Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 21, Number 3 (September 2015)

Review of Patrick J. Houlihan, Catholicism and the Great War: Religion and Everyday Life in Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1922 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015). Xiii + 287 Pp. ISBN: 978-1-107-03514-0.

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

Catholicism and the Great War is a transnational comparative history of everyday Catholicism. In it Patrick J. Houlihan sets out to revise the story of Roman Catholic theology and lived religion during the First World War era in both Germany (where Catholics were a minority) and Austria-Hungary (where they comprised a majority). His subjects include church leaders, military chaplains, front soldiers, women and children at home, and the papacy. And his scope is not only the war but also its immediate aftermath, which allows him to tackle the additional themes of memory and commemoration. This is an ambitious book.

Houlihan’s argument is that conventional interpretations of religion in the First World War, which emphasize the secularizing effect of a shattering war experience as expressed in the voices of cultural modernists, do not capture the experiences of German and Austro-Hungarian Catholics. Rather, he asserts that Catholics adjusted to industrial warfare because their transnational faith and its practices helped them to cope relatively successfully with the upheaval and brutality of war—more successfully than Protestants, whose faith (in the case of Germany) was more closely tied to the defeated state.

Houlihan’s argument is that conventional interpretations of religion in the First World War, which emphasize the secularizing effect of a shattering war experience as expressed in the voices of cultural modernists, do not capture the experiences of German and Austro-Hungarian Catholics. Rather, he asserts that Catholics adjusted to industrial warfare because their transnational faith and its practices helped them to cope relatively successfully with the upheaval and brutality of war—more successfully than Protestants, whose faith (in the case of Germany) was more closely tied to the defeated state.

The book begins with a dense introduction, demonstrating Houlihan’s remarkable historiographical knowledge. Here and throughout the book, the author interacts substantively with a wide array of scholarly literature on religion and war, the First World War, nineteenth- and twentieth-century European Catholicism, military chaplaincy, religion and nationalism, women’s experiences of war, and numerous other topics. It is indeed the strength of his work.

Methodologically, Houlihan eschews quantitative or institutional history, embracing a transnational approach to his subject, which fits well with the internationalism of Roman Catholicism and enables him to avoid the trap of viewing Christian religion only in terms of its instrumental service to national movements and state interests. He also pursues a comparative methodology, highlighting differences between the experiences of German and Austro-Hungarian Catholics, though often distinctions are blurred as examples are drawn freely from both regions. Still, it is worth noting that Houlihan finds Austro-Hungarian Catholicism to have been a vital component in maintaining imperial loyalty and social cohesion, problematizing commonly-held assumptions about the inevitable demise of the Habsburg Empire. Finally, Houlihan also attempts to incorporate elements of the history of everyday life of Central European Catholics, and to blur boundaries between battlefront and homefront, creating what he calls a “family” history of Catholicism in the First World War (16).

All of these streams of interpretation are worked out in a series of chapters on Catholicism before the war, Catholic theology during the First World War, the role of Catholic military chaplains, the experiences of Catholic soldiers, the circumstances of Catholic women and children at home, the influence of the papacy, and memory and mourning among Catholics after 1918.

Leading up to the war, Catholics in Austria-Hungary were overwhelmingly rural, living in traditional local communities of belief. At the same time, however, new imagined communities were emerging in Central Europe, thanks to the various national movements which were often connected to Catholicism. German Catholics, on the other hand, were influenced most powerfully by the legacy of the Kulturkampf, which drove Catholics into a defensive posture, as demonstrated by Catholic political and labour movements. But for most Catholics in Central Europe, the outbreak of war in 1914 was seen mainly as yet another trial to be endured, and as a threat to the coming harvest.

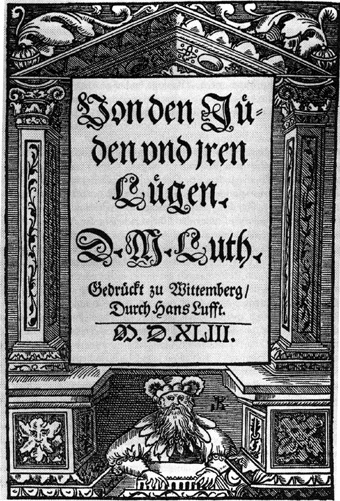

Once the war had begun, German and Austrian bishops were prominent public advocates of just-war theology. For German Catholic leaders, war was a patriotic test of faith. For Austro-Hungarian bishops, it was a call to defend Habsburg dynastic honour and therefore the divine order as they understood it. Military chaplains played a significant role in mediating this theology to ordinary participants, not least by praying for divine blessings on military weapons. As the war dragged on, though, public theology began to emphasize the war as a punishment for aspects of modernity that had drawn Europeans away from God and the Church. And after defeat in 1918, Catholics in former Habsburg lands found themselves reimagining themselves at the dawn of a new day of freedom and opportunity—at least those from minority groups formed into new nation states, such as Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, Poles, and Slovenes. While the “new theologies” of Max Scheler, Romano Guardini, and Karl Adam would bear fruit only later in the 1960s, other “everyday theologies” were also emerging: positively, the rise of a feminine form of Catholicism; negatively, an upsurge of Catholic antisemitism which would later help to pave the way for Hitler and the Holocaust.

