Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 22, Number 3 (September 2016)

Review of Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the Nazi War of Annihilation (Harvard University Press, 2015), Pp. 352, ISBN: 9780674598485.

By Robert Ventresca, King’s University College at Western University

Lauren Faulkner Rossi has produced a measured and original contribution to the serious body of scholarship that has emerged over the past decade or so chronicling the varied responses and experiences of German Catholic priests under Nazism and in the Second World War. Actually, this book is about both ordained clergy and seminarians, an crucial distinction that merits a more precise articulation at the outset of this important study. We are talking here about a subject group that has received comparatively little attention from scholars to date: Catholic priests and seminarians who were conscripted into the Wehrmacht during the Second World War. Significantly, only a fraction of them served officially as military chaplains; this is yet another important fact that is easily overlooked given the book’s understandable emphasis on chaplains and bishops. To be clear, the subject group under study was relatively small. Of the over 17,000,000 Wehrmacht soldiers who served in the war, 17,000 self-identified as priests or seminarians–roughly one-tenth of one percent. As Faulkner Rossi openly acknowledges, both the size of the subject group as well as the limited source base from which she draws do limit the book’s analytical scope. Most of the quantitative evidence presented here is based on the records of a single seminary in Bavaria. Further qualitative and narrative analysis is drawn heavily from the recollections of one man, Georg Werthmann, the Catholic Field Vicar-General and second-in-command to Reich Catholic Field Bishop Franz Justus Rarkowski. Accordingly, Faulkner Rossi wisely sets out forthrightly the delimitations of her analysis, inviting readers to appreciate instead the rich insights that can be gleaned through a thorough case study (2). It is indeed helpful to have at the outset a clear explanation that this is not a social history of the subject group.

Lauren Faulkner Rossi has produced a measured and original contribution to the serious body of scholarship that has emerged over the past decade or so chronicling the varied responses and experiences of German Catholic priests under Nazism and in the Second World War. Actually, this book is about both ordained clergy and seminarians, an crucial distinction that merits a more precise articulation at the outset of this important study. We are talking here about a subject group that has received comparatively little attention from scholars to date: Catholic priests and seminarians who were conscripted into the Wehrmacht during the Second World War. Significantly, only a fraction of them served officially as military chaplains; this is yet another important fact that is easily overlooked given the book’s understandable emphasis on chaplains and bishops. To be clear, the subject group under study was relatively small. Of the over 17,000,000 Wehrmacht soldiers who served in the war, 17,000 self-identified as priests or seminarians–roughly one-tenth of one percent. As Faulkner Rossi openly acknowledges, both the size of the subject group as well as the limited source base from which she draws do limit the book’s analytical scope. Most of the quantitative evidence presented here is based on the records of a single seminary in Bavaria. Further qualitative and narrative analysis is drawn heavily from the recollections of one man, Georg Werthmann, the Catholic Field Vicar-General and second-in-command to Reich Catholic Field Bishop Franz Justus Rarkowski. Accordingly, Faulkner Rossi wisely sets out forthrightly the delimitations of her analysis, inviting readers to appreciate instead the rich insights that can be gleaned through a thorough case study (2). It is indeed helpful to have at the outset a clear explanation that this is not a social history of the subject group.

These delimitations are purposeful and instructive and underscore the utility of the case study approach. That priests and seminarians should comprise such a small fraction of the Wehrmacht is not at all surprising. So the question of numbers is largely irrelevant. What matters from the standpoint of historical understanding is that these priests and seminarians were conscripted in the first place and, most important of all, that they chose to serve in such overwhelming numbers; it is remarkable and telling indeed that of those conscripted, just one–Franz Reinisch, an Austrian Pallottine priest–chose the path of conscientious objection, a choice for which he was executed. Adding to the unique perspective of the subject group are two further qualifying factors. For one, as mentioned, very few of them served as military chaplains. This meant, in short, that they were not primarily, or officially at least, responsible for the pastoral care of German Catholic soldiers, even though most of them seem to have rationalized their military service precisely in this vocational sense. Second, by virtue of the secret supplement to the 1933 Reichskonkordat between the Hitler government and the Holy See, priests and seminarians conscripted into the army were to be inducted into the medical unit or to concern themselves with the “pastoral care for the troops,” under the jurisdiction of the military bishops. This meant, in practice, that most of the men in the subject group did not take up arms in the literal sense. Instead, they provided medical service, working as assistants in field hospitals, as stretcher-bearers and so on. Serving as neither chaplains nor armed soldiers, then, these priests and seminarians were something of an anomalous group.

