Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 31, Number 2 (Summer 2025)

Jörg Seiler, ed. Literatur – Gender – Konfession: Katholische Schriftstellerinnen, Vol. 1. Forschungsperspektiven. Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet, 2018, pp. 216.

Antonia Leugers, Literatur – Gender – Konfession: Katholische Schriftstellerinnen .Vol. 2. Analysen und Ergebnisse. Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet, 2020, pp. 288.

Dominik Schindler, “Michael von Faulhaber und die katholische Frauenbewegung (1903-1917). Zeitgemäße Seelsorge eines modernen Bischofs.” In Katharina Krips, Stephan Mokry, Klaus Unterburger, eds. Aufbruch in der Zeit: Kirchenreform und europäischer Katholizismus. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer, 2020, pp. 207-220.

By Martin Menke, Rivier University

In the ever-widening definition of church history, the role of women of faith remains an open field. The three contributions under review here demonstrate not only the extent of research that remains to be done but also the significant contribution that Christian women’s history makes to a greater understanding of Christian life in general, especially in the twentieth century. The first two volumes under consideration are the result of a multi-year grant-funded study on Catholic women authors from 1900 to the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), while the single chapter throws new light on the support of Michael von Faulhaber, before his appointment as archbishop of Munich, for Catholic women’s groups as well as his views of the woman’s role in church and society.

The study on Catholic women authors was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and based at the University of Erfurt. Antonia Leugers, Jörg Seiler, and Lucia Scherzberg, well-known historians of German Catholicism, as well as other church historians and several literature scholars and experts in database-supported research, collaborated on this study. Establishing a database of 160 Catholic women authors, as many as the grant permitted, the participants welcome future scholars to append additional writers, especially from earlier and later periods, to the historical record.

The study on Catholic women authors was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and based at the University of Erfurt. Antonia Leugers, Jörg Seiler, and Lucia Scherzberg, well-known historians of German Catholicism, as well as other church historians and several literature scholars and experts in database-supported research, collaborated on this study. Establishing a database of 160 Catholic women authors, as many as the grant permitted, the participants welcome future scholars to append additional writers, especially from earlier and later periods, to the historical record.

Based on theoretical concepts such as Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of “symbolic power” and Kimberlé Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality, the researchers inquired how these women fared as women authors and whether the authors met contemporary ideals concerning Catholic women. Did they dedicate their careers to upholding these ideals? Did identifiable subgroups exist? Which works caused scandal, which were forbidden, either by the Reichsschrifttumskammer or the Allied powers? Which authors went into exile? How did that experience change their views? While the volumes answer these questions, they lack effective summaries that conclude “indicators of processes by which these authors emancipated themselves from church norms by analyzing their fictitious characters” (vol. II, Leugers, p. 10) The authors of this volume analyze the degree to which Catholic women authors, in their personal lives and their fiction, adhere to the Catholic image of womanhood promoted by both the church and secular society, especially by the National Socialist regime. Many authors in their lives and their works differ from both Church and social expectations in matters of marriage, chastity, parenthood, and gender.

Instead, the volumes offer a wealth of case studies. Some of the authors, such as Gertrud von le Fort and Hedwig Dransfeld, were well-known, while others published only a few works. Each of the authors has their history. The Leugers volume includes a primarily quantitative summary of the women’s experiences, how many got divorced, converted to Catholicism, left the church, lived in same-sex relationships, had children out of wedlock, attempted suicide, chose cremation, were childless, etc. Leugers admits, however, that such personal information is sometimes difficult to obtain and that, given the limited sample, the data are more “symptomatic” than representative. This detailed qualitative analysis, however, lacks explanatory power. The more important questions raised in the project remain unanswered. The authors offer no conclusions about Catholic women’s emancipation, their understanding of gender, chastity, and parenthood. While some suggest disapproval of modernity, most suggest ways of accommodating it while maintaining a life of faith. In all cases, Catholic faith triumphs. Beyond this, however, this rich body of evidence cries for additional meaningful analysis. One wonders if these volumes report results from which results can be drawn.

