Review of Ulrich Peter, Lutherrose und Hakenkreuz. Die Deutschen Christen und der Bund der nationalsozialistischen Pastoren in der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche Mecklenburgs

Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 4 (December 2021)

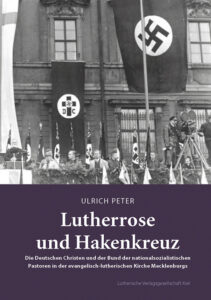

Review of Ulrich Peter, Lutherrose und Hakenkreuz. Die Deutschen Christen und der Bund der nationalsozialistischen Pastoren in der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche Mecklenburgs (Kiel: Lutherische Verlagsanstalt, 2020). 607 pages. ISBN 978-3-87503-266-6.

By Dirk Schuster, University of Vienna / Danube University Krems

Church struggle (Kirchenkampf) is a term that has shaped church historiography since the end of the Second World War. It is still partly subject to instrumentalization today: The Confessing Church (Bekennende Kirche) is characterized positively, often even as an opponent of Nazi ideology against the German Christians. For a long time, there was no further in-depth research into the German Christians beyond this assumption, because the theologically influenced church historiography preferred to turn to the supposed “heroes” of the Confessing Church for historical information. Fortunately, many research projects have emerged in the last few decades, such as the work of Robert P. Ericksen, Susannah Heschel, Doris L. Bergen, Manfred Gailus, Kyle Jantzen, and many more. These researchers have not only studied German Christians and their racist and anti-Semitic notions but have also established a completely new image of the “church struggle,” some going so far as to “deconstruct” the image of a heroic Confessing Church.

Above all, the work on the Thuringian German Christians, the dominant German-Christian movement in the “Third Reich” up to 1945 (Clemens Vollnhals), clearly shows how a large number of evangelical pastors–also far beyond Thuringia–dealt with National Socialism, perceiving it as connected to or at least instrumental in helping to build a “new Germany.” It is particularly striking, however, how many pastors–here again, beyond the Thuringian German Christians–welcomed the anti-Semitism of the National Socialists and even justified it theologically.

Above all, the work on the Thuringian German Christians, the dominant German-Christian movement in the “Third Reich” up to 1945 (Clemens Vollnhals), clearly shows how a large number of evangelical pastors–also far beyond Thuringia–dealt with National Socialism, perceiving it as connected to or at least instrumental in helping to build a “new Germany.” It is particularly striking, however, how many pastors–here again, beyond the Thuringian German Christians–welcomed the anti-Semitism of the National Socialists and even justified it theologically.

In the research on the German Christians, however, there has always been a blank spot that has been pointed repeatedly: whenever the Thuringian German Christians were mentioned as the most powerful group of the German Christians, one reads again and again that, in addition to the complete control of the Thuringian regional church, they could also rely on their sister organization in Mecklenburg because the German Christians also controlled that entire regional church. However, and this must be clearly stated, next to nothing was known about the conditions in Mecklenburg, the prehistory, the period between 1933 and 1945, or even the post-war history apart from individual biographical studies.

Ulrich Peter, who has been dealing with the history of the Protestant Church in Mecklenburg during the Nazi period (alongside his work on the “Religious Socialists”) for a long time, has now presented an overall study that tries to close this large gap–and does it completely. With his historiographical study, Peter provides a fundamental work that is an indispensable addition to further research on church history. Peter consults all the sources available to him: reports from various regional and national archives, papers, publications, etc.

In addition to the strictly chronological presentation of the events between 1933 and 1945 and an overview of the time after 1945 (p. 446–464), it is above all the first part of the book that, from the reviewer’s point of view, makes the developments in Mecklenburg clearly understandable. Since Peter does not begin his study with the founding of the German-Christian movement, the Bund für Deutsche Kirche or the German Christians, but with the structure and theological self-image of the regional church before the First World War, the developments of the 1920s can clearly be understood. This is, for example, the big difference between his work and Oliver Arnhold’s book on the Thuringian German Christians. Peter describes and contextualizes the prehistory on which the developments from 1933 onwards were based. For instance, in a separate subchapter, he makes it clear that long before 1933, even before 1914, anti-Semitism was virulent in the regional church. Another example is the attitude of Regional Bishop Rendtorff (also one of those alleged heroes of apologetic church historiography) and his statements in favor of National Socialism at the beginning of the 1930s.

The subsequent chapter examines in detail the disputes within the church and the increasing influence of the German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), which ultimately found itself directly dependent on Bishop Schulz. It becomes clear that although the German Christian Church Movement increasingly dominated the regional church, they did not have an organizational or even financial basis. Fake membership numbers and disastrous financial behavior at the expense of the regional church characterized the German Christian Church Movement in Mecklenburg.

With his study, Ulrich Peter provides for the first time a detailed insight into the structure, thinking and connections of that regional church. He has completely succeeded in closing the research gap. Lutherrose und Hakenkreuz deserves to be included among the canonical works on church history during the “Third Reich” on which further research will be based.