Precisely because they were something of an anomaly, these so-called “Wehrmacht priests” make for a fascinating case study. Why did they agree to serve? Why did only one refuse? What were their experiences like on the front lines of Hitler’s war of annihilation? How did their Catholic worldview and pastoral training influence their responses to what they witnessed and their relationship with their fellow soldiers? How did the Wehrmacht priests come to terms with their participation in the war, and how did they rationalize their role in the light of their faith and their national loyalties? Faulkner Rossi does an admirable job of focussing the reader’s attention on these animating questions. Most important, she provides compelling answers that tell us much about the challenges German Catholics confronted in the face of an “ever-shifting, fluid negotiation of national and religious identity under the Nazi regime” (5). Because it was ever-shifting and fluid, that process of negotiation was ongoing. Invariably, it pushed these Wehrmacht priests onto a kind of ethical gray zone, trying to do go some good–or so they believed–while cooperating with the Hitler state in a war that many of them believed to be unjust. And yet they justified their service nonetheless, ostensibly in the name of serving God and country.

Since she wants to understand her subjects as men of their time, Faulkner Rossi offers a nuanced assessment of how these priests and seminarians reasoned and acted within the confines of their worldview. The book is perhaps most incisive and most effective at re-creating the “mental horizons”–to borrow from John Connelly–of this distinctive group of devout German Catholics who heeded the call for military service (3). It was a worldview framed by the reigning Catholic moral theology of the day, by the particular contours of their clerical training, and by their personal experiences as young German Catholics whose formative years were defined by the turbulent collapse of the Weimar Republic, the rise of Nazism and the inexorable radicalization and racialization of German society under the auspices of Gleichschaltung (16). Theirs was a German Catholic cultural and moral universe that nurtured a strong and resilient autonomous youth movement and associational life, but also learned to accommodate if not make peace entirely with the Hitler regime. This limited degree of autonomy, which lessened over time, nonetheless did create some space for German Catholics to distance themselves from certain Nazi policies and practices without feeling compelled to engage in active or even passive forms of resistance to the regime before or during the war.

Faulkner Rossi very deftly dissects these mental horizons, revealing the complex intersection and interaction of religious faith, cultural identity and national loyalty. She reasons that two themes were formative in the motivation and rationalization of conscripted priests and seminarians: the twin emotional and intellectual demands of faith and national identity (3). Faulkner Rossi concludes that most of these conscripted priests and seminarians did not go to war because they supported Nazism (154). To the contrary, she says, they “consistently divorced” their participation in the war and even the army itself–leaders and soldiers–from Nazism (154). We are told simply that most of them went to war for “a variety of reasons” (154). Two reasons appear to have been paramount: a sense of duty to care spiritually for German Catholic soldiers, and a sense of patriotic duty to defend their country. As Faulkner Rossi concludes, for the Wehrmacht priests and seminarians, “religion and nationalism worked in tandem as motivation” (154).

Importantly, this mutually reinforcing motivation produced what Faulkner Rossi evocatively describes as a “dangerous myopia,” wherein the presumed salvation of the souls of German Catholic soldiers counted above anything and everything else. In other words, an understandable pastoral impulse to care for the spiritual and emotional health of German Catholic soldiers fighting a war of annihilation proved a more powerful claim for this select group of priests and seminarians than resisting inhumane and unjust behaviour in war (155). This, according to Faulkner Rossi, is what made the Wehrmacht priests so genuinely different from other conscripts, that is, this avowedly “vocational aspect of their military service” (240). These men believed fervently that serving dutifully in the Wehrmacht meant serving God and country, not Hitler per se; they told themselves during and after the war that there was a “greater good” to be served in offering pastoral care for Catholic soldiers and mitigating the suffering of all German soldiers through other forms of compassionate service. They were determined, in Faulkner Rossi’s words, “to do some good or to make a difference for the soldiers” (154).

