Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 23, Number 4 (December 2017)

Conference Report: “Protestant Institutions in Central Germany under National Socialist Rule,” Cecilienstift Halberstadt, September 28, 2017.

By Dirk Schuster, Universität Potsdam

This public workshop was jointly organized by the Chair of Modern History of the University of Magdeburg, the Cecilienstift Halberstadt, the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung (state center for political education) Saxony-Anhalt and the Historical Commission for Saxony-Anhalt. In her welcoming speech, Pastor Hannah Becker drew attention to the need to engage in a public discussion to engage in a public discussion on the central topic of this conference. In her bachelor thesis (2016), Elena Kiesel examined the history of the Cecilienstift in Halberstadt during the “Third Reich” and carried out pioneering research in this area.[1] This work initially sparked the idea of researching Protestant institutions during the period of National Socialism. However, ‘institution’ should not be understood as a rigid concept, as was also specifically pointed out by the organizer David Schmiedel at the end. This term rather includes a range of organizational units in its scope.

The second reason mentioned by Hannah Becker in her opening speech for such a workshop is the necessity of keeping the memory concerning the crimes that took place under the National Socialists alive. How very up-to-date this historical awareness should remain was shown in the elections to the national parliament in Germany this year. It was considered a given beforehand that the right-wing party “Alternative for Germany” would join the German Bundestag in the September general elections. Before the election, the staff at the local home for the disabled in Halberstadt were repeatedly asked by a resident whether conditions for the disabled in Germany would now revert back to what they were like under the Nazis.

After the welcoming address by Silke Satiukov, a research overview of the processing of Protestantism for the time of the Third Reich was given by Manfred Gailus. He argued in his remarks that it would only be possible to eventually provide an overview of heterogeneous Protestantism at that time after profound regional studies had taken place. Exemplary of such a successful regional study referred to by Gailus is the double volume on the Protestant Church in the Palatinate (Pfalz) published in 2016.[2]

In the presentations that followed, the diaconal institutions formed the main focus of the workshop. Helmut Bräutigam exemplified the Paul-Gerhard-Stift and its deaconess house in Wittenberg. He pointed out in his speech that the board of directors of the hospital and monastery was initially strongly oriented towards the German Christians, but this attitude changed as early as 1934 towards a more neutral course of thought. Even though the hospital suffered enormously from the lack of skilled staff, the leadership refused to hire Protestants of Jewish origin in the mid-1930s. Likewise, the hospital’s willing involvement in around 300 forced sterilizations of men shows that the monastery and deaconess house became compliant helpers of Nazi ideology. In the subsequent discussion, the question of internal debates or even refusals among employees regarding forced sterilization came up. Bräutigam had not found any indication for these and therefore believes that doctors and deaconesses actively participated but did not speak about it.

In her presentation, Elena Kiesel summarized the results of her bachelor thesis. The Cecilienstift in Halberstadt actually welcomed the takeover of power by the National Socialists. After the “godless” years of the Weimar Republic, the monastery hoped to be able to bring more children into the church. In the following years, however, the first areas of conflict began to emerge. The National Socialist People’s Welfare (NSV) continuously increased their influence on the children’s education of the monastery. Moreover, they obtained complete control over the child care of the Cecilienstift, as it was eventually transferred entirely to the NSV. Even though those responsible protested against the closing of the educator training of the monastery, Kiesel does not see this as “resistance” in the classical sense. Incidentally, letters written in 1943 by pastor Hanse (one of the key protagonists of the monastery) have been found, in which he signed off with the reference “God bless the leader.” This example reveals the broad gap between resistance and consent, as was made clear in the discussion. It did not come to a general rejection of National Socialism, but some did oppose specific abuses on the grounds which could often be found in the attitude, “If only our Führer knew about this.”

Fruzsina Müller came up with similar results. She dealt with the deaconess house in Leipzig. Partly out of conviction, partly for reasons of economic motivation, the house in Leipzig adapted to the new balance of power. The whole ambivalence is shown in the fact that one could hide a “Jewish Christian” deaconess from the Nazis until the end of war, while, at the same time, doctors of the hospital participated in systematic crimes such as sterilization and so on. Blanket statements about attitudes of deaconess houses are impossible. Ultimately, what took place were the (non-)actions of individuals and not the attitudes of institutions and their religious worldview.

