Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 19, Number 3 (September 2013)

Conference Report: Reassessing Contemporary Church History, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, July 25-27, 2013

By Mark Edward Ruff, St. Louis University

This three-day conference brought twenty scholars from Canada, the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany to the campus of the University of British Columbia on the shores of Vancouver Bay to take stock of the current state of German church history in the 20th century, plot out the future direction for the new electronic journal, Contemporary Church History Quarterly and to honor the eighty-three year old Anglo-Canadian scholar and pioneer in the field, John Conway.

The keynote address from Thursday evening, “The Future of World Christianity” was delivered by Mark Noll, Professor of History at the University of Notre Dame. In his hour-long presentation, Noll contrasted the situation of Christianity in the Western and non-Western worlds for the years 1910 and 2010. Christianity has exploded numerically in Africa, Asia and Latin America, eclipsing its presence in what had at just a century earlier had been its European heartland. Noll began by highlighting the dramatic scope of recent changes. In 1970, there had been no legally open churches in China in 1970; China may now have more active believers attending church regularly than does Europe. Noll argued that it was raw life-and-death struggles of poverty, disease, tribal warfare, social dislocation, and economic transformation that help explain this surge in religiosity outside of the western world. He urged historians of Christianity to learn more about the work of African prophet-evangelists of the early 20th century like William Wadé Harris and Simon Kimbangu instead of focusing exclusively on better-known western theologians and churchmen.

Friday’s proceedings were divided into three distinct panels. The first, “The Changing Historiography of the Church Struggle, 1945 – 2013” highlighted the changing hermeneutics, value-systems, theological categories and historical methodologies that have been employed to instill meaning into the struggles of the churches against the National Socialist state. Mark Edward Ruff’s paper, “The Reception of John Conway’s, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches” analyzed why Conway’s pioneering work evoked profoundly different reactions in the English-speaking world and in the Federal Republic of Germany. In the Anglo-American world, it garnered praise; in Germany, it was largely met with criticism or indifference. Ruff argued that the very factors that ensured its mostly positive appraisals in the United States guaranteed its harvest of criticism and silence in Germany from those professional historians or churchmen charged with compiling the history of the churches under Nazi rule. Three dynamics contributed to the divided response to the work of a practicing Anglican – a confessional divide, a national divide and a methodological divide. Reflecting ongoing confessional fissures, non-Catholic politicians, churchmen, journalists, playwrights and scholars had shown a consistent willingness to enter into or launch public discussions about the Catholic past in the Third Reich, while their Roman Catholic counterparts in the press, ecclesia, intelligensia and academy rarely, if ever, spoke out openly about the Protestant past. Negative reviews in Germany, moreover, reflected a heightened sensitivity to criticism not just from non-Catholics but from the Anglo-Saxon world, from where the majority of the non-German critical accounts of the recent past had come. And finally, Conway’s German critics assailed him for what they regarded as deficient methodologies, and in particular, his unwillingness to show the necessary empathy for his subjects and to employ what can be described as a Quellenpositivismus and refrain from making larger moral and historical judgments not born directly out of the sources he used.

Ruff’s account of the confessional dynamics in the German historical profession of the 1960s set the stage for Robert Ericksen’s paper, “Church Historians, “Profane” Historians, and our Odyssey Since Wilhelm Niemöller.” Wilhelm Niemöller was the younger brother to Martin Niemöller, an important leader of the Confessing Church during the Nazi era and a widely known prisoner of the regime after his arrest in 1937. Martin went on to serve in various church leadership positions after 1945, while Wilhelm emerged as the most important historian of the Protestant Kirchenkampf, or “Church Struggle,” in the first postwar decades. He quite consciously styled himself a “church historian,” separating himself from those historians designated “profane” in the German usage. In the 1960s he wrote, “It almost seems as if one could be satisfied with the rather shortsighted conclusion that church history and ‘profane’ history do not differ from one another.” Ericksen argued that Wilhelm Niemöller, in his effort to bring his faith to the task of writing history, distorted the history of the German Protestant Church under Hitler. He described the history of the Confessing Church, representing approximately 20% of Protestants, as if it were the history of the entire church. He also ignored those within the Confessing Church who supported Adolf Hitler and those who shared the antisemitic prejudices of the regime. Finally, Wilhelm Niemöller ignored the fact that both he and Martin had voted for the Nazi Party, and that he had joined the Party as early as 1923. Ericksen concluded by insisting that historians of churches must work as “profane” or secular historians, if they are to create a more usable and reliable history.