The logic of the “greater good” thereby provided the Wehrmacht priests with a confirmatory moral justification for serving. In short, these priests and seminarians brought to the war zone a unique blend of “training, faith, and feeling” that distinguished them from laymen soldiers and also sustained them in their military service; Faulkner Rossi labels this as a kind of “spiritual opportunism” (154). In the end, this vocational sense of military service helped the Wehrmacht priests to “rationalize their complicity with a racist, murderous regime” (155). True, these men saw their spiritual sustenance of laymen soldiers as pastorally and morally vital, and proper to their vocation and training. But this trapped them in what Faulkner Rossi rightly describes as a “flawed rationalization” (155). They told themselves that they were working for God and country and there is no reason to doubt the sincerity of that conviction, however myopic or flawed we may judge the rationalization. In the words of one former priest-soldier, identified only as Wilhelm W.

I served the Church. A side effect of this was, in effect, to render a service to the state, but I had to hazard the consequences. I believe fundamentally in helping soldiers, in serving them, in preserving the Church and to that final end serving the glory of God… The other part of it included a cooperation that one simply couldn’t repudiate (250).

Evidently, the impulse to “do some good” and to seek the “greater good” through a vocational sense of military service did not extend to speaking or acting on behalf of the innocent victims of Hitler’s wars. Paradoxically, the deeper the religious and pastoral commitment to the spiritual welfare of soldiers, the more myopic–perhaps even blinded–the Wehrmacht priests grew vis-à-vis the most vulnerable–those, as Faulkner Rossi puts it, “most in need of defense, namely Europe’s Jews” (156).

An important caveat is in order here. Much of what we know about how Wehrmacht priests rationalized their decision to serve in a war that was, as Faulkner Rossi notes, “criminal” and “antithetical” to their Catholic values, comes from written testimony some 140 priest-veterans provided many decades after the war ended. Allowing for the usual hazards of private and public memory of traumatic episodes, the reader is struck, as Faulkner Rossi was, by the obvious difficulty these priests and seminarians had in coming to terms with their service. It is impossible to ignore the fact that few of these men engaged in a serious, self-critical examination of conscience about what they saw and did or did not do on behalf of the victims during their military service.

Troublingly, most of the men claimed never to have witnessed first hand or even to have known about the atrocities until after the war, a claim that strains the limits of credulity. Consider the recollection of one Josef P., who served as a medical orderly and chaplain. He recalled being assigned to a small Polish city “full of Jews, all of whom wore the Jewish star.” But, he insisted, at that point the “systematic extermination had not yet begun…. I never witnessed atrocities against Jews or civilian populations. I only heard about it after the war.” Josef recalled hearing stories about SS troops killing Jewish children in disturbingly horrific ways. “But these were stories,” he said. “I never witnessed it. I didn’t know if it was true” (242). Still other men insisted on distinguishing and distancing the Wehrmacht from the Nazis. In the words of Kunibert P., “our Wehrmacht, or at the division I was in, was anything but Nazi…. [W]e served an unethical regime, that was clear to everyone, the Nazis were criminals…. I’ve already said, I was gladly a soldier, but we were never Nazis” (247). Of course, this exculpatory claim–we were never Nazis–was invoked widely and persistently in the years after the war by various segments of society, by powerful institutions like the military and the Church both in Germany and well beyond. In fact, Faulkner Rossi sees in the individual failure by the Wehrmacht priests to consider the consequences of their complicity with a murderous regime a corollary failure of the two institutions in which these men served–the German military and the Catholic Church (253).

