Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 1 (March 2021)

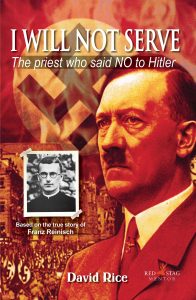

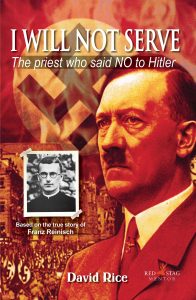

Review of David Rice, I Will Not Serve: The Priest Who Said NO to Hitler (Dublin: Mentor Books, 2018). ISBN: 978-1-912514-04-5.

By Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Simon Fraser University

In the early morning hours of August 21, 1942, Austrian priest Franz Reinisch was executed by the Nazi regime for “subversion of the military force” (a literal translation of the German term Wehrkraftzersetzung). His specific crime was refusing to swear the oath of loyalty required of all German soldiers when called up, which included explicit language about rendering “unconditional obedience to the Leader of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, supreme commander of the armed forces.” Reinisch’s response was not so much pacifism or even conscientious objection, which is a refusal to perform military service (this has not stopped segments representing both groups from claiming him as a hero). He made very clear that he would have willingly served the German people or a different government, and that he believed in the fight against Bolshevism. Rather, he was absolutely unwilling to give an oath of personal loyalty to Hitler, whom he viewed as a monster verging on the Antichrist. As such, he was the only Catholic priest in the Third Reich who refused his call-up order, and the only priest executed for this.[1] Irish journalist David Rice brings us the story of this remarkable, and anomalous, individual.

This is not a typical academic monograph. Students or scholars looking for a rigorous critical examination of Reinisch and his environment, with careful documentation of the evidence, will be disappointed. Rice’s judgment of his subject his balanced – he depicts Reinisch as a flawed human whose strength of will was extraordinary but who also clearly had his faults – but his sympathy for Reinisch is tangible. Rice does not provide consistent citations, though occasionally he will clarify a term or refer to a source for a quotation. His “source books”, listed at the end in (seemingly) random rather than alphabetical order, contain relevant scholarship on Reinisch in both English and German, but is not exhaustive on any given subject, indicates no archival research, and includes references whose impact on the text are unclear. For instance, Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin, Primo Levi’s If This is a Man, and Heinz Höhne’s The Order of the Death’s Head are all mentioned, but do not appear nor are they alluded to in the main text. What scholars are likely to find most problematic, though, is the style in which Rice chooses to write: in an interview with The Irish Examiner, Rice explains, “I didn’t want it to be a history book. I wanted to write it like a film script, so that you could see things happening. I couldn’t be a fly on the wall, but I tried to get inside the protagonist’s head, and I took on Joyce’s and Proust’s stream of consciousness.”[2] Thus much of the book is either conversational, as Rice reconstructs exchanges that Reinisch allegedly had with family members, friends, other priests, and representatives of the Nazi regime, or introspective, as Rice attempts to convey Reinisch’s mental state and thought processes about Nazism and his decision to refuse the oath. The dialogue, delivered in present tense, can be doubly jarring for the historian, both for its intended emotional resonance as well as for its unconventionality. Studies that claim to be “based on historical fact and painstakingly researched” (back cover) simply do not usually include the following kind of verse:

This is not a typical academic monograph. Students or scholars looking for a rigorous critical examination of Reinisch and his environment, with careful documentation of the evidence, will be disappointed. Rice’s judgment of his subject his balanced – he depicts Reinisch as a flawed human whose strength of will was extraordinary but who also clearly had his faults – but his sympathy for Reinisch is tangible. Rice does not provide consistent citations, though occasionally he will clarify a term or refer to a source for a quotation. His “source books”, listed at the end in (seemingly) random rather than alphabetical order, contain relevant scholarship on Reinisch in both English and German, but is not exhaustive on any given subject, indicates no archival research, and includes references whose impact on the text are unclear. For instance, Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin, Primo Levi’s If This is a Man, and Heinz Höhne’s The Order of the Death’s Head are all mentioned, but do not appear nor are they alluded to in the main text. What scholars are likely to find most problematic, though, is the style in which Rice chooses to write: in an interview with The Irish Examiner, Rice explains, “I didn’t want it to be a history book. I wanted to write it like a film script, so that you could see things happening. I couldn’t be a fly on the wall, but I tried to get inside the protagonist’s head, and I took on Joyce’s and Proust’s stream of consciousness.”[2] Thus much of the book is either conversational, as Rice reconstructs exchanges that Reinisch allegedly had with family members, friends, other priests, and representatives of the Nazi regime, or introspective, as Rice attempts to convey Reinisch’s mental state and thought processes about Nazism and his decision to refuse the oath. The dialogue, delivered in present tense, can be doubly jarring for the historian, both for its intended emotional resonance as well as for its unconventionality. Studies that claim to be “based on historical fact and painstakingly researched” (back cover) simply do not usually include the following kind of verse:

‘But here’s the thing you must remember: your Church – my Church, indeed (I’m a Catholic myself) – has not spoken against military service. And more than that, the attitude of your superiors flatly contradicts yours. Their wish and orders are for you to serve. Can you go against that?’

‘That’s what bothers me the most -’

‘You’ve got to keep in mind the interests of the Church itself, of your order, indeed of your family. They’ll all be terribly damaged by your refusing the oath. And by your execution, which will certainly follow.’

‘I’m aware that I am going to be shot for this -’

‘I hate to have to tell you, Father, that you’re not going to be shot.’

‘I’m not -?’

‘Shooting is for soldiers. You’re going to be beheaded. You see, you’ll be a criminal, not a soldier. I’m afraid it’s the Fallbeil for you – the guillotine.’

Franz stares at him. Then, with a hand to his mouth, he lurches towards the open window and vomits. And vomits until there is nothing left to vomit. (215-216; emphasis in original)

The passage is vivid, the dilemma stark, the protagonist immediately sympathetic. But for the reviewer, considering the author’s explicit intentions and the book’s format and style, it is difficult to know which standards to apply. I Will Not Serve might be treated as a piece of investigative journalism by an award-winning and acclaimed journalist and author; it might also be judged historical fiction or fictionalized history, depending on the reviewer’s perspective and mood. The WorldCat database categorizes it under “World War, 1939-1945 – Religious Aspects – Catholic Church” and “Reinisch, Franz”, indicating its important historical and biographical dimensions. I will scrutinize the book according to two measures: the historical accuracy of the text itself, and the utility of trying “to get inside [Reinisch’s] head” for readers interested in religious history (and this newsletter).

In his interview with the Irish Examiner, Rice mentions his background in German (Languages and Literature), which enabled him to translate material by and about Reinisch that he received from “an order” in “a diocese in Germany.” He does not provide either name, but one might assume the diocese to be Trier, where Schönstatt is located – although Reinisch was a Pallottine priest who was ordained in Innsbruck, he was also a member of the Schönstatt apostolic movement founded by Pallottine priest, and mentor of Reinisch, Josef Kentenich (who would himself survive three years in Dachau). Rice declares, “Reinisch took to the Schönstatt spirituality as if he were born to it” (92). Thus the reader can assume the author’s access to personal documentation written by Reinisch himself, including his diaries, but is left to wonder exactly which excerpts are drawn from this documentation, which ones Rice has embellished, and which are more or less inferred or fabricated. Establishing historical accuracy insofar as Reinisch’s statements are concerned is thus a frustrating enterprise. On the grander brushstrokes of biographical and historical context – Reinisch’s early life and family in the Tyrol, the history of Nazism, the history of the Pallottines, Father Kentenich and the Schönstatter movement – Rice treads more stable ground, if only because he stays close to what scholars accept as common knowledge. Reinisch had a wild spell as a young man before deciding on the priesthood. He suffered from regular bouts of ill health. He doubted his vocation on more than one occasion and gave forceful, opinionated sermons that likely played a role in his frequent transfers from diocese to diocese in both Austria and Germany. Long before the 1938 Anschluss he was a convinced and open opponent of Nazism and its leader, to whom he referred more than once as the “shit-brown Führer.” At a conference in Mannheim in December 1935, he reminded his listeners, “The Jesus on [the] cross is the world’s great apostle, who lived and bled for all the world. For all the world, I say. He died for all, and that includes the Jews” (107; emphasis in original). In Salzburg in early 1937, in another sermon, he said, “Satan is loose in Germany. I know. I’ve been there and I’ve seen it” (128). In 1940 the Gestapo formally forbade him from preaching.

