Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 1 (March 2021)

Public Lecture: “‘The Church is not Afraid of History’: The Opening of the Vatican Archives, 1939-1958”

By: Suzanne Brown-Fleming, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

This lecture, the Hal Israel Endowed Online Lecture in Jewish-Catholic Relations, was delivered for Georgetown University’s Center for Jewish Civilization on November 5, 2020.

Before we begin, I would like to note for the record that the views expressed in this lecture are mine alone and do not necessarily represent those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum or any other organization. It is such an honor and pleasure to be invited by the Center for Jewish Civilization at Georgetown University to deliver the Hal Israel Endowed Lecture in Jewish-Catholic Relations. I especially want to thank Dr. Anna Sommer Schneider, Associate Director for the Center for Jewish Civilization. I have had the pleasure of knowing Dr. Schneider since we met at an important conference on antisemitism held at Indiana University over a decade ago and I know a kindred spirit when I see one!

I am going to start my comments today in the summer of 1996. As a blissfully naïve late-twenty-something Ph.D. candidate in modern German History at the University of Maryland, I had finally landed on a dissertation topic and had arrived at the Catholic University’s Archives in Washington, D.C. I had learned that Catholic University housed the personal papers of Cardinal Aloisius Muench. American-born Cardinal Muench was the most powerful American Catholic figure and influential Vatican representative in occupied Germany and subsequent West Germany between 1946 and 1959. Cardinal Muench held the diplomatic positions of apostolic visitor, then regent, and finally Pope Pius XII’s nuncio, or papal diplomat to Germany. I was delighted to have access to his personal papers, for the personal papers of papal diplomats are typically held in the Vatican’s own archives in Rome. In one of those accidents of history, Cardinal Muench had shipped the bulk of his papers to the United States so that a young American priest could utilize them to write a biography of the cardinal. Happily for me, his papers stayed in America, and so I arrived on my first day, put on my white gloves, and requested the collection. I came across 1957 correspondence between Cardinal Muench and Monsignor Joseph Adams of Chicago. Muench was describing his most recent audience with Pope Pius XII on a spring day in Rome. Muench and Pius were close, bonded by their ties to and love of Germany and its people. They were at ease with one another and, by the time of this audience, had worked together for over 11 years. In this particular May 1957 audience, the pope – and I’m quoting now – told Muench […a] “story…with a great deal of delight.” I continue to quote here: “Hitler died and somehow got into heaven. There, he met the Old Testament prophet Moses. Hitler apologized to Moses for his treatment of the European Jews. Moses replied that such things were forgiven and forgotten here in heaven. Hitler [was] relieved,” continued the pope, and “said to Moses that he [Hitler] always wished to meet [Moses] in order to ask him an important question. Did Moses set fire to the burning bush?” Let me stop here and explain the two references in the “joke.” The pope was making an equivalency between two historical events. The first: the Jewish prophet Moses’ arbitration of the Ten Commandments to the Jewish people after an angel of God appeared to him in a burning bush. The second: Hitler’s rumored involvement in the 1933 Reichstag (parliament) fire, an event that facilitated consolidation of Hitler’s dictatorial powers. Muench closed his letter to Monsignor Adams with this line: “Our Holy Father told me the story with a big laugh.”

So here I was, feeling dumbfounded among other things. The “delight” and “laughter” described by Cardinal Muench indicated to me that neither he nor the pope appeared to understand the inappropriateness of telling a joke relating to the murder of six million European Jews. To my eyes, this exchange between them – one a prince of the church and the other in the chair of Saint Peter as God’s representative on earth for faithful Catholics like myself – demonstrated that neither placed much importance on the Jewish experience under National Socialism. Some might say it captures the failure of the institutional Roman Catholic Church to undertake a strong and public position of sensitivity, respect, and positive action vis-à-vis Jews and Judaism during the papacy of Pius XII.

But what could be carefully researched was limited by the fact that at that time (the late 1990’s), the full archives of Pius XII were still closed. No longer. On March 2, 2020, these archives fully opened. Announced by Pope Francis on March 4, 2019, on the 80th anniversary of the election of Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli (Pope Pius XII) to the office of pope, these new archives consist of an estimated 16 million pages in dozens of languages, spread across multiple archives in Rome and Vatican City. In an ironic twist of history, the much-anticipated archives had to close after four days due to the COVID 19 pandemic. They reopened in early June, and, considering normally scheduled summer closures in July and August, researchers have so far had less than 90 days in the archives. Today I will reflect on their early research findings and the meaning of the archives for Christian-Jewish relations.

