Association of Contemporary Church Historians

(Arbeitsgemeinschaft kirchlicher Zeitgeschichtler)

John S. Conway, Editor. University of British Columbia

Return to index.

July/August 2008— Vol. XIV, no. 7-8

Dear Friends,

I very much hope that all of you in the northern hemisphere are now enjoying this holiday season, but that you will still find time to read this issue of our Newsletter. In the interests of denominational and ecumenical equality, I include in this issue two reviews about the German churches, one about Catholics and one about Protestants, as well as two about different kinds of British Protestantism. I hope that these prove to be of interest. I am always glad to have your reactions, but PLEASE remember NOT to press the reply button above unless you want your remarks to be shared by all of our 500 members.

Contents:

1) Conference Announcement: Regent College History Conference, Vancouver: July 25-26, 2008 – beginning at 1 p.m. – registration at door

“Exploring new frontiers in Evangelical History” Speakers: George Marsden, Mark Noll, David Jones, David Hempton, Bruce Hindmarsh

All welcome

2) Book reviews:

a) ed Damberg and Liedhegener, Katholiken in den USA und Deutschland

b) Ringshausen, Widerstand und christlicher Glaube

c) Shuff, Searching for the true church

d) Hughes, Conscience and Conflict. Methodism, peace and war in the twentieth century

2a) Wilhelm Damberg and Antonius Liedhegener, eds. Katholiken in den USA und Deutschland. Kirche, Gesellschaft und Politik. Münster: Aschendorff. 2006. Pp. vii, 393. Euros 24.80. This review appeared first in the Catholic Historical Review, and is here reprinted by kind permission of the author.

At the time of the Second Vatican Council Germany exercised a powerful attraction for Americans seeking doctorates in Catholic theology. German theologians like Karl Rahner, Hans Küng, Walter Kasper, Joseph Ratzinger, and Johann Baptist Metz all counted Americans among their students. Today the tide runs in the other direction. Astonished at full churches in the United States, and impressed with the vitality of American parish life, German Catholics now come in increasing numbers to the United States to investigate a level of religious practice inconceivable in Germany today.

One of those impressed by American church life is the German businessman, Dr. Karl Albrechts, whose Aldi supermarkets can be found on both sides of the Atlantic. His generous grant provided funding for a conference in Berlin in May 2004, at which reports on church life in Germany and the United States were given by eighteen experts from both countries. Delivered in English, the papers have now been translated into German and are published in this volume. Several of the presenters report on the situation in the other country a happy example of two-way cooperation and enrichment.

Despite their great differences, Catholics in both Germany and the United States share elements of a similar history. In both countries Catholics are a minority, suspected by the majority from the mid-nineteenth century to the eve of the Second Vatican Council of owing primary allegiance to the Roman pontiff. German Catholics responded to this challenge by forming a flourishing milieu consisting of numerous Catholic organizations including a political party. American Catholics lived largely in a self-imposed ghetto, dismantled by Vatican II’s opening to the world, and by the entry of increasing numbers of American Catholics into their country’s social, cultural, and educational mainstram.

In other respects church life in the two countries is dissimilar. American parishes and other church institutions have always been voluntary associations, founded and supported by their members. This imposes heavier financial burdens than those borne by Catholics in Germany, whose parishes, church buildings, and other institutions are provided “from above,” and supported generously from public funds. The need for self-support gives American Catholics a greater sense of ownership than those in Germany.

Paradoxically, however, the Catholic Church in Germany has been, since Vatican II, more democratic than that in the United States. Germany’s National Synod from 1972 to 1975, with both lay and clerical representation and enjoying legislative and not merely advisory power, is inconceivable in this country. Parish Councils and diocesan Pastoral Councils are found throughout Germany. In the United States their existence depends on the local pastor or bishop. Also dissimilar is the educational system in the two countries. Schooling, from kindergarten to university, is a state monopoly in Germany. Home-schooling, a small but flourishing feature on the American educational scene, is forbidden by law in Germany under penalty of heavy fines or imprisonment. The German state accommodates Catholic interests through church-supervised religious instruction for Catholic students in state schools, and by public support for state regulated Catholic schools, including the faculties of Catholic theology at the state-supported universities. Of special interest for German readers is the flourishing system of adult catechesis in the United States (the Rite of Christian Initiation for Adults), still in its infancy in Germany.

