Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 22, Number 1 (March 2016)

Conference Report: 8th Annual Summer Workshop for Holocaust Scholars, International Institute for Holocaust Research, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, July 6-9, 2015

By Suzanne Brown-Fleming, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum*

The experiences of Christians defined as “non-Aryans” by Nazi and Axis racial laws remain among the most fascinating and under-researched aspects of the Holocaust, not least because this very specific category of Christians, made so by the sacrament of baptism, is sometimes still misunderstood/misrepresented. They are seen as Jews and are (literally) counted as “Jews” rescued or aided by Christian institutions, NGOs, and individuals. In July 2015, the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem organized a workshop for seventeen scholars from eight countries (Austria, Germany, Israel, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Serbia, the United States), to present their work-in-progress and compare their findings on this issue.

Monday, July 6, began with stimulating opening remarks by Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Research and Incumbent of the John Najmann Chair of Holocaust Studies at Yad Vashem, Dan Michman. The first panel focused on Christians defined as non-Aryans by Nazi laws residing in Germany. Assaf Yedidya (Yad Vashem and Efrata College, Israel) presented his research on hundreds of converts from Christianity to Judaism, and their treatment under Nazi law. True to the Nazi racial definition of a Jew as someone with Jewish parents and/or grandparents, a Christian of “Aryan” descent who asked to convert to Judaism was not only permitted to do so, but was shielded from deportation by state authorities on the basis of his or her “Aryan” race credentials. Nor could a religious convert to Judaism who was an “Aryan” marry another (racial) Jew, since this was prohibited by the Nuremberg Laws.

Maria von der Heydt (Centre for Antisemitism Research, Technical University Berlin, Germany) followed with her research on so-called “Geltungsjuden,” defined in Nazi racial law as those born into mixed marriages and who met three conditions: if they belonged to a Jewish religious community after September 1935; if they were married to a Jews; or if they were born out of wedlock to a Jewish mother after July 1936. The number of Germans meeting this set of criteria was small, numbering only about 2,000 in 1943, at which time essentially they were subjected to the same fate as so-called “Mischlinge.”

In a session moving across the Vatican city-state, France, and Romania, Suzanne Brown-Fleming (USHMM) opened with her early findings from Vatican records generated during the key latter half of 1938, when the annexation of Austria, the Italian racial laws, and the Kristallnacht pogrom in Germany drove many Catholics in mixed marriages or who were themselves defined as “non-Aryan” to write to the Vatican for aid and succor. Many of these letters reflected a feeling of belonging neither to the Catholic nor to the Jewish communities. As such letters mounted rapidly in the latter half of 1938, Pope Pius XI contacted the United States National Catholic Welfare Conference to request aid for Catholics impacted by the racial laws and attempting emigration. Internal correspondence between the Vatican and various nunciatures (diplomatic headquarters) around the world revealed a clearly stated lack of willingness to offer help to either practicing or secular Jews.

Eliot Nidam Orvieto (Yad Vashem) followed with a nuanced and fascinating presentation about rescue of Jews, Catholics defined as such by Nazi/Axis racial laws, and so-called “Mischlinge” by the Congregation of Priests of Notre Dame de Sion and their sister community, the Congregation for Religious of Notre Dame de Sion. Founded in the mid-nineteenth century by Jewish converts to Catholicism, both communities were originally founded to seek the conversion of Jews. Nidam Orvieto examined the broader issues of conversion and the motivations for it, the preference given or not given to the baptized, and the way Catholics impacted by the racial laws were treated in the case of Notre Dame de Sion in France.

Ion Popa (Free University Berlin, Germany) discussed the case of Romanian Jews who sought conversion to Roman Catholicism, and attempted to do so in large numbers after 1941 in the hopes for Vatican protection. Describing the bans on conversion in Romania issued in 1938 and 1941 and the fight against these measures by papal nuncio Andrea Cassulo, Popa highlighted the acceptance of the ban against conversation by the Romanian Orthodox Church and the open opposition to it by the Roman Catholic Church. He also described the particular case of Bukovina, where Jews converted in large numbers to a small Evangelical Church before 1940, providing the context of the vicious persecution of Jews in Romania in the 1930s driving such trends.