Beyond these brushstrokes, the critical reader will have trouble determining what to trust as authentic. Rice relates a conversation as early as 1925 between Reinisch and another of his priestly mentors, his “de facto spiritual director” Richard Weickgenannt, responsible for interesting Reinisch in the Pallottines. When Weickgenannt brings up the subject of Hitler and Nazi racism, Reinisch replies, “Anyhow the churches would take a stand against such nonsense, wouldn’t they? I mean, Jesus was a Jew, wasn’t he?” (55) When Weickgennant argues, justifiably, that antisemitism in the Catholic Church was much broader and ongoing than a few “bigoted individuals” (56 – Rice puts these words in Reinisch’s mouth), Reinisch is initially affronted. That Reinisch had a quick temper is apparent in other biographies, and that the Catholic Church has a long history of anti-Jewish and antisemitic beliefs and behaviours is incontrovertible. But here one wonders exactly what the documentation shows and what Rice has invented to illustrate that quick temper as well as Church history: did Reinisch speak so explicitly as early as the mid-1920s on the subject? Was he an unusual enough Catholic to defend Jesus’s Jewish origins but not astute enough to recognize the antisemitism in his own church?

Later in the text Reinisch encounters a friend of his from childhood, Anton Loidl, who chose to fall in with the Nazi regime and became a member of the SS-Einsatzgruppen. In mid-October 1941, he seeks out Reinisch while on leave and confesses his crimes, delineating in some detail his involvement in the mass shooting of Jewish men, women, and children on the Eastern Front. He asks Reinisch for forgiveness, as a penitent to a priest, but Reinisch refuses out of disgust and horror: “You’re a child of Satan. You – are – evil. Like Cain, you’re accursed on this earth. He only killed one – you’ve slaughtered hundreds – thousands by now. You are cursed beyond redemption.” He changes his mind the next day, but only after the intercession of a nun. We are told that Loidl transferred to the Wehrmacht and was later killed in battle (192-193; emphasis in original).

Again, the passage mixes the verifiable with the unverifiable: it is not incredulous that Reinisch might have known someone who was involved in mass shooting; the ranks of the Einsatzgruppen, who had been formed by Reinhard Heydrich in the aftermath of the Anschluss, were filled with Austrians. Nor is it unlikely that priests, both serving as chaplains with the Wehrmacht as well as stationed in parishes on the home front, might have heard confessions that included admissions of responsibility for participating in atrocities and war crimes, though the seal of the confessional prevents us as scholars from knowing definitively what these confessions might have contained, what penance was given, whether absolution was granted. What we cannot authenticate is Rice’s presentation: that Reinisch knew someone personally in the Einsatzgruppen, that that person confessed to him about his role in mass shootings, that Reinisch reacted by withholding absolution citing a lack of true remorse (but also, his temper). Perhaps Rice found notes about this encounter in Reinisch’s diary but he does not relay this to his audience. Rice gives us a full name – Anton Loidl – so it seems unlikely that he would have fabricated an individual and given him such a story.[3] But considering his explication about getting into Reinisch’s head, and of writing Reinisch’s story more like a film than like a history text, the reviewer is left to conclude that Rice may have exaggerated some or most of an actual incident to make for a more dramatic scene in which Reinisch learns of the genocide and has to decide how to act, as a human but also as a priest, vis-à-vis a perpetrator.

Many of the dialogic passages will lead readers to these same questions. So one will have to decide to what extent these passages render the book untrustworthy in its entirety. Initially I was inclined to treat I Will Not Serve as a half-step removed from historical fiction: Rice cites his sources, but does not convey how he has used them, and has, quite literally, put words into the mouths of his subjects. But as I began to construct the review I was reminded of another book that I taught in a class last semester, and the controversy it aroused when a historian dared to embark on a somewhat similar enterprise. Natalie Zemon Davis published The Return of Martin Guerre in 1983, a story about the trial of an imposter in sixteenth-century France that centers significantly on the imposter’s wife: what she knew, when she knew it, whether she played a role in the imposter’s deception. Zemon Davis candidly recounted in the introduction that, where her sources fell short in preserving evidence about her subjects, “I did my best through other sources from the period and place to discover the world they would have seen and the reactions they might have had. What I offer you here is in part my invention.”[4] When the book instigated considerable controversy about her methodology, leading another historian to charge her with fabrication and anachronism, she responded, “my whole book… is an exploration of the problem of truth and doubt…. ‘In historical writing, where does reconstruction stop and invention begin?’ is precisely the question I hoped readers would ask and reflect on.”[5]

The comparison is not entirely without friction: Rice’s “stream of consciousness” is not quite at the level of Zemon Davis’s studied inventions. She is a trained historian and was both thorough and rigorous in her explanation of sources, where she found them, and how she used them; Rice is a journalist (he also holds a degree in sociology) and, as already explained, he lists his sources but otherwise gives no indication as to how he has used them, and does not mention at all the primary-source documentation he received about Reinisch in Germany. Zemon Davis does not recount conversations in her text, though she sometimes speculates about what might have been said between the protagonists or how the trial unfolded (she had different accounts of the trial on which to base this speculation). Most of Rice’s chapters are centered around dialogue, either between Reinisch and another person, or within Reinisch himself, relaying his considerable struggle to reconcile himself with the ramifications of abjuring the oath. Likely Rice has evidence of this internal conflict since he was able to use Reinisch’s personal papers, which almost certainly included such indications. But again, the reader does not know for certain.

