Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 30, Number 3 (Fall 2024)

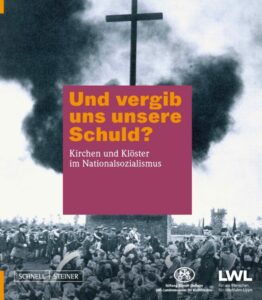

Review of Stiftung Kloster Dalheim, LWL-Landesmuseum für Klosterkultur, eds., Und vergib uns unsere Schuld? Kirchen und Klöster im Nationalsozialismus (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2024).

By Kevin P. Spicer, Stonehill College

The exhibition “And forgive us our sins? Churches and Monasteries under National Socialism” runs from May 17, 2024, to May 18, 2025, at the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim in Lichtenau near Paderborn. Founded by Augustinian canons in the fifteenth century, the Dalheim monastery was a victim of early nineteenth-century secularization and was used for regional agricultural purposes afterward. In 2002, the Westfalen-Lippe Regional Authority (LWL) transformed the ruins and grounds of the former Augustinian monastery into a state museum and created a permanent exhibition on monastic life and culture in 2007. Further renovations and provisions from 2008 to 2010 enabled the housing of additional exhibits, including “Churches and Monasteries under National Socialism.” I visited the exhibition in mid-July 2024, reaching it by rental car as public transportation was limited. This review will combine my experience of the exhibition and a review of the essays in its companion volume.

The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

The curators have organized the exhibit around ten questions. The companion volume follows this format and summarizes the exhibit’s content in an introduction and ten brief, well-cited essays. The companion volume is not a catalog, as it does not contain photos and descriptions of all the exhibit’s photos and items. Instead, it includes select images, vividly reproduced in considerable size, some covering two pages.

In the volume’s forward, Georg Lunemann, the chair of the Stiftung’s board of trustees and director of LWL, and Barbara Röschoff-Parzinger, chair of the Stiftung’s executive board and director of LWL’s cultural affairs, ask the question, “Is Christian faith and belief in National Socialism mutually exclusive?” According to them, the exhibit seeks to help its viewers answer this question by examining the interaction of both lay and ordained church members with the German state. They quote noted German historian Joachim Fest’s father, who originally wrote in Latin, “Even if everyone does it, I do not,” echoing Matthew 26:33. These words remind the visitor and reader of Fest’s resistance under National Socialism and “serve as a reminder and orientation for all of us not to become indifferent, but to face the challenges of our time with courage and knowledge of the past” (7). Indeed, the exhibition’s content endeavors to face the churches’ history under National Socialism with candor.

The Stiftung’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, authors the introductory essay, previewing and contextualizing the exhibit’s content. He points out that the exhibit seeks to aid a visitor to form an opinion about the churches under National Socialism but not to impose one. For him, the situation of the churches was “complex and ambiguous,” inviting the visitor and reader to realize that “we cannot use generalities to characterize the period.” He continues, “Few topics in contemporary history are so emotionally charged and simultaneously so controversial within a discipline. Few evoke such reflexive, morally weighted discussion compared to classical historiography, which first seeks to reconstruct historical events and then to fathom their causes” (10).

While the exhibition presents the history of both Christian traditions, even in the introduction, the curators portray Protestantism as more susceptible to National Socialism. Citing Hubert Wolf, Grabowsky explains that the Roman Catholic Church was the only institution under Nazi Germany that evaded Gleichschaltung (coordination) by which institutions collapsed together and Nazified. This exception allowed Catholicism to challenge the state from a unique position. The number of arrests or fines of members from the two traditions illustrates this point. Under National Socialism, we are told, nine hundred Protestant pastors and laity faced disciplinary action or arrest for faith-based activities compared to approximately 22,700 Catholic priests who endured the same fate. Still, the exhibit’s narrative and Grabowsky’s essay make us aware that reality is more complex than these numbers and, therefore, needs to be deeply studied. Ultimately, he reminds us that there is no unanimous historical opinion about the churches under National Socialism. Instead, we are invited to form views from the evidence presented.

