Review of James Enns. Saving Germany: North American Protestants and Christian Mission to West Germany, 1945-1974

Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 25, Number 3 (September 2019)

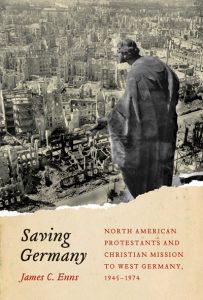

Review of James Enns. Saving Germany: North American Protestants and Christian Mission to West Germany, 1945-1974 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017). 328 Pp. ISBN: 9780773549135.

By Rebecca Carter-Chand, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum*

From the perspective of North American Protestants in 1945, Germans needed “saving” on a number of fronts: from the lingering effects of Nazism, from the potential allure of communism, from the seemingly inevitable pull of secularism, and perhaps most urgently, from the vast material destruction and deprivation in the wake of Germany’s defeat in World War II. James Enns’ 2017 book, Saving Germany: North American Protestants and Christian Mission to West Germany, 1945-1974, analyzes the role of North American Protestant ecumenical and mission agencies that participated in the reconstruction and spiritual rehabilitation of West Germany in the first three decades after World War II.

Enns examines a range of Protestant missionary responses to postwar Germany and divides his subjects into three broad categories. Ecumenical missionaries were mainline Protestants who worked primarily through the Religious Affairs Section of the American Military Government in Germany, the World Council of Churches (WCC), and the Church World Service. They were invested primarily in relief and reconstruction, particularly helping to rebuild the Evangelische Kirche Deutschland (the main Protestant church) as a pillar of German society. Denominational missionaries represent the second approach, and here Enns focuses on the Baptists and Mennonites. These denominations used pre-existing ties to their German counterparts and sought to build up these communities and their standing in German society. The third category is conservative evangelical missionaries who worked through independent mission organizations of a mid-century fundamentalist bent. The impact of organizations like Youth for Christ and Janz Team Ministries is not well known and the author does a good job integrating these organizations in the larger narrative.

Enns examines a range of Protestant missionary responses to postwar Germany and divides his subjects into three broad categories. Ecumenical missionaries were mainline Protestants who worked primarily through the Religious Affairs Section of the American Military Government in Germany, the World Council of Churches (WCC), and the Church World Service. They were invested primarily in relief and reconstruction, particularly helping to rebuild the Evangelische Kirche Deutschland (the main Protestant church) as a pillar of German society. Denominational missionaries represent the second approach, and here Enns focuses on the Baptists and Mennonites. These denominations used pre-existing ties to their German counterparts and sought to build up these communities and their standing in German society. The third category is conservative evangelical missionaries who worked through independent mission organizations of a mid-century fundamentalist bent. The impact of organizations like Youth for Christ and Janz Team Ministries is not well known and the author does a good job integrating these organizations in the larger narrative.

Although he uses the terms “missionaries” and “missionary activity,” Enns is careful to distinguish the growing rift about the missionary endeavor within American Protestantism. By this period, mainline Protestants who supported the ecumenical movement had moved away from traditional practices of evangelizing and civilizing toward a model of humanitarian self-help (9). At the other end of the spectrum, conservative evangelical and fundamentalist Protestants remained committed to converting the “unsaved” and promoting an individualized personal faith.

What all these approaches had in common, especially in the first postwar decade, was the goal of promoting democracy. In Enns’ assessment, the Cold War context hovered over all of these various relief and mission endeavors – the motivation to bulwark Germany against communism was much stronger than the desire to help Germans come to terms with their Nazi past. Each group understood the role of Christianity in different ways: ecumenical Protestants were committed to the WCC’s Christian internationalism; Baptists and Mennonites believed their congregational models of church governance best promoted democracy and religious freedom; and conservative evangelicals believed that “inviting Christ into your life” fostered the personal freedoms of democracy (104).

I applaud the author’s integration of Germany’s Freikirchen (independent churches) into the broader narrative of German Protestantism and his ability to juggle several denominations, ecumenical bodies, and ministries in a coherent narrative. The book draws out the powerful transnational influences of individuals like Billy Graham to the growth of a German Evangeliker identity (a neologism that connotes “evangelical” in the North American sense of the term, as opposed to evangelisch, which has always referred to the main Protestant church in Germany).

The analysis is less strong when it relies on the denominational mission agencies’ own articulation of what they were accomplishing in Germany. Regarding the North American Baptists’ efforts to restore Baptist church buildings, he writes that “[t]hey were helping German Baptists claim a legitimate place in the religious life of the communities in which they were resident and thus be agents of spiritual renewal to their own people” (84). The historical actors involved may well have believed the German Baptists to be agents of spiritual renewal, but such a claim should be analyzed in a broader context of German complicity. Ten pages later the author does address the German Baptists’ involvement in Nazi society, but prefaces the discussion with the erroneous claim that German Mennonites were not “compromised by Nazi ideology” (94). A plethora of new research on Mennonites and the Holocaust suggests that Mennonites were indeed compromised by Nazism in many ways.

These criticisms notwithstanding, Saving Germany makes an important contribution to our understanding of transnational religious history in postwar Germany and does so by taking seriously the full diversity of the German religious landscape.

* The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.