On Tuesday, July 7, the case of Poland was the focus of three presentations, the first by Rachel Brenner (University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA). Brenner gave a moving presentation on the interwar “intellectual-artistic Polish-Jewish” milieu in Warsaw and rescue efforts by three Polish-Gentile members of this circle: Zofia Nałkowska, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, and Aurelia Wyleżyńska, focusing specifically on the psychological crises, emotional stresses, and intellectual justifications used by the Polish-Gentile diarists under study as their behavior toward friends considered as equals prior to the stresses of the war and Holocaust changed, often not for the better. Katarzyna Person (Jewish Historical Institute Warsaw, Poland) presented her research on the Jewish Order Service in the Warsaw Ghetto, often described in contemporary accounts by other Jews as consisting largely of “converted” or “highly assimilated” Jews. Using lists of members in the Jewish Order Service in Warsaw, Person found that its membership also included orthodox Jews and Jews with strong Zionist backgrounds. Emunah Nachmany Gafny (Independent Scholar, Israel) discussed Jewish children in hiding on the “Aryan side” in Poland, their experiences in formulating a false Christian identity, their reception by Polish Catholics, and their own conflicted feelings as they professed to become part of the Christians community.

A session on Serbia followed. Jovan Ćulibrk (Jasenovac Committee of the Holy Assembly of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church) presented a picture of the small Jewish community in pre-war Yugoslavia, which consisted of the Zagreb Jewish community that in large numbers converted in Roman-Catholicism in 1938; the Sephardi community with its strong identification with the Serbian national cause; and the “new” generation that embraced Zionism. Ćulibrk argued that where one understood oneself–and was understood by others–to fall on this spectrum had a distinct impact on one’s fate. Bojan Djokic (Museum of Genocide Victims, Belgrade, Serbia) presented a list of over 657,000 individuals who died during World War II, some of whom had at least one Jewish parent but are not understood to be “Jewish” victims. Djokic outlined the complex research required to better document which victims were, in fact, of Jewish origin.

Wednesday, July 8, began with a set of presentations on Austria and Germany. Michaela Raggam-Blesch (Austrian Academy of Sciences) focused on the living conditions of those classified as so-called “Halbjuden” (half-Jews) and their parents in so called “Mischehen” (mixed marriages) during the Nazi regime in Austria. With dramatic changes to their situation and status in 1938 with the Anschluss, in 1941 with the introduction of the yellow star, and during the war with the deportations of Jews, the remaining population of Christians defined as Jews by the racial laws could suddenly find themselves in positions of authority in the Jewish Council of Elders, even though they held no religious ties to the Jewish community.

Maximilian Strnad (Ludwigs-Maximilians-University of Munich, Germany) presented his research on the over 12,000 Jews in “privileged” mixed marriages who had been spared deportation and were still living in the so-called Altreich in September 1944. In the final year of the war, the Nazi regime established labor battalions in the Rhineland, Westphalia and Breslau, followed by orders for deportation to Theresienstadt in the spring of 1945. Strnad laid out the internal dynamics within the Nazi regime driving the increasingly radical, though not necessarily successful, policy in the final months of the war.

Geraldien Von Frijtag (Utrecht University, Netherlands) discussed the fascinating case of Hans Georg Calmeyer, the figure within the German administration in the Netherlands authorized to decide upon 5,500 cases of Jews who petitioned for a change in their administrative status from so-called “Volljude” (full Jew) to “Mischling” or non-Jew. Von Frijtag discussed how Calmeyer treated these cases, based on his own background and political inclinations.

