Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 28, Number 1/2 (Spring/Summer 2022)

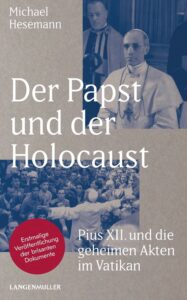

Review of Michael Hesemann, Der Papst und der Holocaust: Pius XII. und die geheimen Akten im Vatikan (Stuttgart: Langenmüller, 2020). 448 pages. ISBN 978-3-7844-3449-0.

By Martin Menke, Rivier University

Michael Hesemann, an independent scholar who has published several works on Pius, on Hitler’s view of religion, and on the Armenian genocide, offers a new contribution to the ongoing “Pius Wars,” the continuing scholarly debate about the degree to which Pope Pius XII opposed national socialist Antisemitism and how much he did to assist persecuted Jews. The spectrum of opinion in this debate reaches from hagiographic apologists such as Michael Feldkamp to vehement critics such as Susan Zuccotti, not to mention Ralf Hochhuth’s early attack on Pius in “The Deputy.” Hesemann makes a case for Pius’s sincere concern for Jewish suffering and his active, pragmatic support for rescue measures. He offers little new insight but amasses a large volume of evidence in the pope’s favor. This work could be a valuable contribution to the discussion, were it not for occasional disparaging comments against those with opposing viewpoints and a failure not only to make his case but engage and disprove the opposing case.

The most important contribution of Hesemann’s work is its exhaustive collection of all evidence and arguments that portray the pope’s record in a positive light. A frequently cited problem was the vague and diplomatic language used in the pope’s statements and writings; Hesemann points to contemporary sources that clearly understood the pope’s intent. Referring to Pius’ first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, which includes a reminder about human fraternity and about the right of the victims of war and racism to human compassion, Hesemann points to the New York Times, which reported that the pope “condemned dictators, those who break international agreements, and racism.” Furthermore, the Times reported that while such a condemnation had been expected, “only few observers had expected the condemnation to be so clear and unequivocal” (104). Hesemann’s evidence suggests that Pius was not only not silent but that readers understood his guarded speech as he intended.

The most important contribution of Hesemann’s work is its exhaustive collection of all evidence and arguments that portray the pope’s record in a positive light. A frequently cited problem was the vague and diplomatic language used in the pope’s statements and writings; Hesemann points to contemporary sources that clearly understood the pope’s intent. Referring to Pius’ first encyclical, Summi Pontificatus, which includes a reminder about human fraternity and about the right of the victims of war and racism to human compassion, Hesemann points to the New York Times, which reported that the pope “condemned dictators, those who break international agreements, and racism.” Furthermore, the Times reported that while such a condemnation had been expected, “only few observers had expected the condemnation to be so clear and unequivocal” (104). Hesemann’s evidence suggests that Pius was not only not silent but that readers understood his guarded speech as he intended.

Beyond the question of papal ambiguity and silence, Hesemann devotes much of the work to proving that the pope was active and vocal about the holocaust. Addressing the pope’s supposed inactivity during the holocaust, Hesemann lists many instances in which the pope quietly directed that financial resources, albeit limited, be provided to help those persecuted by the National Socialists. At the same time, Hesemann shows that this aid extended beyond Catholics whom the national socialist regime considered Jewish. The examples he provides show that his assistance was reactive rather than systematic. In light of the immense need, the Vatican necessarily limited its expenditures in aid to those persecuted. Hesemann also argues that reliable information about persecutions, especially about mass murder, was challenging to obtain. According to him, Pius learned of the true extent of the genocide only after the war. (212) On the same page, however, Hesemann argues that the pope received eyewitness accounts proving the systematic nature of the murders in the East “already a few weeks before the Wannsee Conference.” (212). Thus, in January 1942, the pope knew the National Socialists were murdering according to a concrete plan. How then, as Hesemann describes a few pages later, in September 1942, could Monsignor Montini (later Pope Paul VI) have honestly told American envoy Myron Taylor that the Holy See did not possess information “confirming this grave information?” (216). To argue that the pope knew about violence, terror, and massacres, but not about the extent of the genocide seems farfetched.