Instead, the volumes offer a wealth of case studies. Some of the authors, such as Gertrud von le Fort and Hedwig Dransfeld, were well-known, while others published only a few works. Each of the authors has their history. The Leugers volume includes a primarily quantitative summary of the women’s experiences, how many got divorced, converted to Catholicism, left the church, lived in same-sex relationships, had children out of wedlock, attempted suicide, chose cremation, were childless, etc. Leugers admits, however, that such personal information is sometimes difficult to obtain and that, given the limited sample, the data are more “symptomatic” than representative. This detailed qualitative analysis, however, lacks explanatory power. The more important questions raised in the project remain unanswered. The authors offer no conclusions about Catholic women’s emancipation, their understanding of gender, chastity, and parenthood. While some suggest disapproval of modernity, most suggest ways of accommodating it while maintaining a life of faith. In all cases, Catholic faith triumphs. Beyond this, however, this rich body of evidence cries for additional meaningful analysis. One wonders if these volumes report results from which results can be drawn.

Determining a work’s effect, i.e., its reception history, remains difficult. The project includes contemporary critiques of the authors’ works, mostly by Catholic publications. Many of the works were considered trivial. Those authors who adhered most closely to Catholic moral standards tended to fare well in the reviews. Those who problematized Catholic teaching or offered differentiated explanations of human behavior were often condemned by church authorities and Catholic publications. For the period 1933-1945, the detailed records of the Reichsschriftumskammer, which evaluated the publications for ideological conformity or at least compatibility, offer insights into the works. One of the regime’s objections was the Catholic praise for virginity and chastity. The regime denigrated women who chose not to bear children. A final measure of a work’s popularity was the number of volumes printed. In some cases, new editions were published well after the war, while other works sold only a few hundred copies.

While the research summary volume by Leugers, the second in the trilogy, focuses on the various types of Catholic women authors, the contributors to the Seiler volume, the first in the series (these two volumes are reviewed here; the third volume, also edited by Seiler, discusses the literary conflict between Carl Muth and more conservative, orthodox groups), offer insights useful for future scholars. Lucia Scherzberg, for example, analyzes the gendering of God throughout history and how Protestantism is often defined as male, while Catholicism is usually described as female. She asks how the authors constructed gender and what role religious affiliation plays in constructing gender. In general, she inquires about the role that gender plays in the thinking and works of these authors. Scherzberg provides no answers and poses these questions to future scholars.

In an apparent rebuke to Leugers, Scherzberg also questions “whether or not social scientific theory can capture the contingency of historical processes.” Social scientific theories often cannot provide micro-historical explanations.

Günter Häntzschel discusses Catholic lyric poetry. Interesting is his summary of the conflict between Carl Muth, who founded Hochland, the premier intellectual Catholic journal of the period before World War II, and who sought to establish Catholic literature independent of Catholic teaching, and Richard Gralik, who founded the Gral as a conservative Catholic magazine. Muth became the driving force behind an independent non-ecclesiastical Catholic intellectual life in Germany. Maria Cristina Giacomin addresses Muth’s concern about inferior Catholic literature more directly. Muth feared that Catholic literature, directed primarily at women and older girls, had been feminized. The first novel by a woman that Muth published in Hochland was a complex account of an anti-Catholic man and the Catholic woman who denounces him as a Lutheran for blasphemous desecration, but also reconciles him with the Catholic faith. Gendered religious identities, erotic undertones, and the protagonist’s refusal to bear children yielded much criticism. Giacomin argues that Catholic readers at the time were accustomed to clearly didactic novels in which the Catholic moral lesson was presented unambiguously.

Regina Heyder explains that while Catholics considered women’s chastity and virginity laudable before 1945, in the post-war era, chastity was considered a burdensome outcome of fate. Several authors explain that Catholic women authors described convent schools as places of repression and punishment, but also, more importantly, as places dominated by obscurantism and “void of intellectual and artistic nourishment” (Seiler, 166).

Martin Papenbrock analyzes book covers from the Beaux-Arts style to post-war modernity. While offering little commentary on the works’ Catholicism, he notes that publishers often commission book covers that do not accurately reflect the nuanced discussions provided in the text. They reflect more the times in which the book was published than its contents.