The book will be of greater interest for German readers than for Americans. The view of American Catholicism which it presents is colored by the selection of American presenters. They include such well known authorities as Andrew Greeley, Margaret and Peter Steinfels, and Leo O’Donovan SJ. Unfortunately missing are others no less distinguished who could have presented a more balanced picture: Richard John Neuhaus, Michael Novak, and George Weigel.

John Jay Hughes, St Louis.

2b) Gerhard Ringshausen, Widerstand und christlicher Glaube angesichts des Nationalsozialismus, Berlin: LIT Verlag 2007. 509 pp ISBN -104/22/08 3-8258-8306-X

The reputations of those Germans who joined the anti-Nazi resistance movement, or who participated in the abortive plot to assassinate Hitler on July 20th 1944, have fluctuated wildly over the past sixty-five years. At the time, they were regarded by the Nazis, and by many of the established elites, as traitors. Their immediate arrest, summary trial and brutal execution were accepted as being duly deserved for such a heinous crime. But after 1949, the new government of the Federal Republic, based in Bonn, made strenuous efforts to revise this verdict. Instead these men were portrayed as heroes who had sacrificed their lives for the honour of the nation, and as such absolved others of the guilt of having served Nazism without protest. Indeed large-scale and deliberately organized campaigns were launched to show these men as being in continuity with a “better Germany”, which looked back to an aristocratic past worthy of current emulation. This was all part of an attempt to find a usable history on which to base the new West German democratic experiment. These resistance figures could be held to embody positive attributes and traditions, especially if they were aristocrats by birth or practising Christians by conviction.

Such propagandistic attempts often lent themselves to hagiographic overtones. So it was hardly surprising that in more recent years the sceptical work of a younger generation of historians has had a corrosive effect on such glossy portrayals. It is now widely known that many of the July 1944 conspirators had earlier held pro-Nazi sympathies, or had even belonged to the Party. Others, particularly many of the more conservative members, had loyally served in the Nazified German army, and even, at least to begin with, had failed to realize the nihilistic ambitions of their Leader.

So the arguments still continue about the motives of these men; (they were almost all men); also about the political goals they planned to implement in any post-war settlement; but above all about their religious beliefs, as one strong source of their fateful opposition. This is the particular emphasis in Gerhard Ringshausen’s ten biographical case studies of Protestant actors in these traumatic events. He is careful to eschew any attempt to see their careers though the prism of post-war political or religious “correctness”, and instead concentrates on the contemporary evidence available through letters and papers preserved principally by family members. The picture he presents is therefore rich in detail and sympathetic to the crucial dilemmas they all faced.

Religion undoubtedly played a large part in both the indictments and also in the defence statements of these men at their trials after the July plot had failed. To the Nazis, these convictions, if sincere, were proof of the conspirators’ disloyalty to the regime. The defendants’ pleas that their religious obligations had a superior claim was rejected outright, or as a mere pretence to be dismissed out of hand. But others, including historians, have found the validity of such claims to be problematic. The Protestant Church had great difficulty in justifying political murder, especially of the head of state. However evil the Nazi regime and its totalitarian pseudo-religion may have been, the church authorities and their theologians still found it a difficult assignment to abandon centuries of state-affirming Lutheran theology. Attempts to justify the conspirators’ action on Christian grounds – and thereby to separate them from any taint of being influenced by communism – were ardently made, but sceptically received, in the immediate post-war years. Later when historians began to depict a more differentiated pattern of resistance activities, they also perceived a wider range of ethical or religious motivations. With the passage of time, the earlier self-justifications of the resistance participants, or even the cult of “martyrs”, has been replaced by a more sober assessment of the complexity of their situation. Ringshausen places his individual case histories within this broader perspective.