The church is complex and so are its archives. Nor are the archives that opened this year completely new. Important but incomplete documentation has been available beginning in 1965 as part of the published series Acts and Documents of the Holy See Relative to the Second World War. Also already available are archives from the pontificate of Pius XI, available in full since 2006, and those of the Vatican Office of Information for Prisoners of War, available since 2004.

For scholars of the churches during World War II, the Holocaust, and the postwar period, we are witnessing an exciting moment. I’m going to first talk about findings in the archives from the perspective of what we learned this last decade from the archives covering the years 1922 to 1939. I will then move to preliminary early findings that have begun to appear since last March.

No modern pope has been as scrutinized as Eugenio Pacelli, Pope Pius XII. Soft spoken, aristocratic, and trained in law and diplomacy, scholars have only been able to study Pius XII through Vatican documents up to 1939 (the date of the end of Pius XI’s reign). Sometimes called “Il Papa Tedesco” (the German Pope) Pius XII was enormously popular with the German people during his time as papal diplomat to Germany from 1917-1929. From 1930 to 1939, he served Achille Ratti, Pope Pius XI, as Secretary of State, the second most powerful position in the Vatican hierarchy. When he became pope in 1939, he controlled the worldwide Catholic Church and the tens of millions of Catholics in a Europe on the brink of war.

Portions of the Vatican’s archival record for the 1922-1939 period are available at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. With thousands of archival pages at my disposal in the Museum’s reading room, three growing children and a full-time job, I decided to approach the material by looking at two key events in Holocaust history: the response of the Vatican and the German Catholic church to the first anti-Jewish laws in 1933 and to the Night of Broken Glass pogrom in 1938. My detailed findings are published elsewhere. Here, let me try to capture some highlights. Let us go back to March 1933. On March 23, 1933, the German parliament passed the so-called “Enabling Law,” abolishing democracy and the constitutional state in Germany. For our purposes, of especial interest is the statement German Chancellor Adolf Hitler made, promising to “respect all treaties between the Churches and the states” and that the “rights” of the Churches would “not be infringed upon.” In response, on March 28, the German Catholic Bishops’ Conference seated in the city of Fulda removed the current ban on Catholic membership in the Nazi Party. On the same day that the Fulda Bishops’ Conference reversed the ban on Nazi Party membership for German Catholics, the Nazi party leadership ordered a boycott, to begin on April 1, at 10 a.m., directed against Jewish businesses and department stores, lawyers, and physicians. A second discriminatory law swiftly followed. On April 7, the passage of the so-called Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service contained the so-called Arierparagraph, stipulating that only those of Aryan descent could be employed in public service. State-sponsored Nazi persecution of its Jewish population had begun.

I was curious about the correspondence going to and coming back from the Vatican around these two extremely sensitive issues. Most surprising to me were letters to German bishops, the nuncio, or to the pope himself from German Catholics, including priests, who hoped to find some way to be both true to their bishops and to Hitler. I will give just one example. Princess Georg von Sachsen-Meiningen, who had joined the Nazi party already in May 1931 on her thirty-sixth birthday, tried to explain her distress in a letter to the Holy Father. She was responding to the fact that in the fall of 1930, the pastor of Kirchenhausen bei Heppenheim in the Diocese of Mainz declared in a sermon that no Roman Catholic could be a member of the Nazi Party, and, further, any active member of the Nazi party could be refused the sacraments. Countess Klara-Maria wrote to her pope, “as a good Catholic, I fear to end up in a conflict of conscience and to be in danger of punishment by the Church. If these measures and rules of the Mainz diocese are taken up by other dioceses, I will not be the only one to find myself in this conflict, but joined by hundreds and thousands of men and women who have decided to heroically fight for any culture or world opinion that will destroy Marxism and Bolshevism.”

While letters like this must be weighed against a population of nearly thirty million German Catholics, what they tell us is that fear of losing their flock to the growing Nazi movement was a factor for the Vatican and the German Catholic Church when making decisions. In lifting their ban on Nazi membership for Catholics, a decision was made to compromise, especially if, as Hitler stated in his March 23 address, the Church would be left alone.

This thinking was at play – alongside prejudiced views of Jews buttressed by 2,000 years of Church teachings – when the next test came: the April laws of 1933. Pope Pius XI himself was asked to intervene in a letter from unnamed – I am quoting here – “high-ranking Jewish notables.” In an internal memorandum, the pope transmitted this request to Secretary of State Pacelli. The precise language Pacelli, the future pope, used is as follows: “It is in the tradition of the Holy See to fulfill its universal mission of peace and love for all human beings, regardless of their social status or the religion to which they belong […].” The memorandum then asked for the advice of the papal nuncio in Germany, Cesare Orsenigo, and of the German bishops in formulating a response. The answer sent back from Berlin was clear: the Church should not intervene beyond conveying “the will of Catholicism for universal charity.”