To her great credit, Faulkner Rossi handles the interview responses with an appropriately critical sensitivity, thereby avoiding facile historical or moral judgements. Consequently, she is able to write persuasively about the dilemma that most of the Wehrmacht priests and seminarians faced: a binary choice between their sense of duty to offer pastoral care and sustenance to soldiers on the one hand and the inescapable realization of their complicity with a murderous regime on the other. The dilemma was captured aptly by one chaplain who said years after the war, “Naturally, one wondered repeatedly if this was a just war…. [O]n the one hand, as a Christian, one couldn’t endorse the regime, couldn’t support it. But on the other hand, we did this indirectly, by emboldening the soldiers. Doubt often came over me: should I continue doing this or not? And if I thought about the soldiers themselves, I could do nothing but continue” (251).

Such a statement conveys powerfully the sense of the inescapability of the binary choice the Wehrmacht priest and seminarians said that they faced. The irrevocable commitment to provide pastoral care for the conscience of the Catholic soldier meant that Wehrmacht priests understood and accepted that their service entailed some degree of complicity with a criminal regime. Yet, their “consciousness of the dire need for pastoral care” was the tipping point so to speak, the decisive factor in their decision to serve. Faulkner Rossi reasons that this sense of pastoral duty “outweighed any impulse to take a principled stand against a regime that did not tolerate dissent. When a priest can literally see before him a phalanx of Catholics asking for spiritual guidance in the midst of the annihilation, the idea of abandoning his training and ignoring that plea for guidance was morally irresponsible” (251).

So we are left to conclude that a moral choice lay behind the decision to serve and to do so dutifully even in the midst of the annihilation of entire communities across Eastern Europe. We know, of course, that this choice–these thousands of choices–had consequences, however unintended and unforeseen. Moreover, it remains unclear whether the choice to serve was guided primarily by religious and pastoral commitments, as we are told repeatedly in the postwar testimonials, or whether service truly was inspired and sustained by nationalism. For her part, Faulkner Rossi concludes that nationalism, not Catholicism, was the “essential ingredient” in the military service of Wehrmacht priests and seminarians. “These men,” we are told, “were deeply German” (241). If that was the case–and there is plenty of evidence presented here to substantiate the point–then the reader is left to wonder: were these Wehrmacht priests and seminarians really all that different from laymen soldiers or from Protestant chaplains and priests for that matter? More to the point, did their avowed vocational sense of military service distinguish them from laymen soldiers, or was it simply the confirmatory rationalization for serving above all to defend country–a shared goal with Nazism that clearly facilitated and eased accommodation and complicity or at the very least stifled dissent or resistance for most.

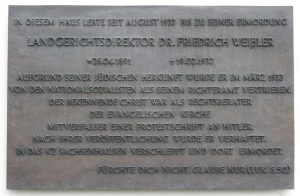

The role that these priests played in providing spiritual guidance and perhaps even forms of formal or informal absolution to soldiers waging a war of annihilation is a troubling yet deeply consequential question that warrants further research and analysis. It is deeply consequential because it cuts to the heart of the choices soldiers (and civilians) made in the midst of the Nazi war of annihilation: the choice to follow orders or to refuse; the choice to look away when confronted with brutality and violence or to protest, to dissent, to resist; the choice to refuse to be conscripted or to serve dutifully, thereby playing a part, however small or indirect, as a cog in the wheel of the machinery of destruction. It may be true that most of the Wehrmacht priests were never avowed Nazis but, as Faulkner Rossi reminds us, other people–including some priests–made other choices and paid the ultimate sacrifice for them. That is the moral of the story of conscientious objectors like Franz Reinisch, a story that is told altogether too briefly and too hurriedly at the end of this otherwise very informative book. Thanks to Lauren Faulkner Rossi, we now have a much deeper understanding of why and how priests served in Hitler’s war of annihilation. The perplexing and troubling question persists, though: why were there so few priests like Father Reinisch?