Hesemann devotes an entire chapter to “the ‘wise silence’ of the pope.” (220). Pius’ silence was the result of bitter experience, claims Hesemann. Pius himself claimed that any public statements condemning Antisemitism and the holocaust were counterproductive. To each one, the national socialist regime responded with increased persecution. (208) The most robust case for reticence was the Dutch experience under occupation. Beginning in 1941, the Dutch had publicly protested against German antisemitic measures. Each time, the Germans had responded with enormous levies and additional arrests. When deportations began in 1942, the Catholic Archbishop of Utrecht ordered his protest read in all churches. (222) Within days, all Dutch Catholics whom the occupation forces considered Jewish were deported, among them Carmelite religious Edith Stein. According to the pope’s housekeeper, upon hearing the news, the pope immediately burned the draft of the public protest he had intended to make in support of the Bishop of Utrecht. German responses to Radio Vaticane’s regular reports about atrocities against Catholics led to arrests of priests, executions, and more. (231) In response to the pope’s Christmas broadcast of 1942, in which he condemned the suffering of innocents, including those persecuted based on race, the German Foreign Office threatened the pope with reprisals in Germany, should such “interference” occur again. (241). Hesemann makes a strong case that a broad, explicit public condemnation of the genocide would have wrought much suffering. However, one must ask if safeguarding the moral integrity of the Catholic Church’s leader might not have been worth the price in the scope of the crimes committed, preserving the moral integrity of the leader of the Catholic Church might not have been worth the price?

The book’s argument falters when Hesemann presents an image of Pope Pius XII as a friend of Jews, perhaps “the church leader best-disposed to Jews during his lifetime.” (61). For example, the author points to a Jewish childhood friend with whom Pius was close and whose emigration to Palestine he facilitated in 1938. More generally, Hesemann’s case for Pius’ pro-Jewish attitudes and activities during his time as nuncio in Germany relies on the testimony of Pinchas Lapide and Nahum Sokolow. Problematic are claims that Pius XII condemned the Reich pogrom of 1938 because he “must have approved and possibly even dictated himself” the Osservatore Romano’s critical response to this violent persecution. To claim that there was “no leading Catholic clergyman other than Eugenio Pacelli who opposed Hitler and National Socialism as early and as uncompromisingly” is an audacious claim. (92) Sometimes, even among the best historians, the desire for a particular “past” colors one’s work. There is no doubt that Hesemann gathered much evidence to support his case. In the cases mentioned above, the evidence presented by Hesemann broadly supports his argument. Still, a more solid foundation of evidence is needed to support some of the claims made convincingly.

The publisher’s jacket cover promises “the first publication in German of these explosive [brisant] documents.” Anyone expecting full-length explosive and previously unpublished documents will, however, be disappointed. In only two cases does Hesemann claim to offer documentary evidence he newly discovered. For example, he found a message of January 9, 1939, in which Pius, still Cardinal Secretary of State Pacelli, appealed to all leading archbishops to create structures to welcome Catholic refugees whom the Third Reich considered Jews. Pius XII claimed that about 200,000 individuals the regime considered Jewish fell into this category. Hesemann points out that this number exceeded the number of Catholics persecuted as Jews, which meant that Pius sought to create opportunities for practicing Jews. (79-80, 148)

Hesemann’s summary of post-war Jewish expressions of gratitude is exhaustive but not novel. Several significant document editions appear in the citations. However, his archival research is limited to records in the Vatican Secret Archives, specifically those of the nunciatures in Munich and Berlin and the apostolic delegation in Turkey. The documents Hesemann found in the Vatican Secret Archives generally are not new. Of the relevant scholarly literature used by Hesemann, some appeared recently, but a good number of the works are outdated. Even fifty years ago, Father Ludwig Volk, SJ, who had seen the Secret Archives, warned that this collection contained no smoking guns.