Why this response? Fear of alienating Catholics attracted to Nazism; fear of losing the independence of Church practices in the new Nazi state, and, finally the mentality best captured by the response of Cardinal Michael Faulhaber of Munich. In a letter dated April 10, Cardinal Faulhaber, like Orsenigo, discouraged the Holy See from intervening. He wrote to Pacelli: “Our bishops are also being asked why the Catholic Church, as often before in history, has not come out in defense of Jews. This, at present, is impossible, because the war against the Jews would also become the war against the Catholics; also, the Jews can defend themselves, as the quick end to the boycott has shown.”

Five years later, after the devastating Night of the Broken Glass pogrom, Secretary of State Pacelli would again receive a missive asking the Vatican to denounce what many consider to be the opening act of the Holocaust – total destruction of every Jewish man, woman and child. This time, the missive was from one of his own. Cardinal Arthur Hinsley, 5th archbishop of Westminster, wrote to Pacelli requesting papal condemnation of the pogrom. Pacelli refused on behalf of the pope, who had recently suffered a heart attack. The official Vatican response read as follows: “The Holy Father Pius XI’s thoughts and feelings will be correctly interpreted by declaring that he looks with humane and Christian approval on every effort to show charity and to give effective assistance to all those who are innocent victims in these sad times of distress. [Signed] Cardinal Pacelli, Secretary of State to His Holiness.

We have here another unambiguous example that Pacelli, despite being informed about the horrendous details of the pogrom in Germany, was not encouraging of a public statement by the Holy See condemning Nazi Germany specifically, or the November pogrom specifically, or singling out suffering Jews specifically by name—even when asked to do so by a prince of his own church. He was comfortable only with a statement broad enough to apply to all “innocent victims.”

To wrap up on the topic of the 1922-1939 archives, these millions of documents still have so much potential. Open since 2006, fourteen years have not nearly exhausted the possibilities. For me, I learned the lesson that the response of the Catholic Church to Nazi treatment of Jews cannot be separated from the Church’s response to Nazi treatment of Catholics during the 1920s and 1930s. What do I mean? The last weeks of March and first weeks of April 1933 make painfully clear that the Catholic Church’s decisions and responses to persecution of their own co-religionists influenced and even dictated their tepid response to the mistreatment of Jews. Another lesson: the role that 2,000 years of Catholic prejudice against Jews played from the lowest to highest levels of the Church during these fraught years should and must be studied beyond the person of the pope himself. The 1922-1939 archives are rich with material from ordinary Catholics, their priests, nuns, bishops, cardinals and from their Jewish neighbors, grasping for any help they might find and typically not finding it.

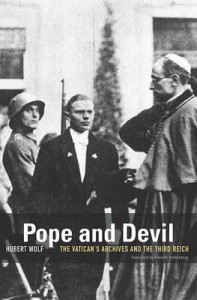

Fast-forward to March 2020. Since their opening on March 2, the fascination with the 1939-1958 materials has only grown. A documentary by award-winning director Steven Pressman, titled Holy Silence, premiered in January of this year. It garnered over 3,000 views when shown as part of a recent joint program between the Holocaust Museum and the Jewish Film Institute of San Francisco. An interview with Hubert Wolf, a historian at the University of Münster whose team was among those in the archives that first week in March went viral. More recently, Brown University historian David Kertzer’s article in The Atlantic on his and his research collaborators’ findings resulted in a counter-article in none other than L’Osservatore Romano. This is the daily newspaper of the Vatican City State which reports on the activities of the Holy See and events taking place in the Church and the world.

Earlier this month, I stood in the Vatican Apostolic Archive for the first time in my life. Where does one begin with the many questions that I have been accumulating since that first day in the Catholic University archives? With limited time to work in the archive, I decided to follow up on an old question that has nagged at me since those early days at the Catholic University Archives – that of Pius XII’s thought process as he pleaded for clemency for Germans indicted and convicted for war crimes by Allied courts in occupied Germany. Scholars have already established that Pius XII and his key advisors involved themselves in clemency efforts for convicted German war criminals, most especially Catholic ones. I recalled that even Muench had questioned this practice, telling U.S. High Commissioner John J. McCloy in 1950 that some championed by the Vatican “were up to their elbows in blood.”