For this reason he avoids the often-used but misleading categorizations which depict the members of the resistance movement as “national conservatives” or “Prussian Protestants”. Instead he draws out the variety of influences which brought these men together to pursue the common goal of ridding Germany of the Nazi tyranny. As the only theologian in the group, Dietrich Bonhoeffer had probably the most coherent religious motivation, connected with his abiding emphasis on ethics. But Ewald von Kleist, a leading landowner and layman, was equally fervent in opposing Nazism from a traditional Lutheran perspective. Moltke, the great-nephew of the famous general, and owner of the Kreisau estate in Silesia, had an American mother who espoused Christian Science beliefs. Elisabeth von Thadden was strongly influenced by the ideas of Christian pacifism, until she was denounced to the Gestapo and executed in September 1944. To the Nazis, of course, the particular variety of Christian motivation was of no account. Their determination to liquidate all opposition was only exacerbated by their virulent bias against the members of the aristocracy or resolute churchmen.

Ringshausen’s contribution is to draw out the variety of often conflicting attitudes and influences of the resisters and to present a detailed account of their political and religious stances. But he also makes clear the cost of the processes by which these men had to overcome many religious scruples, and eventually to assent to being agents of political revolution and assassination. In many cases, these men’s crises of conscience were not resolved before they met their deaths. The failure of their attempts to assassinate Hitler was followed by a widespread rejection among their fellow churchmen. So Ringshausen’s depiction of the convoluted relationship between faith and political resistance will be helpful for future discussions of these complex issues.

JSC

2c) Roger N.Shuff, Searching for the true church. Brethren and Evangelicals in mid-twentieth century England. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Strick Publishers/Paternoster 2006 Pp 296. ISBN 1-59752-794-7.

The Brethren community is a branch of English evangelical Protestantism, which was founded under the influence of an early nineteenth-century preacher, John Nelson Darby. He gained a substantial following in Devonshire – hence the commonly attributed name, Plymouth Brethren. In the wake of the Napoleonic wars, Darby was strongly convinced of the imminence of the Second Coming of Christ, and hence called on his followers to separate themselves from the evil world, and to prepare themselves by prayer and witness for the final rapture. This world-renouncing piety was also repelled by the corruption of the existing churches, and hence rejected any professional ordained ministry in their assemblies. Instead they placed, and still place, great emphasis on the weekly service of communion among their believers. Despite the disappointment of their eschatological hopes, the Brethren established themselves across Britain, the United States, in Australia and New Zealand, and even founded assemblies in Europe. Their history in the twentieth century has now been succinctly, but not uncritically, described by two parallel books, both published by Paternoster. As well as the above, there is now the account by Tim Grass, Gathering in His Name. The story of Open Brethren in Britain and Ireland(2006) Roger Shuff, who writes as a detached insider, has as his main concern to trace the influence of Brethren ideas on the wider English Evangelical movement, especially in the middle of the twentieth century. He contends that the revival of evangelicalism, particularly after the end of the second world war, owed much to the vital association of many key Brethren individuals. But he also argues that this resurgence of evangelical fortunes led to increased tensions within the Brethren community, and has in fact led to a serious decline in its support in Britain.

Because Brethren refused to accept any theologically-trained or professional leadership, they relied instead on the spirit-filled gifts of laymen or senior elders in their assemblies. But this often led to schismatic tendencies. Early on, there was a major split between those who sought exclusively to isolate themselves from the world and other religious bodies, or even to deny fellowship to non-Brethren in their own families. In the 1960s these tensions caused by this seemingly intolerant behaviour led to a parliamentary enquiry, though fortunately a proposed Bill to penalize this sect was turned down on grounds of the wider desirability of religious freedom. On the other hand, there were also those “independents” who were eager to participate in wider evangelical and missionary activities.

In the dark days before and during the second world war, the former group gained adherents from those who sought religious security in a reassuring spiritual environment. On the other hand, the more open-minded members promoted a pan-denominational expression of evangelicalism, which was to play a considerable role in the success of the post-war evangelical “crusades” of a young American preacher Billy Graham.

Brethren, and many Evangelicals, were naturally sceptical about the kind of ecumenical endeavours undertaken at this period by the main-line churches, such as those connected to the World Council of Churches. Instead they sought to strengthen such clearly evangelical associations as the Inter-Varsity Fellowship, or, with some reservations, the Keswick Convention. They gave strong support to academically credible scholarship in biblical studies, as undertaken in such colleges as Tyndale House, Cambridge, the London Bible College, or Regent College, Vancouver.