While both volumes lack an analytical, summative conclusion, they complicate scholars’ understanding of twentieth-century Catholicism. Women who read and could afford books, or who sought out lending libraries, were offered a differentiated and challenging image of Catholic womanhood, one that demands further analysis and explanation. These works paint a more complicated picture of Catholic womanhood, as the views of womanhood discussed in these volumes were ascribed to Catholic men of their subjects’ time, and ecclesiastical concerns about “modern” Catholic women. Most importantly, the volumes offer evidence of the significance to Catholic social, moral and cultural history of women’s agency.

Another instance in which women’s agency proved important can be found in Dominik Schindler’s discussion of the relationship between the Katholische Deutsche Frauenbund and Michael von Faulhaber, a theology professor at Strasbourg and bishop of Speyer. In a nuanced brief essay, Schindler argues that Faulhaber actively supported the formation of the Frauenbund and the Hildburgisbund, an organization supporting female university students. According to Schindler, Faulhaber largely adhered to traditional values, but insisted that Catholic values reflect the equal role many Catholic women played in securing the family’s income. He also argued publicly that Catholic theology proved no obstacle to women’s suffrage. While men remained heads of household, this did not consign women to second-class status. Faulhaber’s view of the family remained conservative. Still, he acknowledged that in an industrial society, a man’s wages might not suffice to meet the family’s expenses, and thus a woman might be forced to work. Faulhaber argued that women from the upper classes should be encouraged to participate in social and cultural life. In contrast, women in the lower classes deserved much support to earn an honorable living. He believed that women’s work was necessary to meet the needs of their children. Schindler argues that, even if Faulhaber’s views seem backward today, at the time, they were quite progressive.

Another instance in which women’s agency proved important can be found in Dominik Schindler’s discussion of the relationship between the Katholische Deutsche Frauenbund and Michael von Faulhaber, a theology professor at Strasbourg and bishop of Speyer. In a nuanced brief essay, Schindler argues that Faulhaber actively supported the formation of the Frauenbund and the Hildburgisbund, an organization supporting female university students. According to Schindler, Faulhaber largely adhered to traditional values, but insisted that Catholic values reflect the equal role many Catholic women played in securing the family’s income. He also argued publicly that Catholic theology proved no obstacle to women’s suffrage. While men remained heads of household, this did not consign women to second-class status. Faulhaber’s view of the family remained conservative. Still, he acknowledged that in an industrial society, a man’s wages might not suffice to meet the family’s expenses, and thus a woman might be forced to work. Faulhaber argued that women from the upper classes should be encouraged to participate in social and cultural life. In contrast, women in the lower classes deserved much support to earn an honorable living. He believed that women’s work was necessary to meet the needs of their children. Schindler argues that, even if Faulhaber’s views seem backward today, at the time, they were quite progressive.

The three works in question raise more questions than they answer, but there is justification for such works. While Laura Fetheringill Zwicker, Martina Cucchiara, and others, including the scholarship reviewed here, have made inroads into German Catholic women’s history, much work remains to be done, work that will enrich the record and challenge scholars to be sensitive to greater differentiation.

Mary Fulbrook is Professor of German History at University College London. She is a familiar and respected contributor to scholarship on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. In this work she avoids teleological interpretations of events and rejects simplistic categorizations. She endeavors to tell the story of German bystanders “from the inside out” through “selected accounts of personal experiences” (16). She tells the stories of individuals. In so doing, she humanizes history. Victims and bystanders had names. They had stories. They were not a grouping of data points on a chart. Fulbrook’s subjects are profoundly human, and their complex stories challenge facile characterizations of society in Nazi Germany. Fulbrook’s primary sources for Part I are autobiographical essays from 1939 written on the theme “My life in Germany before and after January 30, 1933.” These essays give a broad range of everyday experiences before such memories were shaped by knowledge of the horrors of the Holocaust. Likewise, in Part II she employs a variety of firsthand accounts and memoirs to tell stories from the ground level. Fulbrook argues well for the value and limitations of her source base in her introduction.