A Stiftung researcher and staff member, Carolin Mischer, authored the first essay, “What was the situation in Germany before 1933?” Both the exhibit and Mischer’s essay well recall the Weimar Republic’s impactful events, such as the Versailles Treaty, reparations, the Weimar constitution, the Ruhr occupation, hyperinflation, the 1923 currency reform, the Golden ‘20s, the 1929 stock market crash, the government’s so-called presidential cabinets, the 1930 election with the NSDAP Reichstag representative increase, and Fritz von Papen’s machinations to promote Hitler. Numerous items representing the material culture of Weimar Germany accompany the exhibit. Most notable is an Electrola recording of Fritzi Massary singing “Jede Frau hat irgendeine Sehnsucht” (Every woman has a longing of some kind). Massary was an actress and singer who, in 1917, converted from Judaism to Protestantism. In 1932, because of antisemitism’s ascendency, she and her husband, the actor Max Pallenberg, left Germany for England, eventually moving to the United States. Her story reinforces the effect of the impact of Nazism’s blood-racial ideology – whereby conversion to Christianity did not alter an individual’s Jewish identity – on German society even before Hitler was appointed Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

An SS Julleuchter, a candle holder used in Winter Solstice festivals resplacing Christmas (p. 31).

Kirsten John-Stucke next asks, “What position did National Socialism take with Christianity?”, emphasizing that this relationship fluctuated over time as individual Nazis approached the churches differently, spanning the spectrum from collaborating with the churches to seeking to replace or destroy them. Hitler, she pointed out, wanted to coordinate the twenty-eight Protestant state churches under a central bishop. This internal effort ultimately failed under Reich Bishop Ludwig Müller. Next, attempting an external approach, in 1934 Hitler appointed Hanns Kerrl as Reich Church Minister for Church Affairs. He, too, was unsuccessful in unifying the various elements of Protestantism, which generally remained at odds with each other until 1945. Overall, the presentation on the state and Protestantism is convincing. However, the essay and the exhibit might have dug deeper to unpack the diversity among the personalities of the Confessing Church membership and the roles that nationalism and antisemitism played among them. Regarding the state and Catholicism, this exhibit’s section and John-Stucke’s essay primarily examine state-church interactions during seminal events such as the passing of the Concordat, the Oldenburg crucifix affair of November 1936, and the promulgation of the 1937 Vatican encyclical, Mit brennender Sorge. They also examine Martin Bormann’s June 1941 memo, which predicted a doomed vision of Christianity’s future in Germany, in which the churches were repressed, extinguished, and replaced by National Socialism. Both conclude with a fascinating examination of items related to National Socialism’s replacement rites and accompanying “sacramentals,” including a Julleuchter (Yule or Winter Candle) meant to be used in an ersatz Christmas celebration. The one on display and pictured in the companion volume was discovered in the house of a former Waffen-SS soldier. It was well used, complete with hardened wax droppings.

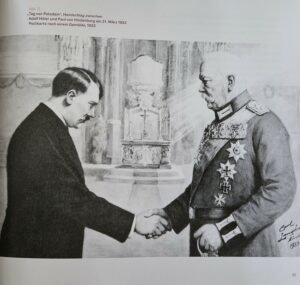

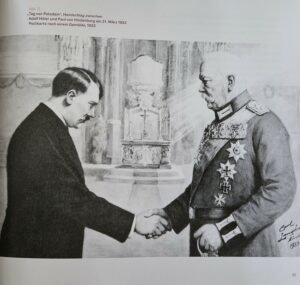

Adolf Hitler and Paul von Hindenberg, Day of Potsdam (p. 35).

