Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 30, Number 4 (Winter 2024)

Conference Report: Christianity and National Socialism in International Perspective, Washington, October 2024

By Kevin P. Spicer, Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Andrew Kloes, Victoria Barnett, Kathryn Julian, and Jonathan Huener

The conference “Christianity and National Socialism in International Perspective” was co-organized by the Programs on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte/Contemporary Church History; and the Contemporary Church History Quarterly. It was held from October 2 – 4, 2024, at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Session 1

Kevin P. Spicer, C.S.C., Stonehill College, Moderator

Martin Menke, Rivier University: French are Catholics, Poles are Slavs: German Catholic Views of Their Neighbors, 1900-1945

Dirk Schuster, University of Vienna: The German Christian Movement in Austria and Romania, 1933-1945

Based on published and archival sources from the period, such as Abendland, Hochland, Center Party publications and Center-related newspapers, Reichstag proceedings, and government records, Martin Menke’s paper compared the development of German Catholic views of France and Germany, mainly during the interwar period. While German Catholics considered French Catholics to be brothers and sisters in faith and co-heirs to the realm of Charlemagne, they considered Poles to be Slavs first and ignored the Poles’ strong Catholicism. While this perception of the French helped to overcome postwar animosity, the pre-1914 defense of Polish rights by the Center Party evaporated during the struggles over Upper Silesia.

Dirk Schuster’s paper examined the impact of the German Christians Eisenach Institute for Research and Elimination of Jewish Influence on German Church Life on the Protestant churches in Austria and Romania. In both countries, the Protestant churches were a religious minority, and already in the 1920s, they experienced a decisive turn towards National Socialism. The national church in Romania was a stronghold of conservative elites. Younger church representatives rebelled against this situation and joined forces with the National Socialists. Due to various scandals, high church levies, and a widening gap between clergy and laity, many younger pastors and theologians took advantage of the momentum of National Socialism. They ousted the conservative elites from the church leadership. In Austria, the massive turn to National Socialism followed Austrian fascism’s rise after 1932 but did not impact the church in the same manner.

In 1939, the German Christians established the Eisenach Institute. The degree of radicalization of the national churches impacted the outreach of the Eisenach Institute. In Romania, young pastors without advanced theological training made up the majority; thus, advanced scholarly research was impossible. Instead, the clergy regularly adopted the output of the Eisenach Institute, such as a de-Judaized Bible and hymnal. The use of these texts continued even after the war ended. In many ways, the Protestant church in Romania became a testing ground for implementing such publications.

In Austria, the German Christians did not experience the same influence. We know of only six parishes in which the de-Judaized Bible was introduced after 1941. The Protestant Theological Faculty situation was completely different, as ethnonationalism permeated their teaching and scholarship. In turn, these academics eagerly embraced the “scholarship” of the Eisenach Institute and willingly collaborated with it.

Session 2

Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Simon Fraser University, Moderator and Respondent

Mark Ruff, St. Louis University, “Auxiliary Bishop Johannes Neuhäusler and his efforts to free convicted Nazi war criminals”

Suzanne Brown-Fleming, USHMM, “‘Love and Mercy’ after the Holocaust: The Vatican’s Postwar Clemency Campaign, 1945-1958”

Christopher Probst, Washington University in St. Louis, Continuing & Professional Studies, “Feindesliebe, ‘The Guilt of Others’, and the Jewish Question: Württemberg Protestant Clergy Coming to Terms with the Past”

These were three fine papers, each highlighting the roles of individuals in the immediate post-war era who worked within a world defined by crushing wartime defeat – the second in a generation – and all that entailed: a literally destroyed homeland; millions dead, wounded and missing; a Europe in ruins and dominated by the implacable ideologies of liberal democracy from the west and Soviet-style communism from the east. Many Germans, especially those with backgrounds like the subjects in these papers, had distrusted or feared both of these ideologies for decades. All three papers focus on individuals navigating courtrooms and judges and perpetrator-defendants, and questions about guilt and punishment and mercy. There seemed to be a shared understanding among them that the bad guys were not the Germans in the dock or in prison, but the Allies (read: the Americans), who at best were misguided and ignorant of what Germans had come through under Nazism and war, or at worst were hypocritical and vengeful.