The extent and importance of religious faith in the First World War is undoubtedly one of the great rediscoveries of the centenary years. Among the belligerent empires and nations, religion proved to be a vital sustaining and motivating force, with the Ottoman war effort cloaked as a jihad, the United States entering the war on Good Friday 1917, and even professedly secular societies such as France experiencing a degree of religious revival. At the same time religious convictions also provided some of the most powerful critiques of the war, contributing to tireless peace-making efforts by Pope Benedict XV and to the stand of thousands of conscientious objectors in Great Britain and the United States. Faith also inspired many of the women who were active in war resistance and initiatives for peace, including Quakers, feminists and Christian socialists who were involved in the Hague Peace Congress of 1915, the resulting Women’s International League, and also grassroots action such as the Women’s Peace Crusade, which was launched in Glasgow in the summer of 1916.

The extent and importance of religious faith in the First World War is undoubtedly one of the great rediscoveries of the centenary years. Among the belligerent empires and nations, religion proved to be a vital sustaining and motivating force, with the Ottoman war effort cloaked as a jihad, the United States entering the war on Good Friday 1917, and even professedly secular societies such as France experiencing a degree of religious revival. At the same time religious convictions also provided some of the most powerful critiques of the war, contributing to tireless peace-making efforts by Pope Benedict XV and to the stand of thousands of conscientious objectors in Great Britain and the United States. Faith also inspired many of the women who were active in war resistance and initiatives for peace, including Quakers, feminists and Christian socialists who were involved in the Hague Peace Congress of 1915, the resulting Women’s International League, and also grassroots action such as the Women’s Peace Crusade, which was launched in Glasgow in the summer of 1916.

Anke Silomon’s introductory chapter provides biographical details about both men. Even though she relies on already published research, the author does give a survey of their careers, which will be of value to those readers not familiar with the subject. Both men were born during the reign of the last Kaiser, and their careers spanned the whole period up to and including the time of the German Democratic Republic, i.e. after 1949. This is followed by an article by Oliver Arnhold, who in 2010 published a comprehensive study of the “German Christians” as well as of the Eisenach Institute, which took the title of“The Institute for the Research and Removal of Jewish influence on German church life”. This contribution was drawn from a lecture Arnhold gave in 2014, which was subsequently included in this volume, and concentrated primarily on the ill-fated Institute. Hence unfortunately this means that his portrait of Walter Grundmann, who is supposed to be the main topic of this volume, is too condensed.

Anke Silomon’s introductory chapter provides biographical details about both men. Even though she relies on already published research, the author does give a survey of their careers, which will be of value to those readers not familiar with the subject. Both men were born during the reign of the last Kaiser, and their careers spanned the whole period up to and including the time of the German Democratic Republic, i.e. after 1949. This is followed by an article by Oliver Arnhold, who in 2010 published a comprehensive study of the “German Christians” as well as of the Eisenach Institute, which took the title of“The Institute for the Research and Removal of Jewish influence on German church life”. This contribution was drawn from a lecture Arnhold gave in 2014, which was subsequently included in this volume, and concentrated primarily on the ill-fated Institute. Hence unfortunately this means that his portrait of Walter Grundmann, who is supposed to be the main topic of this volume, is too condensed. Philosopher Philip Hallie wrote the first study of Le Chambon in 1979, and his work continues to shape the writing of this history. Using the framework of ethics, he sought to understand “how goodness happened” in Le Chambon by evaluating the behaviour of the villagers, and attributing a special role to the Protestant pastor André Trocmé. His explanation is that this was a religious community guided by a shared conscience and the principle of non-violence, so that sheltering Jews seemed “natural and necessary.”