Oliver Arnhold then asks the question, “Did Protestant Germany support National Socialism?” by centrally focusing on the infamous 1933 postcard depicting Chancellor Hitler in civilian attire bowing to President Paul von Hindenburg in a medal-covered military uniform. This portrait signified a hope to return to former values, restoring the throne and altar and the preeminence of Protestantism within the German state. Protestants accepted Hitler’s March 23, 1933, promise to make Christianity the foundation of his state. They did not protest the establishment of concentration camps or the gradual exclusion of Jews from German society. Arnhold clarified the complexity of Confessing Church members’ relationship to the state better than the previous essays, pointing out that, although they were opposed to the infiltration of the church by the state, most members did not oppose everything in National Socialism. Overall, Arnhold argues that most Protestants came to terms with National Socialism, and their Church institutionally never issued a public word against the state’s annihilative policies. Instead, in May 1939, their radicals founded the Eisenbach Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on Church Life.

Carolin Mischer makes a second contribution with the essay, “Was the Catholic Church an opponent or a partner of National Socialism?” To frame this question, she presents a chronological threefold model. At first, the Catholic hierarchy rejected National Socialism following the Mainz diocese’s 1930 decision to prohibit Catholics from being Nazi Party members. However, neither Misher nor the exhibit details the bishop’s varied stances on National Socialism. After 1933, the Church came to an arrangement with National Socialism following Hitler’s March 1933 promise to uphold Germany’s Christian nature and the 1933 Concordat’s signing. Misher and the exhibit emphasize that bridge-builders like the theologian Michael Schamus and church historian Joseph Lortz were in the minority. Both highlight the well-known controversy between historians Klaus Scholder and Konrad Repgen regarding the Concordat’s origins. Arrangement eventually led to defense as the state consistently infringed upon the Concordat’s demands, eventually leading to Mit brennender Sorge’s promulgation. Unfortunately, the exhibit and essay frame the encyclical as making more of a critique of the National Socialist racial ideology than it actually did historically. Likewise, both present Bishop Clemens von Galen as an opponent of euthanasia and entirely ignore his nationalistic and antisemitic worldview. Notwithstanding, both emphasize that the bishops, through their pastoral letters, supported the war and encouraged the Catholic faithful in their pastoral letters to be “loyal and obedient to the Führer” while never publicly protesting the persecution and systematic murder of Europe’s Jews. Misher concludes that “resistance to the National Socialist system was left to a brave few” (46).

Hubert Wolf covers the topic, “Did the pope remain silent?”, a theme he has been researching and writing extensively about. Both Wolf’s essay and the exhibit focus on Pius XII’s 1942 Christmas Address, which defenders point to as evidence of the Pope’s protesting the treatment of Jews. Wolf reveals that much of the speech, now missing from the Vatican Archives, was written by Gustav Gundlach, SJ. Nevertheless, most people did not interpret the pope’s words as condemning the systematic murder of Jews. Wolf concludes that the pope was ever so cautious, never even speaking out against the murder of millions of Poles, the majority of whom were Catholic. How, then, does anyone believe that he would condemn what has come to be known as the Shoah when he never bothered to condemn the mass killing of his own flock? Yet Wolf emphasizes that the pope was well informed about the treatment of Jews by nuncios, diplomats, bishops, and laity, Christian and non-Christian, and overwhelmingly through the thousands of letters he received asking for material assistance or emigration support. Wolf and his research team are currently engaged in research in the Vatican archives, organizing and digitizing these letters for an online database project. Overall, the pope remained neutral, writing in a February 20, 1941 letter to Matthias Ehrenfried, the bishop of Würzburg, “Unfortunately, where the Pope wants to speak out loudly, he must remain silent and wait; where he wants to act and help, he must wait patiently” (55). While the exhibit closely follows Wolf’s essay, some of its material culture seems misplaced for a historical exhibit, such as the inclusion of the graphic novel by Bernhard Lecomte, Un pape dans l’historie. Pie XII face au nazisme, vol. I (2020). Likewise, when the display asks, “Was the Pope silent?”, it refers visitors to the translated works of Saul Friedländer, John S. Conway, and Walter Laqueur, who examined this question long before the Vatican archives of this period were opened.