I am struck that all three papers offer compelling evidence of continuity: the so-called “Stunde Null” of 1945 does not hold much weight in these accounts. Suzanne Brown-Fleming’s use of the recently-opened Vatican archives to investigate the involvement of Pope Pius XII and his “officers” – what she terms the “triumvirate” of Pius XII; Giovanni Battista Montini, later Pope Paul VI; and Domenico Tardini, later Secretary of State under John XXIII — in attempts to gain clemency for convicted war criminals provides evidence of, among other persistent traits, both latent and manifest antisemitism in the Holy See. Her findings mirror other scholars who have also gained access to these documents, notably David Kertzer in his portrayal of the wartime papacy. Mark Ruff’s presentation of Bishop Johannes Neuhäusler highlights the persistence of certain traditions in Catholic moral theology: there is no sin too big that may not be forgiven; the spiritual journeys of all Christians but evidently especially perpetrators must be encouraged and supported by God’s representatives on earth (i.e. priests). I found this resonant with my own research more than a decade ago, when priests and seminarians in the military used multiple ways of justifying their service in the Wehrmacht, but ultimately they claimed that they were all part of the same chorus: the men with whom they were serving (not so much those on the receiving end of the Wehrmacht’s attentions) had great need of them. Christopher Probst tells of Ebersbach pastor Hermann Diem’s devotion to love above all else, even of one’s enemies, and of the fierce national devotion of Theophil Wurm, chairman of the Protestant Church Council in Germany, which led him to intercede on behalf of mass murderers like Einsatzgruppe leader Martin Sandberger.

The worldview to which our protagonists adhered left little room for any other kind of victim: Jew, Romani, communist, Slav. Christopher presents what may be an anomaly in this context, in the example of Diem, who helped to hide Jews during the Shoah as part of a Württemberg “rectory chain” and whose postwar sermons emphasized accountability, responsibility, and a condemnation of evil in all its forms through a kind of ferocious love. Apart from Diem, we are treated to an array of individuals displaying stalwart German nationalism or, to clarify the motivations of the Italians in Brown-Fleming’s presentation, a “brotherly understanding”; both nationalism and understanding (what we might otherwise call sympathy) led these individuals to agitate on behalf of convicted criminals who had said reprehensible things (the antisemite Gerhard Kittel) or who had facilitated or perpetrated war crimes or crimes against humanity (the SS leaders Oswald Pohl and Otto Ohlendorf; the foreign minister Konstantin von Neurath; the navy admiral Erich von Raeder; the field marshal Wilhelm List). In their view, these were good Christian men who had either (1) made mistakes that they now repented, (2) had simply followed orders, or (3) were perhaps guilty of some charges, but of far greater concern were the alleged abuses and irregularities of the American prosecutors. Of course, the three exonerative appeals could operate conveniently in tandem.

Such evidence leads us to agree with our presenters’ conclusions that, once more, Christian moral theology in the 1940s and early 1950s consistently enabled its adherents to advocate on behalf of those co-religionists that they viewed were most in need of their support, and that it was easier to encourage an affinity/sympathy with a “sorrowful” Christian perpetrator (and the extent of the sorrow is debatable) than with the perpetrator’s victim – many of whom were dead and therefore absent anyway. There was a time when I would have cast this kind of moral theological thinking as falling short of true Christian aims. But as I’ve become immersed in this particular history, I think these papers raise the question whether we, in the 21st century, should continue to expect Christian leaders in the 1940s to have behaved otherwise, given the framework within which they had been raised and trained. Diem is the example that we wish was the standard, but instead he is the anomaly perhaps because he broke with tradition to articulate what he saw as the more pressing needs of his day, even if it went against his upbringing. I wonder if he recognized this, and felt like an outsider, even as he stood (somewhat alone) on the strength of his convictions.

