Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 3 (September 2021)

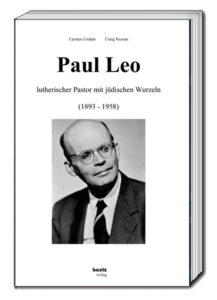

Review of Carsten Linden and Craig Nessan, Paul Leo. Lutherischer Pastor mit jüdischen Wurzeln (1893–1958) (Nordhausen: Traugott Bautz, 2019). 86 pages. ISBN 978-3-95948-453-4.

By Dirk Schuster, University of Vienna / Danube University Krems

Historian Carsten Linden and Craig Nessan, Professor of Contextual Theology at Wartburg Theological Seminary in Dubuque, Iowa, present the life and work of the Lutheran Evangelical pastor and theologian Paul Leo (1893–1958) in 86 pages. Linden wrote the first part, Nessan the second. Unfortunately, the two parts are not well coordinated, so that there are repetitions in places. The relevance of examining the life of Paul Leo and paying tribute to him with this booklet lies in his family of origin. One of his ancestors was Moses Mendelsohn. Still, like his father, Paul Leo was a baptized Christian. At this point, a great nuisance begins: Carsten Linden writes about Paul Leo, who was baptized in infancy: “The extent to which he was Jewish, however, seems to be a little in the eye of the beholder” (p. 7). Linden is right in referring to interpretations of Jewish theology stating that the descendants of a Jewish mother are Jews. The annoyance, however, is that the author assumes Leo could possibly have a Jewish identity, just as the National Socialists did. For them, the Protestant pastor was a Jew because of his ancestors. Why Linden does not simply accept Leo’s religious self-image as a Protestant Christian at this point, instead of relying on external attributions, remains unclear.

Based on extensive archival source material, Linden describes Paul Leo’s early professional career. When the National Socialists came to power, Leo faced increasing difficulties due to his Jewish ancestors. Why Linden then adopts the racial biological interpretations of the National Socialists in this regard and describes Paul Leo as the “Jewish pastor of the regional church” (p. 19) is disturbing, however. Unfortunately, Linden also makes significant mistakes in terms of content: The Confessing Church did not form due to alleged state and National Socialist (where should a dividing line be drawn here?) interventions in church affairs (p. 18). This apologetic church historiography of the 1950s has been refuted many times in recent years, which should be taken into account when dealing with such a topic.

Based on extensive archival source material, Linden describes Paul Leo’s early professional career. When the National Socialists came to power, Leo faced increasing difficulties due to his Jewish ancestors. Why Linden then adopts the racial biological interpretations of the National Socialists in this regard and describes Paul Leo as the “Jewish pastor of the regional church” (p. 19) is disturbing, however. Unfortunately, Linden also makes significant mistakes in terms of content: The Confessing Church did not form due to alleged state and National Socialist (where should a dividing line be drawn here?) interventions in church affairs (p. 18). This apologetic church historiography of the 1950s has been refuted many times in recent years, which should be taken into account when dealing with such a topic.

Since Paul Leo was mainly responsible for pastoral care in state institutions, he successively lost all of his responsibilities, as a result of which the church council assigned him the Osnabrück district of Haste for pastoral care. But even there, Paul Leo was increasingly hindered in his work because he was considered a Jew in the National Socialist understanding. The church council therefore decided to suggest ‘temporary retirement’ to Leo in mid-1938. On November 9, 1938, Paul Leo shared the same fate as thousands of Jews throughout the ‘Third Reich’: the SS arrested him and deported him to the Buchenwald concentration camp. Since Paul Leo received a visa for the Netherlands, he was released from the concentration camp at the end of 1938. However, he never spoke about his experiences there. In the Netherlands, he also had to live separated from his daughter (the mother had died during childbirth), which, in addition to the loss of his homeland, was certainly another inhuman burden. From the Netherlands, Leo then came to the USA in 1939, where he held various positions as pastor and theologian until his sudden death in 1958. Craig Nessan describes this second phase of life in Leo’s new home in America. It becomes clear how difficult life could be for exiles in the first few years.

The brief account of the life and work of Paul Leo is a classic descriptive biographical treatise. It conveys very well the depressing circumstances under which people had to live who did not belong to the ideal of the National Socialist ‘Volksgemeinschaft.’ And as a pastor, Leo received no significant protection from the regional church. From the point of view of the reviewer, the description of Leo’s first years in the USA is particularly impressive. Despite his successful escape from Nazi Germany, which ensured Leo’s and his daughter’s survival, the first few years were a struggle for survival in a completely different society. The Lutheran theologian Paul Leo had to work in his early years as a teacher in a Presbyterian church in Pittsburgh, which ensured his and his family’s financial survival.

Embedding the descriptions within the overall context of the ‘Third Reich’ with the help of current research literature would certainly have done the book some good, even more so a final editing. The many grammatical errors are unworthy of an appreciation of Paul Leo’s life.