Selecting a folder labeled “Prisoners of War, 1950-1959” from the papers of the Vatican’s diplomatic headquarters in Germany, I started to turn the fragile pages in the beautifully appointed “Pius XI Study Room.” Midway through the folder, the subject heading “Case Oswald Pohl” caught my eye. Oswald Pohl joined the Nazi party in 1926 and the SS in 1929. The SS, or Schutzstaffel, was an elite quasi-military unit of the Nazi party that served as Hitler’s personal guard and as a special security force in Germany and the occupied countries. Pohl became chief of administration at SS headquarters in February 1934, responsible for the armed SS units and the concentration camps. Ultimately, he headed a sprawling organization that was responsible for recruiting millions of concentration camp inmates for forced labor units, and also responsible for selling Jewish possessions—jewelry, gold fillings, hair, and clothing—to provide funds to Nazi Germany. On November 3, 1947, in the “U.S. versus Oswald Pohl et al,” the U.S. Army sentenced Pohl to death. During the three-year confinement in Landsberg prison that followed the trial, Pohl converted to Catholicism. This, however, did not prevent his execution by hanging on June 8, 1951.

The dates in the folder sitting in front of me also caught my eye – April 1951, less than 8 weeks before Pohl’s execution date. There are three memos written (in Italian) from Muench, headquartered in Kronberg, Germany, to the Vatican’s Substitute Secretary of State Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Saint Pope Paul VI and at that time, Pius XII’s closest advisor and friend. On April 2, Muench wrote to Montini, “I consider it my duty to remit to Your Excellency […] newspaper articles which report news of the Holy Father sending a Papal Blessing to Mr. Oswald Pohl, former General of the SS., sentenced to death in Landsberg.” Muench’s 2nd memorandum to Montini got even more interesting and confirmed that indeed, Pohl had received a Papal Blessing via telegram. Let me pause to briefly explain that The Apostolic Blessing or Pardon at the Hour of Death is part of the Last Rites in the Catholic tradition. The Christian News Service in Munich issued a clarification that, according to Landsberg prison chaplain Carl Morgenschweis, the telegram conferring the Papal Blessing was “purely private, and not a diplomatic step or a Vatican stance.”

Specifically, a Father “Costatino Pohlmann” sent an urgent request to Pius XII with a request that a Papal Blessing be sent to Pohl on the eve of his death, in keeping with Catholic practice, and the pope did so. In Muench’s view, this was “not at all a matter of a telegram from the Vatican, much less a position taken by the Pope on the Pohl case.”

In the third and final memo from Muench to Montini on the matter, Muench took the time to send to Montini – second only to the pope in terms of power and position – a copy of an essay Pohl had written while imprisoned. The essay was titled “My Way to God.” Muench ensured Montini that the essay had come from the heart. Father Morgenschweis “closely followed the radical change of Pohl,” and wrote the preface, confirming that in Father Morgenschweis’ eyes, Pohl converted “only for the beneficial influence of God’s grace” and marked “the sincere return to the Lord of a misguided soul.”

What are we to make of Pius XII granting the Apostolic Blessing or Pardon at the Hour of Death to Oswald Pohl, a recently converted Catholic condemned to death as one of the greatest Nazi overlords of the slave labor system? A week in the new archives cannot answer such a question of moral, ethical and theological significance. It did provide, at least for me, a sense that more historical evidence exists in other parts of this or another of the newly opened archives. I believe the core story we tell now about the Vatican, the Catholic Church, and the Holocaust will be fundamentally altered after historians have done their work. But it will take time.

To conclude, why all the intense interest in these archives, 75 years after the end of World War II? And what might they mean for Christian-Jewish relations, which have been on a steady and positive path since the Church’s rejection of antisemitism as a sin with the Nostra Aetate declaration of 1965? There is no doubt that some documents will bring to the fore very tough conversations. Other documents will bring cause for celebration. The vast majority will engender elements of both. It is an overdue conversation, and one that must be approached with humility before our Jewish brothers and sisters – for our Church (my Church) has much to answer for that the Nostra Aetate declaration does not erase. When announcing the opening of these archives, His Holiness Pope Francis said, “the Church is not afraid of history; rather, she loves it … I open and entrust to researchers this documentary heritage.” This is our moment to study the past in a clear, responsible, precise way. This is our moment to accept we will find stories across the full spectrum of the human condition, from the most depraved to great acts of kindness. This is our moment to be equally honest about both the failings and triumphs we are already finding, from top to bottom. Thank you.