In part because Hesemann relies on questionable scholarship, his work lacks judiciousness. For example, he describes Hochhuth’s play as the result of a KGB plot (18) without mentioning that this claim stems from a largely unverifiable work by former Romanian secret police officer Ion Pacepa. Hochhuth did not need the KGB’s help writing “The Deputy.” Even were this assertion correct, it is not surprising that the Soviet bloc sought to embarrass the Vatican, nor does such a connection change the content or impact of the play. Hesemann dismisses rather than engages the work of Michael Phayer, Susan Zuccotti, and others. Accusing David Kertzer of inventing the claim that Pius XI did not want to publish an encyclical that would offend Hitler is a scholarly accusation that deserved a much more detailed explanation. In general, Hesemann undermines his work by this combination of disparaging scholars with contradictory opinions and failing to disprove their claims.

Beyond the corpus, the book includes a preface by Father Peter Gumpel, Ph.D., SJ, deeply involved in the canonization process of Pius XII. In the acknowledgments, Hesemann thanks Pope Benedict XVI for his encouragement and leading German curial officials for their help as he wrote the manuscript. While the preface and acknowledgments do not predetermine the book’s conclusions, they suggest that Hesemann would have felt the need to be all the more critical of his sources and their arguments to avoid the appearance of prejudice.

Reading the work without context, one seems to see a convincing case for an actively engaged pope, one who opposed National Socialism at every turn but whom experience had taught to be diplomatic and to act “under the radar,” without openly condemning his powerful enemies. Such a reality would have been an almost ideal papacy. This wishful thinking is not exclusive to Hesemann. It seems that, at least for now, the “Pius Wars” will continue to obstruct objective scholarship.

Michael Hesemann’s recent book The Pope and the Holocaust: Pius XII and the Vatican Archives.

As students of history, we cannot judge the Catholic Church according to the actions of one man. Rather we must rise above present debates and controversies to come to a clearer understanding of the political forces and ideologies at play among the various groups at that time. Pius XII was a man born into a transitioning world. He tried his best to steer the catholic ship to peaceful waters. In our present moment we might see matters differently. The great temptation is to judge the past as not living up to our present-day expectations and dismiss it altogether.

I believe that Pius XII will eventually be made a saint—not because of his failure when it came to speaking out for the Jewish people before the late summer of 1941, but rather because of what he accomplished after that summer, namely his trying to save Jews whether baptized or not. Other factors would include his proclaiming the feminine principle, through the dogma Munificentissimus Deus—on the Assumption of the Virgin Mary into heaven—which is the unconscious destiny of Catholicism (Jung). In this Mary’s body is seen as included in the metaphysical realm (inclusive of the feminine within the natural order). Added to this was Pius’ opening of the doors for modern-day biblical scholarship.

I begin by reviewing a few of Hesemann’s recent findings from the Vatican Archives. Examples in support for what he presented as well as his interpretations are:

1) His resolution of a query of concern raised by the catholic priest and scholar John Pawlikowski over the Riegner Report delivered to the World Jewish Congress on March 18, 1942, forwarded the very next day to the pope.

2) His coverage of the Dutch episode, further bolstering support for Pius’ humbled and tortured silence, as well as his reasonable response to the events at hand—rather than grandstanding to the media to look good on the world stage.