Beyond these significant concerns, a reviewer might take issue with other, more minor aspects of the book. Rice begins each chapter with an epigraph, most of which are about conscience, from sources ranging widely from Hermann Göring to Mahatma Gandhi. None are cited, nor are sources for the epigraphs clearly listed in his source list. The cover is also awkward, featuring a small black-and-white photo of Reinisch (which we learn in the text is undated, but likely from his last years before he was arrested and executed) that is dominated by a larger photo of Hitler in his later years, a swastika in the background, in red and yellow tones. Cover designs are usually decided by the publisher, but surely the author might have pointed out the irony that Reinisch, the subject about whom he’s written so meaningfully, is literally dwarfed by Hitler, the man who Reinisch believed was a criminal and even the personification of evil, and the reason that Reinisch was executed.

So there is a lot in this book that should concern a careful, critical reader searching for historical evidence about Franz Reinisch. Perhaps a casual reading attitude is more appropriate to fully appreciate the text. In my opinion, however, even the critical reader should consider Rice’s contribution to the growing literature about Reinisch carefully. To this point it is the only book-length treatment in English of Reinisch. This is also a labour of personal passion. In his interviews with various Irish press outlets, Rice is clearly inspired by Reinisch’s commitment to his conscience even when most of his world was against him (the Pallottines threatened to expel him if he did not recant his refusal to swear the oath; one of his last acts before his execution, as Rice relates, was to encourage the Father Provincial to do this to save anyone from guilt by association – the letter is printed seemingly in its entirety on p. 260-261). His conscientious delineation of Reinisch’s spirituality, and of the way his beliefs formed and transformed him over a period of several years, contains both important historical notes about different faith movements in Germany and Reinisch’s role in them, notably the Schönstatter movement, as well as the portrayal of an extraordinary individual’s commitment to faith and to his conscience.[6] It is a powerful portrait of one of the Catholic Church’s true martyrs, a German spiritual leader (one of the very few) who took a public stand against Nazism, and paid for it with his life. Reinisch himself deserves broader recognition beyond Germany, particularly as the process of his canonization is ongoing,[7] and Rice’s contribution is likely to facilitate that recognition.

Notes:

[1] My earlier research on Catholics who refused military service found very few examples of conscientious objection, under which I included Franz Reinisch; he was the only priest who refused, although there were at least two other members of lay religious communities. For a complete list, see Faulkner Rossi, Wehrmacht Priests: Catholicism and the Nazi War of Annihilation (Harvard University Press, 2015), pg. 114 n5 and pg. 252.

[2] Sue Leonard, “The priest whose faith decided his fate: execution by the Nazis” (interview with David Rice) in The Irish Examiner, September 8, 2018, https://www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/arid-30867560.html#:~:text=David%20Rice%2C%20whose%20book%2C%20I,align%20himself%20with%20the%20Nazis (last accessed March 2, 2021).

[3] Pandemic-related restrictions and closures prohibited me from trying to document Anton Loidl in written sources; I could unearth nothing about him online. These restrictions also prevented me from accessing German-language biographies of Reinisch, available to me only through interlibrary loan, which is operating but on a much reduced basis. So I could not cross-reference Loidl there, either.

[4] Natalie Zemon Davis, The Return of Martin Guerre (Harvard University Press, 1983), 5. Emphasis added.

[5] Natalie Zemon Davis, “On the Lame”, part of the AHR Forum: The Return of Martin Guerre, in The American Historical Review 93/3 (June 1988), 572.

[6] In this manner Reinisch provokes comparisons with another Catholic Austrian who was executed for his refusal to answer his military service call-up: Franz Jägerstätter, who identified Reinisch as a role model and was executed in 1943. I reviewed a recent film about Jägerstätter, A Hidden Life, in the September 2020 issue of Contemporary Church History Quarterly.

