Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 24, Number 2 (June 2018)

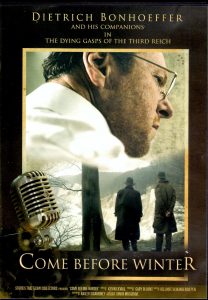

Review of Come Before Winter: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and His Companions in the Dying Gasps of the Third Reich, directed by Kevin Ekvall (Woodbury, MN: Stories That Glow Collectors, 2016).

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

This film aims to tackle two stories in one: the life and thought of German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer during his time in captivity leading up to his execution by the Hitler regime and the “fake news” black propaganda operation of the British journalist Sefton Delmer, assisted by Bonhoeffer family friend Otto John, Berlin-born actress Agness Bernelle, and later James Bond novelist Ian Fleming. It employs a combination of dramatic re-enactment, narration over still and moving images, and explanations from various experts, most notably sociologist Ekkehard Klausa from the Research Centre of Resistance History, ethicist Larry Rasmussen from Union Seminary, pastor John Matthews of the International Bonhoeffer Society, theologian and church official Ferdinand Schlingensiepen of the International Bonhoeffer Society, and Baptist minister and scholar Keith W. Clements, Past General Secretary of the Conference of European Churches, Geneva.

Come Before Winter begins by acknowledging the memoirs and writings of Sefton Delmer, Otto John, Sigismund Payne Best, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer as sources. It then asserts that “one of the tragedies of World War II was the refusal of President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill to acknowledge the existence of a German resistance,” introducing the failed assassination attempt of July 20, 1944. From there viewers are introduced to Sefton Delmer, the British journalist (born and raised in Berlin) who operated several so-called black propaganda operations, broadcasting disinformation into Nazi Germany. The operation covered by the film was the German short-wave broadcast “Atlantic,” which used a powerful transmitter to broadcast jazz, invented personal announcements, and fake news throughout Germany and also to U-boats in the Atlantic during the later war years. Delmer’s goal was to demoralize German troops and to turn the German public against the Nazis. At several points in the film, broadcasts written by Delmer and Fleming (with information from Otto John) and read by Bernelle are re-enacted, in order to depict Delmer’s determined effort to use propaganda to defeat Germany. These scenes also serve as a vehicle for Otto John, a member of the July 20 assassination plot who had escaped to England, to explain the various efforts of the German Resistance to assassinate Adolf Hitler, along with Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s principled participation in the Resistance and his consequent arrest and detention in Tegel prison.

Come Before Winter begins by acknowledging the memoirs and writings of Sefton Delmer, Otto John, Sigismund Payne Best, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer as sources. It then asserts that “one of the tragedies of World War II was the refusal of President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill to acknowledge the existence of a German resistance,” introducing the failed assassination attempt of July 20, 1944. From there viewers are introduced to Sefton Delmer, the British journalist (born and raised in Berlin) who operated several so-called black propaganda operations, broadcasting disinformation into Nazi Germany. The operation covered by the film was the German short-wave broadcast “Atlantic,” which used a powerful transmitter to broadcast jazz, invented personal announcements, and fake news throughout Germany and also to U-boats in the Atlantic during the later war years. Delmer’s goal was to demoralize German troops and to turn the German public against the Nazis. At several points in the film, broadcasts written by Delmer and Fleming (with information from Otto John) and read by Bernelle are re-enacted, in order to depict Delmer’s determined effort to use propaganda to defeat Germany. These scenes also serve as a vehicle for Otto John, a member of the July 20 assassination plot who had escaped to England, to explain the various efforts of the German Resistance to assassinate Adolf Hitler, along with Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s principled participation in the Resistance and his consequent arrest and detention in Tegel prison.

This section of the film contains interesting statements from several of the Bonhoeffer experts about the quest to kill Hitler. Schlingensiepen argues that Bonhoeffer’s extended conversation with German jurist, intelligence officer, and anti-Nazi Helmuth James von Moltke in April 1942 on the island of Rügen revolved around the theologian’s ethical justification for killing Hitler (23:40). When the head of state orders the death of thousands day by day, the only way to stop him is to kill him. Bonhoeffer believed that God left members of the Resistance free to do that, just as God left his son Jesus free to heal the sick on the Sabbath (24:44). Clements notes the difficulty of describing Bonhoeffer as either pacifist or assassin, given the complexity of his situation. Bonhoeffer deeply respected pacifism and knew the costs of war, but was it possible to preserve one’s innocence by doing nothing? (24:10). Rather than dogmatic militarism or pacifism, Bonhoeffer argued people must face their duty to God, and that they determine that duty based on the question of what the consequences will be for other people. This was also the basis for his counsel to other members of the Resistance (25:23). Ethicist Reggie Williams of McCormick Theological Seminary adds that Bonhoeffer acted out of faith, asking what Christ calls us to do in the crisis (25:43), while religion scholar Lori Brandt Hale of Augsburg College notes that Bonhoeffer’s choice to enter the Resistance wasn’t really a choice; he knew that it was necessary and that so few others understood (26:02).