3) His discovery of a papal letter written by Cardinal Pacelli to the bishops of the world. This happened two months after Kristallnacht on January 9, 1939. The list of those whom he wrote is impressive and comprehensive. Therein he asked the bishops in each diocese to form committees to help the over 200,000 non-Aryan Catholics who needed help to get out of Germany. He also asked for help in finding them lodging, social services, and places of worship. When Hesemann “discovered this document in the Vatican Archives in 2010, the Pave the Way Foundation subsequently published it for the first time, making headlines around the world. Even in Israel, the Jerusalem Post and Haaretz, the largest English-language and the largest Hebrew newspaper in the country, reported on it. After all [states Hesemann], the document proves without a doubt that Cardinal Secretary Pacelli, with the greatest urgency, made every effort to enable 200,000 people who were considered Jews by the Third Reich to emigrate and thereby to save them from further persecution (and ultimately from the Holocaust, even though in 1939 no one could have imagined that yet). This is great news. Unfortunately, very few of these baptized Jews were helped. By that time the world had turned its back. We see this later in 1939 when Hitler allowed nine hundred Jews to leave Germany on the SM St. Louis. Only a few were allowed to disembark upon their arrival at Cuba. Eventually they were forced to return to Europe with most perishing in camps—a few survived the war. What Pacelli’s letter translates into, as I show below, is that by then it was getting harder and harder to help the Jews. If they were to be helped at all, then they had to go through their own Jewish agencies, while baptized Jews would be forced to go through the Saint Raphael Society, which facilitated emigration for 1,850 former Jews and half-Jews, as well as 261 Jews married to Catholics.” At that time sizable donations came from the Vatican. The Saint Raphael Society was “closed by the Gestapo on June 25, 1941, [with] the bishops’ relief agencies in Berlin and Vienna” picking up the slack. Although it was dangerous to help non-baptized Jews, the Saint Raphael Society did help a few “[Father Centioni explaining] …all this had to happen in the strictest secrecy, the relief programs by the Church could not be known…. This network gave Jewish families passports and money, to make it possible to flee.”

4) Regarding Pius’ supposed silence over the events which transpired in Poland. In 1939 we learn from Hesemann that many Poles did not know about the papal protest, revealed in Hesemann’s book and suppressed by the Polish bishops themselves—believing this would only lead to greater persecutions. Augmenting his position Hesemann chronicles the German reaction to Cardinal Hlond who stated “that the Polish people must rally around [their] priests and teachers. Subsequently countless priests and teachers were either arrested, shot, tortured to death…or else sent off to the Far East.”

Again, concerning Pius’ misunderstood silence, we learn that when matters came to the priests at Dachau one priest inmate, Jean Bernard from Luxembourg, recounted that “detained priests trembled every time news reached us of some protest by a religious authority, but particularly from the Vatican”—having the effect that their guards would unleash their fury against them. It is these realities that Kertzer fails to acknowledge.

5) Amazingly, on page 59 Hesemann informs us that as the persecutions increased, the Jewish community approached the director of Caritas to prompt the famous and outspoken Bishop Clemens von Galen to speak out on their behalf. The bishop responded that he would do so “provided the Jews promised him in writing that they would not hold him accountable if the Nazis were to order retaliatory measures as a result of [his] protest.” They thought about it and declined.

6) One extraordinary accounting—until recently only mentioned as a possible myth, and then discounted altogether by John Morley in his book Vatican Diplomacy and the Jews During the Holocaust 1939-1943—reports that Pius sent his nuncio Cesar Orsenigo to converse with Hitler directly about the Jews. Hitler became enraged and rattled his knuckles on the table, then paced the floor, while picking up a glass and smashing it on the floor. The meeting was over. Through Hesemann’s archival finding we now know that this incident really happened.

7) A provocative concern around Pius XII has to do with tyrannicide—the killing of a tyrant and its ethical justification. Throughout the Church’s history tyrannicide was inadmissible. Later Thomas Aquinas justified it “to preserve good order.” If the ruler broke faith with the common good and committed sedition then the “appropriate action might be taken by private citizens and public authorities.” The historian Beth Griech-Polelle advances that “Catholic theology in Germany by the late 1800s was dominated by a neo-scholastic movement which . . . condemned the idea of civil disobedience, “or at the very extreme, tyrannicide.” “These teachings [were] reinforced by the Encyclical Syllabus of Errors of 1864, [which again condemned it], even against governments that practiced injustice and exemplified tyranny.” In his book Hesemann dedicates a chapter to tyrannicide while outlining how Pius was actively involved in supporting attempts on Hitler’s life. This is all new in that what was seen before as fragmented evidence, now comes to us through recent documentation from the Archives—giving us a clearer picture as to Pius’ involvement. Absolute secrecy was required on the part of the Church or else it would be destroyed.

