Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 1 (March 2021)

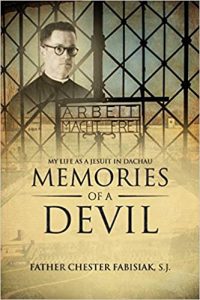

Review of Father Chester Fabisiak, S.J., Memories of a Devil: My Life as a Jesuit in Dachau (Coppell, TX: Dr. Danuta B. Fabisiak, 2018). 430 Pp. ISBN: 978-1732117006.

By Beth A. Griech-Polelle, Pacific Lutheran University

Eight prisons, two forced labor camps, and finally, Dachau Concentration Camp. The young, newly ordained Jesuit priest, Father Chester Fabisiak, endured all of this between September 1939 and April 1945 when Dachau was liberated by Allied Forces. Father Fabisiak then continued his path as a Jesuit priest, serving for nearly twenty years in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, then serving another thirty more years in the United States of America. Arguably, the bulk of his adulthood was spent in relative freedom abroad, yet this memoir limits itself to the most dramatic and life-threatening aspects of what was then a young man’s experiences.

After the war’s end, Father Fabisiak was working as a missionary in Bolivia. There, many people expressed their curiosity about “the Phenomenon,” or, as we call it, the Holocaust. The Polish priest served as a living witness to the events his parishioners had only heard about over radio broadcasts or had read in newspapers. And many of them were skeptical: could such atrocities have truly been committed by human beings? How could something so obscene as the Holocaust have been possible? This reluctance to accept what had happened inspired Fabisiak to write down his experiences—not out of hatred for the enemy, but as a way of showing readers what human beings are capable of doing to one another. Each chapter is very brief, written like a vignette, allowing readers to move easily from one terrifying experience to the next. All of this was written with the intent of documenting the truth of Father Fabisiak’s fate when he was in the hands of the Nazis.

After the war’s end, Father Fabisiak was working as a missionary in Bolivia. There, many people expressed their curiosity about “the Phenomenon,” or, as we call it, the Holocaust. The Polish priest served as a living witness to the events his parishioners had only heard about over radio broadcasts or had read in newspapers. And many of them were skeptical: could such atrocities have truly been committed by human beings? How could something so obscene as the Holocaust have been possible? This reluctance to accept what had happened inspired Fabisiak to write down his experiences—not out of hatred for the enemy, but as a way of showing readers what human beings are capable of doing to one another. Each chapter is very brief, written like a vignette, allowing readers to move easily from one terrifying experience to the next. All of this was written with the intent of documenting the truth of Father Fabisiak’s fate when he was in the hands of the Nazis.

When war broke over Poland on 1 September 1939, the young Chester Fabisiak went repeatedly to volunteer to fight for his nation. His conscription was rejected each time, as his eyesight was terrible. He was warned by various people, including his ophthalmologist, that he should flee the city of Poznan and go into hiding. However, the young man had been ordained a Jesuit priest and his superior ordered all of the priests to stay put. The Superior believed wholeheartedly that Germans were so cultured, so well-educated and so sophisticated that they would not harm the Jesuits. This trust was misplaced and soon enough the Jesuits’ home was being plundered by the occupying authorities. Before the end of September, the brothers living in the Jesuit home had been arrested and their residence had been turned into an office of the Gestapo.

After being transported from the initial jail cell in Poznan, thirteen of the brothers were placed in homes that Jewish families had occupied. The Nazis took away the Jewish families and imprisoned the priests in two separate homes. From what Fabisiak could deduce, the Nazis had no idea what to do with their captive priests, so they left them in the two homes, under guard, but provided no food whatsoever. Father Fabisiak, through good fortune, was allowed to step out onto the back patio for a time when he heard a Polish woman’s voice asking if the priests needed food. She threw bread and sausages over the fence, also providing Fabisiak with the town’s name (Golina). The woman’s brave act of generosity saved the lives of the priests. Fabisiak, strengthened from the food, decided to take action to provide for his “family.” He made runs out of the house for food, which he then divided and delivered to the priests living in both houses. One of his brothers referred to Fabisiak as “more dangerous than the devil himself.” (19) Fabisiak, reflecting back on that comment, added, “but he did not know that one day this dangerous devil would be his salvation.” (20) This type of action, of risking his own life for the sake of others, served as a hallmark of Father Fabisiak throughout the rest of his life despite the allusions to being a devil.

