Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 19, Number 1 (March 2013)

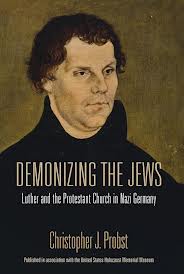

Review of Christopher J. Probst, Demonizing the Jews: Luther and the Protestant Church in Nazi Germany (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012), xiv + 251 Pp., ISBN 978-0-253-00098-9.

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University College

Christopher Probst has written an insightful analysis of the ways in which Protestant reformer Martin Luther’s anti-Jewish writings were used by German Protestants during the Third Reich. Fundamental to Probst’s work is his consistent use of Gavin Langmuir’s distinction between non-rational anti-Judaism (antipathy rooted in theological differences or other symbolic language which stand apart from and not against rational thought) and irrational antisemitism (antagonism rooted in factually untrue and slanderous accusations against Jews). In contrast to the idea that pre-modern anti-Jewish thought was generally religious and therefore anti-Judaic while modern anti-Jewish thought is political or racial and therefore antisemitic, Probst sees both anti-Judaic and antisemitic elements in the language of Luther and the twentieth-century German theologians, church leaders, and pastors who invoked him (3-4, 6, 17-19). In light of this, Demonizing the Jews is a book about historical continuity.

Christopher Probst has written an insightful analysis of the ways in which Protestant reformer Martin Luther’s anti-Jewish writings were used by German Protestants during the Third Reich. Fundamental to Probst’s work is his consistent use of Gavin Langmuir’s distinction between non-rational anti-Judaism (antipathy rooted in theological differences or other symbolic language which stand apart from and not against rational thought) and irrational antisemitism (antagonism rooted in factually untrue and slanderous accusations against Jews). In contrast to the idea that pre-modern anti-Jewish thought was generally religious and therefore anti-Judaic while modern anti-Jewish thought is political or racial and therefore antisemitic, Probst sees both anti-Judaic and antisemitic elements in the language of Luther and the twentieth-century German theologians, church leaders, and pastors who invoked him (3-4, 6, 17-19). In light of this, Demonizing the Jews is a book about historical continuity.

One of Probst’s important contributions is to show how complex and paradoxical antipathy towards Jews could be in Nazi Germany. Indeed, Demonizing the Jews begins with two snapshots from the life of Pastor Heinrich Fausel of Heimsheim, Württemberg. First, we learn that in 1934 Fausel gave a public lecture on the “Jewish Problem” in which he recycled Martin Luther’s harsh pronouncements against the Jews of his day. Then, we discover that in 1943 Fausel and his wife sheltered a Jewish woman during the Holocaust. What was it about his attitudes towards Jews, Probst wonders, that enabled him to condemn Jews as a “threatening invasion” of a “decadent” people and yet rescue one of them? (1) Was Fausel antisemitic or anti-Judaic?

More importantly, Probst asks what role Luther’s writings about Jews and Judaism might have played in the life of Fausel. More broadly, he wonders: “Was the generally anemic response to anti-Jewish Nazi policy on the part of German Protestants due at least in part to the denigration of Jews and Judaism in Luther’s writings, to a more general traditional Christian anti-Judaism, or to some other cultural, social, economic, or political factors particular to Germany in the first half of the twentieth century?” (8). Here Probst has identified an important gap in the literature, for he has found no study which has thoroughly analyzed the use of Luther’s anti-Judaic and antisemitic writings in Nazi Germany (6). This he sets out to do, employing not the classic texts of Dietrich Bonhoeffer or Karl Barth, but rather less prominent writings which he argues more completely capture the “conventional views” of German clergy (7, 19-20). No doubt many scholars will assume, with the author, that “surely many Protestants in Hitler’s Germany might have read Luther’s recommendations and sensed the congruities with the gruesome antisemitic program unfolding around them” (13).

Probst analyzes the history of German Protestant anti-Judaism and antisemitism in six well-organized chapters. And overview of Protestantism in Nazi Germany and a careful examination of Luther’s writings about Jews set the stage for his analysis of the twentieth-century appropriation of the sixteenth-century reformer’s ideas. Four chapters make up the heart of the work—one devoted to academic theologians from across the church-political spectrum and three devoted to clergy from the Confessing Church, the German Christian Movement, and the non-affiliated “middle”—the largest group within the German Protestant clergy of the Nazi era.