Session 3

Andrew Kloes, USHMM, Moderator and Respondent

Andrea Strübind, Oldenburg University: “Baptists and the Persecution of Jews and Christians of Jewish Origin under the National Socialist Dictatorship”

Sandra Langhop, “Between Obedience and Resistance: The Basel Mission in National Socialism”

The second day of the conference began with presentations by two scholars from the Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg in Lower Saxony. Professor Dr. Andrea Strübind spoke on “Baptists and the Persecution of Jews and Christians of Jewish Origin under the National Socialist Dictatorship.” In her paper, Strübind analyzed “central themes in Christian anti-Semitism and racist anti-Semitism in Baptist churches, as well as their conduct towards the Jewish-Christian members and office holders in response to the measures promoted by the National Socialist regime to persecute Jews.” Strübind emphasized during her remarks that she approached this topic as a historian and as Baptist pastor in the Bund Evangelisch-Freikirchlicher Gemeinden in Deutschland. As an introductory focus, Strübind discussed the poignant case of Josef Halmos, who was a Jewish convert to Christianity and the member of a Baptist congregation in Munich. As a Sunday school teacher, Halmos was well-acquainted with the family of the pastor, Heinrich Fiehler, whose son, Karl Fiehler, served as the Lord Mayor (Oberbürgermeister) of Munich from March 1933 through May 1945. Drawing upon entries from Halmos’ diary, Strübind was able to demonstrate that the Fiehlers and other members of the congregation, of which he had long been an active member, enthusiastically embraced National Socialism and concomitantly ostracized Halmos because of his Jewish background. Strübind convincingly argued that, while Baptists numbered only about 70,000 in Germany and were thus one of the smallest churches, the history of their response to the Nazi regime after January 1933 generally mirrored those of the much larger Protestant and Roman Catholic Churches. “Some Baptists hid Jews and Jewish Christians. Many did recognize that the planned destruction of the ‘people of the Covenant’ increasingly bore the signs of diabolical rule in Germany and that this would lead to a catastrophe. A few theologians expressed this apocalyptic thought in words in their sermons and addresses. But nothing was officially mentioned nor was there any sort of petition made to the authorities.” Strübind concluded by discussing the current efforts of Baptists in Germany to memorialize those members of their congregations who were abandoned during the Holocaust, including Josef Halmos, who was murdered at Auschwitz.

Sandra Langhop, a Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin at the Institut für Evangelische Theologie und Religionspädagogik of the Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg, presented a paper based on her ongoing doctoral research into the Basel Mission during the National Socialist period. Citing a June 1933 article published by Karl Hartenstein, a Universität Tübingen graduate and the German director of this Swiss missionary society, Langhop was able to show persuasively that National Socialist thinking had become influential among some German-speaking Protestant missionaries. Hartenstein wrote in his society’s periodical, Der Evangelische Heidenbote: “We can never thank God enough that he once again had mercy on our Volk. After years of great despair, he gave us new hope for our Volk and our Reich. He sent us a real Führer after the times of great confusion… He pulled our Volk back from the abyss of Bolshevism at the last moment. He made our Volk united… as hardly ever before in its history. He has begun a cleansing process with us, in which everything rotten and corrupt from years ago has been broken open and can be swept out.” Langhop further analyzed how völkisch thinking variously shaped certain Basel missionaries’ approaches to their work in India, vis-à-vis British colonial government officials and indigenous peoples, and between German and Swiss missionaries.

One theme that connected both papers was their analysis of the positive reception with which many Christian churches and Christian organizations in Germany welcomed National Socialism in 1933, believing it to be a preferable to both Weimar era-democracy and communism. Secondly, both papers demonstrated how, despite the historic bonds that had long connected them to Protestants in other countries, German Baptists and German missionary supporters adopted identities that emphasized their belonging to the German people and eschewed alternative conceptions of self that were international in nature, such as belonging to the global Christian community or to the spiritual body of Christ.

Dr. Andrew Kloes is an applied researcher in the Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The views expressed here are the those of the author and do not represent those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Session 4

Victoria Barnett, University of Virginia, Moderator and Respondent

Blake McKinney, Texas Baptist College: “The Selberg Circle and Transatlantic Propaganda”

Friedericke Henjes, Oldenburg University: “The Reception of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in Anti-Semitic Conspiracy Theories on the Internet”

These two papers cover different eras and topics—but their underlying theme (the dynamics of propaganda) led to an illuminating discussion.

Blake McKinney discussed a little-known pro-German group in the United States, led by an American businessman, Emil Selberg, that pushed Nazi propaganda during the 1930s. Selberg was sympathetic to post-1918 German resentments, including the view that the Versailles Treaty had placed an impossible burden on the German people, whose resentment and anger led them to see Adolf Hitler as a leader offering new hope.