Manfred Gailus’ paper, “Ist die “Aufarbeitung” der NS-Zeit beendet? Anmerkungen zur kirchlichen Erinnerungskultur seit der Wende von 1989/90,” examined how the Protestant church dealt with its own past from the Third Reich. Focusing on the state church of Berlin-Brandenburg-schlesische-Oberlausitz (EKBO), Gailus focused on how Bishop Wolfgang Huber, one of the leaders of the Protestant church, practiced a politics of the past that can be regarded as representative for the Protestant church as a whole. In November 2002, Huber delivered a committed and self-critical sermon for the annual „day of repentance,“ a sermon which he dedicated to the memory of those Christians of Jewish heritage who had suffered and died in the Third Reich. This sermon can be regarded as a sign of Huber’s committed engagement with the past, one comparable with his efforts to compensate church slave laborers from the Second World War. But his subsequent efforts to come to terms with the past began to flag almost immediately thereafter. In 2005, he chose to take up the theme of the „church and the new social movements of the 1960s and 1970s“ – and not the church struggle of the 1930s – as the major theme for the fiftieth anniversary of the „Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte.“ He also stayed out of the longstanding debates about the future of the Martin-Luther-Memorial- Church in Berlin-Mariendorf, a church that had been built during the Third Reich, decorated with sundry Nazi symbols and now enjoyed the protective status as a „historical landmark.“ The church under Huber, Gailus concluded, has certainly come a long way forward in its approach to the Nazi past but still lags behind the standards set not only by professional historians but by the larger public. It remains in urgent need of powerful initiatives to kick-start its reassessment of the past.

The second panel, „Theology, Theological Changes and the Ecumenical Movement“ brought to the table the fruits of recent research. Victoria Barnett’s paper, “Track Two Diplomacy, 1933-1939: International Responses from Catholics, Jews, and Ecumenical Protestants to Events in Nazi Germany,” showed how events that unfolded in Nazi Germany and Europe between 1933 – 1939 sparked a number of significant and ongoing initiatives among international religious leaders. This was particularly true of religious bodies whose scope was international and touched on ecumenical or interfaith issues; such bodies included the Holy See in Rome, ecumenical offices in Geneva and New York, and the conferences of Christians and Jews in the UK and the United States. Such initiatives were also driven by individual Protestants, Catholics, and Jews who were committed to fighting against National Socialism and helping its victims. Many of these individuals, Barnett pointed out, became involved early in refugee-related issues. Other issues of common concern included the ideological and political pressures on both Protestant and Catholic churches in Germany and the desire to prevent another European war. After the war began, many of these same circles had contacts with different German resistance circles, and some of these leaders wrote “think pieces” on the necessary moral foundations for a postwar peace. Although the Catholics and Protestants involved in these activities represented a distinct minority within their respective churches, an examination of their interactions, including their contacts with representatives of Jewish organizations, offers a much fuller picture of the international religious responses to Nazism and show the extent of interreligious communication even before 1939 as an attempt at “track two diplomacy.”

Matthew Hockenos’ paper “‘Blessed are the Peacemakers, for They Shall be called Sons of God’: Martin Niemöller’s Embrace of Pacifism, 1945-55” focused on the theological transformations in the decade from 1945 to 1955 for the former Confessing Church leader and hero, Martin Niemöller. Niemöller, Hockenos showed, jettisoned the Zwei–Reiche–Lehre (Doctrine of Two Kingdoms) and championed a political role for the Church. He abandoned German nationalism and became a leader of the ecumenical movement. He denounced war and the remilitarization of Germany and gradually came to adopt pacifism. Hockenos, however, made clear that Niemöller’s embrace of pacifism did not occur over night, as Niemöller had implied in his own account of his meeting with the German scientist Dr. Otto Hahn. It was a gradual process that one can trace from the time of his liberation to 1955. It appears to have been the result of a number of factors and events. These included including his own reflection on the destructiveness of WWII and the imminent danger that the Cold War posed to Germany, the outbreak of the Korean War, contact with ecumenical-minded church leaders abroad, and the deliberate efforts of pacifists in the United States and in Europe to convince Niemöller that the only position a true Christian could take on war was to be against because it was inimical to the message of Christ. From 1954 on Niemöller made it his primary goal to expand the circle of pacifists person by person through education and example. Just as his pacifist colleagues had slowly reeled him in through conversations and dialogue, he traveled the globe, frequently visiting Communist nations, preaching the way of non-violence and extolling the teachings and example of Mahatma Gandhi.