Other prison transfers followed, with Father Fabisiak describing in detail the craven acts of his captors—Austrians, Volksdeutsche, and Poles, but his account also focuses on the stories of assistance granted to him and the other Jesuits. There were times when Fabisiak was able to walk around somewhat freely, yet in a country occupied by Germans, it was only a matter of time before his freedom was taken from him once again. At one point, after being on the run, Fabisiak was denounced by a young Polish girl. He was accused of impersonating an ethnic German and ended up being interrogated by the Gestapo. As he was enduring a brutal whipping, Fabisiak came to realize the strength of his own character, refusing to utter a single word. For his insolence and refusal to cooperate with the Gestapo, the young priest was labelled as a thief and was sent to yet another cell awaiting his appearance before a judge.

Fabisiak’s account of the “trial” reveals the farce that Justice had become. His lawyer was not allowed to speak in his defense, the judge had already decided that Fabisiak was a thief and a liar, and so the sentencing was brief: off to serve an indeterminate time in a work camp, then on to a concentration camp. This led to yet another transfer to a jail in Zachthaus-Sieradz in 1940. During his time in Zachthaus-Sieradz, Fabisiak provides portraits of the various inmates who touched his life while sharing cell #13. Again and again, Father Fabisiak relates how various inmates came to respect his skills at thwarting their captors, referring to the theme of being a devil. One foul inmate, the hardened Mario, once told Fabisiak, “I suspected that you were a bad man, but now I see you are a devil.” (82) Devil, or not, Fabisiak helped to provide news of the outside world and obtain food for his cellmates while working as a barber, then later, as a secretary to the chief in the prison. Because Fabisiak could write in German Gothic Script, his skills allowed him to move into a slightly better situation, with a new set of prison clothes and even shoes. When the chief was being transferred, he offered to transfer Fabisiak with him to continue his office work. The Gestapo, however, intervened, and placed Fabisiak in a transport of prisoners sentenced to a work force in Ostrow (in western Poland).

After serving only a brief time in Ostrow, Fabisiak was sent, with no shoes, to work on a farm in a town called Ronau. The work was brutal—the prisoners had summer attire on, most had no appropriate shoes and it was November. Forced to dig frozen soil, beaten by whips, the prisoners were further punished with reduced rations each time they failed to meet the expected quotas of the day. The chief German announced to the starving, overworked men, the cure: “Those who cannot work have no right to live.” (104) Fabisiak notes after this, “We had a choice: die a little later in the work camp or die instantly under the brutal blows and kicks of the chief…” (104) This workforce was then transferred to Kotzine where Fabisiak was reunited with the man he had worked for as a secretary. This chief became Fabisiak’s protector and this relationship saved Fabisiak’s life. He was exempted from the exhausting work of digging canals, and instead spent his days cutting wood into long sticks while he looked across a field of wildflowers to a forest.

With the forest being so tantalizing close, the prisoners often dreamt of running to the woods to escape. Two men did try to escape but both met their end—with the chief providing the grisly details of the capture, wounds, and execution of one of the men. Along with this horrifying experience, Fabisiak encountered a German soldier who claimed to be a pastor. The soldier-pastor had volunteered to join the army because he thought the sacrifices of being a missionary were not “worth it.” (123) He warned Fabisiak to stop being a priest, predicting that once the war had ended, “priests would no longer exist.” (123) In the pastor-soldier’s mind, the Germans would win the war, thus defeating Christianity. Then the new religion would be German culture, with Hitler as their God. (124) Following this vignette, Fabisiak recalls how local Volksdeutsche farmers would yell and throw rocks at the prisoners as they marched to and from work details. Fabisiak then muses, “Their feelings of German superiority had poisoned and separated these families from the rest of the world. From these houses, young men were being recruited into the German army. With such hatred toward other human beings, they were no longer Catholic families, or religious families of any kind. Hitler’s ideas had deeply penetrated them, promising universal control and complete superiority over any individuals unlucky enough to not belong to their race of ‘supermen.’ They were being cultivated to have brutal instincts and to annul any morality other than their own splendid future of being Germans.” (125-126)