Selberg wanted to promote a positive image of the new regime in the United States. His allies were U.S. Senator Royal Copeland from New York and a prominent Methodist layman, Paul Douglass (who later became president of American University). Copeland suggested early on that Selberg might find a receptive ear for his work in American churches, including staff members at the Federal Council of Churches in New York who were focused on promoting reconciliation with Germany after the First World War.

Selberg’s main point of contact in Berlin was August Wilhelm Schreiber, an official in the Church Federation office. Both men seem to have seen this as an opportunity to advance their own careers. Having a high-ranking church contact in Berlin gave Selberg an entry point to the FCC staff. In turn, an important American church contact made Schreiber useful, both to the Deutsche Christen as they sought to create a new Reich Church and to the Nazi regime, which was already creating propaganda aimed at the U.S. McKinney’s research offers some insight into why, by the end of 1933, FCC officials like Henry Leiper were backpedaling from their early forthright condemnations of German church silence about Nazi measures to a “both-sides” approach, as they navigated the divisions within German Protestantism.

Ultimately, Selberg’s attempts were sidelined by the events of the Church Struggle itself and growing international outrage at Nazi policies. Adolf Hitler abandoned the Reich Church project in October 1934 because of the domestic and international backlash. In the United States, there was growing attention (much of it focused on Martin Niemoeller and the Confessing Church) to what people saw as the Nazi persecution of Christians. Copeland and Douglas, however, continued to defend the “new Germany” throughout the 1930s, and Douglas even published a book in 1935, God Among the Germans, which gave a sympathetic picture of Nazi Germany and the Deutsche Christen.

McKinney’s research provides an interesting new piece of the puzzle in our understanding of international Protestant reactions to the events unfolding in Nazi Germany. It is also a revealing glimpse of German and American cooperation in spreading propaganda on behalf of National Socialism, long before the rise of the internet.

The Russian antisemitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion also reached a worldwide audience in the pre-internet era, but as Friedericke Henjes’ paper illustrated, modern social media has brought it to new audiences. The most striking aspect of her research is that the Protocols itself is no longer even necessary. Its message has been incorporated into modern conspiracy theories.

The Protocols is a case study in how conspiracy theories spread because of underlying prejudices. As Henjes noted, even in the 1930s the Protocols were recognized as a forgery—but in a conspiracy theory, the truth doesn’t matter. What matters is how the conspiracy theory is used to explain popular resentments about world events. The Protocols did this by drawing on the long history of Christian anti-Jewish tropes and their historical legacy in terms of “otherizing” Jews through various anti-Jewish legal restrictions, etc. The dog whistles have not changed since the first copy of the Protocols appeared, for example: the “wandering Jew” who infiltrates society leading to the collapse of moral standards, and the conviction that there is a secret society of “Jewish bankers” who manipulate world history.

Henjes explores how these prejudices dovetail neatly with more modern dog whistles about “globalism,” the purported influence of George Soros, etc. The core of her argument is that “the content of the ‘Protocols’ is largely disseminated on the internet via the keywords and antisemitic narratives they contain.” She offered two modern examples from two activists in the German anti-vaccine movement: Attila Hildman and Oliver Janich. Hildman literally quotes the Protocols but links its various antisemitic tropes to recent developments like the Covid pandemic and the anti-vax movement. Janich does something similar, tying the Protocols to current issues, quoting the Gospel of John, and promoting conspiracy theories.

As Henjes notes, many modern conspiracy theories may not immediately be recognized as antisemitic—but they share a common language with the Protocols, now over a century old. Even without using the actual text of the Protocols, there are numerous slogans and images in the digital ecosystem that convey antisemitism and incite violence against Jews.

Session 5

Kathryn Julian, USHMM, Moderator and Respondent

Katharina Kunter, University of Helsinki: “Anne Frank in Frankfurt: Entangling the Holocaust, Local Memory and Civil Education”

Björn Krondorfer, Northern Arizona University: “The Sound of Evil: Imagining Perpetrators”

Carina Brankovic, Oldenburg University, “Conceptions of Remembrance in Leyb Rochman’s Chronicle of Survival”

In all three of these projects, there’s an interplay between intersecting memory cultures: international/ globalized memory, national/ local, civic/ confessional. Each panelist discussed how the subject changed depending on the context in which a text or memorial is being read, watched, or listened to, which indicated how memory culture can be politicized and also find interesting overlaps between various groups. For instance, Katharina discussed how the memory of Anne Frank evolved in Frankfurt in response to both international and local politics, from Adenauer’s conservative West Germany of the 1950s to a reunified Germany that emphasized humanitarianism to a more recent globalized vision of Anne Frank. There were a variety of global connections that could be made about Katharina’s project (e.g. how the memory of Sadako Sasaki has been used in the same way in Hiroshima and in global peace movements). In all three projects, there could be important interventions if discussed in a global context.