Military chaplains—of which there were 1441 in the Prussian Army and 3077 among the Habsburg forces—provided pastoral care among Catholic troops. This they did more effectively in Austria-Hungary than in Germany, according to Houlihan, who uses a case study of Tyrolean Catholics to support this point. Still, all chaplains were overwhelmed by the magnitude of industrial warfare. Houlihan notes that Catholic chaplains enjoyed better reputations than their Protestant counterparts, since they tended to serve closer to the front lines. In one of the best sections in the book, Houlihan explains how chaplains used the three sacraments of communion, confession, and extreme unction to minister to their troops. On the Western Front especially, the cramped quarters of static trench lines made holding a full Mass a rare event. In the end, Houlihan argues that 1916 was a watershed year. Triumphalist “God-with-us” pronouncements gave way increasingly to private doubts about God’s support in war and public reassurances of Christian hope and perseverance in times of suffering.

Among front line soldiers, Houlihan argues that Catholic religion served them better than has often been assumed, in light of the prominent modernist literature of authors like Jaroslav Hašek, Robert Graves or Erich Maria Remarque. Rather, Catholicism was surprisingly resilient in modern conflict, as ordinary soldiers coped with their circumstances by means of a mix of transnational Church institutions, sacramental practices, correspondence with home, superstition (including amulets, talismans, and letters of protection), and popular piety focused on saintly and Marian intercession.

On “the unquiet homefront,” Catholic women and children both suffered and benefitted from the war. Wartime disrupted traditional gender roles. Though public roles for women included war relief, nursing, and industry increased markedly, Houlihan argues that Catholic women in rural Central Europe tended to embrace more conservative, traditional roles. Just as the Virgin Mary was a powerful symbol for frontline soldiers, so too was Mary was a powerful symbol for Catholic women, either in her virginity or her motherhood. Above all, the home front was a nostalgic ideal of piety and peace. Family networks provided comfort—both for soldiers at the front and their wives and family members left at home. And although the First World War opened up new public opportunities for women, Houlihan finds that most rural Catholic women remained focused on local and domestic concerns and traditional religious practices.

Stepping back from the history of everyday religion, Houlihan argues that the Holy See remained fairly impartial during the early years of the war, “nearly bankrupting itself through its devotion to its caritas network of care, especially for POWs, displaced persons, and children” (188). Pope Benedict XV forecast a bloody, brutal war, but argued that the bonds of common humanity and the institutions of the Roman Catholic Church could serve as a force for peace and unity. To that end, his Papal Peace Note of August 1917 called upon the belligerents to embrace peace and civilization. Benedict also oversaw a major revision of Canon Law (1917) designed to strengthen papal power and reinvigorate the Church. Lastly—and here Houlihan returns to his ordinary Catholics—Benedict was important as a symbol. Indeed, many ordinary Catholics wrote to him, hoping he could personally intervene on their behalf or bring peace and reconciliation to a war-torn world.

In his final chapter, Houlihan carries his examination of German and Austro-Hungarian Catholicism into the postwar era, arguing that traditional religious imagery helped Europeans make sense of the war. Themes of collective sacrifice, deference to authority, and universal suffering, grief, and consolation were manifest in monuments and commemorative services, as they had been in the Mass in Time of War. Clergy played an important pastoral role in comforting families of fallen soldiers, just as relics, votive tablets, and other physical objects of memorialization honoured the war dead.

As wide-ranging and as steeped in the secondary literature as Houlihan’s book is, it suffers from a significant lack of primary source evidence. The author acknowledges this in his preface, noting how hard it is to find archival traces of “prayers, fears, and suffering.” As a result, he asserts that his book “is a religious history that gives an impressionistic portrait” (15). It is of course true that this kind of source material is hard to come by, which is why studies of the interior lives of ordinary people are so often local or micro-historical in nature. Repeatedly, Houlihan makes large generalizations based on scant evidence, as in the case of his assertion that Catholics were worried about the impact of the outbreak of war on the coming harvest. This stands to reason, but the statement, “To many Catholics, war was another cyclical plague, redolent of the sinful human condition; it was not cause for celebration” is supported only by one memoir from a Lower Austrian domestic servant and three secondary sources (48). To give another example, a single diary from an Austrian soldier provides the supporting evidence for the conclusion that “soldiers who had to experience the daily horrors of battle often used their faith to cope” (70). Similarly, a single photo of a church service in Weimar Germany along with two references to secondary sources serves to counter the prevailing historiographical view of declining public piety after the First World War (260-261). And no explanation is provided for why a case study of Tyrol would serve to explain the relationship between military chaplains and soldiers throughout Germany and Austria-Hungary (81-82). In sum, while there is little reason to doubt that traditional Catholic religious practices persisted in rural Central Europe during and after the war, Houlihan’s wide-ranging study of this topic makes overly large claims which rest on overly thin evidentiary foundations. Simply put, it is impossible to discern whether or not the phenomena he describes are generally true for early twentieth century Catholicism in Germany and Austria-Hungary, since the his source material is drawn unsystematically from a wide array of regions and positions within Catholicism. He would be far more successful building his case through a series of studies like his useful regional analysis of German military chaplains in occupied France (Houlihan, Patrick J. “Local Catholicism as Transnational War Experience: Everyday Religious Practice in Occupied Northern France, 1914–1918.” Central European History 45, no. 2 (June 2012): 233–67), where his mastery of the secondary literature is combined with a solid and representative collection of evidence.