Philosopher Philip Hallie wrote the first study of Le Chambon in 1979, and his work continues to shape the writing of this history. Using the framework of ethics, he sought to understand “how goodness happened” in Le Chambon by evaluating the behaviour of the villagers, and attributing a special role to the Protestant pastor André Trocmé. His explanation is that this was a religious community guided by a shared conscience and the principle of non-violence, so that sheltering Jews seemed “natural and necessary.” The bookend essays by senior scholars Omer Bartov and Timothy Snyder offer both critiques of current trends in the field and directions for future research. In his introductory piece, Bartov evaluates scholarly efforts of the last decade to situate the Holocaust as part of a broader phenomenon of genocidal violence in the modern world; in other words, the Final Solution is not the genocide but a genocide among others. Bartov is unsettled by attempts to compare the Holocaust to other genocides, arguing that such comparisons often obscure the particularities of the Nazi genocide and result in the erasure of the experiences of its primary victims, European Jews. Rather than understanding the Holocaust – with its enormous arsenal of scholarship and domination of popular culture – as a barrier to the study of other genocides, Bartov invites us to conceptualize it as a singular historical example of extreme violence that can in fact enrich the field of genocide studies.

The bookend essays by senior scholars Omer Bartov and Timothy Snyder offer both critiques of current trends in the field and directions for future research. In his introductory piece, Bartov evaluates scholarly efforts of the last decade to situate the Holocaust as part of a broader phenomenon of genocidal violence in the modern world; in other words, the Final Solution is not the genocide but a genocide among others. Bartov is unsettled by attempts to compare the Holocaust to other genocides, arguing that such comparisons often obscure the particularities of the Nazi genocide and result in the erasure of the experiences of its primary victims, European Jews. Rather than understanding the Holocaust – with its enormous arsenal of scholarship and domination of popular culture – as a barrier to the study of other genocides, Bartov invites us to conceptualize it as a singular historical example of extreme violence that can in fact enrich the field of genocide studies.

After the genocide, Cardinal Roger Etchegaray asked church leaders in Rwanda if “the blood of tribalism proved deeper than the waters of baptism”—a question that seems to speak deeply to Carney’s investigation of the role of the church. Carney quotes it both in the Introduction and the Epilogue (pp. 2, 207), though not in support of the idea of “tribalism.” On the contrary, he argues that the Hutu-Tutsi division was mobilized ideologically for defining Rwanda’s national independence from colonialism. As a historian, however, he wonders why people of the same faith ended up slaughtering each other. As a matter of fact, whereas Catholic parishes served as sanctuaries during anti-Tutsi violence in the years 1959 to 1964, this protection utterly failed in 1994, when “more Tutsi died in churches than anywhere else” (p. 197). An estimated 75,000 were slaughtered in the Kabgayi parish alone, the center of Catholic life since the early twentieth century. Throughout Rwanda, more than 200 priests and people from religious orders (mostly Tutsi) were killed, while other priests actively endorsed or supported the interahamwe militias, like diocesan priest Fr. Athanase Seromba, who burned down a church with 2,000 Tutsi inside (p. 308, n.124). How can we account for the dramatic shift from Catholic sanctuary to mortuary?

After the genocide, Cardinal Roger Etchegaray asked church leaders in Rwanda if “the blood of tribalism proved deeper than the waters of baptism”—a question that seems to speak deeply to Carney’s investigation of the role of the church. Carney quotes it both in the Introduction and the Epilogue (pp. 2, 207), though not in support of the idea of “tribalism.” On the contrary, he argues that the Hutu-Tutsi division was mobilized ideologically for defining Rwanda’s national independence from colonialism. As a historian, however, he wonders why people of the same faith ended up slaughtering each other. As a matter of fact, whereas Catholic parishes served as sanctuaries during anti-Tutsi violence in the years 1959 to 1964, this protection utterly failed in 1994, when “more Tutsi died in churches than anywhere else” (p. 197). An estimated 75,000 were slaughtered in the Kabgayi parish alone, the center of Catholic life since the early twentieth century. Throughout Rwanda, more than 200 priests and people from religious orders (mostly Tutsi) were killed, while other priests actively endorsed or supported the interahamwe militias, like diocesan priest Fr. Athanase Seromba, who burned down a church with 2,000 Tutsi inside (p. 308, n.124). How can we account for the dramatic shift from Catholic sanctuary to mortuary?