At the beginning of 1941, Father Fabisiak was moved on Gestapo orders to a jail in the city of Lodz. Officials in the prison presented Fabisiak with a choice: sign a document which denied his Polish ancestry (and changed him to an ethnic German) albeit a German with a long list of immoral crimes attached to his name. Father Fabisiak, despite their threats and shoves, refused to deny his Polish heritage and so he was left to contemplate his fate in the prison. He explains how on each Saturday afternoon, the prison guards would come to the cells demanding that all Jews and priests present themselves. The prisoners who had been housed there understood that if a Jew or priest did present themselves, they would be taken out to a courtyard and forced to sing and dance and be mocked by their captors. Fabisiak recalls that those Saturday afternoons were filled with anxiety, not knowing whether one was going to be pulled out of their cell, and, he also remembers that the German guards took great delight in these humiliations, noting, “For the Germans, those were days that were entirely appropriate and natural, days when they could enjoy the suffering of innocent men and behave exactly like who they were: first-class demons.” (143)

On March 14, 1941 at 11:00 p.m. Father Fabisiak was put on a train from the hellish prison in Lodz. The prisoners were provided with a small loaf of bread and a little piece of cheese. Five people occupied the space; as there was not enough room for all five people to sit at the same time, they took turns sitting and standing. The group was guarded by a Polish guard, who often left their train door open to allow air in for the five prisoners. To Fabisiak and his fellow travelers, the trip had the air of a happy journey, believing that their next place of imprisonment might be better. The train stopped at Dachau and Fabisiak noted, “We were immediately converted from a group of men into a group of animals.” (149)

His depiction of the screaming of the guards, the blows hitting all of the prisoners, and the general chaos of the situation is palpable. Father Fabisiak takes his readers along with him into the bathhouse, where the men were stripped naked, shaved, hit with streams of icy cold water followed by the sting of disinfectant; the shivering, starving men were further humiliated by their guards. Then it was on to quarantine for two weeks, all while being punished and threatened by the block leader (kapo) whose only task was to instruct and intimidate the new prisoners in the life of the camp. Once the period of quarantine ended, Father Fabisiak was assigned to a barracks and to work details including constructing roads, assisting bricklayers, and shoveling snow without shovels; all of which further weakened him physically. As Fabisiak put it, he felt no need to work for Hitler, but the law of the camp was “One who does not work cannot live.” (177) Along the way Fabisiak befriended a Protestant pastor, a communist diehard, and many others who he vividly sketches for his readers.

As he details the ins and outs of how Dachau functioned from a prisoner’s perspective, Fabisiak’s willingness to take risks is amazing. He decided one day to slip through a window of an empty barracks, climb under the bunks and go to sleep. On another occasion he refused to say that he had had sexual relations with women (for the promise of gaining a cushy job) and despite his refusal and threats to beat him, he stayed true to his principles. He also never lost an opportunity when it presented itself; in one instance, after cleaning the soldiers’ room and collecting the leftover food from their breakfast, he was able to smuggle the bits of food back to the priests’ barracks. When the barrack’s kapo saw what Father Fabisiak had been able to bring back he remarked, “Some time ago, I heard you were a devil, and now I see you are worse than a devil.” (182) The kapo then smiled and let Prisoner 29697 go past him.

As the days passed in Dachau, Father Fabisiak shares bits and pieces of stories about the other inmates he encountered, seeking to capture the diversity of the prisoners housed in the camp. He details one of the Roma prisoners, the tireless work of inmates in the infirmary, his encounters with Russian POWs, an English POW, a Hungarian Jew, a Greek young man, a Jewish bread thief, etc. In each of these chapters, Fabisiak shares his shrewd insight into the character of each man, assessing where they stood in relationship to God (if at all), and how these experiences with such diverse men influenced his growth as a human being. One particularly moving story featured a Catholic German man, imprisoned for ten years in Dachau. Fellow prisoners organized a jubilee to mark the date of the man’s 10th year in prison. The old man cried, tears streaming down his face, and Fabisiak reflected on the event, noting, “Somehow, their hearts remained alive and unbroken.” (213) But, despite the positive sketches, Father Fabisiak did not shy away from sharing the brutal reality of the camp. This is underscored in his chapter about a very young Polish boy, Zbyszek, who having been in Dachau from a tender age, learned that he must kill other prisoners in order to survive himself. He had been trained to “care” for the ill, which in reality meant that he was to administer lethal injections to end a patient’s life. Zbyszek’s hatred of Polish priests brought out the worst of his character, shouting obscenities, never showing remorse for his brutality and certainly displaying that he had no conscience—until one day when Zbyszek administered a syringe to a young Italian man. As the young man died, he cried out for his mother in such a way that Zbyszek stood pale and petrified, softly saying, “I also have a mother.” (218) The young Polish “nurse with the syringe” disappeared from the infirmary that day, never to kill another patient again.