Sonja Rakocyz, a Stiftung researcher, next asks, “Were the churches and monasteries also victims of the regime?” Centering on the totalitarian claim of the German Führer state under National Socialism, both the essay and exhibit examine the areas in which the state directly attacked the churches. Both point to the currency and morality trials instigated by Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels and the confiscation of monasteries and church bells; the latter were melted down and turned into ammunition and other war-waging materials. Most important is the recollection of the often-forgotten story of Dominican Sister Brigitte Hilberling’s condemnation of the murder of Jews in occupied Poland, for which she was denounced and suffered months-long incarceration. Rakocyz concludes her essay by stating that the “churches and monasteries were victims of the National Socialist regime.” In particular, she views religious orders and monasteries as the regime’s “forgotten victims” (64).

The most critical essay, “Reflectance, Contradiction, Resistance?”, by Olaf Blaschke, questions the continued use of Kirchenkampf (church struggle) and Widerstand (resistance), explaining, “There was certainly not a Kirchenkampf, not a struggle of the National Socialist regime against the churches, and not a struggle of the churches against the National Socialist regime. Rather, there were only individual political measures and individual ecclesiastical countermeasures; by and large, there was a high degree of adaptation” (68). For Blaschke, viewing the churches as institutionally engaged in active resistance is incorrect. He is also not keen on using Martin Broszat’s term Resistenz, which denotes standing in the way, often unconsciously, of the total claims and machinery of National Socialism. Blaschke presents Klaus Gott and Hans Günther Hockerts’s fourfold resistance model, from “selective dissatisfaction” to “active resistance,” finding it unhelpful as 95% of Christians did not engage in resistance. Instead, he suggests a fourfold collaboration model, from “selective satisfaction” to “active collaboration.” Blaschke and the exhibit conclude that it was “characteristic of the period from 1933 to 1945 to be able to live both in consensus and contradiction” (74).

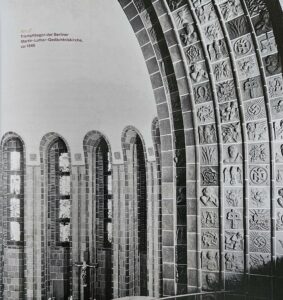

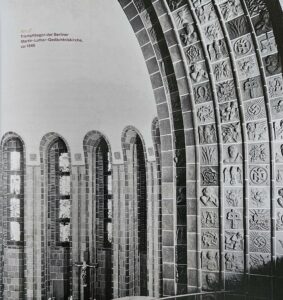

An image of ornamental tiles in the Martin Luther Memorial Church, Berlin (p. 77).

Sonja Rakoczy contributes a second essay, “Consensus, Cooperation, Complicity?”, by first highlighting the incorporation of Nazi symbols in church architecture under National Socialism, pointing to the Martin Luther Memorial Church in Berlin Mariendorf, nicknamed the “Nazi-Church.” The essay and exhibit use case studies of specific individuals to illustrate collaboration and complicity, including the Protestant, Abbess Emilie von Möller of Küne Abbey, and the Catholics, Abbot Ildefons Herwegen, OSB of Maria Laach; Father Johannes Strehl of St. Peter and Paul Parish in Potsdam; Father Lorenz Pieper; and Abbott Alban Schachleiter, OSB. Among the collaborators, both include the 1,300-plus military chaplains who supported the war effort by strengthening the soldiers’ morale and the parishes and congregations that benefited from slave labor. Most interesting is the case of the Kaufbeuren-Irsee sanitarium and nursing home staffed by the Mercy Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul, who fulfilled the demands of the euthanasia program by feeding their patients a low-nutrition diet to prepare them for transport to murder facilities. After seeking guidance on their participation in such unethical and deadly activity, they received assurance from the pro-Nazi auxiliary bishop Franz X. Eberle of Augsburg to continue the preparations for deportation, encouraging them to see them as a “charitable labor of love” (80). The exhibit reproduces Eberle’s letter in its entirety. Rakoczy concludes that there was a mixture of individual and selective institutional cooperation and participation among members of both Christian churches in the annihilative mechanisms of National Socialism.

