Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 19, Number 4 (December 2013)

Review of Michael Wermke, ed., Transformation und religiöse Erziehung: Kontinuitäten und Brüche der Religionspädagogik 1933 und 1945 (Jena: IKS Garamond, 2011), 390 pp. ISBN 978-3941854376.

Heath A. Spencer, Seattle University

Standard works on German church history during the Nazi era often focus on the extent to which theologians, clergy, church administrations and church-run institutions supported, complied with, or resisted the aims of the Nazi state. Also of interest is the degree to which Nazi ideology permeated, shaped or undermined religious life among ordinary Protestants and Catholics. Transformation und religiöse Erziehung, edited by Michael Wermke, makes a valuable contribution on both levels through its investigation of the theory and practice of religious education before and during the Third Reich. The research included in this volume was originally presented at the annual conference of the Arbeitskreis für Historische Religionspädagogik in 2010. Although a few of the chapters are aimed solely at specialists in the history of religious education, most will be of wider interest to contemporary church historians as well.

Two of the chapters are biographical studies of individual religious educators or professors at teacher training institutions. Thomas Martin Schneider’s “Die Umbrüche 1933 und 1945 und die Religionspädagogik” takes up the story of Georg Maus, a religion teacher at an Oberschule in Idar- Oberstein. Maus, who was associated with the Confessing Church, was accused of undermining the war effort because he failed to properly manage a class discussion of Jesus’ command to love one’s enemies. He received a two-year sentence and died while being transported to Dachau. Schneider contrasts Maus’ story with that of Reinhold Krause, also an educator, but most famous for his address to members of the German Christian Movement at the Berlin Sport Palace Rally in 1933. Schneider finds that Krause both appropriated and violated aspects of liberal Protestant thought. The cases of Maus and Krause, Schneider argues, call into question both the “conservative decadence model” that blames liberal Protestant theology for Nazi conceptions of Christianity and the “progress- optimistic model” that exonerates it of all charges. Theological orientations, including diverse political theologies in the twentieth century, cannot be judged apart from their historical contexts. Likewise, one should not reduce contemporary religious education to the narrow range of options that were present in the Third Reich, nor should one assume that those options will have the same value in all historical settings.

Two of the chapters are biographical studies of individual religious educators or professors at teacher training institutions. Thomas Martin Schneider’s “Die Umbrüche 1933 und 1945 und die Religionspädagogik” takes up the story of Georg Maus, a religion teacher at an Oberschule in Idar- Oberstein. Maus, who was associated with the Confessing Church, was accused of undermining the war effort because he failed to properly manage a class discussion of Jesus’ command to love one’s enemies. He received a two-year sentence and died while being transported to Dachau. Schneider contrasts Maus’ story with that of Reinhold Krause, also an educator, but most famous for his address to members of the German Christian Movement at the Berlin Sport Palace Rally in 1933. Schneider finds that Krause both appropriated and violated aspects of liberal Protestant thought. The cases of Maus and Krause, Schneider argues, call into question both the “conservative decadence model” that blames liberal Protestant theology for Nazi conceptions of Christianity and the “progress- optimistic model” that exonerates it of all charges. Theological orientations, including diverse political theologies in the twentieth century, cannot be judged apart from their historical contexts. Likewise, one should not reduce contemporary religious education to the narrow range of options that were present in the Third Reich, nor should one assume that those options will have the same value in all historical settings.

The second biographical study is Folkert Rickers’ “’Vom Individuum zum Volksgenossen’: Helmuth Kittel und die Jugendbewegung.” In this work, Rickers explores the ideological orientation of Kittel, a youth movement leader, theologian, and professor of pedagogy. Kittel’s postwar autobiography minimizes his association with Nazism, but his writings from the 1920s and 1930s (more than 90 titles) indicate enthusiasm for völkisch ideology well before Hitler came to power. Contrary to his postwar claims, he seems to have experienced the Third Reich as the fulfillment of the goals of the German youth movement in which he played such a prominent role.

Jonas Flöter’s “Von der Landeschule zur Nationalpolitischen Erziehungsanstalt” examines the transition of the Landesschule Pforta, established in 1543, from an elite secondary school with a religious orientation to a de-Christianized training ground for political soldiers. The Reichsministerium für Wissenschaft, Erziehung, und Volksbildung exploited internal conflicts and scandals at the school in order to replace most teachers and administrators, and in 1935, SS member Dr. Adolf Schieffer was entrusted with the transformation of the school into an NPEA. However, religious services and religious instruction, including lessons in Hebrew and the Old Testament, were not abolished until 1937, and up to that point approximately two thirds of the students continued to participate in religion classes. In order to carry out the transformation of the school, the Reichserziehungsministerium had to work around school personnel, parents, students, and alumni who were not always fully compliant.

