Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 19, Number 1 (March 2013)

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University College

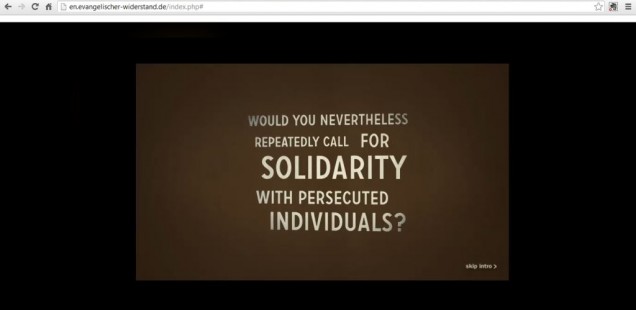

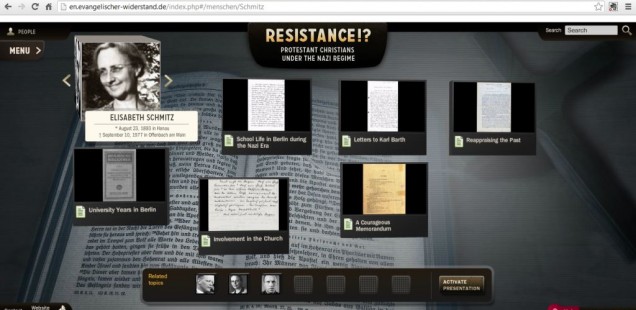

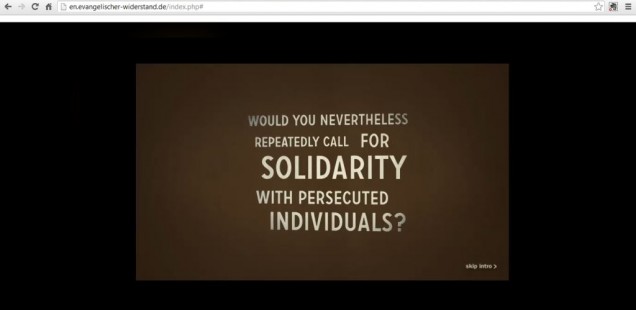

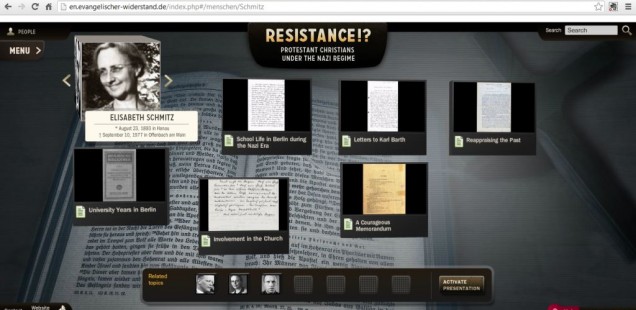

The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” (www.evangelischer-widerstand.de) is a powerful presentation of the Protestant Christian resistance to Hitler in both German and English. Automatically detecting my country of origin, the English website loaded a moving audio-visual introduction: “Imagine that your desperate exhortations go unheard. Would you nevertheless repeatedly call for solidarity with persecuted individuals?” The answer to this question is a short narration about Elisabeth Schmitz, a Berlin high school teacher who appealed to Confessing Church leaders to help Jews, wrote an important memorandum on the topic, aided persecuted Jews, and quit her teaching position in protest against the National Socialist system. Three similarly worded questions follow, on the subjects of refusing to endorse the Nazi regime, rejecting the values of the Nazi legal system, and voicing anti-war convictions during the Second World War. In turn, these questions are answered with biographical snippets about Otto and Gertrud Mörike, a pastoral couple; Martin Gauger, a Confessing Church lawyer; and Johannes Schröder, a Confessing Church military chaplain who became an anti-war activist. Bridging to the motto, “Resistance!? Protestant Christians under the Nazi Regime,” the splash page dissolves to reveal an attractive map of the Third Reich covered in icons of men and women.