Major flaws in Hesemann’s work include:

1) A major flaw in Hesemann’s research is his problematic linking what lay within the Vatican’s archives to a series of flawed, and taken-for-granted, historical misconceptions concerning not only the role of the Vatican leading up to the Shoah, but also the role played by Cardinal Faulhaber—a central spokesperson for the Catholic Church in Germany at that time. I cover this in greater detail in my next book beginning with Faulhaber’s Advent sermons of 1933 until the end of the war. Hesemann’s dubious linking of his documentation to false claims begins with his comment regarding Article 29 of the concordat, whereby he points out that at this time the Church stood up for the Jewish people, which was not the case in terms of the racial persecutions. What Article 29 did accomplish, was to make it possible for baptized Jews to attend mass and be members of catholic societies. This became redundant once the persecutions began with most baptized Jews staying at home—having to wear the yellow star. Article 29 had nothing to do with, standing against Nazi racial ideology.

Rather, what actually happened with respect to the Concordat, concerning the Jewish people tells another story, which happened on April 4, 1933, when Cardinal Pacelli wrote Orsenigo in Berlin directing him to explore the possibility of a diplomatic intervention against “anti-Semitic excesses” in Germany. Orsenigo answered that any intervention by the Holy See would be impossible in that anti-Semitism was now part of the official policy of the German government. “The Church could not protest German laws which would be interpreted ‘as interference in internal politics.’” Also, once the Concordat was signed, the Holy See would be barred from interceding publicly on behalf of the Jews. By September when the Concordat was finally ratified, “Pacelli handed the German chargé d’affaires, Hanns Kerrl, a ‘Promemoria’ of the Holy See [stating] that ‘the Holy See permits itself a word in favor of Catholics who have come to the Church from Judaism.’” Jews as such were not the topic of his concern. Hesemann is not only mistaken in his presentation of the facts but leads his readers away from the actual events and what really transpired.

How did the government respond to this pro memoria? Certainly, it could not suspend its racial beliefs by making a special case for the Christian churches. How could racial beliefs stay intact while accommodating Christianity—as well as the Aryan families who had welcomed baptized Jews into their families? In response it would be blood, and not baptism that became the overriding factor. The Aryan blood of one partner would be seen as offering the necessary protection to their partners Jewish blood—a blanket of protection. Special cases would be dealt with according to a comprehensive chart known as the Nuremberg racial laws, which came two years after Pius’ pro memoria. Children were also be protected through their parent’s government-protected Mischling status. Difficult cases would be handled over to tribunals and if in question remained then these were to be directly referred to Fuhrer.