Five of the chapters in the collection focus on trends in Protestant and Catholic religious education at the regional and national levels. Werner Simon’s “Nationalpolitische Erziehung im katholischen Unterricht?” examines the writings of prominent Catholic theorists and contributors to Katechetische Blätter, a Catholic journal devoted to religious education. Simon finds considerable interest in 1933 and 1934 for “national-political education in Catholic religious instruction” (77), but there was little emphasis on such themes before or after that two-year period. In fact, articles published after 1934 were more likely to express opposition to what was seen as a Germanic narrowing of the faith or conflict between demands of the state and universal Christian ethics.

Joachim Maier’s “Traditionsbruch und Wandel religiöser Erziehung: Schule und katholischer Religionsunterricht in Baden 1933-1945” also suggests a blend of opposition and complicity on the part of German Catholics. After the Nazis came to power, church holidays and school prayers were replaced with National Socialist holidays and slogans. The new Hochschule für Lehrerbildung in Karlsruhe offered only minimal training in methods of religious education, and most teachers refused to teach religion in any case, especially if the Old Testament was part of the curriculum. As a result, many pious Catholics who initially had expressed enthusiasm for Hitler’s regime now viewed it with suspicion. Catholic leaders in Baden responded by publishing Katechismuswahrheiten (1936), a document that challenged Nazi racial ideology and stressed the importance of both the Old and New Testaments. Unfortunately, it also reinforced a number of anti-Jewish stereotypes and declared that German Catholics should give special consideration to their own Volk. Archbishop Conrad Gröber (Freiburg) sent mixed messages to the faithful by stressing obedience to the state and warning that “from the depravity and loss of faith among the youth it is only a very small step to the world view of our bitterest enemies in the east” (115). Nevertheless, Catholic authorities in Baden put up a more spirited defense of traditional religious instruction than Protestant leaders in the same region.

Desmond Bell’s “Ein Fehler im System? Das Alte Testament im preussischen Religionsunterricht nach 1933” illustrates the extent to which Prussian school curricula were stripped of religious content, especially that which was seen to be the result of Jewish influences. The National Socialist Teachers’ Association opposed religious instruction in general and the Old Testament in particular, whereas guidelines from the Protestant Reich Church administration called for removal of the Old Testament from religious instruction except those cases where it could be used to “demonstrate” that Jesus came to do battle with Judaism. Bell finds evidence that, in spite of these pressures, Old Testament material was still included in some religion texts as late as 1942. However, the content was reduced dramatically over time, and what was left was severed from Judaism and reframed in such a way as to promote an antisemitic and National Socialist worldview.

Johannes Wischmeyer’s “Transformationen des Bildungsraums im bayrischen ‘Schulkampf’ 1933-1938” focuses less on the religious curriculum within schools and more on the abolition of Protestant denominational school in Bavaria. In addition to curtailing religious instruction and removing clergy from teaching positions, both the state and the National Socialist Teachers’ Association put tremendous pressure on parents to send their children to Gemeinschaftschulen rather than denominational schools. This pressure included multiple home visits by teachers who denounced confessional schools as “residual schools” or “peasant schools” (128). The regional Bavarian Protestant Church responded with its own campaign to shore up support for denominational schools, but by 1936 only 2000 Protestant students remained enrolled, and the last denominational school was forced to close in 1937.

One of the most interesting contributions to the volume is David Käbisch’s, “Eine Typologie des Versagens? Das Personal und Lehrprofil für das Fach Religion an den nationalsozialistischen Hochschulen fur Lehrerbildung.” In this article, Käbisch surveys the available data on 818 religion courses offered at teacher training institutes throughout Germany, comparing what was taught before and after 1933. In addition to recommending approaches for further research, Käbisch identifies patterns that are already apparent. For example, after 1933 it was more common to see topics such as “The Protestant Faith as a Particular Expression of the German Character, Demonstrated by Great Men of German History (Luther, Bach, Arndt, Lagarde, Bismarck, Hindenburg, etc.)” (175). Of the courses offered between 1939 and 1945, 8 addressed explicitly Christological themes, 26 focused on Martin Luther, and 43 dealt with “contemporary problems.” It is also possible to track changes in the priorities of individual professors. For example, Fritz Hoffmann of the Pädagogische Akademie in Elbing taught courses on “The Kingdom of God in the Sermons of Jesus” and similar topics before 1933, but after 1933 he was teaching subjects like “German Christianity: State, Church and School” and “The German Concept of Honor and Christian Morality” (169, 185-189). Following Käbisch’s analysis, Appendix II (pages 174-214) includes a complete list of the individual courses, identifying the instructors, denominations, institutions, and dates.