The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” (www.evangelischer-widerstand.de) is a powerful presentation of the Protestant Christian resistance to Hitler in both German and English. Automatically detecting my country of origin, the English website loaded a moving audio-visual introduction: “Imagine that your desperate exhortations go unheard. Would you nevertheless repeatedly call for solidarity with persecuted individuals?” The answer to this question is a short narration about Elisabeth Schmitz, a Berlin high school teacher who appealed to Confessing Church leaders to help Jews, wrote an important memorandum on the topic, aided persecuted Jews, and quit her teaching position in protest against the National Socialist system. Three similarly worded questions follow, on the subjects of refusing to endorse the Nazi regime, rejecting the values of the Nazi legal system, and voicing anti-war convictions during the Second World War. In turn, these questions are answered with biographical snippets about Otto and Gertrud Mörike, a pastoral couple; Martin Gauger, a Confessing Church lawyer; and Johannes Schröder, a Confessing Church military chaplain who became an anti-war activist. Bridging to the motto, “Resistance!? Protestant Christians under the Nazi Regime,” the splash page dissolves to reveal an attractive map of the Third Reich covered in icons of men and women.

This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.)

This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.)

There is much to commend about “Evangelischer Widerstand.” The Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History is entirely correct in its awareness of the need to tell the story of the German churches under Hitler in new ways to new generations. This website is far more likely to reach young German Protestants than any of the excellent histories which continue to be written by scholars in Germany, Britain, North America, and elsewhere. The compelling questions posed in the introduction to the website raise fundamental moral questions and anticipate a website that presents meaningful stories of unambiguous Christian resistance to Nazism.

The inclusion of photographs, documents, and audio clips adds to the interest, and the decision to tell the story of Christian resistance largely through bite-sized biographies of famous (and not so famous) Germans is surely the most engaging approach available. Included are the expected personalities like Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Martin Niemöller, Wüttemberg Protestant Bishop Theophil Wurm, and the Kreisau Circle, along with Catholic Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen and Anglican Bishop George Bell, to provide some international and ecumenical flavour. But there are also lesser known Christians: attorney Hans Buttersack, vicar and teacher Ina Gschlössl, teacher Georg Maus, and vicar Katharina Staritz. The witness of their lives and opposition to Nazism within the ecclesiastical realm demonstrate that there were indeed members of an “other Germany” who did not bow to Hitler or abandon persecuted Jews.

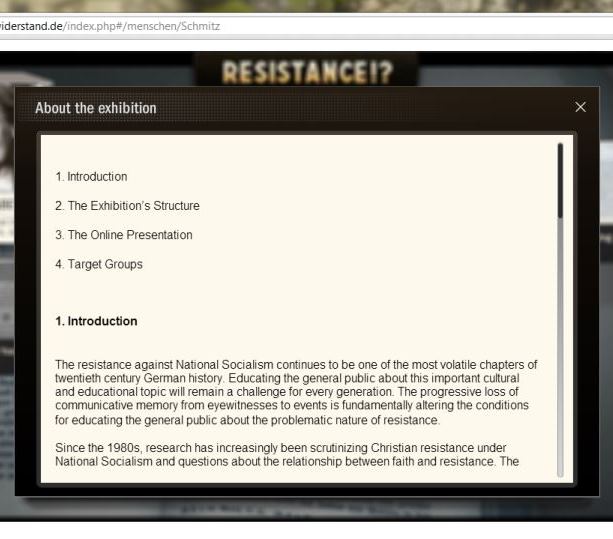

In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.”

In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.”

In response to these questions, the Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History hopes their online academic exhibition will cover “the entire range of Protestants’ resistance under the Nazi regime, including its manifestations and ambivalences.” Here the scholars behind the exhibition focus on “Christian resistance,” which they define as “resistance engendered by the Bible and bound by traditional fundamental Christian values.” And they identify several forms of resistance,

from partial discontent to disobedience and protest up through coup attempts, resistance in the narrower sense of the word. At issue was defending the Church’s right of existence and the authenticity of the Christian message from the threat of ideological dictatorship as well as defending the rule of law and human dignity in an unjust regime.