2) Another of Hesemann’s oversights has to do with Cardinal Faulhaber’s Advent sermons. In Advent of 1933 the Church was under attack. Cardinal Faulhaber had his flock to protect. In his Advent sermons he extends the dogma of Mary’s sinless state—bequeathed to Mary alone throughout the Church’s entire history—as now possibly applying in a similar fashion (as it did for Mary) to biblical Jews. Could not God have given similar graces as those imparted to Mary “to the whole bridal equipment of the people of Israel…500 or even 5000 years earlier, though they first welled up at the foot of the cross. … The whole bridal equipment of the people of Israel, her election, her promises, her law and the other sacred books, her liturgy and the marvels of her history, all of this was a loan from the Cross of Christ, a loan, I say, using the term by way of a similitude.” From this one paragraph, Nazis, as well as believing Catholics, would be left with the impression that Mary’s blood was somehow “filtered,” for lack of a better word, through her immaculate state—these are the author’s words and not those of Cardinal Faulhaber. Purified in this manner, Mary’s blood could be perceived as having nothing in common with the blood of Jews living in Nazi Germany. With this one statement Cardinal Faulhaber was able to rescue the Jewish scriptures for Christianity, while at the same time —and with that same statement—to disassociate the Jewish roots of the catholic faith from having any perceived racial connection with Jews living in Nazi Germany. Jews would be left to fend for themselves—a similar Marian disassociation toward the Jewish people as used by Karl Adam, Michael Schmaus and others. Faulhaber, to justify his intentional misrepresentation of Mary’s image—as I will show—recounts the lie of “Judith of Bethulia” who lied to save her people—found in the Book of Judith. In 1933 the cardinal asks his listeners whether, in a similar set of circumstances, what Christian would act differently than Judith if their community was under attack? So too it was with Cardinal Faulhaber and his intentional misrepresentation of Mary’s image in his Advent sermons.

It is all well and good that Hesemann places his research within the context of what has already been laid out by others in the Vatican document “We Remember: a Reflection on the Shoah,” but by doing so he is not on solid ground. If one looks closer at the contextualization of his newfound facts taken from the Vatican Archives, through his accounting of Cardinal Faulhaber–page 28-37 in The Pope and the Holocaust: Pius XII and the Vatican Archives—then one sees an inversion of the facts as to what actually happened. Yes, it is true, as Hesemann recounts that Cardinal Faulhaber was a courageous man, and that on several occasions he spoke out for the Jews—outlined in my previous book and covered again below—but it is simply not the case that he stood up for the Jewish people in his Advent sermons.

Does Hesemann not know that Cardinal Faulhaber’s Advent sermons were presented shortly after the Vatican had taken the lead in signing off on the concordat in 1933—agreeing not to interfere in politics, which included the Jewish question. If Hesemann has misconstrued the meaning and intent behind Cardinal Faulhaber’s Advent sermons, as have those within the Vatican—based on what is problematically reported in the document “We Remember: a Reflection of the Shoah” (1998)—then de facto he also exonerates those within the Vatican who signed off in 1933 on the Jewish question. Hesemann’s framing of events covers up more than it reveals.

Returning to Cardinal Faulhaber and the papal document “We Remember.” Before its release the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith delayed it for several years. According to the late Cardinal Cassidy this came about because of passages added about Cardinal Faulhaber. Given this scenario, as again laid out in my recent book The De-Judaization of the Image of Jesus of Nazareth (the Virgin Mary) at the Time of the Holocaust: Ensoulment and the Human Ovum and after much thought, I now realize that “We Remember” was the first attempt by the Vatican to suggest how catholic scholarship might wish to proceed. By adding the comments on Cardinal Faulhaber and his Advent sermons—the reasons for the document’s delay—those within the Vatican were intentionally and rightfully drawing attention to the central catholic narrative expressed at that time in Nazi Germany. They were insisting that in examining the plight of the Jews “as well as” the persecution of faithful German Catholics, they might best begin by examining the writings and actions of Cardinal Faulhaber. In other words, if one is to examine the role of the Catholic Church in Nazi Germany, then one must begin with Cardinal Faulhaber and his Advent sermons. Unless these additions were accepted, “We Remember” would not be released. It was finally released years after in March 1998. In hindsight I now agree that this was the proper way for the Vatican to proceed.

