Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 26, Number 3 (September 2020)

Fierce Culture Wars Over Three Construction Projects in the German Capital Region

By Manfred Gailus, Technical University of Berlin; translated by Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

Dr. Manfred Gailus is an expert on the history of the Berlin churches during the Nazi era and regularly writes about the ongoing impact of that history on the current religious, ecclesiastical, and political scene in the German capital, where he lives and works.

Three historically significant architectural projects in the Berlin-Brandenburg capital region have been the subject of heated public disputes for years. Unmistakenly restorative and in part explicitly religious-political, they exemplify a problematic cultural policy. In their origins, all three projects exhibit common or similar structural features, indicating that this concerns more than simple and singular architectural reconstruction projects. All three construction projects were initially announced as private or small-group campaigns financed by donations, but were unable to raise the necessary financial resources for realization. The protagonists then proceeded to appeal to public bodies (the Federal Republic of Germany, the Berlin Senate as state government, the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD), the Evangelical Church Berlin-Brandenburg-Silesian Upper Lusatia (EKBO)), effectively forcing these state and church bodies to help bring these lofty project ideas to fruition by massive financial grants. In all three cases, in fact, the project implementation only got off the ground through subsidies from public and church funds (tax money, church tax money). In all three projects, the same or similar interwoven networks of denominational and political figures played and still play an essential role. In addition, partly anonymous donors (private donors, associations, etc.) can buy their way into the design of the emerging buildings through large donations and thus write their private wishes, preferences, and motives into the public space. Anyone who has money can “immortalize” themselves here. Those who don’t are unlucky.

1) Reconstruction of the Berlin Palace

Idea: Once again, the German capital should have a striking architectural symbol in the city center. And in the twenty-first century the new symbol will now become the old one—the historic Hohenzollern Palace. Of course, today it will be filled with different spiritual contents than the lost Prussian monarchic divine grace. The building is now in the city center: on the outside, predominantly heroic Baroque Prussia; on the inside, world culture is to be presented under the Humboldt Forum label. The state provided the financing and contributed around 500 million euros. About 100 million was financed through donations and private “purchases” for the building. The organization of the project is run by a foundation and a development circle that is primarily responsible for fundraising. In these circles, much of old Prussia has been revived—nostalgic feelings: We are getting our old castle back! The main actors in these networks include: Monika Grütters, an avowed Catholic of the ruling CDU party, in her capacity as Minister of State for Culture; Agricultural machinery dealer and first project initiator Wilhelm von Boddien, as managing director of the supporters’ association; the Protestant theologian Richard Schröder from Humboldt University; and recently, also the General Director of the Humboldt Forum, Hartmut Dorgerloh.

There were quite a few public controversies in the course of the reconstruction process. The most glaring unreasonable demand recently was: a gold-plated cross on the dome above the main entrance and a slogan mounted on the dome taken from two biblical passages (Acts 4:12 and Philippians 2:10): There is no other salvation, and no other name given to men, except the name of Jesus, to the glory of God the Father. That at the name of Jesus all should bow down on their knees who are in heaven and on earth and under the earth. In the spirit of throne and altar, Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV had this slogan installed in 1848, the year of the revolution, instrumentalizing these words for political purposes. This was already a provocation for the Liberals and Democrats of 1848. In the end, the king crushed the democratic revolution of 1848-49 with Prussian soldiers. The golden “Reichsapfel” (orb) at the foot of the gold cross now features a donor dedication from “Otto-Versand Hamburg”. It reads: “In memory of my husband Werner A. Otto 1909-2011. Inga Maren Otto.” The widow of the founder of the mail-order company and current patron financed the gold cross with a private donation of one million euros.

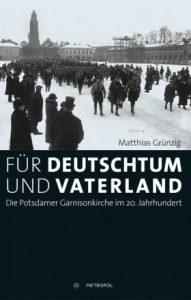

2) Garrison Church, Potsdam

The idea: Resurrection of the former Prussian military church (destroyed by the British Royal Air Force in April 1945) as the dominant urban structure of the Brandenburg state capital Potsdam. The principle actors here presumably thought: A church lighthouse is to be built here for missionary work in the East, which became “godless” in the time of the GDR. The entire project would cost well over 100 million euros. The amount raised for the reconstruction project remained modest—not enough to rebuild anything. In the meantime, people have to content themselves with only rebuilding the church tower, which is now under construction. This alone will cost well over 40 million euros. The project organizers were unable to raise even this sum from donations alone. The church tower is now mainly financed from grants from the Federal Republic and grants (loans) from the EKBO and EKD. The organization of the project is in the hands of a “Garrison Church Foundation” and a circle of friends who, like the palace, run the fundraising campaign. Relevant networks are: a church group around former bishop Wolfgang Huber, parts of the regional church (EKBO), and supporters from the EKD. It is currently unclear whether the project can be fully implemented. The ongoing conflicts over the building have divided the citizens of Potsdam. The current situation seems to be a mess. The US star architect Daniel Libeskind recently volunteered and announced that he will be offering proposals to resolve the architectural dispute.