The rationale closes with the claim that “the exhibition clearly establishes that resistance motivated by Christian faith was invariably the exception among the wide range of options for Christian and ecclesiastical action in the Nazi era.”

Except that it doesn’t. Visitors to the “Evangelischer Widerstand” website are unlikely to leave with the impression that Christian resistance was the exception in the Third Reich. I have quoted extensively from “About the exhibition” because it explains two basic flaws that run right through the website: the definition of resistance and the assumption of resistance.

Concerning the definition of resistance, nowhere does the site actually define the term. This is baffling, given that historians have been debating the definition of resistance intensively since the 1970s, employing or critiquing terms like resistance, opposition, non-conformity, dissent, protest, or immunity. Throughout the English website, however, resistance is employed almost universally; opposition is used a handful of times, but non-conformity and dissent are absent. There is one article on “Everyday Protest” in which discusses “minor forms of social disobedience,” but also uses both the words “resisted” and “protest and assertion,” avoiding clarity on the issue. On the German site, Widerstand is used throughout, with Opposition, Resistenz, and Verweigerung showing up occasionally, though they are never defined. The German article equivalent to the “Everyday Protest” article is even more confusing, for the article itself is called “Verweigerung im Alltag,” but includes the words “widersetzten sich,” “sozialen Ungehorsams,” and “Nichtteilnahme.”

The result of the near-universal employment of Resistance and Widerstand is to suggest that every church protest against some specific Nazi policy or particular encroachment into the ecclesiastical realm was akin to a principled opposition to National Socialism as a movement or to a forcible attempt to overthrow the Hitler regime. The professional historical scholarship on the German churches in the Third Reich abandoned this simplistic interpretive approach decades ago. There’s no good reason why the Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History, filled with excellent scholars, should employ such an outdated interpretive concept of resistance today.

The second weakness of the website is the assumption of resistance. The treatment of individuals and topics runs from heroic resistance to compromised resistance, but never to indifference, compromise, or collaboration, which were in fact the normative responses of Christians in Nazi Germany. For instance, in the “Fundamental Questions” section of the site, the introduction begins with a window called “Action at the Margins,” which states that “Resistance in totalitarian regimes means action at the margins: The divide between (un-)lawfulness and justice, between courage and foolhardiness, between reasons of state and conscience. Christians’ resistance against National Socialism is no exception here.” The introduction moves on to discuss “Christian Resistance” within the context of a totalitarian Nazi regime, “Action in Obscurity.” Another window on “Fundamental Questions” briefly mentions that the questions of resistance are not merely about “black and white or good and evil.” After that, however, there follow several more windows on motivations for resistance, Christian and Church resistance, and denominational and ecumenical resistance.

Further along, a “Contradictions” area notes how Christian faith could also “crush the potential for resistance.” Yet even here the authors of the text do not consider indifference, compromise, or collaboration. They only note that resisters grappled with the command of Romans 13 to obey political authorities and debated “the ethical justifiability of tyrannicide.” The text continues: “This ambivalence is reflected in many biographies, even ones where faith initially made supporters of the NSDAP out of individuals who later turned their backs on National Socialism and became its opponents.” So ambivalence is present, but generally appears to have been overcome in the lives of Christian resisters. Other parts of the “Fundamental Questions” section treat issues such as Christian ethics, defense of others, consideration of consequences, gender-specific resistance, and contrasts between clergy and laity. But the net result is still a site devoted only to resistance, and not to a consideration of the wider range of responses to Nazism among Protestants—or Catholics, for that matter.

A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship.

A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship.

One might protest that the aim of “Evangelischer Widerstand” is just that—to highlight Protestant resistance. Fair enough, but when the stated goal of the Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History is to “appeal to users with different educational backgrounds and interests and of different ages” (i.e. to engage a younger, web-surfing generation) for the purpose of “educating the general public about the problematic nature of resistance,” such an unbalanced telling of the story creates a false impression on uninitiated viewers of the website. Coupled with the misleading use of the term resistance for all forms of ecclesiastical opposition, “Evangelischer Widerstand” as a flawed educational resource.