Overall, what Probst finds is that German Christian clergy, theologians, and church leaders “consistently embraced Luther’s irrational antisemitic rhetoric as their own, frequently pairing it with idealized portraits of ‘Teutonic’ or ‘German’ greatness, anti-Bolshevism, and anti-Enlightenment sentiment” (14). Confessing Church clergy and theologians tended to emphasize “Luther’s non-rational anti-Judaic arguments against Jews” but generally remained silent about his antisemitic outbursts and usually tried to distance themselves from the racial antisemitism of the German Christians and the Nazi state. Clergy from the middle of the church-political spectrum drew on both anti-Judaic and antisemitic aspects of Luther’s Jewish writings, often sliding into xenophobic stereotypes of Jews, such as the Jew as usurer (14).

In his opening chapter on Protestantism in Nazi Germany, Probst draws on Shulamit Volkov’s argument that antisemitism became a “cultural code” in Wilhelmine Germany, deeply embedded in society even during times when political antisemitism waned. He also highlights the importance of the ongoing publication of the Weimar edition of Luther’s Werke, including volume 53 containing On the Jews and Their Lies and On the Ineffable Name and on the Lineage of Christ, which was published in 1919. Probst also explains the importance of the “Luther Renaissance,” the revival of scholarly interest in Martin Luther which unfolded in the interwar era, noting its openness to nationalistic and antisemitic sentiments (26). As an example of the nationalistic, political, and even racial nature of German theology in the Weimar and Nazi eras, Probst assesses three works of the Erlangen theologian Paul Althaus: “The Voice of the Blood” (1932), Theology of the Orders (1934), and Völker before and after Christ (1937). What stands out here is the importance Althaus gave to the notion of the racial or blood-bound Volk as an elevated community established by God. It is in this context that Luther became important for German Protestants during the interwar era, both as national hero and (less so) as an antisemitic model (37-38).

Many readers will appreciate Probst’s careful analysis of Luther’s Judenschriften. Importantly, Demonizing the Jews strives to place Luther and his anti-Judaic and antisemitic rhetoric in proper historical context, noting the prevalence of negative stereotypes of Jews in the later Middle Ages, the frequency of accusations of host desecration leveled against Jews, the extent of anti-Jewish prejudice among church leaders (including reformers like Martin Bucer and Andreas Osiander), and the presence of important anti-Judaic and antisemitic publications, including Anthonius Margaritha’s The Whole Jewish Faith, in which a converted Jew made numerous provocative charges about his former coreligionists. Probst surveys Luther’s writings on Jews from the moderate and somewhat philosemitic That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew (1523) to the sharply anti-Judaic and crudely antisemitic On the Jews and Their Lies and On the Ineffable Name and on the Lineage of Christ (both 1543), demonstrating both the importance of Luther’s theological opposition to Judaism and the extent to which his harsher attacks were “steeped in late medieval anti-Jewish paranoia” (50). While Probst places Luther carefully in his sixteenth-century context and cautions against various simplistic interpretations of Luther’s anti-Jewish writings (early vs. late Luther, anger over the absence of Jewish conversions, declining health and increasing upset in old age), he refrains from offering a decisive explanation for Luther’s antipathy towards Jews and Judaism (51-58). What is clear is that the Luther’s antisemitic social program was ignored for over three hundred years, until it was revived in a completely decontextualized manner by Nazi propagandists and Weimar-era Protestant writers.

Turning his attention to academic theologians from both the Confessing Church and the German Christian Movement in chapter three, Probst again sets his historical discussion carefully in context, briefly explaining the politicization of German universities and academic theology in the Third Reich. Surveying four theologians—Eric Vogelsang of Königsberg University; Wolf Meyer-Erlach of Jena University; Hermann Steinlein, pastor of Ansbach; and Gerhard Schmidt of Nuremberg Seminary—the author finds that “German Christian theologians usually adopted Luther’s irrational antisemitic rhetoric as their own, often coupling it with notions that included idealized portraits of ‘Teutonic’ or ‘German’ greatness and anti-Enlightenment sentiment” (81). Confessing Church theologians tended to employ Luther’s anti-Judaic arguments only but still usually supported the Nazi state’s antisemitic program, which mirrored Luther’s own antisemitic recommendations. As Probst concludes, “We have seen here that a Confessing Church pastor, a Confessing Church theologian, and two German Christian theologians all agree that Luther was ‘correct’ to be antisemitic, or at least ‘anti-Jewish’” (82).