Jaap Cohen (NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies) presented a large-scale rescue operation, the Action Portuguesia, set up by a group of Sephardic Jews in the Netherlands in order to evade deportation. The Action Portuguesia formulated an argument that because they were of a different “race” than Ashkenazi Jews, Sephardim should not be regarded as Jews under Nazi and Axis racial law. Cohen examines the precedents, arguments and ultimate fate of this school of thought as espoused by members of the d’Oliveira family.

The final day of the workshop, July 9, began with a presentation by Susanne Urban (International Tracing Service, Bad Arolsen, Germany), who examined the postwar fates of so-called “Halbjuden” and “Mischlinge.” She discussed their own “self-understanding/self-perception” as expressed in their applications to the International Refugee Organization (IRO) for displaced persons (DP) status, and analyzed how IRO officials categorized such applicants. This depended on many factors, including whether they had spent the war years in forced labor, in a concentration camp, or even as draftees into the German Wehrmacht.

Joanna Michlic (University of Bristol, United Kingdom and Brandeis University, United States) presented what she called “atypical” histories of Polish Jewish children during and after the war. The children she studied came from highly culturally assimilated middle-class Jewish families, from ethnically mixed marriages between Polish-Jews and ethnic Poles, and from relationships between Jewish fugitives and their rescuers.

The workshop concluded with two presentations relating to Italy. Valeria Galimi (University of Tuscia, Italy) examined the Italian racial laws of 1938 and how they were understood and implemented by the Mussolini regime and during the Republic of Salò. Especially interesting was her analysis of petitions for exemption in “cases of special merit” (benemerenze particolari), which often contained letters directly to Mussolini reflecting the petitioner’s thoughts on the “Fascist cause” and their own place within it. Maura de Bernart (University of Bologna, Italy) examined the fate of Jews and Christians defined as such in Forlì, culminating in the massacres at the Forlì airport (June to September 1944).

Dina Porat (Chief Historian, Yad Vashem and Tel Aviv University, Israel) offered closing comments, remarking on the difficulties of making any broad generalizations about those Nazi and Axis victims who found themselves defined, in whole or in part, as Jews under the racial laws. Factors included conversion to Christianity (and the date at which it took place), level of implementation at the local level, attitudes of the local population and religious institutions, radicalization of the Nazi and Axis regimes in the face of defeat, and many other influences discussed over the four days of the conference. Workshop participants agreed on the need to continue study of what the organizers called “non-Jewish Jews” at the city/community, regional and national levels, so as to be able to best contextualize these victims within the larger history of the Holocaust.

* The views as expressed are the author’s alone and do not necessarily represent those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

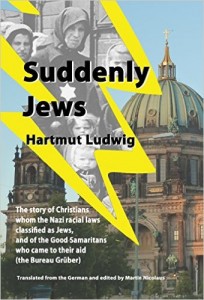

When Hitler came to power in 1933, the majority of German Protestants loyally supported him, believing his promises to restore Germany’s place in the world, and to save them from the danger of Communist revolution. His rabble-rousing attacks on the Jews were dismissed as mere propaganda, which would be abandoned once the regime settled into power. But in fact the Nazis only increased their anti-Semitic campaigns, both by executive decree and by legislation, leading to the vicious outbursts of November 1938, known as the Kristallnacht. Grievously affected were those in the Protestant churches who now found they were classified as Jews on racial grounds, regardless of the fact that they or their parents had converted to Christianity in earlier years. They could expect no help from the pro-Nazi authorities in the majority of Protestant churches. Only in the minority Confessing Church were to be found some men and women who rallied to their support. In the crucial circumstances in later 1938, the Provisional Leadership of the Confessing Church selected a Berlin pastor, Heinrich Grüber, to organize relief efforts for these Protestants of Jewish origin throughout the country. He set up his own independent office, and immediately began to search out opportunities for those affected to emigrate. At the same time, he sought to provide assistance to those who could not or were not willing to leave the country. But in 1940 this assistance was halted by the Gestapo. Grüber’s chief assistant was murdered, along with fourteen other helpers deported to extermination camps. Fortunately, Grüber himself survived and continued his ministry in post-war Berlin.