Historicization and temporality was also incredibly important in each of these talks. They showed that engagement with Holocaust memory is vastly different whether the 1950s, 1989/ 90, or in 2024. Carina, for example, showed how Leyb Rochman’s chronicle was read and reimagined in the immediate postwar period by the survivor generation as a yizkor book and memorial vs. how his writing was read by the second generation and implications for the future. In this same vein, Björn discussed how silence was used in the 2023 film Zone of Interest. He contended that this film in its omission of violent imagery was even more chilling to audiences in 2023, because what occurred during the Holocaust and at extermination camps has long been established in public memory and discourse. Each of these papers illuminated how Holocaust memory continues to be interpreted and reimagined in a variety of temporalities, civic, and religious contexts, whether in museums, local education, texts, film, or even in quotidian interactions.

Session 6

Jonathan Huener, University of Vermont, Moderator and Respondent

Rebecca Carter-Chand, USHMM, “The Historical Turn in Interpreting Rescue during the Holocaust: Reevaluating Religious Motivations and Religious Networks”

Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University, “Bending Christianity to Far-Right Politics in Nazi Germany”

The final session was devoted to presentations by Dr. Rebecca Carter-Chand, Director of Programs on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust at the USHMM, and Dr. Kyle Jantzen, Professor of History at Ambrose University. The session was a fitting capstone to the conference, as both papers encouraged reconsideration of conventional approaches to church history in the Nazi era, even as they proposed new avenues of inquiry.

Carter-Chand’s contribution, “The Historical Turn in Interpreting Rescue during the Holocaust: Reevaluating Religious Motivations and Religious Networks,” began with a historiographical overview emphasizing that traditional analyses have tended to focus on the individual rescuer’s motives, personality, courage, and sacrifice. Carter-Chand, however, encourages a redirection in the scholarship away from rescue as a psychological phenomenon and toward rescue as a historical phenomenon, focusing more on circumstances and context in the form of “structural” and “situational” factors – factors that might include landscape, victim and rescuer networks, or the nature of occupation and coercive state power in a given setting. As an illustration, Carter-Chand concluded with a brief video interview with Holocaust survivor Zyli Zylberberg, inviting consideration of what contextual factors moved Zylberberg to make the choices she did, and how we are to evaluate her own personal agency in the complex process of rescue.

Kyle Jantzen’s presentation, “Bending Christianity to Far-Right Politics in Nazi Germany,” also offered a novel approach in our attempt to understand the place of the churches and Christianity in Nazi Germany. Reflecting on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s essay “After Ten Years,” Jantzen urged consideration of how the current growth of Christian nationalism and the so-called “culture wars” might help us in understanding the churches during the Third Reich. We are accustomed to drawing upon the lessons of the past to inform the present, but Jantzen suggested an inversion of sorts, that is, letting the challenges of the present inform our approach to the churches in the Nazi era, considering broadly how Christianity and its institutions adapt to politics and, more precisely, the “bending” of Christianity to the politics of the right. For Jantzen, this “bending,” both in Nazi Germany and in the present, is to be understood not in static or linear terms, but as a complex dynamic process, often improvised and experimental. Moreover, Jantzen emphasized that, in attempting to understand this process, we need to “look to the middle,” that is, between the categories of support, compliance, and defiance, and to local contexts.

But as Tim Lorentzen’s new book illustrates, it is hardly the first time that interpretations of Bonhoeffer have been based on his ties to the German resistance. Lorentzen, Professor of Early Modern Church History at Kiel University, traces the chronology of German cultural narratives about Bonhoeffer’s resistance, and their intersections with German Protestant memorialization, from 1945 to 2006. His focus on resistance (rather than German historiography about Nazism, the Holocaust, the Protestant Kirchenkampf, or Bonhoeffer’s theological writings) is a narrow lens through which to understand Bonhoeffer, but it raises interesting and provocative questions. As historians know, Bonhoeffer was a minor figure in the resistance circles—and yet this very aspect of his life has become central in the narratives about him. Would Bonhoeffer’s theology be as well-known and widely read today if this were not the case? Has the emphasis on resistance led to the historical distortions one finds in many works on Bonhoeffer? Conversely, does it offer insights we might not otherwise have into his theology and his life?

