Review of Hubert Wolf, Pope and Devil: The Vatican’s Archives and the Third Reich

ACCH Quarterly Vol. 15, No. 3, September 2010

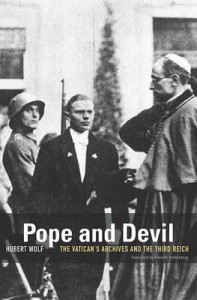

Review of Hubert Wolf, Pope and Devil: The Vatican’s Archives and the Third Reich, translated by Kenneth Kronenberg (Cambridge, Mass. and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), 325 pp. ISBN: 978-0-674-05081-5.

By Heath A. Spencer, Seattle University

In this English translation of Papst und Teufel (first published in 2008), Hubert Wolf successfully challenges the conspiracy theories and sensationalism of a number of playwrights, novelists, journalists, and historians who have assessed the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Nazi state. Remarkably, he does so without letting Catholic leaders off the hook or covering up their very real moral failures. Making use of recently released materials from the Vatican Secret Archives, he has produced a provocative and highly readable account of the “view from Rome” during the turbulent decades between the two world wars, as well as new insights into the way Pope Pius XI and Eugenio Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII) understood, interpreted, and responded to the early stages of a catastrophe that culminated in world war and genocide after 1939.

In this English translation of Papst und Teufel (first published in 2008), Hubert Wolf successfully challenges the conspiracy theories and sensationalism of a number of playwrights, novelists, journalists, and historians who have assessed the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Nazi state. Remarkably, he does so without letting Catholic leaders off the hook or covering up their very real moral failures. Making use of recently released materials from the Vatican Secret Archives, he has produced a provocative and highly readable account of the “view from Rome” during the turbulent decades between the two world wars, as well as new insights into the way Pope Pius XI and Eugenio Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII) understood, interpreted, and responded to the early stages of a catastrophe that culminated in world war and genocide after 1939.

Wolf begins with an analysis of Pacelli as nuncio in Germany from 1917 to 1929. The failure of Benedict XV’s peace appeal in 1917 seems to have convinced Pacelli that direct papal intervention in the Great War (and future conflicts) was ill-advised. Pacelli’s reports from this period also reveal his preoccupation with the ills of modernism (ranging from liberalism and socialism to contraceptives and coeducational sports) and his desire to make state-oriented German Catholic bishops more responsive to Vatican directives. Although Pacelli was anti-democratic and anti-socialist, he was pragmatic enough to recognize the need for the Catholic Center Party to work with the Social Democrats in the Weimar Republic, and although he displayed a level of anti-Semitism that was typical among European Catholics in this era, he strongly condemned the virulent racism of völkisch groups he encountered in Germany during the 1920s.

Wolf follows up with an assessment of attitudes toward Jews and Judaism in the Vatican during the 1920s. Unlike Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, who posits a uniform and essentialist Catholic anti-Semitism, Wolf finds evidence of diverse views ranging from the philo-Semitism of Amici Israel, a Catholic organization promoting Jewish-Christian reconciliation, to the vehemently anti-Jewish orientation of Raffaele Merry del Val, head of the Holy Office under Pius XI. Unfortunately, Pius XI took the side of the Holy Office in a controversy over reform of the Good Friday liturgy, leading to the censure of philo-Semites in the Congregation of Rites and the dissolution of Amici Israel. Pius XI’s famous condemnation of anti-Semitism in 1928 was an attempt to deflect accusations that might emerge when he dissolved a pro-Jewish Catholic organization, as well as a way to distinguish between an “acceptable” Catholic anti-Judaism and racist anti-Semitism. The back story Wolf reveals to Pius XI’s decree is a more nuanced story of moral failure than the one Goldhagen tells, but it still seriously undermines simplistic representations of Pius XI as a courageous opponent of anti-Semitism.

Wolf’s chapter on the Concordat of 1933 challenges the “package-deal thesis” promoted by Klaus Scholder, who suggested that Pacelli, as Papal Secretary of State, pressured German bishops to lift the ban on Catholic membership in the Nazi Party and encouraged the Center Party to support the Enabling Act—both in order to secure passage of a Concordat with the German government. Nuncial reports as well as Pacelli’s notes on meetings with Pius XI and various ambassadors to the Holy See reveal that Pacelli was caught off guard by the German bishops when they announced they were lifting the ban. Wolf argues persuasively that if Pacelli had been pulling the strings, he would have demanded something in return for this concession. Instead, he had to negotiate the Concordat without some of his key bargaining chips.

In the end, both Pius XI and Pacelli made unpalatable compromises in order to preserve the Church’s ability to provide pastoral care under hostile regimes. It was easy for them, as well as the German episcopate, to condemn Nazi ideologues like Alfred Rosenberg, but much harder to openly condemn a head of state—even Adolf Hitler. In such cases, they preferred indirect approaches, refuting ideas that were contrary to Catholic teaching without naming the authors of those ideas. Even in the context of race war and genocide after 1939, Pacelli (by then Pope Pius XII) indicated that he preferred public action by German bishops to direct intervention by the Vatican. When such action was insufficient, Pius XII still considered his own hands tied.

Pope and Devil, by revealing the decision-making processes in the Vatican in such rich detail, presents us with a nuanced story that includes moral successes and failures as well as a large gray zone in between. Wolf’s theological training, ordination, and prior years of experience in the Vatican Archives work to his advantage as he assesses the interplay of individual personalities and institutional dynamics in the Catholic hierarchy. His ability to transmit his scholarship to specialists and non-specialists alike earned him the Communicator Award from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft in 2004, and it continues to play out in his leadership of a critical online edition of Pacelli’s reports to Rome during the latter’s years as nuncio in Germany. Some American readers will be disappointed that Wolf does not do more to engage credible scholarship on this side of the Atlantic, but perhaps his priority was to address readers who are more likely to have heard of figures like Goldhagen, John Cornwell, and Dan Brown—even though such authors make relatively easy targets. In any case, the book is a refreshing contribution to a longstanding but still unresolved debate about the Vatican’s responses to National Socialism, particularly where Pacelli was involved. It will not end the “Pius war,” but by demolishing the most egregious misrepresentations on both sides, it points the way toward more productive discussions in the future.