But, as Shuff shows, these endeavours only widened the gulf between the external-looking and the introspective or “isolationist” elements of Brethrenism. Their respective views of the true church proved critically divisive, and have remained so. For the more open-minded Brethren, the revival of evangelical fortunes also proved problematic. They had long assumed that all other religious life beyond their own assemblies could only decline until the parousia. But the evangelical resurgence cast doubts on this assertion. Coupled with this was the serious threat of the 1960s counter-culture, especially among youth with its rampant optimism and hedonism. In the evangelical community, this found expression in the charismatic movement with its vibrant ecstatic exhortation to spiritual encounters. To many conservative Brethren , these phenomena, such as speaking in tongues, and the clearly antinomian atmosphere, were too much of a challenge. Yet they lacked an attractive alternative which could offset these enthusiasms. The result has been an undoubted decline in numbers, as many younger members have been drawn away to more accommodating evangelical gatherings.

Shuff also describes the sad story of how the hard-liners fell under the sway of an American preacher who finally misused his powers and was publicly disgraced. The result was a sharp accentuation in the contrast between the different sections of the Brethren community. The isolationist group is greatly reduced, while the more progressive “independents” still struggle to find an appropriate relationship to other branches of the evangelical fraternity. Having tacitly abandoned their eschatological expectations, the issue of the group’s relationship to the wider world and its future course still remains to be tackled.

JSC

2d) Michael Hughes, Conscience and Conflict. Methodism, Peace and War in the twentieth century. Peterborough, U.K.: Epworth Press 2008, 336 pp.

Michael Hughes, a professor of modern history at the University of Liverpool, has given us a lucid account of the attitudes of British Methodists towards the issues of war and peace during the dramatic and conflict-ridden twentieth century. Why Methodists? Because they formed a cohesive group in British public life whose members, both clergy and laity, gave a remarkably consistent lead on these issues, both orally and in writing. Their sermons and speeches, and the columns of the Methodist newspapers, provided Hughes with an abundance of raw material and a clear picture of the significant issues which recurred again and again across these years. He also seeks to repair an omission in most secular histories of this period, which entirely ignore the religious dimension of public opinion, or dismiss the views of churchmen as irrelevant.

By tradition, Methodists are not obligated to give support to secular governments. Their political stances were, and are, instead drawn from the impulses of conscience and a reading of the Bible, especially the Sermon on the Mount. Methodist politics were therefore based on the morality of the pursuit of peace, and an abhorrence of war and its destructive capacities. Their continuing difficulty was, and still is, how to fit such lofty ideals into the contingencies of world politics. A shared moral passion does not lead easily into agreement when faced with the complexities of practical policy, especially in international affairs. This fact was largely responsible for the lack of effective influence by such religious groups as the Methodists as the champions of the “Nonconformist Conscience”.

Already before the first world war this high-minded tradition of pursuing peace and non-intervention in the affairs of others was becoming increasingly outmoded in a world of imperial rivalry and European alliances. The need to deal with situations in which the use of force alone could offer the prospect of preserving peace, or preventing gross injustices, was to become a source of heartfelt contention in the Methodist ranks. A minority, out of conscience, maintained that the Gospel of Jesus Christ could not be compatible with the practice of war, and called on its supporters to adopt an unequivocal refusal to bear arms. But, on the other side, the majority had been persuaded that loyalty to their beliefs was not compromised by a readiness to defend their nation against any aggressors. Many were also supporters of Britain’s far-flung military and naval commitments. Or they were convinced of the civilizing mission of the British Empire, where so much of their missionary endeavour was engaged. Most Methodists, when confronted with Germany’s aggressive tactics, agreed, reluctantly, with the British naval response, but were highly uncomfortable with Britain’s alliance with the despotic regime of Czarist Russia. Nevertheless, the German aggression against Belgium in August 1914 was clearly a moral issue and relieved many consciences.

A significant minority of Methodists dissented from the popular display of jingoism and excitement which enthusiastically hailed the outbreak of war. For the followers of the Prince of Peace, war could solve nothing. This led many to advocate and even practise conscientious objection. But the intolerant treatment of such men when summoned to appear before recruitment tribunals only increased tension. At least a hundred Methodists were imprisoned and subjected to harsh, even brutal treatment, including three who were later ordained.