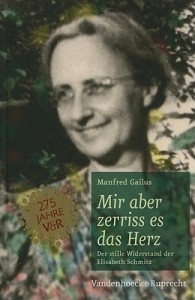

Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history Mir aber zerriss es das Herz. Der stille Widerstand der Elisabeth Schmitz (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010), Elisabeth Schmitz was a remarkable figure. A member of the “World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches” from 1928 on, she conscientiously taught religion, history, and German to high school students but refused to join the National Socialist Teachers’ Association. Instead, she joined the Confessing Church, soon criticizing its spokesmen for their disparaging comments about Jews and challenging its leaders to intervene on behalf of “non-Aryan” Germans. This protest culminated in her 1935 memorandum “On the Situation of German Non-Aryans,” described by the website as “arguably the most explicit protest within the Confessing Church against the persecution of Jews.” Schmitz wrote that the German Church was “inescapably entangled in this collective culpability” and could hardly expect forgiveness when “it forsakes its members in their desperate straits day for day, stands by and watches the flouting of all of God’s commandments, does not even venture to confess the public sin, but instead—remains silent?” Alongside this work within the Confessing Church, Schmitz courageously quit her teaching position in 1938. Applying for early retirement, she informed the Berlin school board that, “I have become increasingly doubtful whether I can teach my purely ideological subjects—religion, history, German—as the Nazi state expects and demands of me,” adding that, “this constant moral conflict has become unbearable.” She spent the rest of the war years aiding persecuted Jews, returning to the classroom once again after the Hitler regime had been swept away.

Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history Mir aber zerriss es das Herz. Der stille Widerstand der Elisabeth Schmitz (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010), Elisabeth Schmitz was a remarkable figure. A member of the “World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches” from 1928 on, she conscientiously taught religion, history, and German to high school students but refused to join the National Socialist Teachers’ Association. Instead, she joined the Confessing Church, soon criticizing its spokesmen for their disparaging comments about Jews and challenging its leaders to intervene on behalf of “non-Aryan” Germans. This protest culminated in her 1935 memorandum “On the Situation of German Non-Aryans,” described by the website as “arguably the most explicit protest within the Confessing Church against the persecution of Jews.” Schmitz wrote that the German Church was “inescapably entangled in this collective culpability” and could hardly expect forgiveness when “it forsakes its members in their desperate straits day for day, stands by and watches the flouting of all of God’s commandments, does not even venture to confess the public sin, but instead—remains silent?” Alongside this work within the Confessing Church, Schmitz courageously quit her teaching position in 1938. Applying for early retirement, she informed the Berlin school board that, “I have become increasingly doubtful whether I can teach my purely ideological subjects—religion, history, German—as the Nazi state expects and demands of me,” adding that, “this constant moral conflict has become unbearable.” She spent the rest of the war years aiding persecuted Jews, returning to the classroom once again after the Hitler regime had been swept away.

“Evangelischer Widerstand” is less effective in more complex situations, as in the case of the journal Junge Kirche (Young Church). Ralf Retter’s thorough study of the Confessing Church periodical, published as Zwischen Protest und Propaganda: Die Zeitschrift “Junge Kirche“ im Dritten Reich (Munich: Allitera Verlag, 2009), argues that the journal was engaged in Resistenz (non-conformity) though not Widerstand (opposition) between 1933 and 1936. During this time, it opposed the German Christian takeover of the church governments, promoted the Barmen Confession, opposed both the introduction of the Aryan Paragraph in the churches and the abandonment of the Old Testament, affirmed the traditional historical narratives defending the long-standing presence of Christianity in Germany, supported the emergent ecumenical movement, and even criticized Nazi interference in the realm of the church. However, Retter also details the ways in which Junge Kirche abandoned the more radical Dahlemite branch of the Confessing Church after 1936, and how by 1939, its pro-Nazi editorial tendencies were growing clearer and clearer. When Junge Kirche linked its embrace of Hitler’s war aims with its mission to foster piety and provide spiritual encouragement among German Protestants during the Second World War, it’s editors turned it into a stabilizing presence in the Third Reich—quite the opposite of a force for resistance.