When Hitler came to power in 1933, the majority of German Protestants loyally supported him, believing his promises to restore Germany’s place in the world, and to save them from the danger of Communist revolution. His rabble-rousing attacks on the Jews were dismissed as mere propaganda, which would be abandoned once the regime settled into power. But in fact the Nazis only increased their anti-Semitic campaigns, both by executive decree and by legislation, leading to the vicious outbursts of November 1938, known as the Kristallnacht. Grievously affected were those in the Protestant churches who now found they were classified as Jews on racial grounds, regardless of the fact that they or their parents had converted to Christianity in earlier years. They could expect no help from the pro-Nazi authorities in the majority of Protestant churches. Only in the minority Confessing Church were to be found some men and women who rallied to their support. In the crucial circumstances in later 1938, the Provisional Leadership of the Confessing Church selected a Berlin pastor, Heinrich Grüber, to organize relief efforts for these Protestants of Jewish origin throughout the country. He set up his own independent office, and immediately began to search out opportunities for those affected to emigrate. At the same time, he sought to provide assistance to those who could not or were not willing to leave the country. But in 1940 this assistance was halted by the Gestapo. Grüber’s chief assistant was murdered, along with fourteen other helpers deported to extermination camps. Fortunately, Grüber himself survived and continued his ministry in post-war Berlin.

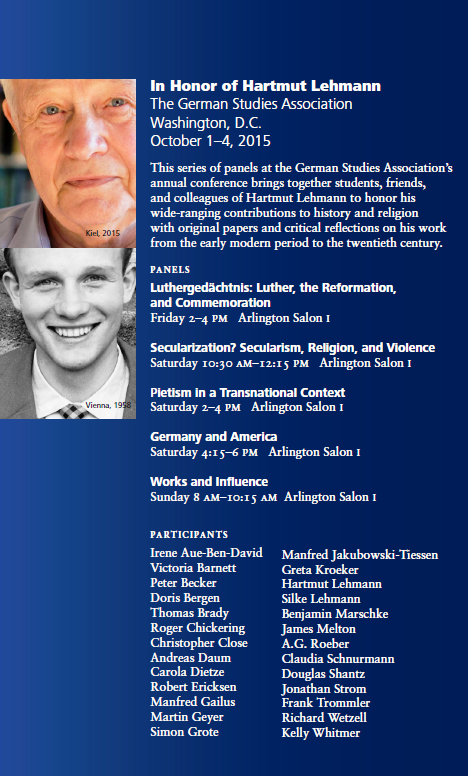

The panel participants began the conference with a dinner to honour Hartmut and his wife, Silke Lehmann. James Harris spoke about Hartmut’s life and career trajectory, emphasizing his close ties to the United States, which began with a high school exchange program and continued through many visiting positions at UCLA, Chicago, Harvard, and Princeton. In 1987 Lehmann became the founding director of the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC, returning to Germany in 1992 to serve as director of the Max Planck Institute for History in Göttingen. He has been professor emeritus at the University of Kiel since 2004, while continuing to visit the United States often, most recently as a visiting professor at Princeton Theological Seminary.

The panel participants began the conference with a dinner to honour Hartmut and his wife, Silke Lehmann. James Harris spoke about Hartmut’s life and career trajectory, emphasizing his close ties to the United States, which began with a high school exchange program and continued through many visiting positions at UCLA, Chicago, Harvard, and Princeton. In 1987 Lehmann became the founding director of the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC, returning to Germany in 1992 to serve as director of the Max Planck Institute for History in Göttingen. He has been professor emeritus at the University of Kiel since 2004, while continuing to visit the United States often, most recently as a visiting professor at Princeton Theological Seminary.