But as Tim Lorentzen’s new book illustrates, it is hardly the first time that interpretations of Bonhoeffer have been based on his ties to the German resistance. Lorentzen, Professor of Early Modern Church History at Kiel University, traces the chronology of German cultural narratives about Bonhoeffer’s resistance, and their intersections with German Protestant memorialization, from 1945 to 2006. His focus on resistance (rather than German historiography about Nazism, the Holocaust, the Protestant Kirchenkampf, or Bonhoeffer’s theological writings) is a narrow lens through which to understand Bonhoeffer, but it raises interesting and provocative questions. As historians know, Bonhoeffer was a minor figure in the resistance circles—and yet this very aspect of his life has become central in the narratives about him. Would Bonhoeffer’s theology be as well-known and widely read today if this were not the case? Has the emphasis on resistance led to the historical distortions one finds in many works on Bonhoeffer? Conversely, does it offer insights we might not otherwise have into his theology and his life? The film, which is beautifully shot and scored, but at times laden with clunky dialogue, begins with a glimpse into the domestic life of the Bonhoeffer family (warm and loving, and also tranquil until Dietrich’s beloved older brother Walter is killed in the Great War). Yet it largely focuses on Bonhoeffer’s involvement in a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, who became chancellor of Germany in 1933. The film flashes back and forth, from Bonhoeffer’s imprisonments in Buchenwald and Flossenbürg to the years preceding the war. It tells the tale of a young theologian whose participation in the 1944 plot to assassinate the Führer and overthrow the Nazi regime seems nearly inevitable. The flashbacks often muddle both the chronology and the film’s interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s de-contextualized words.

The film, which is beautifully shot and scored, but at times laden with clunky dialogue, begins with a glimpse into the domestic life of the Bonhoeffer family (warm and loving, and also tranquil until Dietrich’s beloved older brother Walter is killed in the Great War). Yet it largely focuses on Bonhoeffer’s involvement in a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, who became chancellor of Germany in 1933. The film flashes back and forth, from Bonhoeffer’s imprisonments in Buchenwald and Flossenbürg to the years preceding the war. It tells the tale of a young theologian whose participation in the 1944 plot to assassinate the Führer and overthrow the Nazi regime seems nearly inevitable. The flashbacks often muddle both the chronology and the film’s interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s de-contextualized words.

Breger rightly notes that following World War II, neutrality had a negative connotation and was often seen as a form of collaboration with the Nazis. Countries like Switzerland, and to some extent Sweden, did not emerge from the war with their reputations fully intact. Consequently, for many years, Vatican neutrality has received little attention in academic literature. This volume, which spans from 1870 to 2020, helps to close that gap by examining various aspects of the Vatican’s neutrality over these 150 years. However, the main focus is on the Vatican’s neutrality as defined in the Lateran Pacts of 1929, which also established the city-state. Breger states the goal of the project thus: “This book will consider the interplay between two normatively disparate subjects – the concept of neutrality in international law and the concept of the Vatican as a neutral actor in international relations” (Breger xii). This review will provide a general overview of the volume, highlighting a selection of the thirteen essays rather than examining each one in detail. I will focus primarily on essays that fall more closely in my own research purview, which deals with Fascism, WWII and the immediate postwar years.