Fabisiak also provides the harsh details of the system of punishments at Dachau, the awful reality that the beatings and other punishments were public so that human suffering was a part of daily life in the camp. He also recalls the building of a new, mysterious building, that only later, once construction had ended, did the men who built the structure come to discover that they had built a gas chamber. Once the facility was complete, the only remaining piece of the puzzle was to test the chamber’s effectiveness. Twenty young men from one of the barracks were brought in, told that they were “lucky” because they were inaugurating the new bathhouse. Other prisoner-inmates continued to be experimented on in the gas chamber. Fabisiak recalls the arrival of many Italian-Jewish families rounded up by the Nazis, how the authorities lied to the unsuspecting Jews (who mistakenly believed that since Italy was an ally of Germany, nothing bad would happen to them), telling them to bring all of their valuables with them during the “evacuation.” Once the Jewish families realized what was happening, many panicked, swallowing as many of their valuables as they could. Fabisiak records, “The Jews were clever, but the Germans were relentless.” (250) What followed was a scene of drawn out terror, some Jews were taken for X-rays to detect if they had swallowed valuables, others were administered strong doses of laxatives. The Germans picked through feces to dig out any final valuables. “Once this process was complete, the Jews had no more value to the German nation…. Dispossessed of all their belongings and riches, they stopped being men and became Jewish dogs.” (251) The gas chamber would be the final stop for these families and countless other victims.

From his time in Dachau, Father Fabisiak’s depictions and reflections reveal his concern with living according to Christian principles and what can happen when mankind abandons those moral principles for the ideology of Social Darwinism and Nazism. At the time of Dachau’s liberation, 29 April 1945, Father Fabisiak noted that out of the 85 Polish priests he knew at the camp, only 30 were still alive. As the survivors were left to reconstruct their lives and try to search for some meaning of these years of terror and absolute brutality, one passage stands out. Father Fabisiak is remarking on the rapaciousness of the Germans, how they were not content to ransack everything that was of value, “they wanted torn laces, old shoes, worn utensils, clothing with holes, like a band of poor housewives trying to prepare a family breakfast ‘feast.’ They threw themselves over other people’s goods and their misery as if they were dying of hunger and thirst. I remember, at this time, the Lager Fuehrer Redwitz—a barrack boss who was somewhat kind and who watched over us—holding some of these useless objects in his hands and saying, “What the hell is this for?”[italics added] (264) Perhaps Redwitz’s question could be applied in a broader sense to the years of suffering at the hands of the Nazi regime: what the hell was it all for? Father Fabisiak, attempting to chronicle the years of torment, shows the reader who the real devils were and repeats his motto, “Live only for today, and be peaceful on this day.” That motto helped save Father Fabisiak and countless others he encountered on his journey.

Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site

DACHAU, GERMANY – APRIL 14: The gas chamber at Dachau inside the new crematorium, and it may have been tested on prisoners, but there was no large-scale murder of prisoners there, as Dachau was not a death camp on April 14, 2017 in Dachau, Germany. Dachau was the first Nazi concentration camp and began operation in 1933 by Heinrich Himmler to hold political prisoners, though it later expanded to include Jews, common criminals and foreign nationals. Prisoners lived in constant fear of brutal treatment and terror detention including standing cells, floggings, the so-called tree or pole hanging, and standing at attention for extremely long periods. The camps were liberated by U.S. forces on 29 April 1945. There were 32,000 documented deaths at the camp, and thousands that are undocumented. In the postwar years the Dachau facility served to hold SS soldiers awaiting trial. After 1948, it held ethnic Germans who had been expelled from eastern Europe and were awaiting resettlement, and also was used for a time as a United States military base during the occupation. It was finally closed in 1960. At the moment the facilities fulfill the function of Commemorative Museum. (Photo by Athanasios Gioumpasis/Getty Images)…seehttps://www.gettyimages.ca/detail/news-photo/the-gas-chamber-at-dachau-inside-the-new-crematorium-and-it-news-photo/674056850