In the aftermath of the war, Methodist consciences were smitten with remorse. Understandably they eagerly supported political platforms offering a different ordering of international affairs, such as the League of Nations. As a result they became susceptible to the allurements of an idealistic optimism, and used their limited political influences in such causes as international reconciliation, disarmament or even the attempt to secure the abolition of war.

The drawback of such a stance, Hughes rightly points out, led to their agreeing that the 1919 Peace of Versailles was based on vengeance rather than on justice. But what they did not realize, and what Hughes does not explain, was that this moral approach played into the hands of the German conservatives united in their belief in the Versailles Treaty’s iniquity. Methodists blamed the Allied governments, but failed to note that Germany had never expressed any regrets about its aggressions in Belgium or elsewhere. They never asked what sort of peace settlement the Germans would have accepted as being non-vindictive. The answer is none, since most Germans continued to believe that they deserved to win the war, and had only been sabotaged by enemies at home, such as the Jews.

Much of the Methodist controversy of the 1920s and 1930s was essentially wrong-headed, being born of a refusal to believe in the essential evil of international conditions. Even if only a minority of the church’s members were involved, the heat of the debate, especially in the Methodist Peace Fellowship, gave it a feverish pitch. But the failure of the idealists’ efforts over international disarmament in the 1930s, when Britain’s delegation to the Disarmament Conference was led by a prominent Methodist as Foreign Secretary, was to become a bitterly disillusioning process. Religious groups such as the Fellowship of Reconciliation or the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches redoubled their efforts to promote the cause of peace. But apart from passing vague and moralistic resolutions, which stressed Christian brotherhood, they could achieve little. In many cases this minimal and ineffective approach seemed to be enough to relieve their consciences.

Hughes might well have made more of the recurrent impotence of church opinion, most notably in the inter-war period, but also in the great debate over nuclear weapons in the 1960s. One reason was undoubtedly the fact that the fervour of religious pacifism was not matched by any realistic appreciation of the underlying political and international factors. Pacifists like to wrap themselves in the unassailable garments of morality, but had to be reminded that they did not have a monopoly of hatred of war or enthusiasm for peace. It was not enough to accuse politicians who advocated rearmament of being warmongers, or to assume that disarmament, especially of nuclear weapons, would issue in an unprecedented era of (Christian) peace. As Hughes, notes, a strong dose of Christian realism, such as delivered by Reinhold Niebuhr in the United States, never reached the Methodists – at least not in the 1930s, or for many others, not even later.

In 1939, the awful character of the Nazi regime with its ideology of aggression and racial supremacy, helped to simplify ethical dilemmas. On the other hand, as the second world war progressed, the realization grew that the new military technologies raised even more radical ethical dilemmas. The question was not whether to fight the war, but how to conduct it within some moral framework. The final apotheosis of dropping of atomic bombs on Japan, and murdering thousands of bystanders and civilians, could hardly be consistent with any traditional doctrine of “just wars”.

The outbreak of war in 1939 crystallized still further the tensions between pacifists and non-pacifist members of the Methodist Church. The former had played too large a role since 1919 to abandon their cause. But by the dark days of 1940 only the extreme wing which favoured submission as the most Christian way still adhered to any belief in the possibility of reconciliation with Nazi Germany, now poised to invade Britain’s shores.

In practice, Methodists bore their full share of the miseries inflicted by German bombing of British cities and towns. They met the challenge of meeting the pastoral needs of so many conscripts on the battle front or behind the lines. Such an emphasis on practical service did not however deter debate about the wider issues of war and peace. The church leaders upheld their newly-adopted commitment to defend the rights of conscientious objectors, though others were fearful lest Methodism become a refuge for “pacifists, peace cranks or c.o.s.” Once more the majority gave support to the national war effort, but were heavily criticized for calling it a “sacred cause”. The Methodist Peace Fellowship still retained several thousand members, though these were now obliged to face unequivocally, because of the incessant war-time propaganda, the horrors they would potentially have to accept if their pacifist position had been adopted.

Hughes noted that there was less debate in Methodism than in Anglicanism about the relationship between means and ends in modern warfare. Most accepted the government’s argument that bombing German cities was necessary to hasten the end of hostilities. The same applied to Japan. From the relative safety of Britain, few were able to imagine the extent of the sufferings inflicted on distant peoples, let alone on whole races such as the Jews. Only afterwards did the realization sink in that such actions required the rethinking of ideas of Christian pacifism.