[7] The beatification process, the first step towards canonization, began in April 2013 and was concluded in June 2019. I have been unable to find any current updates about the next stage. Knowing this as I read the book, the remark in Rice’s book that Reinisch allegedly makes during his last meeting with the Tegel prison chaplain, Heinrich Kreutzberg, less than two weeks before his execution, is particularly ironic: “Don’t you try to make a saint out of me!” (260)

This is not a typical academic monograph. Students or scholars looking for a rigorous critical examination of Reinisch and his environment, with careful documentation of the evidence, will be disappointed. Rice’s judgment of his subject his balanced – he depicts Reinisch as a flawed human whose strength of will was extraordinary but who also clearly had his faults – but his sympathy for Reinisch is tangible. Rice does not provide consistent citations, though occasionally he will clarify a term or refer to a source for a quotation. His “source books”, listed at the end in (seemingly) random rather than alphabetical order, contain relevant scholarship on Reinisch in both English and German, but is not exhaustive on any given subject, indicates no archival research, and includes references whose impact on the text are unclear. For instance, Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin, Primo Levi’s If This is a Man, and Heinz Höhne’s The Order of the Death’s Head are all mentioned, but do not appear nor are they alluded to in the main text. What scholars are likely to find most problematic, though, is the style in which Rice chooses to write: in an interview with The Irish Examiner, Rice explains, “I didn’t want it to be a history book. I wanted to write it like a film script, so that you could see things happening. I couldn’t be a fly on the wall, but I tried to get inside the protagonist’s head, and I took on Joyce’s and Proust’s stream of consciousness.”

This is not a typical academic monograph. Students or scholars looking for a rigorous critical examination of Reinisch and his environment, with careful documentation of the evidence, will be disappointed. Rice’s judgment of his subject his balanced – he depicts Reinisch as a flawed human whose strength of will was extraordinary but who also clearly had his faults – but his sympathy for Reinisch is tangible. Rice does not provide consistent citations, though occasionally he will clarify a term or refer to a source for a quotation. His “source books”, listed at the end in (seemingly) random rather than alphabetical order, contain relevant scholarship on Reinisch in both English and German, but is not exhaustive on any given subject, indicates no archival research, and includes references whose impact on the text are unclear. For instance, Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin, Primo Levi’s If This is a Man, and Heinz Höhne’s The Order of the Death’s Head are all mentioned, but do not appear nor are they alluded to in the main text. What scholars are likely to find most problematic, though, is the style in which Rice chooses to write: in an interview with The Irish Examiner, Rice explains, “I didn’t want it to be a history book. I wanted to write it like a film script, so that you could see things happening. I couldn’t be a fly on the wall, but I tried to get inside the protagonist’s head, and I took on Joyce’s and Proust’s stream of consciousness.” Malick is an atypical American director: he has protected his private life to the point of reclusiveness; his projects routinely consume several years; while he has made several critically-acclaimed films (his first film, Badlands; The Thin Red Line, about the Vietnam War; The Tree of Life, about immortality), he is both lauded and criticized for favouring themes and visual aesthetics over plot and narrative (see The Tree of Life). In fact, A Hidden Life delivers a more linear narrative than many of his films, with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end. It opens with Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, the famous aerial shot of clouds and a city gradually coalescing through the mist. Lasting only the first couple of minutes, and including splices from elsewhere in that famous 1934 documentary, such as the stunning panorama of the Nazi Party’s rally grounds, this is all Malick gives to the audience of Hitler’s climb to power and takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia before plunging directly into the fall of 1939. Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) is married to Franziscka (“Fani”, Valerie Pachner), and has two small blonde-haired, blue-eyed daughters. They live in the Upper Austrian village of Sankt Radegund, not far from the German border (Bavaria). We watch them pause in their labour as unseen planes fly overhead, our only clue that the war has begun.