In contrast to Retter’s nuanced portrayal, the online article “The Magazine ‘Junge Kirche’” (part of the “Christian Resistance” stream) explains how the church press “played a crucial role in communication and the exchange of information within church opposition.” It explains how Junge Kirche served as a “forum for opinions within the Confessing Church” and a source of information about wider German church life. It describes, quite rightly, how Nazi censorship limited the journal’s ability to report on church news and how the editors circumvented regulations by quoting Nazi or German Christian press reports, publishing the journal under a separate “Verlag Junge Kirche” in order to protect the real publisher, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. However, the decline of the journal as a forum for protest is greatly minimized, while there is no mention of its support for aspects of Nazism. The online text reads as follows:

Pressure on the editorial staff of the “Junge Kirche” to conform increased steadily, especially after the Nazi government changed its church policy in 1935. The balancing act between conformity and self-assertion grew more and more challenging. Government regulations had become so drastic by 1938 that the still remaining independent church press no longer had any latitude to report independently. The Reich Chamber of the Press eventually ordered the discontinuation of all religiously motivated magazines in the summer of 1941 on account of the war.

In the end, then, the website “Evangelischer Widerstand” is a bold and innovative attempt to present the history of Christian resistance to a new generation. It holds great potential to become the leading online educational site for the history of German Protestantism under Hitler. For that very reason, it is incumbent upon the editors from the Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History to define and contextualize their use of “Christian Resistance.” Doing so would make their dynamic website into the premier Internet source of information about all aspects of the history of German Protestantism in the Third Reich—from the heroic to the disgraceful.

Dohnanyi had been trained as a constitutional lawyer and had held significant posts in the Ministry of Justice. But he had early on become dismayed at the illegal activities and political violence of the Nazi extremists and had in fact drawn up a dossier which documented these misdeeds in full detail. Continue reading

Dohnanyi had been trained as a constitutional lawyer and had held significant posts in the Ministry of Justice. But he had early on become dismayed at the illegal activities and political violence of the Nazi extremists and had in fact drawn up a dossier which documented these misdeeds in full detail. Continue reading

George Bell was born in 1883 on the south coast of England, into a “secure, comfortable middle-class clerical home” (7). He attended Westminster School beginning in 1896, then Christ Church, Oxford, in 1901. Next he enrolled in theological college in Wells, in the West of England, where he was introduced to the student ecumenical movement and to Christian Socialism. Ordained as a deacon in Ripon Cathedral in 1907 and as a priest in Leeds in 1908, Bell returned to Oxford in 1910, where he combined a growing commitment to social justice with a vibrant personal faith. As he explained, “Christianity is a life before it is a system and to lay too much stress on the system destroys the life” (12).

George Bell was born in 1883 on the south coast of England, into a “secure, comfortable middle-class clerical home” (7). He attended Westminster School beginning in 1896, then Christ Church, Oxford, in 1901. Next he enrolled in theological college in Wells, in the West of England, where he was introduced to the student ecumenical movement and to Christian Socialism. Ordained as a deacon in Ripon Cathedral in 1907 and as a priest in Leeds in 1908, Bell returned to Oxford in 1910, where he combined a growing commitment to social justice with a vibrant personal faith. As he explained, “Christianity is a life before it is a system and to lay too much stress on the system destroys the life” (12). Mit Herz und Verstand is one of his recent additions to the literature. In addition to the fine overview of the topic in the introduction by Gailus and co-editor Clemens Vollnhals, it consists of biographical and historical profiles of Agnes and Elisabet von Harnack, Elisabeth Abegg, Elisabeth Schmitz, Elisabeth Schiemann, Margarete Meusel, Katharina Staritz, Agnes Wendland and her daughters Ruth and Angelika, Helene Jacobs, Sophie Benfey-Kunert, Elisabeth von Thadden, and Ina Gschlössl.

