Review of Holy Silence (directed and produced by Steven Pressman, 2020)

Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 3 (September 2021)

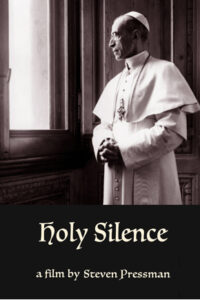

Review of Holy Silence, directed and produced by Steven Pressman (Seventh Art, 2020)

Rebecca Carter-Chand, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum*

* The views expressed are those of the author and do not represent those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Filmmaker Steven Pressman often tells the story of the moment he heard Pope Francis’ announcement in March 2019 that Vatican archival materials related to the pontificate of Pius XII (1939-1958) would soon be made available to researchers for the first time. At the time, Pressman was in the editing stage for his new film, Holy Silence, which offers a fresh take on the longstanding questions about the role of the Vatican during the rise of Nazism and the Holocaust. Pressman has said that although he was initially concerned that the opening of the archives would eclipse his film and render it outdated before it was even released, he soon realized that the timing was fortuitous. With more than 16 million pages spread across several archives in Vatican City and Rome, historians will be filling in missing puzzle pieces and bringing nuance to polarized debates for years to come. COVID-related delays have extended these timelines even further. In this context, Holy Silence offers a balanced and accessible primer to audiences, both newcomers and those well-versed in this history.

The film features several academics familiar to CCHQ readers, including members of the editorial team Kevin Spicer and Suzanne Brown-Fleming. Interviews with Robert Ventresca, Susan Zuccotti, Michael Phayer, Maria Mazzenga, and many others are interspersed with historic footage, and occasional re-enactment to explore the actions of popes Pius XI and XII and some of the innerworkings of the Vatican. Pressman offers a range of voices, including a few outliers like Norbert Hofmann, Secretary of the Holy See’s Commission for Jewish Relations, who views Pius XII in a sympathetic light. We also hear contrasting viewpoints from Sister Maria Pascalizi of the Roman Convent of Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori and Micaela Pavoncello, a local Jew, about the Vatican’s role in sanctioning or encouraging the hiding of Jews in churches.

The film features several academics familiar to CCHQ readers, including members of the editorial team Kevin Spicer and Suzanne Brown-Fleming. Interviews with Robert Ventresca, Susan Zuccotti, Michael Phayer, Maria Mazzenga, and many others are interspersed with historic footage, and occasional re-enactment to explore the actions of popes Pius XI and XII and some of the innerworkings of the Vatican. Pressman offers a range of voices, including a few outliers like Norbert Hofmann, Secretary of the Holy See’s Commission for Jewish Relations, who views Pius XII in a sympathetic light. We also hear contrasting viewpoints from Sister Maria Pascalizi of the Roman Convent of Santa Maria dei Sette Dolori and Micaela Pavoncello, a local Jew, about the Vatican’s role in sanctioning or encouraging the hiding of Jews in churches.

The film is centered on the Vatican, but it employs a distinctly American lens, featuring several American individuals who intersected with this history. The contribution of American Jesuit priest John LaFarge and the so-called “hidden encyclical” drafted in 1938 is explored in detail. Unfortunately, the film does not mention the pre-Vatican II supersessionist and anti-Judaic themes of Humani generis unitas (“The Unity of the Human Race”). Instead, it focuses on LaFarge’s formative experiences ministering in African-American communities, highlighting the transatlantic context in which some people were formulating their critiques of racism in the 1930s and 40s.

Holy Silence concludes with the end of World War II and does not address the postwar entanglements of the Vatican with Nazis fleeing Europe; doing so would require a much longer film than the current 55 minutes. Like any good documentary film, it presents a narrative but asks more questions than it answers. As the debates around the role of the Catholic church and Pope Pius XII in the Holocaust receive new breath due to the opening of the archives, this film provides an entry point for productive discussion about the role of religious leaders, the relationship between large religious institutions and governments, and local dynamics between religious majorities and minorities.

Holy Silence is available to stream through PBS and Amazon Prime. Recordings of multiple panel discussions about the film co-sponsored by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum are available on YouTube.