What “We Remember” overlooked, however, was that with the signing of the Concordat in tandem with Cardinal Faulhaber’s Advent sermons, which came shortly after, the path was set for German Catholics for the remainder of the war. Before the merging of these two positions—the Concordat and Cardinal Faulhaber’s Advent sermons—came Cardinal Pacelli’s earlier response to the Jewish question, outside the terms of the Concordat, of putting in a good word for baptized Jews—not noted by Hesemann. It is here that Hesemann muddies the waters by conflating Article 29 (above) of the concordat as standing up for the Jewish people; when it was precisely through its signing, by which the Vatican disengaged from the Jewish question—later supported by Cardinal Faulhaber’s Advent sermons. In support of this claim is Faulhaber’s later meeting with the chancellor at the Berchtesgaden on November 4, 1936, at which time he reiterated the Church’s position. “So,” said Hitler, “will the Church carry on with its fight against the racial laws?” The cardinal responded, “Even before, under the monarchy, there were laws to which the Church had to object (divorce 1875, abortion in first trimester, etc.).” Here Faulhaber was telling the Chancellor that the Church had always peacefully coexisted with regimes even when it did not see eye to eye on every matter. By placing the race laws on the same footing as abortion and divorce—by clearly stating, as it always had, that the Church could not agree to them but could live with them—Faulhaber was able to minimized his objection causing the Fuehrer to ease up on a number of cases against the Church. Without including the above in his study on Pius XII, I believe Hesemann will remain stymied in his ability to properly contextualize his documentation coming from the Vatican Archives. One must remember that at this time the Church in Germany was trapped.

Hesemann’s failure to address how the Vatican and the German bishops accommodated the Nazis, when it came to the Jewish question beginning in 1933—out of the necessity to survive—secured through Cardinal Faulhaber’s problematic use of Marian dogma, is of monumental importance for today’s scholarship. If not addressed, it is my belief that something important will be lost to history. By painting Pius XII as someone who advocated on behalf of the Jewish people while conveniently leaving out the above narrative—which is what this book is all about—Hesemann downplays the reality that Pius could have had a pivotal moment of awakening to the horrors at hand—at which time he changed course to help nonbaptized Jews as well as those who were baptized. If there was a pivotal moment then one must ask, when was it?

3) The late John Conway once observed that from late in 1941 onwards those within the Vatican became aware of the scale of the persecutions inflicted on the Jewish people and began in earnest to instruct their officials to offer help against the atrocities taking place. Hesemann’s documentation supports Conway’s hypothesis as does Morley in his book Vatican Diplomacy and the Jews During the Holocaust 1939-1943 written in 1980. How did this change in Vatican policy come about?

One episode reported by Hesemann shows that two days before the papal audience with the refugee Wisla, Pius met with the cleric Don Pirro Scavizzi who handed him a report on November 24, 1941, on the genocides wherein before his eyes Pius,

wept like a child…Deeply shaken, [he] listened to [Scavizzi], asked him for a complete report, and begged him in his future travels to ascertain as many details as possible about the extent of the persecution and massacres.”

This archival evidence, as well as other evidence shows that from late in 1941 onwards Pius began in earnest to instruct his officials to offer help against the atrocities taking place. But what about before that time? Did Pacelli’s concern and commitment to non-baptized Jews happen earlier? Documentation shows that on January 9, 1939, two months after Kristallnacht, he wrote a letter to the bishops of the world. This happened shortly before his pontificate, while Pius XI lay on his deathbed. In his letter he pleaded with the bishops to aid baptized non-Aryans, thereby pushing the timeline for his concern and care for 200,000 baptized non-Aryans—seen as Jews by the regime—back even further. Did this distil into the fact that he only spoke out for baptized Jews? For the time being, yes; but in the long run, no. Hesemann’s research shows that on August 1, 1941, seated in front of the microphones of Vatican Radio [Pius XII] mentioned the,

great scandal…taking place [which]…is the treatment suffered by the Jews…In Germany, the Jews are killed, brutalized, tortured because they are victims bereft of defense. How can a Christian accept such deeds? These men are the sons of those who 2000 years ago gave Christianity to the world.”

The above supports Conway’s timeline outlining Pius’ concern for non-baptized Jews beginning late summer—August 1, 1941—thus pushing the timeline back from Don Pirro Scavizzi’s meeting on November 24, 1941?