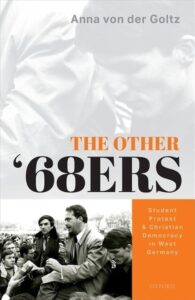

Mary Fulbrook is Professor of German History at University College London. She is a familiar and respected contributor to scholarship on Nazi Germany and the Holocaust. In this work she avoids teleological interpretations of events and rejects simplistic categorizations. She endeavors to tell the story of German bystanders “from the inside out” through “selected accounts of personal experiences” (16). She tells the stories of individuals. In so doing, she humanizes history. Victims and bystanders had names. They had stories. They were not a grouping of data points on a chart. Fulbrook’s subjects are profoundly human, and their complex stories challenge facile characterizations of society in Nazi Germany. Fulbrook’s primary sources for Part I are autobiographical essays from 1939 written on the theme “My life in Germany before and after January 30, 1933.” These essays give a broad range of everyday experiences before such memories were shaped by knowledge of the horrors of the Holocaust. Likewise, in Part II she employs a variety of firsthand accounts and memoirs to tell stories from the ground level. Fulbrook argues well for the value and limitations of her source base in her introduction. The primary argument of the book is that conservative student activists, and especially leaders of the Ring Christlich-Demokratischer Studenten (Association of Christian Democratic Students or RCDS), were not only present during the 68er generation’s protests but were meaningful actors that shaped many of the era’s signature events. The photographs and opening anecdotes to each chapter alone convincingly prove this point. The cover photo shows a famous debate in Freiburg between the older liberal academic Ralf Dahrendorf and young Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentbund (SDS) figurehead Rudi Dutschke. Lurking in the margins of the photo are young Christian Democrats, Meinhard Ade and Ignaz Bender, who helped organize the event and participated in the debate. Von der Goltz emphasizes how these two students are rarely recognized and sometimes even cropped out of this famous photo to illustrate how the primary subjects of her inquiry have been overlooked. The presence of Ade and Bender at the debate is nonetheless significant. On the one hand, they positioned themselves against their generational spokesperson, Dutschke, and spoke out against left-wing radicalism. On the other hand, their willingness to dialogue with left-wing students and their embrace of the liberal Dahrendorf distinguished them from the older generations of Christian Democrats. Another chapter opens by revealing that the RCDS had organized the visit of the South Vietnamese ambassador in 1966, which Rudi Dutschke and the SDS interrupted, to intentionally draw national attention to the New Left’s unpopular protest tactics. Additionally, the fifth chapter opens with a description of when RCDS chair Gerd Langguth held his ground, condemning the constitutional threat posed by the Marxist Student Association Spartakus while being pelted by cheese curds in 1972. Such examples highlight the often-forgotten role of the right in these moments of protest and illustrates how young Christan Democrats initiated dialogue about reform in the 1960s, imitated many of the theatrical tactics of their left-wing adversaries, and eventually condemned the far-left’s militant turn in the 1970s.

The primary argument of the book is that conservative student activists, and especially leaders of the Ring Christlich-Demokratischer Studenten (Association of Christian Democratic Students or RCDS), were not only present during the 68er generation’s protests but were meaningful actors that shaped many of the era’s signature events. The photographs and opening anecdotes to each chapter alone convincingly prove this point. The cover photo shows a famous debate in Freiburg between the older liberal academic Ralf Dahrendorf and young Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentbund (SDS) figurehead Rudi Dutschke. Lurking in the margins of the photo are young Christian Democrats, Meinhard Ade and Ignaz Bender, who helped organize the event and participated in the debate. Von der Goltz emphasizes how these two students are rarely recognized and sometimes even cropped out of this famous photo to illustrate how the primary subjects of her inquiry have been overlooked. The presence of Ade and Bender at the debate is nonetheless significant. On the one hand, they positioned themselves against their generational spokesperson, Dutschke, and spoke out against left-wing radicalism. On the other hand, their willingness to dialogue with left-wing students and their embrace of the liberal Dahrendorf distinguished them from the older generations of Christian Democrats. Another chapter opens by revealing that the RCDS had organized the visit of the South Vietnamese ambassador in 1966, which Rudi Dutschke and the SDS interrupted, to intentionally draw national attention to the New Left’s unpopular protest tactics. Additionally, the fifth chapter opens with a description of when RCDS chair Gerd Langguth held his ground, condemning the constitutional threat posed by the Marxist Student Association Spartakus while being pelted by cheese curds in 1972. Such examples highlight the often-forgotten role of the right in these moments of protest and illustrates how young Christan Democrats initiated dialogue about reform in the 1960s, imitated many of the theatrical tactics of their left-wing adversaries, and eventually condemned the far-left’s militant turn in the 1970s. Based on her 2017 dissertation in Protestant theology at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Loos presents a meticulously researched, insightful, and densely written work on German Protestant attitudes toward communism in general (ideas, ideologies, organizations) and Soviet communist-Bolshevism in particular. Occasionally referencing pre-World War I events, her focus is Germany’s political transition through the Weimar Republic into the Third Reich, tracing the intensification of anti-communist rhetoric on the eve of World War II and the eventual military assault on the Soviet Union in 1941. While the opening chapter points to a few academic-theological debates at the turn of the century on possible family resemblances between the ideals of early Christian and communist communities, the last chapter briefly outlines post-war developments in the Protestant churches until the mid-1950s, with anti-communist stances, though more restrained, remaining largely intact.