One other chapter of interest to church historians is Hein Retter’s “Protestantische Milieus vor und nach 1933. Der Christlich-Soziale Volksdienst und der Reichsverband deutscher evangelischer Schulgemeinden e.V.” Both the political party and the school association in this study emerged out of free-church, Biblicist, and Pietistic circles in Württemberg, Westphalia, Hanover, and the Rhineland. Their supporters opposed rationalism, liberalism, and Marxism, yet they were also loyal to the Weimar Republic and willing to advance their culturally conservative agendas through a democratic process. Although many in the Schulgemeindeverband initially expressed enthusiasm for the Nazi state, seeing it as a solution to moral decline, it was not long before they moved toward a more oppositional stance. Retter applauds their publication of an agenda for religious instruction that was inspired by the Barmen Declaration, affirmed the important of both the Old and New Testaments, and refused to make National Socialism the standard for religious education.

Altogether, the contributors to this volume present a fascinating account of both continuity and change in religious education following the Nazi revolution in 1933. A few chapters address the postwar era as well, but overall this period receives less attention and the results are less striking. Several contributors mention the challenges posed by incomplete records and the limited range of the sources. For example, it is easier to identify the content of text books and course plans than to know what actually happened in the classroom and how it was experienced by children and youth. In spite of such limitations, this collective effort by the Arbeitskreis für Historische Religionspädagogik provides important insights into how the policies of state and church played out at the local level among ordinary people. They take us beyond institutional histories and church politics and into the world of students, teachers, professors, and parents, all of whom had their own role to play alongside religious and political leaders.

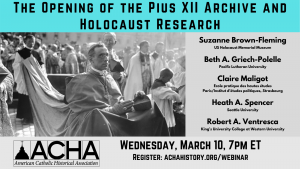

On March 10, 2021, the American Catholic Historical Association held a webinar entitled “The Opening of the Pius XI Archive and Holocaust Research.” Presenters included Suzanne Brown-Fleming, US Holocaust Memorial Museum: Beth A. Griech-Polelle, Pacific Lutheran University; Claire Maligot, Ecole pratique des hautes études, Paris, and Institut d’études politiques, Strasbourg; Heath A. Spencer, Seattle University; and Robert A. Ventresca, King’s University College at Western University.

On March 10, 2021, the American Catholic Historical Association held a webinar entitled “The Opening of the Pius XI Archive and Holocaust Research.” Presenters included Suzanne Brown-Fleming, US Holocaust Memorial Museum: Beth A. Griech-Polelle, Pacific Lutheran University; Claire Maligot, Ecole pratique des hautes études, Paris, and Institut d’études politiques, Strasbourg; Heath A. Spencer, Seattle University; and Robert A. Ventresca, King’s University College at Western University.

Two of the chapters are biographical studies of individual religious educators or professors at teacher training institutions. Thomas Martin Schneider’s “Die Umbrüche 1933 und 1945 und die Religionspädagogik” takes up the story of Georg Maus, a religion teacher at an Oberschule in Idar- Oberstein. Maus, who was associated with the Confessing Church, was accused of undermining the war effort because he failed to properly manage a class discussion of Jesus’ command to love one’s enemies. He received a two-year sentence and died while being transported to Dachau. Schneider contrasts Maus’ story with that of Reinhold Krause, also an educator, but most famous for his address to members of the German Christian Movement at the Berlin Sport Palace Rally in 1933. Schneider finds that Krause both appropriated and violated aspects of liberal Protestant thought. The cases of Maus and Krause, Schneider argues, call into question both the “conservative decadence model” that blames liberal Protestant theology for Nazi conceptions of Christianity and the “progress- optimistic model” that exonerates it of all charges. Theological orientations, including diverse political theologies in the twentieth century, cannot be judged apart from their historical contexts. Likewise, one should not reduce contemporary religious education to the narrow range of options that were present in the Third Reich, nor should one assume that those options will have the same value in all historical settings.

Two of the chapters are biographical studies of individual religious educators or professors at teacher training institutions. Thomas Martin Schneider’s “Die Umbrüche 1933 und 1945 und die Religionspädagogik” takes up the story of Georg Maus, a religion teacher at an Oberschule in Idar- Oberstein. Maus, who was associated with the Confessing Church, was accused of undermining the war effort because he failed to properly manage a class discussion of Jesus’ command to love one’s enemies. He received a two-year sentence and died while being transported to Dachau. Schneider contrasts Maus’ story with that of Reinhold Krause, also an educator, but most famous for his address to members of the German Christian Movement at the Berlin Sport Palace Rally in 1933. Schneider finds that Krause both appropriated and violated aspects of liberal Protestant thought. The cases of Maus and Krause, Schneider argues, call into question both the “conservative decadence model” that blames liberal Protestant theology for Nazi conceptions of Christianity and the “progress- optimistic model” that exonerates it of all charges. Theological orientations, including diverse political theologies in the twentieth century, cannot be judged apart from their historical contexts. Likewise, one should not reduce contemporary religious education to the narrow range of options that were present in the Third Reich, nor should one assume that those options will have the same value in all historical settings.