Wilhelm Damberg’s paper, „Vergangenheitsbewältigung und Theologie nach dem Konzil: J.B. Metz, die politische Theologie und die Würzburger Synode (1971-1975),” drew the attention of conference participants to a major theological paradigm shift in how the Roman Catholic Church in Germany came to terms with its past under National Socialism. Ironically, Damberg noted, this seismic shift has largely remained unknown to historians. It took place during the Würzburg Synod of 1971 to 1975, which was charged with implementing the resolutions and decrees of the Second Vatican Council in Germany. The central document for these changes was one bearing the name „Our Hope: A Commitment to Faith in our time.“ It prepared by the renowned German theologian, Johann Baptist Metz, and bore the hallmarks of Metz’s own so-called „Political Theology.“ This document met with the overwhelming approval of the synod. Metz shaped its content around the concept of a collective „examination of conscience,“ which confessed the guilt and failure of „a sinful church“ particularly towards the Jews of the Third Reich. In the formal debates about this document, disagreements broke out about the appropriate way to understand history. Metz defended himself against criticism of his historical judgments by insisting that historical consciousness and actual reconstructions of the past remained two separate things. For the church of the present, it was the former that matter. Metz, Damberg argued, was deconstructing historical narratives that Metz himself saw as being in direct opposition to the epochal theological change of „theology after Auschwitz.“

The third panel on Friday, “Expanding the Borders: Inter and Intra-National, Interdisciplinary and Cross-Cultural Narratives” pointed out new directions for historical research. Thomas Großbölting led off with his paper„‚Kirchenkampf gibt es immer‘: Memory Politics as a Point of Reference for an inner-ecclesiastical Counter-culture.” Großbölting made his focus those moments in the 1960s and 1970s when special groups within the churches and individual Christians referred to the Nazi past. How, he asked, did they draw connections between themselves and the church struggle from the 1930s? He argued that the silence of the 1950s regarding the Nazi past was replaced in the second half of the 1960s by greater openness – and even bluntness. For the new social movements and special interest groups within the churches, in particular, the politics of remembrance became a major point of orientation and mobilization. Organizations as disparate as Una voce, Unum et semper, the confessional movement “No other gospel”, the German branch of Opus Dei and “Christians for socialism” all sought to find new ways of living the personal faith and to radicalize the Christian Gospel. For conservatives, radicalization meant bring the Christian Gospel back to its roots; for left-wingers, it meant rediscovering the communist ideals of the early church. Großbölting, in turn, showed how such groups like Catholic student parishes and Protestant confessional movements referred to the Nazi-past in general and to the Church struggle, in particular, as a way to realize these aims. In spite of the enormous attention they found from the media at the end of the 1960s, the impact of these movements remained limited. The Protestant counter-movement took up the battle cry, “Kirche muss Kirche bleiben” –Church must remain the Church.” But even these stirring words, Großbölting concluded, never found much resonance among the ordinary members of the Protestant and the Catholic Church.

In his paper, “Conflict and Post-Conflict Representations: Autobiographical Writings of German Theologians after 1945,” Björn Krondorfer showed how the questions of gender, and male gender in particular, and of retrospective historical representatives, are central to our analyses of the postwar church. Krondorfer argued that gendered roles and identifications allowed German men in institutions like the church to adjust to a new environment after 1945. His paper critically analyzed the autobiographies of two Protestant German male theologians published after 1945, and in particular, those of Walter Künneth ( Lebensführungen: Der Wahrheit verpflichtet; 1979) and Helmut Thielicke (Zu Gast auf einem schönen Stern; 1984.) Realizing that their autobiographical act of remembering placed them into a morally and politically charged historical context, these two theologians carefully crafted their memoirs, employing apologetic and eluding strategies when accounting for their lives during the 1930s and 1940s. The theme of “German suffering” often looms largely in these memoirs, while Jews are mostly absent; hence, the boundaries between victim and perpetrator are constantly blurred. As “helpless victims,” these men might run the risk of being effeminized, as “acting subjects” they might run the risk of being accused of moral failure. Versions of this mental split, Krondorfer argued, are to be found in almost all post-1945 autobiographies of German male theologians.