Based on her 2017 dissertation in Protestant theology at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Loos presents a meticulously researched, insightful, and densely written work on German Protestant attitudes toward communism in general (ideas, ideologies, organizations) and Soviet communist-Bolshevism in particular. Occasionally referencing pre-World War I events, her focus is Germany’s political transition through the Weimar Republic into the Third Reich, tracing the intensification of anti-communist rhetoric on the eve of World War II and the eventual military assault on the Soviet Union in 1941. While the opening chapter points to a few academic-theological debates at the turn of the century on possible family resemblances between the ideals of early Christian and communist communities, the last chapter briefly outlines post-war developments in the Protestant churches until the mid-1950s, with anti-communist stances, though more restrained, remaining largely intact.

The study on Catholic women authors was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and based at the University of Erfurt. Antonia Leugers, Jörg Seiler, and Lucia Scherzberg, well-known historians of German Catholicism, as well as other church historians and several literature scholars and experts in database-supported research, collaborated on this study. Establishing a database of 160 Catholic women authors, as many as the grant permitted, the participants welcome future scholars to append additional writers, especially from earlier and later periods, to the historical record.

The study on Catholic women authors was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and based at the University of Erfurt. Antonia Leugers, Jörg Seiler, and Lucia Scherzberg, well-known historians of German Catholicism, as well as other church historians and several literature scholars and experts in database-supported research, collaborated on this study. Establishing a database of 160 Catholic women authors, as many as the grant permitted, the participants welcome future scholars to append additional writers, especially from earlier and later periods, to the historical record. Instead, the volumes offer a wealth of case studies. Some of the authors, such as Gertrud von le Fort and Hedwig Dransfeld, were well-known, while others published only a few works. Each of the authors has their history. The Leugers volume includes a primarily quantitative summary of the women’s experiences, how many got divorced, converted to Catholicism, left the church, lived in same-sex relationships, had children out of wedlock, attempted suicide, chose cremation, were childless, etc. Leugers admits, however, that such personal information is sometimes difficult to obtain and that, given the limited sample, the data are more “symptomatic” than representative. This detailed qualitative analysis, however, lacks explanatory power. The more important questions raised in the project remain unanswered. The authors offer no conclusions about Catholic women’s emancipation, their understanding of gender, chastity, and parenthood. While some suggest disapproval of modernity, most suggest ways of accommodating it while maintaining a life of faith. In all cases, Catholic faith triumphs. Beyond this, however, this rich body of evidence cries for additional meaningful analysis. One wonders if these volumes report results from which results can be drawn.