In conclusion, we see that from January 9, 1939, and beyond Pius showed a deep and abiding concern—as well as financial support—for baptized Jews. Also, beginning August 1, 1941, he publicly stated his concern for all Jews. But certainly, there is more to this than meets the eye. I pick up on this below.

The precise date for Pius’s turnaround concerning non-baptized Jews, based on the horrors of what was happening, is probably lost to history, but for certain his meeting with Don Pirro Scavizzi and his broadcast are significant markers. No matter how noble his efforts, however, they often failed due to political realities dictating his lack of freedom to act in the way he would have preferred. With this stated, it is of great importance to affirm Hesemann in his accounting of the documents he has brought forward from the Vatican Archives, while at the same time, question his interpretation of other facts—in particular the role played by Cardinal Faulhaber and his Advent sermons.

For the remainder of this study, I support Conway’s, Morley’s, and Hesemann’s accounting that after late-summer 1941 onwards those within the Vatican became aware of the scale of the persecutions inflicted on the Jewish people and began in earnest to instruct their officials to offer help. I leave it to others to comment on what transpired after late summer 1941 in the wider Europe, while focusing on that part of Germany under the terms of the Concordat of 1933. I do this with specific reference to both baptized and non-baptized Jews.

In the following pages my chief concern will be to examine the underlying edifice of “how” the Catholic Church dissociated from the Jewish question as laid out by Cardinal Faulhaber in his Advent sermons—presently lost to history. By Hesemann’s failure to realize that the present-day base narrative on which those within the Vatican, including himself, have come to rest their narrative, is severely flawed. To rest his archival findings on historical misrepresentations is unacceptable. By doing this he forswears any possibility of exploring the authentic catholic narrative at play at that time. Rectifying this mistake, I believe, would not only correct the historical record, but lead to a much needed and more balanced interpretation of Pius XII—inclusive of his championing the feminine principle through the dogma of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven, promulgated in 1950 as well as his opening the doors on biblical studies. Such a study could also help better situate our understanding of Marian dogma toward future endeavors—to better serve the human condition (J.B. Metz). Archival research is one reality but giving it proper grounding according to the catholic narrative as presented throughout the Church’s history, is equally important. By following the Church’s response to the Jewish people in Nazi Germany and how Marian imagery came into play at that time, is my small contribution to the field of Holocaust studies.

4) Lastly is Hesemann’s failure to articulate and situate for the reader, the two tenuous foundations on which Pacelli was forced to operate, namely the blood libel, and the sin of deicide attributed to the Jewish people throughout history. In this regard Hesemann fails to contextualize Pacelli’s three page forward to Mgr. Pio Ceni’s book in 1933, which supported one blood libel accusation involving Cardinal Del Val—a senior Vatican official—whose ancestor was purportedly murdered by Jews, as well as Pacelli’s later comment at the 34th International Eucharistic Congress held May 25-30, 1938, in Budapest, Hungary, at the height of the government’s new anti-Semitic legislation. At that time he repeated before thousands, the sin of deicide against the Jewish people was still on the books of Christianity. How can one respond to this? With these two underlying girders of locked-in ideological certitude—the blood libel and the sin of deicide—Pacelli would have been forced to acquiesce or face violence against those who attended, while most likely, personally, disagreeing and abhorring the racial anti-Semitism of his day. The Church was trapped. The fact that he used these two tropes before the genocides began points to a pathway which Hesemann fails to consider. At that time there were also powerful prelates who belonged to various factions demanding that he tow the line according to traditional Church teaching. The blood libel, entirely rejected by then—except for a very few cases instituted by past popes—and the age-old accusation of deicide against the Jewish people were realities he had to tacitly accept as political realities of his day. To place these into softer measure Hesemann comments “that ultimately the Nazis in fact murdered almost six million Jews, that they had even planned systematically the destruction of eleven million Jews, was learned by the pope—at the same time as the Allies—only after the war through the Nuremberg trials of war criminals.”