Chapters four through six ask how Confessing Church, German Christian, and non-aligned parish and higher clergy used Luther’s anti-Jewish writings in the course of their parish duties or church leadership. Probst returns to the subject of the opening pages of the book, Pastor Heinrich Fausel, who was in fact a member of the Confessing Church. The Heimsheim pastor espoused a relatively apolitical theology, though one marked by the theology of the orders of creation. Like so many of his colleagues from across the Reich, Fausel advocated the close connection between the German Volk and the Christian God. The resurrection of Germany “after bad times” (Probst’s words, not Fausel’s) depends on Christian devotion to God, which Probst describes, perhaps optimistically, as “explicitly scriptural and spiritual—and in no way political.” (94) Probst goes on to explain how, in the course of wartime suffering and the destruction of property, Fausel proclaimed the name of Jesus to be the source of forgiveness, healing, and victory. Statements like these, I would argue, are in fact much more political than the author suggests, given the context in which they arise.

When Fausel gave a public lecture on the Jewish Question in 1934, he refused to engage with biological notions of Jewishness but limited his discussion to the spiritual realm, where the person of Christ determined the fate of the Church, the peoples of the world, and the Jews. Fausel highlighted Jewish disobedience and stubbornness, using Isaiah 5 and its description of God’s vineyard, which Israel neglected to care for. Even as he began to discuss Jews in the New Testament, Fausel explained the “Jewish Question” as a “besetting” problem and described the “terrifying foreign invasion” of Jews since the nineteenth century as a threat Germany had to defend itself from. That said, Fausel affirmed that opposition between Jews and gentiles in the New Testament was only about Christ and not about race. Still, Israel’s rejection of Christ was, in Fausel’s words, a “unanimous rejection by an entire Volk, its leaders included,” even though (as the pastor explained) Jesus came to earth as part of the Jewish Volk (96). When Fausel discussed Luther’s views about Jews, he noted the reformer’s early positivity, but then explained how Luther dissociated himself from Jews and later unleashed his “full wrath” on them (96-97). Fausel noted how Luther saw the Jews as Christ’s enemies, how he recommended that the political authorities undertake severe measures against them, and how he lost hope for their conversion (97).

Throughout this section, Probst is careful to note that Fausel drew not only on Luther’s theological (non-rational) anti-Judaic sentiments, but also on his socio-political (irrational) antisemitic recommendations. Indeed, Fausel went on to speak approvingly of the state’s efforts to protect the German Volk from the Jews. He opposed Jewish-gentile intermarriage and supported restrictions to the number of Jewish civil servants in Germany. Though his arguments derived primarily from theology (for Probst, non-rational anti-Judaism), the practical outworking of this theology was Fausel’s approval of the distinctly antisemitic social and political measures undertaken by the Nazi state.

Most curiously (again), despite these views, Fausel and his wife later hid and cared for a Jewish woman during the Second World War, an act Probst has no real explanation for, on account of the lack of clear evidence. Rightly, he notes that people often act at variance with their stated beliefs, noting also that Fausel may have had something of a change of heart, given that he later signed the Württemberg Ecclesiastical-Theological Society’s 1946 Declaration on the Jewish Question—a frank confession of collective guilt from Protestants who realized they had been bystanders to the persecution of Jews (97-99, 171-172).