Such a conclusion can also be drawn in accordance with the research presented by Hagen Markwardt. The example of the Saxon state institution Großhennersdorf, a state-owned institution since its founding, shows that it was individual motives that led to the transfer of the institute to the Inner Mission (Innere Mission) at the end of 1933. The Inner Mission and the National Socialists pursued parallel interests, according to contemporary thought of the time: While National Socialism was to take care of “high-performance people,” the Inner Mission should look out for the physical and mental “cripples,” as it was said at that time. In 1933, the institute director of Großhennersdorf since 1911, Ewald Melzer, who had a very close connection to the Inner Mission, was in charge of the transfer of the institution to the Inner Mission. From its perspective, the Nazi state was able to pursue its “duty” while at the same time the Inner Mission benefited, also financially, from the new task of administering the institution. As Markwardt noted, National Socialism and the Church did not contradict each other, but rather created a consensus that ultimately benefited both sides.

Rather than analyzing the attitude of individual diaconal institutions during the period of the Third Reich, Norbert Friedrich decided to examine the Kaiserwerther Verband. This was the umbrella organization of the individual deaconess mother-houses. Like a large fraction of German Protestantism, the association initially hoped that National Socialism would support a rechristianisation of German society. The association conformed early on and could thus ensure a continuity of personnel. In the church struggle, the association tried, on the other hand, to keep to a neutral course, thereby leaving it up to individual houses of how they wanted to position themselves concerning the German Christians and the Confessing Church. During the resulting discussion, the question was raised as to how the Kaiserwerther Verband behaved towards euthanasia. In the attitude of the association to euthanasia, Friedrich sees a reflection of the whole attitude of the Kaiserwerther Verband: it did not comment on it, but handed over the responsibility to the individual houses. One did not want to attract attention and, accordingly, behaved calmly.

Through the presentations by Benedikt Brunner on the semantic framework of “Volkskirche” in the Central German region, by Karsten Krampitz on the life of the pastor Wolfgang Staemmler, and by Dirk Schuster on the importance of the Eisenach “Entjudungsinstitut” (Institute for De-Judaization), the workshop received a broader thematic setting than the mere consideration of diaconal organizations and institutions. Such a broad view is necessary, as was reiterated in the closing words of David Schmiedel, speaking on behalf of the organizers. As opposed to the existence of one Protestantism, a variety of Protestantisms (28 regional churches, Lutherans, Reformed, United, German Christians, Confessing Church, middle, etc.) existed. Similarly, a wide variety of individuals with different motivations were behind the respective institutions. And in addition to theological arguments for or against motives for cooperation with representatives of the Third Reich, it was often profane reasons that played a crucial role for the respective attitude.

At the end of the workshop, the (recurring) debate concerning the distinction between theological anti-Judaism and racial anti-Semitism came up again. One contribution to the discussion put the finger on the problem when, in an ironic question, someone asked about the meaningfulness of such a distinction: Is a theological hatred of Jews better than a racially argued hatred of the Jews? From the perspective of the author of these lines, representatives of such a distinction often forget a crucial point. It was secondary to the social marginalization of Jews whether this was based on racial and/or theological arguments. Crucial was the stigmatization of the Jews, which made it possible for German society to endorse the persecution and deprivation of these people. As a supplement to the research outlook sketched by Manfred Gailus, the direct impact of anti-Semitic statements and actions of local church representatives should be more in the focus of future research. The presentations of this workshop have provided an important impetus.

[1] The paper was subsequently published as an article. Elena Kiesel, “Kinderpflege im göttlichen Auftrag. Das Diakonissen-Mutterhaus Cecilienstift in Halberstadt und sein Verhältnis zur Nationalsozialistischen Volkswohlfahrt (NSV),” in Sachsen und Anhalt. Jahrbuch der Historischen Kommission für Sachsen-Anhalt 29 (2017): 257–292.

[2] Christoph Picker, Gabriele Stüber, et. al. (eds.), Protestanten ohne Protest. Die evangelische Kirche der Pfalz im Nationalsozialismus, vol. 1+2 (Leipzig: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 2016).

As the second subtitle reveals (“an annotated documentation”), the book is a descriptive representation of the German Christian Church Movement with a regional focus on the origins of the movement in the Wieratal near the city Altenburg. In his presentation, the author outlines the development chronologically: first of all, he describes how the two young vicars, Siegfried Leffler and Julius Leutheuser, who were inspired by National Socialism, began scouring for a small circle of like-minded people from 1927 onwards. Within a few years, this small circle was to become one of the most influential inner-church movements that controlled several Protestant churches during the time of the “Third Reich”. The theological worldview of the church movement was a symbiosis of (Protestant) Christianity and National Socialism, since they saw the direct action of God in Adolf Hitler and his movement.