For the general public, the most unreasonable demands are: a Prussian throne-and-altar nostalgia stimulated by the project, and the tendency of the builders to engage in historical falsification and historical revisionism. The steeple with the Prussian eagle, which has already been restored according to the historical model, is currently located next to the tower in a protective metal cage. The hungry Prussian eagle would like to learn to fly again, should it find its way to the top of the tower anytime soon.

Note: The opposition movement, to which the Martin Niemöller Foundation belongs, has recently installed a website “Lernort-Garnisonkirche.de” on the Internet, which provides comprehensive information on the historical context of this controversial Prussian-German site of remembrance.

3) “House of One,” Central Berlin

The idea: In the center of Berlin, on the site of the former St. Peter’s Church, which was destroyed in the war, a “house of three religions” is to be built to support fellowship among the three Abrahamic world religions. The aim is an inter-religious dialogue in the spirit of Lessing’s ring parable (“Nathan the Wise”). Last but not least, it should be an ecclesiastical “reparation” for the undoubtedly grave “sins” of the Protestant Church during the Nazi era. The initiator is Pastor Gregor Hohberg from St. Mary’s Church (St. Marienkirche) in Berlin, who comes from a GDR parsonage and has been running this project with some success for almost twenty years. Here, too, international donations were to have made the project of 40-50 million euros possible. The donations were sparse. Here again, public donors stepped in: the Federal Republic and the Berlin state government each gave 10 million, in addition to various grants from the EKBO, and from the beginning the project was supported by the strong commitment of church staff. The relevant networks come from within the church: St. Mary’s in the center of Berlin, several church staff members, and various prominent supporters from the cultural scene. The current protagonists include EKBO Bishop Christian Stäblein and the pastor and project “inventor” Hohberg; Rabbi Andreas Nachama (formerly director of the Berlin Topography of Terror Foundation) has also been involved for several years.

Here, too, there are provocative aspects that have aroused criticism for years, particularly regarding the international financial contributions to the project coming from the Qatar Foundation International as well as from controversial groups like the Gülen movement. Indeed, one leading German sponsor withdrew support for the House of One on account of its connection with Gülen. Another striking aspect of the activity of the builders is the denial of the prehistory, because here they are building on the foundations of the former St. Peter’s Church in central Berlin. Berlin’s top Nazi pastor and provost Walter Hoff worked at this church from 1936 to 1945. According to his own admission in 1943, Hoff was involved in Holocaust campaigns during the war in the East. As a potential war criminal, he was never seriously threatened for prosecution for this, but rather was reinstated into church ministry after a period of suspension. The builders of the “House of One” have persistently refused to come to terms with this history since about 2012-13.

*

The obvious parallels between these three architectural projects must provoke objections. It corresponds to the political spirit of the grand coalition, in which the CDU sets the course and the SPD fails and keeps its mouth shut. Social Democrats have often been connected to these projects through networks of connection—people like the (former) Prime Ministers of Brandenburg, Manfred Stolpe and Matthias Platzeck, in Potsdam; Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier (he has assumed the patronage of the Potsdam project); the Governing Mayor of Berlin, Michael Müller; former Bundestag President Wolfgang Thierse; and university theologian Richard Schröder, among others. The leading newspaper in Berlin (Der Tagesspiegel) is also remarkably cautiously neutral in its reporting. Its motive, presumably: just don’t stir up any “culture wars” (“Kulturkämpfe “) in the German capital, a place so critical of religion. Parts of the regional church (EKBO) see themselves wonderfully on the offensive with these projects. The cross and Prussian eagle soon over Potsdam again, and now the cross over the atheistic capital Berlin again too. In short: there is much cultural and religious-political restoration on the advance, while little sustained or effective outcry from a critical public can be heard. And in the background behind these seemingly harmless architectural projects, all sorts of networks nostalgic for the old Prussia, friends, and political circles of the New Right gather. They see their chance in these architectural projects and are certainly waiting for their hour to come soon.

Grünzig’s central question is about a building. What was the place of Potsdam’s Garrison Church in twentieth-century Germany? His answer is striking and sobering. Over a fifty-year period, the Garrison Church was the site of nationalist, National Socialist, military, and militaristic activity. Members of the congregation from Imperial Germany to the last days of Hitler’s regime loudly supported those causes, and the Protestant clergy, many of them military chaplains or veterans, promoted them from the pulpit. The church building was the site of memorials, rallies, processions, and ceremonies—to commemorate the Battle of Sedan, to mourn ten years since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, to honor the anniversary of the death of Friedrich II, and to bless the banners of the Hitler Youth. It was both a symbol of an aggressive Fatherland and itself a force in creating and empowering that version of Germany.

Grünzig’s central question is about a building. What was the place of Potsdam’s Garrison Church in twentieth-century Germany? His answer is striking and sobering. Over a fifty-year period, the Garrison Church was the site of nationalist, National Socialist, military, and militaristic activity. Members of the congregation from Imperial Germany to the last days of Hitler’s regime loudly supported those causes, and the Protestant clergy, many of them military chaplains or veterans, promoted them from the pulpit. The church building was the site of memorials, rallies, processions, and ceremonies—to commemorate the Battle of Sedan, to mourn ten years since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, to honor the anniversary of the death of Friedrich II, and to bless the banners of the Hitler Youth. It was both a symbol of an aggressive Fatherland and itself a force in creating and empowering that version of Germany.