Probst agrees with Wolfgang Gerlach that even Confessing Church clergy did not support protection for Jews in Nazi Germany (113). Though he argues that they focused primarily on the biblical or theological aspects of Luther’s anti-Jewish writings, he adds that they reached “too easily for irrational and/or xenophobic reasoning in their writings and lectures” (116). If this was the case for Confessing Church clergy, Probst demonstrates that German Christian clergy were even more likely to draw on the explicitly antisemitic aspects of Luther’s writings. “The German Christian literature is overwhelmingly laden with strident attacks on Jews based on irrational conceptions about them. They are said to possess ‘fanatical hatred’ and ‘pernicious power.’ They are the ‘scum of mankind.’” Indeed, German Christians used terms like “Jewish Bolshevism” while urging the Nazi state to wage a “defensive struggle” against Jewish “Volk-disintegrating” power. Probst concludes: “Ultimately, many in the German Christian movement believed it was a matter of annihilate or be annihilated.” (142) As might be expected, non-aligned clergy from the Protestant middle landed somewhere between the Confessing Church and German Christian positions—more likely to invoke Luther’s non-rational anti-Judaic arguments against Jews but also more likely to elevate the German Volk as an order of creation and generally ready to support National Socialism and to identify Jews with Bolshevism (168-169).

One criticism of Demonizing the Jews might be its limited research base. It is to the author’s advantage that he analyzes individual anti-Jewish writings in good depth, but it is somewhat problematic to draw nuanced conclusions about the differences between Confessing Church, German Christian, and non-aligned clergy from such a small sampling of theological writings. That said, nothing I have seen in the parish archives of church districts from diverse regions of Nazi Germany would contradict Probst’s findings.

In the end, it is easy to agree with Probst’s conclusion that the anti-Judaic and antisemitic writings and lectures of German Protestant clergy “reinforced the cultural antisemitism and anti-Judaism of many Protestants in Nazi Germany” (172). Most importantly, however, by applying Langmuir’s more sophisticated definitions of anti-Judaism and antisemitism—both sentiments existed in the writings of Martin Luther and in those of his twentieth-century followers in Nazi Germany—Probst has demonstrated how deeply the continuities of anti-Jewish sentiment stretch from Nazi Germany back through the centuries to Luther and beyond. Surely there can be little question that Christian anti-Judaism and antisemitism contributed significantly to the dehumanization of the Jews, fueling the ideological fire that became the Holocaust.

The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” (

The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” ( This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.)

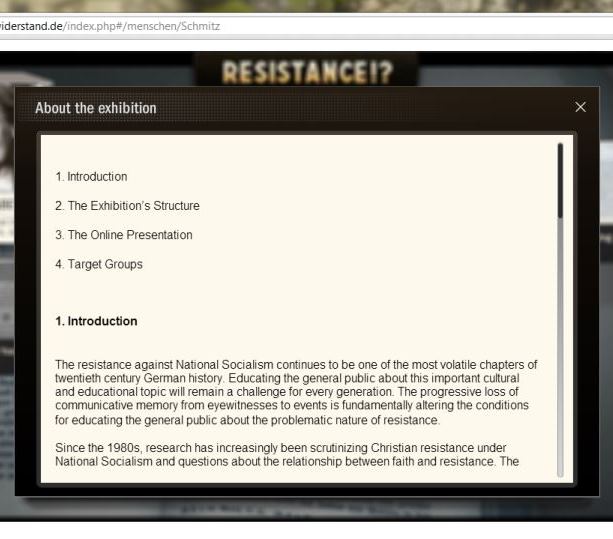

This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.) In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.”

In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.” A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship.

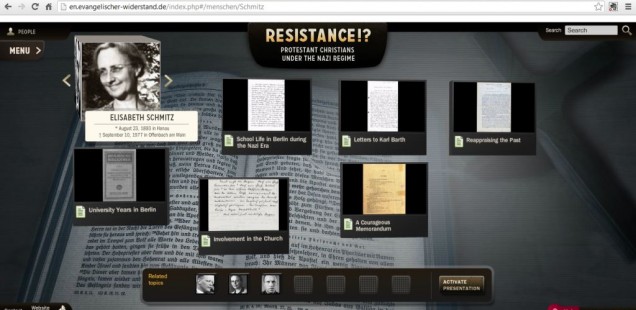

A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship. Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history

Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history  Once again this past year, the German Studies Association conference included a number of interesting panels or papers devoted to contemporary church history.

Once again this past year, the German Studies Association conference included a number of interesting panels or papers devoted to contemporary church history.