Mit Herz und Verstand is one of his recent additions to the literature. In addition to the fine overview of the topic in the introduction by Gailus and co-editor Clemens Vollnhals, it consists of biographical and historical profiles of Agnes and Elisabet von Harnack, Elisabeth Abegg, Elisabeth Schmitz, Elisabeth Schiemann, Margarete Meusel, Katharina Staritz, Agnes Wendland and her daughters Ruth and Angelika, Helene Jacobs, Sophie Benfey-Kunert, Elisabeth von Thadden, and Ina Gschlössl. Some of the highlights of the collection include the lead essay by Wolfgang Huber in which he provides a theological profile of Bonhoeffer’s political resistance, particularly his involvement in Hans von Dohnanyi’s conspiracy in the Abwehr. Despite the limitations placed on what Bonhoeffer could put into writing during the Third Reich, Huber believes a “theology of resistance” can be teased out of Bonhoeffer’s writing during this time. His call for the Church to take a public stand in solidarity with the Jews against the repressive state; his formulation of a confession of guilt in the name of the church; his theory of a responsible life; and his trust in God’s guidance—all indicate the rudiments of a theology of resistance, Huber believes.

Some of the highlights of the collection include the lead essay by Wolfgang Huber in which he provides a theological profile of Bonhoeffer’s political resistance, particularly his involvement in Hans von Dohnanyi’s conspiracy in the Abwehr. Despite the limitations placed on what Bonhoeffer could put into writing during the Third Reich, Huber believes a “theology of resistance” can be teased out of Bonhoeffer’s writing during this time. His call for the Church to take a public stand in solidarity with the Jews against the repressive state; his formulation of a confession of guilt in the name of the church; his theory of a responsible life; and his trust in God’s guidance—all indicate the rudiments of a theology of resistance, Huber believes. This short selection of texts written by seven notable Germans who resisted the Nazi onslaught against their Christian faith will be a helpful introduction for beginners in this field. While the testimonies of Dietrich Bonhoeffer have been known in English translation for many years, it is good to have these brief and excellently translated extracts from the writings of lesser known figures, such as Sophie Scholl, the Munich student executed for her protests against Nazi totalitarianism, or of Jochen Klepper, the well-known novelist, who committed suicide with his Jewish wife in 1942. On the Catholic side, the Jesuit Father Alfred Delp was also executed for his involvement with the July 1944 plot to overthrow Hitler. His prison letters are, like Bonhoeffer’s, an inspiring witness to his enduring faith. Less known to English-speaking readers will be the testimony of Franz Jägerstätter, the Austrian farmer, executed for his refusal to serve in Hitler’s army, or the courageous stand of the Berlin Cathedral Provost, Bernhard Lichtenberg, who prayed publicly for the persecuted Jews and for the prisoners in concentration camps, for which he was arrested and sent to prison. The only survivor, the Jesuit Father Rupert Mayer, was already arrested in 1937 for his provocative sermons critical of the regime. His refusal to be silenced led to his being imprisoned again in 1938, and then to being placed under house arrest in a distant monastery in 1940. The common theme of all these witnesses was their determination to protest against the injustices of the Nazi regime, even though their motives for doing so varied widely. They were all well aware of their isolation in adopting such views, but were resolved to defend the integrity of their Christian beliefs. Their readiness to challenge the majority’s obeisance, gullibility or fearfulness is what makes these testimonies so compelling. This little book will undoubtedly help to uphold their memory among a wider public, in the hope that their sacrifices will resonate far beyond their own times or their original homeland.

