Der Geist der Avantgarde und der Große Krieg” covers familiar territory as it catalogs challenging and unsettling developments in modern psychology, philosophy, art, music, literature, and the natural sciences. For those contemporaries in despair over the complexity and contradictions of modern life, the Great War was a great simplifier and a welcome relief. Wolf-Friedrich Schäufele’s “Der ‘Deutsche Gott’” follows up with an overview of German war theology—also familiar terrain—but Schäufele generates new insights through his side-by-side analysis of Catholic and Protestant war theologies, his recognition of diverse perspectives among theologians of the same confession, and his cost-benefit analysis of contextual theology. In addition to those theologians of both confessions who saw the war as justified self-defense, an occasion for moral and spiritual renewal, or an experience of the sacred, Schäufele draws our attention to Protestant theologians like Reinhold Seeberg and Ferdinand Kattenbusch who believed war was a means by which God tested the ‘Geschichtsfähigkeit’ of nations, a theme that comes up again in Justus Bernhard’s chapter on Emanuel Hirsch (“’Krieg, du bist von Gott’”). Though most German war theology promoted the “civil-religious ideology of German nationalism” (73), Schäufele does not accept Karl Barth’s demand for a radical separation of theology from religious experience. As an alternative, he points to the more nuanced and critical theological engagement with wartime realities that he finds in the works of Rudolf Otto, Karl Holl, Friedrich Niebergall, and Otto Baumgarten. Despite the initial impression that the author’s ecclesiastical position and the book’s subtitle might suggest, Baptists, Jews, and the Holocaust is no simple glorification of Baptist-Jewish history. Rather, it is a thoroughly researched analysis of diverse Baptist responses to the plight of Jews during the Nazi era. Spitzer’s sources include a wide array of archival material: annual convention or conference books of Northern, Southern, Swedish, Regular, African American, and Seventh Day Baptists; minutes and correspondence from the Baptist World Alliance; papers from various Baptist boards, societies, and personnel; and several dozen national and regional Baptist periodicals. This is complemented by three main Jewish sources—The Jewish Chronicle, The American Hebrew, and The American Jewish Yearbook—and a solid collection of relevant secondary sources. Surveying the existing accounts of scholars like William E. Nawyn, E. Earl Joiner, and Robert W. Ross, Spitzer finds only brief, negative assessments of the two large, national, and white Baptist conventions. Omitted are the African American and the regional, state, and local facets of the history.

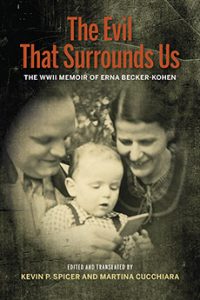

Despite the initial impression that the author’s ecclesiastical position and the book’s subtitle might suggest, Baptists, Jews, and the Holocaust is no simple glorification of Baptist-Jewish history. Rather, it is a thoroughly researched analysis of diverse Baptist responses to the plight of Jews during the Nazi era. Spitzer’s sources include a wide array of archival material: annual convention or conference books of Northern, Southern, Swedish, Regular, African American, and Seventh Day Baptists; minutes and correspondence from the Baptist World Alliance; papers from various Baptist boards, societies, and personnel; and several dozen national and regional Baptist periodicals. This is complemented by three main Jewish sources—The Jewish Chronicle, The American Hebrew, and The American Jewish Yearbook—and a solid collection of relevant secondary sources. Surveying the existing accounts of scholars like William E. Nawyn, E. Earl Joiner, and Robert W. Ross, Spitzer finds only brief, negative assessments of the two large, national, and white Baptist conventions. Omitted are the African American and the regional, state, and local facets of the history. Erna’s first entry at Christmas 1937 begins with an announcement: she and her Catholic husband, Gustav, are expecting their first child in March. By this time, Hitler had been in power in Germany for four years. Erna and Gustav had married in 1931 while Erna was still Jewish and Gustav Catholic. As Spicer and Cucchiara note, the newlyweds could have had no idea then that their religious heritages would come to matter so very much to the outside world. In the early phases of Hitler’s chancellorship, Gustav continued working in an engineering company. His status as a pure Aryan accorded Erna a measure of protection. However, as the years of the Third Reich continued, Gustav and Erna would come to see that the so-called “privileged” status of their union was really no protection against an increasingly hostile German society. What adds yet another layer to this fascinating story is that Erna had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1936. She longed for community in the face of such social isolation and persecution and she took increasing solace in her Catholic faith.

Erna’s first entry at Christmas 1937 begins with an announcement: she and her Catholic husband, Gustav, are expecting their first child in March. By this time, Hitler had been in power in Germany for four years. Erna and Gustav had married in 1931 while Erna was still Jewish and Gustav Catholic. As Spicer and Cucchiara note, the newlyweds could have had no idea then that their religious heritages would come to matter so very much to the outside world. In the early phases of Hitler’s chancellorship, Gustav continued working in an engineering company. His status as a pure Aryan accorded Erna a measure of protection. However, as the years of the Third Reich continued, Gustav and Erna would come to see that the so-called “privileged” status of their union was really no protection against an increasingly hostile German society. What adds yet another layer to this fascinating story is that Erna had converted to Roman Catholicism in 1936. She longed for community in the face of such social isolation and persecution and she took increasing solace in her Catholic faith.