At the root of National Socialist ideology was the ostracization and vilification of Jews. To this end, Andreas Joch, a Stiftung researcher, examines “How Christian is antisemitism?” His essay opens with a 1927 quote from Otto Dibelius, the General Superintendent of Kurmark within the Protestant Old Prussian Union, stating, “The Jewish Question is in the first place not a religious but a racial question. The portion of Jewish blood running through the body of our Volk is much higher than the religious statistics indicate” (84). Joch is determined to detach Christian anti-Judaism from antisemitism, writing, “This classification is crucial, as the antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries consciously distanced itself from older, religiously motivated forms of hostility towards Jews supported by the Christian church, which are summarized by the term anti-Judaism. Antisemitism no longer regarded Judaism as a religion but as a race. Christian beliefs were no longer to play a role in their rejection of Judaism” (84). While this may be the case, one must admit that there would be no antisemitism if Christianity had not first demonized Jews biblically and theologically. Joch never acknowledges this truth. For him, “antisemitism is an era-specific phenomenon” (89). Despite this stance, both Joch and the exhibit amply document the progression of anti-Jewish rhetoric and depiction over the centuries in a brief amount of space. In the end, Joch concludes, “It can therefore no more be assumed that Christian anti-Judaism continued to have an ‘unbroken effect’ than that antisemitism was eternal. However, this statement is by no means suitable for exonerating the Christian churches concerning their role in the National Socialist era” (89).

Sonja Rakoczy’s final essay, “Forgive and Forget?” examines the role of the churches in denazification and the ratlines, which facilitated the escape of wanted Nazi criminals. The exhibit presents various examples of Persilscheine, letters attesting to a clean political and social bill of health for individuals during the denazification processes. Persil was (and still is) a brand of laundry detergent, hence the snide whitewashing reference. Likewise, both her essay and the exhibit discuss the various efforts by church leaders to come to terms with the National Socialist past.

Despite my few critical observations above, the exhibition and companion volume successfully introduce the public to the question of the churches under National Socialism using a critical and well-argued approach. No one will leave the exhibition viewing the churches and their members as resisters who only battled the Nazi state. That myth is upended by the evidence presented. Instead, a visitor should understand the churches’ history under National Socialism through shades of grey, both good and evil as well as everything in between.

As is common among German-language works on the churches, no non-translated works by English authors are among the cited works. Perhaps this was done deliberately. The exhibit and companion volume do not include translations, though the museum provides visitors with a brief English-language handout. Both are meant for a German-speaking audience, inviting them to come to terms with Christianity’s choices and activities under National Socialism. Critics could easily dismiss any evidence referencing an English-language work as fundamentally biased and unfair. Instead, this exhibition created by and for Germans invites Germans to examine their churches’ past.

On the Sunday afternoon I viewed the exhibit, the audience consisted of individuals in their fifties and over – at least by appearance! I genuinely hope that all generations of Germans can see it.

Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism.

Chamedes summarizes the existing scholarship concerning the Church’s fight against communism and its willingness to collaborate with fascism. However, her insights about the fear of Western liberalism and materialism are novel and worth exploring further. For example, she cites Vatican archival records in which editor of the Code of Canon Law Eugenio Pacelli, future nuncio to Germany, Cardinal Secretary of State, and Pope, stated his fear that the U.S. entry into World War I was part of the campaign to secularize Europe. [2] The author argues that the Church perceived President Woodrow Wilson as determined to destroy the Church. As Chamades shows, the Church’s fear of liberalism lasted well beyond World War II. After World War I, the Church saw itself engaged in an existential struggle with liberalism, which explains its willingness to work with fascist regimes that opposed both liberalism as well as socialism. Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less.