As the dramatized scenes in the film continue, Sefton Delmer and his black propaganda unit continue their work, Otto John laments the destruction of Berlin, and Bonhoeffer sits in Tegel prison. The film details his transfer to the Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse SS headquarters, then on to Buchenwald and the Schönberg schoolhouse in rural Bavaria, until his eventual final imprisonment in Flossenburg concentration camp. Along the way, we’re introduced to an eclectic mix of fellow inmates who encountered Bonhoeffer, including the British intelligence officer Sigismund Payne Best, the German mother Fey von Hassell, the Russian atheist Vassily Korokin, and the German cabaret singer Isa Vermehren. Bonhoeffer’s final sermon, preached to these prisoners before his summons to Flossenburg, included a scripture passage from Isaiah 53 on the suffering servant and a text from 1 Peter 1 on the Christian’s living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ. This and the singing of “A Mighty Fortress” are dramatized, along with Bonhoeffer’s famous parting words to Payne Best: “This is the end, but for me the beginning of life” (54:15).

Here Ferdinand Schlingensiepen provides a bold theological interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s execution: “Terrible as this story is, it was not without God’s commands. And Bonhoeffer knew that himself. He says, ‘Hitler cannot kill me. The hour of my death will be prescribed by the living God himself.’ And he almost escaped in Schönberg, with the others. But God allowed him to become a martyr, which made him a much more important figure for future times” (54:35).

Keith Clements explains that Bonhoeffer’s court-martial was a sham, a hasty process not meeting proper judicial standards. As the film dramatizes Bonhoeffer’s final moments, including his shaming by an SS officer and his hanging, the film shows only his feet, while cross-cutting to a typewriter tapping out the death section of Bonhoeffer’s “Stages of Freedom” poem. Clements then reflects thoughtfully on Bonhoeffer’s execution: “When the tyrant executes the martyr, the tyrant’s power ends, because he can’t do any more than that. But the power of the martyr begins, because his witness goes on forever. … [These resisters] were the people who won the battle of faith and courage and conviction and human dignity. And it’s to them that we now look today” (59:40).

The film ends with a dramatization of the memorial service for Bonhoeffer and Bishop George Bell’s sermon, including the section in which Bell makes meaning of the German theologian’s martyrdom: “He represents both the resistance of the believing soul, in the name of God, to the assault of evil, and also the moral and political revolt of the human conscience against injustice and cruelty” (1:04:10).

While the film seems to question the results of Delmer’s black propaganda (including the execution of German civilians who listened to the broadcasts and the creation of the myth of the good German soldier), it sums up Bonhoeffer by noting that, “In death, as in life, Bonhoeffer has remained on the edge of controversy. Nonetheless, his writings and life have gradually been embraced by millions and many scholars have marveled at the breadth of his theological and philosophical appeal” (1:06:36). Short descriptions of the fate of other main characters are also provided at the close of the film.

On the whole, the film does well where it dramatizes the events of Bonhoeffer’s final years using his own words or those of other key figures who knew him. The contributions of Schlingensiepen and Clements are also informative and thought-provoking. Less coherent is the story of Sefton Delmer’s black propaganda unit, which oscillates between humour and pathos. The film interprets it both as vitally important to Allied victory and as a misguided effort.

Whether these two stories—that of Delmer’s black propaganda unit and of the final stages of Bonhoeffer’s life—actually belong in the same film is probably up for debate. The person of Otto John is the link between the two, but he plays only a minor part in the film. While Come Before Winter captures something of the power of Bonhoeffer’s martyrdom, in terms of an introduction to the German Resistance, I would still recommend Hava Kohav Beller’s fine documentary The Restless Conscience: Resistance to Hitler in Nazi Germany (docurama films, 1991), and for an introduction to Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the significance of his life, thought, and death, I would turn to the Martin Doblmeier documentary Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Pacifist, Nazi Resister (First Run Features, 2003).