This short selection of texts written by seven notable Germans who resisted the Nazi onslaught against their Christian faith will be a helpful introduction for beginners in this field. While the testimonies of Dietrich Bonhoeffer have been known in English translation for many years, it is good to have these brief and excellently translated extracts from the writings of lesser known figures, such as Sophie Scholl, the Munich student executed for her protests against Nazi totalitarianism, or of Jochen Klepper, the well-known novelist, who committed suicide with his Jewish wife in 1942. On the Catholic side, the Jesuit Father Alfred Delp was also executed for his involvement with the July 1944 plot to overthrow Hitler. His prison letters are, like Bonhoeffer’s, an inspiring witness to his enduring faith. Less known to English-speaking readers will be the testimony of Franz Jägerstätter, the Austrian farmer, executed for his refusal to serve in Hitler’s army, or the courageous stand of the Berlin Cathedral Provost, Bernhard Lichtenberg, who prayed publicly for the persecuted Jews and for the prisoners in concentration camps, for which he was arrested and sent to prison. The only survivor, the Jesuit Father Rupert Mayer, was already arrested in 1937 for his provocative sermons critical of the regime. His refusal to be silenced led to his being imprisoned again in 1938, and then to being placed under house arrest in a distant monastery in 1940. The common theme of all these witnesses was their determination to protest against the injustices of the Nazi regime, even though their motives for doing so varied widely. They were all well aware of their isolation in adopting such views, but were resolved to defend the integrity of their Christian beliefs. Their readiness to challenge the majority’s obeisance, gullibility or fearfulness is what makes these testimonies so compelling. This little book will undoubtedly help to uphold their memory among a wider public, in the hope that their sacrifices will resonate far beyond their own times or their original homeland. The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” (

The interactive website “Evangelischer Widerstand” ( This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.)

This is the website developed over the past couple of years by the Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte (Protestant Working Group for Contemporary Church History) in Munich, under the leadership of Dr. Claudia Lepp, along with Drs. Siegfried Hermle, Harry Oelke, and a host of other notable German scholars. It is sponsored by the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and the Köber Foundation of Hamburg, and supported by a long list of academics, Protestant notables, archives, memorial sites, and other institutions. It contains information on no less than three dozen (as of March 2013) individual or group resisters, along with a timeline, a series of fundamental questions, photos, documents and audio clips. It is a rich and growing set of resources, tied to a substantial bibliography of German-language publications on the topics of resistance and the German churches under Hitler. (Hopefully, over time, the bibliography will grow to include many of the important English-language studies on the German churches in the Nazi era.) In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.”

In the “About the exhibition” section of the site, Claudia Lepp and her colleagues explain their historical assumptions and methodology. They argue that the resistance against National Socialism “continues to be one of the most volatile chapters of twentieth century German history,” express their concern about “the progressive loss of communicative memory from eyewitnesses to events,” and note “the problematic nature of resistance.” Delving into the historiography of the German churches under Nazism, they identify a shift during the 1980s away from a focus on the Confessing Church and towards four new issues: 1) the role of resistance in the everyday life of Christian congregations and the question of who was motivated by their Christian faith to aid the victims of persecution; 2) the significance of “less noted” groups like the Religious Socialists, liberal Christians, Christians in the National Committee for Free Germany, conscientious objectors and those who deserted on account of their Christian faith; 3) the personal faith of resistance members and its relationship to their ethical and political thinking; and 4) the proper historical presentation of resistance “detached from forms of heroization.” A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship.

A similar analysis could be made of the timeline. Here the web historians offer up three streams of articles—on the “Regime,” on “Majority Protestantism,” and on “Christian Resistance.” There are entries about Hitler’s misleading pro-Christian statements, the German Christian Faith Movement, and other aspects of the history of Protestant collaboration with the Hitler state. Still, in the crucial 1933-1934 section, the 19 articles devoted to aspects of Christian Resistance are almost double the 10 entries given over to the compromised majority Protestants, once more creating the impression that Christian Resistance was, in fact, the most obvious Christian response to the Nazi dictatorship. Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history

Because of these two weaknesses in the website’s approach to presenting the history of the German churches in the Third Reich, “Evangelischer Widerstand” works best when it tells the stories of the heroic, deeply-principled Christians who acted decisively against the regime and its policies. Elisabeth Schmitz is a good example. Just as Manfred Gailus has recently argued in his fine history