As the second subtitle reveals (“an annotated documentation”), the book is a descriptive representation of the German Christian Church Movement with a regional focus on the origins of the movement in the Wieratal near the city Altenburg. In his presentation, the author outlines the development chronologically: first of all, he describes how the two young vicars, Siegfried Leffler and Julius Leutheuser, who were inspired by National Socialism, began scouring for a small circle of like-minded people from 1927 onwards. Within a few years, this small circle was to become one of the most influential inner-church movements that controlled several Protestant churches during the time of the “Third Reich”. The theological worldview of the church movement was a symbiosis of (Protestant) Christianity and National Socialism, since they saw the direct action of God in Adolf Hitler and his movement. Lorenz’s goal is to compare New Testament passages from The Message of God with the Luther Bible, the standard translation, and the original Greek text. For this purpose, Lorenz has chosen three central terms by means of which she tries to analyze the new interpretation in The Message of God. Chapter 2 deals with the Messiah concept and the relationship between Jesus and Judaism. Chapter 3 places the concept of sacrifice at the heart of the comparison. Chapter 4 deals with the portrayal of Jesus in the New Testament traditions in comparison with Jesus’ presentation in The Message of God. The focus on concepts rather than merely on individual passages is very welcome, since, for example, in dealing with the Messiah concept, the entire Christology of The Message of God and thus of the German Christians can be derived, as Lorenz rightly states (83).

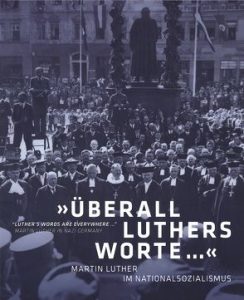

Lorenz’s goal is to compare New Testament passages from The Message of God with the Luther Bible, the standard translation, and the original Greek text. For this purpose, Lorenz has chosen three central terms by means of which she tries to analyze the new interpretation in The Message of God. Chapter 2 deals with the Messiah concept and the relationship between Jesus and Judaism. Chapter 3 places the concept of sacrifice at the heart of the comparison. Chapter 4 deals with the portrayal of Jesus in the New Testament traditions in comparison with Jesus’ presentation in The Message of God. The focus on concepts rather than merely on individual passages is very welcome, since, for example, in dealing with the Messiah concept, the entire Christology of The Message of God and thus of the German Christians can be derived, as Lorenz rightly states (83). The first part of the catalog impressively illustrates the instrumentalization of Luther as the “German faith hero” in the first two years of the Third Reich by using photographs and covers of contemporary publications. Several Protestant representatives drew an additional historical and theological continuity line from Luther to Hitler. Publications and celebrations such as the 450th anniversary of the reformer in 1933and the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Bible translation in 1934 illustrate the reference to Luther at this time. Likewise, many new church buildings were named after the reformer, the most well-known example being the Martin Luther Memorial Church in Berlin-Mariendorf, consecrated in 1935. On the theological level, in the early years of the Nazi regime, Luther’s doctrine of the two kingdoms was the center of church-political debates concerning the relationship between the church and the state. But this was increasingly changing in the mid-1930s. As a result of the exclusion of the Jews forced by the National Socialists, Luther’s antisemitic “Jewish writings” were increasingly placed at the center of the reformer’s reception. These writings often served as justification for the persecution of the Jews from a theological point of view. It is somewhat surprising that the section on the state-church relationship is mainly related to the view of the National Socialists, Bonhoeffer, Niemöller, and other representatives of the Confessing Church. The German Christians with their theological line of continuity of Jesus-Luther-Hitler are hardly mentioned in this section.

The first part of the catalog impressively illustrates the instrumentalization of Luther as the “German faith hero” in the first two years of the Third Reich by using photographs and covers of contemporary publications. Several Protestant representatives drew an additional historical and theological continuity line from Luther to Hitler. Publications and celebrations such as the 450th anniversary of the reformer in 1933and the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Bible translation in 1934 illustrate the reference to Luther at this time. Likewise, many new church buildings were named after the reformer, the most well-known example being the Martin Luther Memorial Church in Berlin-Mariendorf, consecrated in 1935. On the theological level, in the early years of the Nazi regime, Luther’s doctrine of the two kingdoms was the center of church-political debates concerning the relationship between the church and the state. But this was increasingly changing in the mid-1930s. As a result of the exclusion of the Jews forced by the National Socialists, Luther’s antisemitic “Jewish writings” were increasingly placed at the center of the reformer’s reception. These writings often served as justification for the persecution of the Jews from a theological point of view. It is somewhat surprising that the section on the state-church relationship is mainly related to the view of the National Socialists, Bonhoeffer, Niemöller, and other representatives of the Confessing Church. The German Christians with their theological line of continuity of Jesus-Luther-Hitler are hardly mentioned in this section.