Breger rightly notes that following World War II, neutrality had a negative connotation and was often seen as a form of collaboration with the Nazis. Countries like Switzerland, and to some extent Sweden, did not emerge from the war with their reputations fully intact. Consequently, for many years, Vatican neutrality has received little attention in academic literature. This volume, which spans from 1870 to 2020, helps to close that gap by examining various aspects of the Vatican’s neutrality over these 150 years. However, the main focus is on the Vatican’s neutrality as defined in the Lateran Pacts of 1929, which also established the city-state. Breger states the goal of the project thus: “This book will consider the interplay between two normatively disparate subjects – the concept of neutrality in international law and the concept of the Vatican as a neutral actor in international relations” (Breger xii). This review will provide a general overview of the volume, highlighting a selection of the thirteen essays rather than examining each one in detail. I will focus primarily on essays that fall more closely in my own research purview, which deals with Fascism, WWII and the immediate postwar years. Christian internationalism has yet to find a secure place in the various histories of twentieth-century churches. Very largely this is due to a persistent emphasis on national categories and narratives, but denominational perspectives have also fashioned a great deal of what we expect to find in the foreground. All too often, Bell and Oldham may be observed, usually dutifully and briefly, hovering in the background of anything other than ecumenical surveys. In the final volume of the recent Oxford History of Anglicanism (OUP, 2019), Bell flits about here and there, but there is no very confident sense of where to put him for very long. Meanwhile, Oldham, the United Free Church layman, has almost vanished from ecclesiastical memory altogether. This is an authentic tragedy because it indicates how horizons have contracted across the western Protestant churches in the half-century since their deaths.

Christian internationalism has yet to find a secure place in the various histories of twentieth-century churches. Very largely this is due to a persistent emphasis on national categories and narratives, but denominational perspectives have also fashioned a great deal of what we expect to find in the foreground. All too often, Bell and Oldham may be observed, usually dutifully and briefly, hovering in the background of anything other than ecumenical surveys. In the final volume of the recent Oxford History of Anglicanism (OUP, 2019), Bell flits about here and there, but there is no very confident sense of where to put him for very long. Meanwhile, Oldham, the United Free Church layman, has almost vanished from ecclesiastical memory altogether. This is an authentic tragedy because it indicates how horizons have contracted across the western Protestant churches in the half-century since their deaths. After setting his agenda in the introductory chapter, Skiles outlines in Chapter 2 the religious conflicts under National Socialism, and more specifically, the division in German Protestantism between the German Christian movement, which sought to align Protestant theology and praxis with Nazi ideology, and the Confessing Church. For Skiles, at the foundation of that conflict was “a profound disagreement about the nature of divine revelation,” (p. 28) with the German Christians claiming to find divine revelation in history, national identity, and racial “science.” By contrast, the Confessing Church, in the spirit of the Reformation, held to the doctrine that knowledge of God is to be found in scripture alone. This chapter provides important context as it guides the reader through some of the early milestones in the regime’s conflict with the Confessing Church: the controversy over the “Aryan Paragraph” of 1933, which excluded clergy of alleged Jewish heritage from the pastorate; the subsequent formation of the Pastors’ Emergency League, which formed the basis for the Confessing Church; and the issuing of the Barmen Declaration in 1934. Skiles also effectively challenges in this chapter two common and simplified interpretations: that the Confessing Church was an anti-Nazi resistance group, and that the Confessing Church’s conflict with the regime was essentially about ecclesiastical freedom.

After setting his agenda in the introductory chapter, Skiles outlines in Chapter 2 the religious conflicts under National Socialism, and more specifically, the division in German Protestantism between the German Christian movement, which sought to align Protestant theology and praxis with Nazi ideology, and the Confessing Church. For Skiles, at the foundation of that conflict was “a profound disagreement about the nature of divine revelation,” (p. 28) with the German Christians claiming to find divine revelation in history, national identity, and racial “science.” By contrast, the Confessing Church, in the spirit of the Reformation, held to the doctrine that knowledge of God is to be found in scripture alone. This chapter provides important context as it guides the reader through some of the early milestones in the regime’s conflict with the Confessing Church: the controversy over the “Aryan Paragraph” of 1933, which excluded clergy of alleged Jewish heritage from the pastorate; the subsequent formation of the Pastors’ Emergency League, which formed the basis for the Confessing Church; and the issuing of the Barmen Declaration in 1934. Skiles also effectively challenges in this chapter two common and simplified interpretations: that the Confessing Church was an anti-Nazi resistance group, and that the Confessing Church’s conflict with the regime was essentially about ecclesiastical freedom.

Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism.

Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism. Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less.

Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less. The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

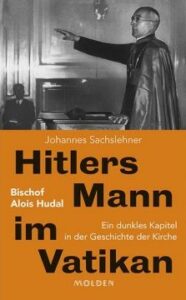

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position.

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position.