Ten years later, Arnhold has published a condensed version of his doctoral thesis. In 245 pages, he tells the history of the establishment of the largest research institute in the Third Reich that dealt with the so-called “Jewish question”. Promoted by the Thuringian German Christian Church Movement (Kirchenbewegung Deutsche Christen), the institute was opened at Wartburg Castle in Eisenach – one of the most important places for Protestants –in May 1939 with the intention of tracing and eliminating all Jewish influences within (Protestant) Christianity. The aim was to prove – on its own initiative, without state influence, supported by various Protestant regional churches and with the collaboration of renowned professors – that Jesus of Nazareth, and with him Christianity as a whole, had always stood in extreme contrast to Judaism. Jews, however, had distorted the true message of Jesus, which the Eisenach Institute was to bring to light again. Accordingly, some of the staff also saw themselves as completing Luther’s Reformation. Luther had liberated Christianity from the papacy in the sixteenth century. Now, under the rule of the “God-sent Führer” Adolf Hitler, the time had come to accomplish in full Luther’s Reformation and remove all alleged Jewish influences from Christianity. The message of Jesus and, indeed, his entire person were to be “de-Judaized” (entjudet) – nothing more and nothing less. The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

The exhibition is well-crafted, offering a thorough and balanced introduction to the history of the Christian churches under National Socialism. At its entrance, a placard lists the curators under the leadership of the Stiftung Kloster Dalheim’s director, Ingo Grabowsky, and the scholarly advisors, Oliver Arnhold of the University of Paderborn; Olaf Blaschke and Hubert Wolf of the University of Münster; Gisela Fleckenstein and Hermann Großevollmer of the Paderborn Archdiocese’s Commission for Contemporary History; Kirsten John-Stucke of the Büren-Wewelsburg District Museum; and Kathrin Pieren of the Westfalen Jewish Museum. As our readers know, Blaschke and Wolf have written extensively about the churches under Nazism. The placard also contains an impressive and extensive list of archives, museums, and libraries, encompassing cities, towns, and institutions across Germany that contributed to the exhibit. Interestingly, there is no mention of Bonn’s influential Commission for Contemporary History or the participation of any of its academic board members.

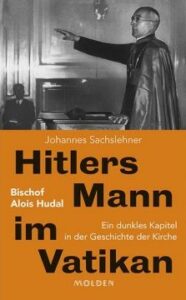

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position.

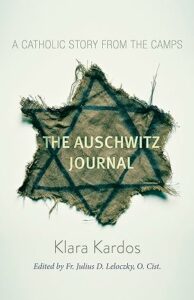

Sachslehner’s emphasis on Hudal’s early ambition, constant desire for recognition, and embarrassment over his heritage helps to explain both his career as well as his extreme commitment to German nationalism. Hudal’s contemporaries soon recognized his ambitions and accused him of sycophancy. Sachslehner suggests that this need for recognition contributed to Hudal’s völkisch and pro-National Socialist positions as well as his later commitment to a free Austria, even as he helped hunted war criminals to escape. Hudal grew up near Graz. Proving himself intelligent, he won scholarships to obtain a Catholic education, leading to his ordination in 1908 and to a doctoral degree in Old Testament Scripture in 1911. In 1914, the bishop of Graz sent Hudal to the Anima in Rome to continue his studies. Such appointments were considered a stepping stone to higher office in the Austrian church. Hudal helped to ensure that the leadership of the parish and the institute remained in Austrian hands despite German diplomatic efforts to change that. At the time, Hudal believed his only suitable further promotion was to the episcopal seat at Graz, whereas his bishop believed a university post in Graz was a sufficiently dignified position. Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true.

Much like Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, in which Frankl made a conscious decision to fight to retain his humanity against all odds, Klara Kardos’ story features a similar decision. In Kardos’ case, though, her prayer life and her way of framing her persecution allowed her to detach herself from the day-to-day horrors she was experiencing. When Kardos was deported from the Szeged ghetto to Auschwitz, her spiritual director (a priest not named in full in the account) wrote of her walking to the deportation train as a “deportee of heroic spirit… with a triumphant smile on her face for the road of sufferings. Will she ever return to Szeged? Only God can say. We can only hope. But her heroic spirit that was shining from her soul showed the world that the soul, even in a body trampled underfoot, in the midst of ignominy, can be victorious over her oppressors…” (42). Kardos humbly remarks that the priest’s words were very idealistic, but she also confirms that the essence of his words describing her departure were true.