Instead, the volumes offer a wealth of case studies. Some of the authors, such as Gertrud von le Fort and Hedwig Dransfeld, were well-known, while others published only a few works. Each of the authors has their history. The Leugers volume includes a primarily quantitative summary of the women’s experiences, how many got divorced, converted to Catholicism, left the church, lived in same-sex relationships, had children out of wedlock, attempted suicide, chose cremation, were childless, etc. Leugers admits, however, that such personal information is sometimes difficult to obtain and that, given the limited sample, the data are more “symptomatic” than representative. This detailed qualitative analysis, however, lacks explanatory power. The more important questions raised in the project remain unanswered. The authors offer no conclusions about Catholic women’s emancipation, their understanding of gender, chastity, and parenthood. While some suggest disapproval of modernity, most suggest ways of accommodating it while maintaining a life of faith. In all cases, Catholic faith triumphs. Beyond this, however, this rich body of evidence cries for additional meaningful analysis. One wonders if these volumes report results from which results can be drawn. Another instance in which women’s agency proved important can be found in Dominik Schindler’s discussion of the relationship between the Katholische Deutsche Frauenbund and Michael von Faulhaber, a theology professor at Strasbourg and bishop of Speyer. In a nuanced brief essay, Schindler argues that Faulhaber actively supported the formation of the Frauenbund and the Hildburgisbund, an organization supporting female university students. According to Schindler, Faulhaber largely adhered to traditional values, but insisted that Catholic values reflect the equal role many Catholic women played in securing the family’s income. He also argued publicly that Catholic theology proved no obstacle to women’s suffrage. While men remained heads of household, this did not consign women to second-class status. Faulhaber’s view of the family remained conservative. Still, he acknowledged that in an industrial society, a man’s wages might not suffice to meet the family’s expenses, and thus a woman might be forced to work. Faulhaber argued that women from the upper classes should be encouraged to participate in social and cultural life. In contrast, women in the lower classes deserved much support to earn an honorable living. He believed that women’s work was necessary to meet the needs of their children. Schindler argues that, even if Faulhaber’s views seem backward today, at the time, they were quite progressive.

Another instance in which women’s agency proved important can be found in Dominik Schindler’s discussion of the relationship between the Katholische Deutsche Frauenbund and Michael von Faulhaber, a theology professor at Strasbourg and bishop of Speyer. In a nuanced brief essay, Schindler argues that Faulhaber actively supported the formation of the Frauenbund and the Hildburgisbund, an organization supporting female university students. According to Schindler, Faulhaber largely adhered to traditional values, but insisted that Catholic values reflect the equal role many Catholic women played in securing the family’s income. He also argued publicly that Catholic theology proved no obstacle to women’s suffrage. While men remained heads of household, this did not consign women to second-class status. Faulhaber’s view of the family remained conservative. Still, he acknowledged that in an industrial society, a man’s wages might not suffice to meet the family’s expenses, and thus a woman might be forced to work. Faulhaber argued that women from the upper classes should be encouraged to participate in social and cultural life. In contrast, women in the lower classes deserved much support to earn an honorable living. He believed that women’s work was necessary to meet the needs of their children. Schindler argues that, even if Faulhaber’s views seem backward today, at the time, they were quite progressive.

Under the terms of the Hitler-Mussolini Agreement, all those South Tyroleans who retained Austrian citizenship after 1919 were now considered citizens of the Reich. They had no choice but to resettle in post-Anschluss Germany. South Tyroleans who had become Italians in 1919 were given a choice. They could opt for Germany and be resettled as German citizens in Germany, or remain and be confirmed in their Italian citizenship. Lamprecht successfully illustrates the painful decisions that South Tyroleans, lay and clergy, had to make. As a result of effective German propaganda and Italian fascist repression, more than eighty percent of South Tyroleans opted for Germany. South Tyrolean laypeople opted for Germany primarily out of resentment of Italian fascism and Italianization policies. The clergy in the parishes, however, found the decision much more difficult. Most sought to remain in their homeland.

Under the terms of the Hitler-Mussolini Agreement, all those South Tyroleans who retained Austrian citizenship after 1919 were now considered citizens of the Reich. They had no choice but to resettle in post-Anschluss Germany. South Tyroleans who had become Italians in 1919 were given a choice. They could opt for Germany and be resettled as German citizens in Germany, or remain and be confirmed in their Italian citizenship. Lamprecht successfully illustrates the painful decisions that South Tyroleans, lay and clergy, had to make. As a result of effective German propaganda and Italian fascist repression, more than eighty percent of South Tyroleans opted for Germany. South Tyrolean laypeople opted for Germany primarily out of resentment of Italian fascism and Italianization policies. The clergy in the parishes, however, found the decision much more difficult. Most sought to remain in their homeland.