In the post-war world the threat of apocalyptic destruction through atomic weapons induced a more sober climate. There were still some like the sometime President of Conference, Donald Soper, who combined moral fervour with political naiveté, especially with regard to the Soviet Union. But the majority, though not pacifist, became charged with the responsibility of formulating ethically tenable positions on nuclear weapons. Many Methodists supported the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament because they saw that the use of such weapons was highly disproportionate to the ends desired. But this insight was not confined to Methodists alone.

These debates led on to wider issues in which Methodists joined, particularly in the pursuit of global justice. Hughes’ able survey shows how concerned this group of Britons was about the background issues of world peace, and how the Methodist tradition of social activism led to a more critical view of the economic and political structures on the international level. Moral obligations did not end at the nation’s frontier.

Until the end of the century, a strong segment of Methodism continued to hold that the morality of the Sermon on the Mount ought to be reflected in the nation’s policies, and justified civil disobedience if they were not. But a larger majority had learnt that the complexity of international relations could not be so easily resolved. So too, the increasing emphasis in Methodist discussion on global poverty obliged a deeper examination of the basic causes of global injustice. Such issues came to occupy Methodist attention, overshadowing even the spectacular and welcome collapse of the Communist empire.

In the 1990s, the wars in Iraq and the Balkans aroused predictable reactions from church circles. Was foreign intervention morally justified in the interests of a wider international security? After September 2001, the American retaliations against both Iraq and Afghanistan, and the British Labour government’s subsequent support, caused enormous controversy. The resulting civil wars have only added to the difficulty of finding any secure moral compass. Indeed Hughes comes to the conclusion that the nature of modern conflict now seems irreconcilable with traditional Christian teachings about just wars.

Despite the clear decline in Methodism’s numbers in Britain, its adherents still maintain much of their traditional ethos on issues of war and peace. Many are still influenced by an optimistic belief that an individual commitment to oppose war will transform the world. Even though Christian pacifism has remained marginal, and has never affected government policy, nevertheless the basic moral concerns of most Christians has been a significant factor in public debate throughout the century. At its best such witness pointed to the standards of international behaviour to which all Christians aspired. At its worst it fell back on moral platitudes.

Hughes naturally disagrees with those who, in recent years, have seen all religions as malign forces undermining rational solutions to international problems. His thoughtful account of the Methodist experience in the past hundred years, shows, to the contrary, how their consistent commitment and witness have sought to promote peace, despite all the obstacles involved. Their debates on how such ends should be achieved echoed much of the wider society’s concerns. But theirs was a voice which needed to be heard, and was in fact often heard. We can be grateful to Professor Hughes for this valuable and dispassionate analysis.

JSC

With every best wish to you all

John Conway

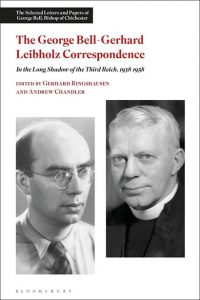

The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration.

The volume opens with Bell’s September 1938 letter to Bonhoeffer assuring him of his willingness to help the Leibholzes. George Bell had been actively involved since 1933 in assisting refugees from Nazi Germany, including members of the Confessing Church who were affected by the Nazi laws. The early correspondence offers a detailed picture of the difficulties refugees faced even after they reached a safe country. They could not assume, of course, that they would remain in safety; Leibholz’s brother Hans and his wife managed to reach Holland, but committed suicide in 1940 after the German invasion. Added to this anxiety were financial concerns (Germany froze Leibholz’s assets when he fled, so they arrived in England with nothing), worries about the family they had left behind, existential concerns about employment and the future, and dealing with anti-German prejudice in England once the war began. In May 1940 Leibholz was interned as an “enemy alien” on the Isle of Man, along with a number of Confessing Church pastors and their wives. Bell managed to obtain his release in August 1940, after which the two men pursued the possibility that the Leibholzes might immigrate to the United States. With the assistance of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contacts in New York, Leibholz was offered and accepted an invitation to Union Theological Seminary in 1941, but by then the door had closed due to new U.S. restrictions on immigration.