Malick is an atypical American director: he has protected his private life to the point of reclusiveness; his projects routinely consume several years; while he has made several critically-acclaimed films (his first film, Badlands; The Thin Red Line, about the Vietnam War; The Tree of Life, about immortality), he is both lauded and criticized for favouring themes and visual aesthetics over plot and narrative (see The Tree of Life). In fact, A Hidden Life delivers a more linear narrative than many of his films, with an identifiable beginning, middle, and end. It opens with Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, the famous aerial shot of clouds and a city gradually coalescing through the mist. Lasting only the first couple of minutes, and including splices from elsewhere in that famous 1934 documentary, such as the stunning panorama of the Nazi Party’s rally grounds, this is all Malick gives to the audience of Hitler’s climb to power and takeover of Austria and Czechoslovakia before plunging directly into the fall of 1939. Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl) is married to Franziscka (“Fani”, Valerie Pachner), and has two small blonde-haired, blue-eyed daughters. They live in the Upper Austrian village of Sankt Radegund, not far from the German border (Bavaria). We watch them pause in their labour as unseen planes fly overhead, our only clue that the war has begun. The editors, Maria Anna Zumholz and Michael Hirschfeld, discuss significant forthcoming works on both von Faulhaber and Jaeger to account partly for the brevity of the studies here (13). And while there is a detailed chapter by Raphael Hülsbömer on Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli – later Pope Pius XII – and his relations with the German bishops, there is no attempt to integrate the episcopate into Vatican politics or consider the complicated, at times strained relationship between the wartime pope and the bishops as a collective. The editors justify this in part by referencing the closed archives covering the wartime pontificate of Pius XII; they could not have known that the year following this volume’s publication, the Vatican would finally announce the much-anticipated opening of these “secret archives” in 2020.

The editors, Maria Anna Zumholz and Michael Hirschfeld, discuss significant forthcoming works on both von Faulhaber and Jaeger to account partly for the brevity of the studies here (13). And while there is a detailed chapter by Raphael Hülsbömer on Vatican Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli – later Pope Pius XII – and his relations with the German bishops, there is no attempt to integrate the episcopate into Vatican politics or consider the complicated, at times strained relationship between the wartime pope and the bishops as a collective. The editors justify this in part by referencing the closed archives covering the wartime pontificate of Pius XII; they could not have known that the year following this volume’s publication, the Vatican would finally announce the much-anticipated opening of these “secret archives” in 2020. Röw’s intentions are to deliver a comprehensive structural and experiential history of Catholic military pastoral care in Germany, with a particular emphasis on providing a systematic study of chaplaincy (12). He has oriented himself solidly in the available historiography on the subject in both German and English and his archival research is impressively broad, gathering material from four archdiocesan archives (including Salzburg), eight diocesan archives (including one in Austria and one in the Netherlands), and several other state and private collections in Germany. His main source for primary documentation is the Archive of the Catholic Military Bishop, in Berlin, notably the Georg Werthmann collection. Until relatively recently, this rich compilation of chaplaincy-related material, produced by the man who served as second-in-command of the Catholic chaplaincy during the Second World War, was strikingly understudied; in the past four years, three books have appeared whose authors have extensively mined its records.

Röw’s intentions are to deliver a comprehensive structural and experiential history of Catholic military pastoral care in Germany, with a particular emphasis on providing a systematic study of chaplaincy (12). He has oriented himself solidly in the available historiography on the subject in both German and English and his archival research is impressively broad, gathering material from four archdiocesan archives (including Salzburg), eight diocesan archives (including one in Austria and one in the Netherlands), and several other state and private collections in Germany. His main source for primary documentation is the Archive of the Catholic Military Bishop, in Berlin, notably the Georg Werthmann collection. Until relatively recently, this rich compilation of chaplaincy-related material, produced by the man who served as second-in-command of the Catholic chaplaincy during the Second World War, was strikingly understudied; in the past four years, three books have appeared whose authors have extensively mined its records. Pollard has an imposing pedigree, which one might demand of a scholar willing to tackle such a contentious subject: he is no amateur in examining modern popes in times of conflict. He has devoted much of his professional career to the Vatican and Catholicism in Fascist Italy, and his biography of Benedict XV is one of the most significant of any language. His introduction includes several crucial definitions and a brief sketch of the papacy up to Benedict’s election in September 1914. His conclusion speaks cogently of the legacy of the period as a whole, which he refers to simply as the age of totalitarianism, and addresses its greatest legacy: bringing the divisions between Church conservatives and liberals to the fore, leading to the most radical changes in Church history at the Second Vatican Council (478).

Pollard has an imposing pedigree, which one might demand of a scholar willing to tackle such a contentious subject: he is no amateur in examining modern popes in times of conflict. He has devoted much of his professional career to the Vatican and Catholicism in Fascist Italy, and his biography of Benedict XV is one of the most significant of any language. His introduction includes several crucial definitions and a brief sketch of the papacy up to Benedict’s election in September 1914. His conclusion speaks cogently of the legacy of the period as a whole, which he refers to simply as the age of totalitarianism, and addresses its greatest legacy: bringing the divisions between Church conservatives and liberals to the fore, leading to the most radical changes in Church history at the Second Vatican Council (478).