Another aunt, on the other hand, talks incessantly about the damnation that awaits Hirneise because of her turning away from God. For this aunt, there is no reality outside of faith, which is why she constantly asks God for forgiveness for Hirneise and her mother. This aunt’s husband is also strictly religious, but unlike his wife, he accepts scientific views to explain the world. For example, he sees the creation of the universe through the Big Bang as entirely possible. And he also accepts that people turn away from God, a stance that his own wife acknowledges with incomprehension. Hirneise’s mother, for her part, reports how her own mother (Hirneise’s grandmother with dementia) had demanded that her daughter remain completely abstinent until her husband—who, it should be noted, had left her—came back to her. The subject of the divorce is not discussed further, so it remains unclear why Hirneise’s father left the family. And of course, he never came back.

Another aunt, on the other hand, talks incessantly about the damnation that awaits Hirneise because of her turning away from God. For this aunt, there is no reality outside of faith, which is why she constantly asks God for forgiveness for Hirneise and her mother. This aunt’s husband is also strictly religious, but unlike his wife, he accepts scientific views to explain the world. For example, he sees the creation of the universe through the Big Bang as entirely possible. And he also accepts that people turn away from God, a stance that his own wife acknowledges with incomprehension. Hirneise’s mother, for her part, reports how her own mother (Hirneise’s grandmother with dementia) had demanded that her daughter remain completely abstinent until her husband—who, it should be noted, had left her—came back to her. The subject of the divorce is not discussed further, so it remains unclear why Hirneise’s father left the family. And of course, he never came back. In the second chapter, Pangritz addresses the problematic distinction between the terms anti-Judaism and antisemitism. He shows that the distinction between a theologically-argued hostility towards Jews and a racially argued antisemitism, which has been repeatedly postulated since the end of the Second World War, has not stood the test of time. On the contrary, such a distinction harbors the danger that (Christian) hatred of Jews is trivialized by juxtaposing it with antisemitism. Pangritz proposes “not to speak of a break, but rather of a transformation of the traditional Christian ‘doctrine of contempt’ (Lehre der Verachtung) into the modern forms of antisemitism” (35). It remains unclear, however, why Pangritz returns to the concept of anti-Judaism later in the book (e.g. 119). The term has been overused by Christian apologetics, and Pangritz himself has pointed out that the academic distinction between anti-Judaism and antisemitism has not produced any new insights or meaningful differentiations. (30). Conceptual clarity would have been helpful here, especially since Pangritz argues well with Léon Poliakov, Peter Schäfer and even Reinhard Rürup that “antisemitism” should be used in its most general sense: “The word ‘antisemitism’ denotes hostility, hatred and contempt of all kinds against Jews and Judaism; this does not exclude differences in motivation, but includes them” (33). However, this small point is the only criticism I can make in the entire book.

In the second chapter, Pangritz addresses the problematic distinction between the terms anti-Judaism and antisemitism. He shows that the distinction between a theologically-argued hostility towards Jews and a racially argued antisemitism, which has been repeatedly postulated since the end of the Second World War, has not stood the test of time. On the contrary, such a distinction harbors the danger that (Christian) hatred of Jews is trivialized by juxtaposing it with antisemitism. Pangritz proposes “not to speak of a break, but rather of a transformation of the traditional Christian ‘doctrine of contempt’ (Lehre der Verachtung) into the modern forms of antisemitism” (35). It remains unclear, however, why Pangritz returns to the concept of anti-Judaism later in the book (e.g. 119). The term has been overused by Christian apologetics, and Pangritz himself has pointed out that the academic distinction between anti-Judaism and antisemitism has not produced any new insights or meaningful differentiations. (30). Conceptual clarity would have been helpful here, especially since Pangritz argues well with Léon Poliakov, Peter Schäfer and even Reinhard Rürup that “antisemitism” should be used in its most general sense: “The word ‘antisemitism’ denotes hostility, hatred and contempt of all kinds against Jews and Judaism; this does not exclude differences in motivation, but includes them” (33). However, this small point is the only criticism I can make in the entire book.