Suzanne Brown-Fleming’s paper, “Real-Time Narrative Responses to Nazism: March/ April 1933 in Germany and Rome” focused on the Catholic diplomatic response to the earliest antisemitic measures of the Nazis. On April 1, the Nazis ordered a boycott of Jewish businesses, department stores, lawyers and physicians on April 1, 1933, the first centrally directed action by the National Socialists against Jews after the Seizure of Power. The Civil Service Law of 7 April was the first to contain the so-called “Aryan Paragraph,” stipulating that only those of Aryan descent could be employed in public service. Brown-Fleming Using drew upon the recently-released records of the Vatican nunciature in Munich and Berlin during the tenure of Pope Pius XI. She discussed the exchanges between Pope Pius XI, then-Secretary of State Eugenio Pacelli (Pope Pius XII, 1939-1958), his diplomat in Germany, Cesare Orsenigo, German bishops, and ordinary Catholics and Jews. The elections of March 5, 1933, she argued, revealed a dissonance between the Nazi party, Catholic Center Party voters, and Catholics who hoped to find some way to be both true to their bishops and to Hitler. That dissonance, she concluded, affected the response of the Vatican Secretariat of State and German bishops to the first anti-Jewish laws in April 1933 in ways that still need to be further explored.

The third day of the conference was devoted to a discussion of the future direction of the electronic journal, Contemporary Church History Quarterly. This journal had its origins in the electronic brainchild of John Conway, what he upon his retirement from the University of British Columbia in 1995, modestly called “The Newsletter.” This was an eclectic mixture of book reviews and notices about events dealing with contemporary international and ecumenical church history. A recipient of a Humboldt Research fellowship in 1963-4 and a founding member of the Scholars’ Conference on the German Church and the Holocaust in 1970, Conway was best known for his masterwork from 1968, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches 1933-1945, the first extensive history in English of the National Socialists’ campaign against the German churches and the responses of both the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches. He developed this free monthly electronic newsletter to provide a speedier flow of information on new publications on the history of the churches in the 20th century. Traditional quarterly journals were far too slow in informing readers of new publications and works in progress. In addition, they tended to reach only specialized academic audiences – and not the lay and religious audiences just as keenly interested in the highly charged topic of the churches’ conduct during the Nazi era such as the conduct of Pope Pius XII and the responses of the churches to the Holocaust. Sent out by email to a list-serve of subscribers, Conway’s newsletter went by the name of the Association of Contemporary Church Historians (ACCH), or Arbeitsgemeinschaft kirchlicher Zeitgeschichtler.

In 2009, Conway turned over the helm of the Newsletter to an editorial board, which now includes sixteen theologians and historians based in Germany, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. The editorial board members, almost all of whom were gathered in Vancouver, discussed future directions for the journal, and in particular, how to further transatlantic cooperation. Kyle Jantzen, who almost single-handedly engineered the journal’s technical transformation from a newsletter sent out by an email list-serve to a web-based presence, gave an overview of the journal’s new features and the number of hits recent issues and articles have been receiving. Members also discussed the possibility of developing a continuously updated on-line data base that will compile the new publications in the field – journal articles, articles in edited volumes, edited volumes and monograph – from both sides of the Atlantic.

Last and most significantly, the concluding evening of the conference honored the pioneering work of John Conway, who has distinguished himself not only through his scholarly work but in his tireless efforts to bring together scholars from multiple disciplines and nations. Doris Bergen, Robert Ericksen, Steven Schroeder, Kyle Jantzen, and Gerhard Besier offered formal tributes in the course of Saturday evening.

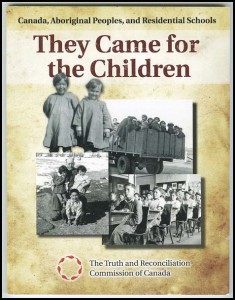

The book explains how the churches in Canada began their missionary work of converting Aboriginals to Christianity and to western cultural practices long before confederation. This foundation proved useful to Canadian government officials who found accord with the church leaders’ intent “to civilize and Christianize” Aboriginal children.

The book explains how the churches in Canada began their missionary work of converting Aboriginals to Christianity and to western cultural practices long before confederation. This foundation proved useful to Canadian government officials who found accord with the church leaders’ intent “to civilize and Christianize” Aboriginal children.