Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 25, Number 4 (December 2019)

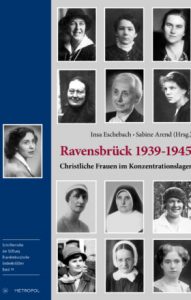

Review of Sabine Arend and Insa Eschebach, eds., Ravensbrück: Christliche Frauen im Konzentrationslager 1939-1945 (Berlin: Metropol, 2018). Pp. 294. ISBN: 9783863313821.

By Christina Matzen, University of Toronto

Ravensbrück: Christliche Frauen im Konzentrationslager 1939-1945 is an unconventional and significant tribute to the Christian women who were interned in the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp during World War II. Editors Sabine Arend and Insa Eschebach curated this volume as an accompaniment to the Ravensbrück Memorial’s 2017 exhibit on Christian prisoners, which was part of a German Evangelical Church Kirchentag event in Berlin. In the context of this exhibition, the term “Christian” is a category of self-description and encompasses women from Eastern and Western Europe. Indeed, this inclusive approach lies at the heart of the book’s strength. Through the contributors’ attention to women and their religious lives before and during their incarceration, women victims of Christian faith are rightly made more visible in the history of Nazi Germany, Christianity, gender, and memory.

Resistance is a central theme of the book. Christian women in Ravensbrück tended to be involved in opposition within charitable associations and in education but have long been regarded as “apolitical, inconspicuous, and therefore irrelevant,” helping to explain the marginal attention paid to this persecuted group in historical scholarship (21). Most forms of resistance from Christian women entailed critical statements against the German government and expressions of solidarity with people attacked by the Nazi regime. As Manfred Gailus writes in his contribution on Protestant resistors, many religious women found themselves in a dual position of opposition: they criticized both Nazism and sexist religious conventions (206).

Resistance is a central theme of the book. Christian women in Ravensbrück tended to be involved in opposition within charitable associations and in education but have long been regarded as “apolitical, inconspicuous, and therefore irrelevant,” helping to explain the marginal attention paid to this persecuted group in historical scholarship (21). Most forms of resistance from Christian women entailed critical statements against the German government and expressions of solidarity with people attacked by the Nazi regime. As Manfred Gailus writes in his contribution on Protestant resistors, many religious women found themselves in a dual position of opposition: they criticized both Nazism and sexist religious conventions (206).

Dr. Katharina Staritz is just one compelling woman chronicled in the book. Born in Breslau in 1903, Staritz became a member of the Confessing Church in 1934 and by 1938 was blessed as a vicar. Shortly after the November Pogrom, Staritz took over leadership of the Breslau branch of Protestant theologian Heinrich’s Grüber’s “auxiliary body for non-Aryan Christians,” a welfare agency to help Jews who had converted to Christianity emigrate safely in order to escape deportations. Although Staritz was forbidden as a female vicar to perform baptisms, she nonetheless baptized Jewish women. In September 1941 she wrote a circular to the Breslau clergy asking them not to exclude parishioners marked with a yellow star. The Gestapo confiscated the circular, labeled her as “Jewish friendly and objectionable,” and arrested her the following winter (25-26). Staritz wrote after the war that while she was interned in Ravensbrück, she worshiped the Bible every Sunday and preached to a small group of women as they walked up and down the camp road (155). With Claudia Koonz’s seminal work in mind on how women could be both victimized by the regime and complicit in the regime’s murderous policies, one might wonder to what extent Staritz—an oft-cited figure throughout the book—is representative of Christian women who served time in Ravensbrück. Her story is profound and important, but readers who approach this volume without some familiarity of the complex roles of both women and religious institutions in Nazi Germany may be left with an incomplete impression of the scope of Christian women’s actions in the Reich.

The book is organized in three parts and is largely based on survivor accounts and judicial and police records. Eschebach provides an introduction on the social and religious contexts of Christians in the Ravensbrück. The second (and largest) section of the book explores religious practices in concentration camps and chronicles the lives of thirteen women who, inspired by their religious views, opposed the Nazi regime and were consequently arrested and incarcerated in Ravensbrück. The final section comprises six essays that cover topics such as the experiences of women in various Christian sects that were represented in the Ravensbrück inmate population (namely Catholic, Protestant, and Jehovah’s Witness, but other groups are referenced as well), religious life in Fürstenberg and Ravensbrück during the Third Reich, and the role of church remembrance and memorial work.

Analytical contributions of the book are strongest in regard to Christian social life in Ravensbrück. The authors argue that ecumenical efforts in the camp had a limited impact, and Christian convictions seldom resulted in prisoners overcoming confessional differences, national origins, educational milieus, and politically and religiously motivated concepts of community and resistance. Language skills and class distinctions tended to inhibit communication among Christian women in Ravensbrück, and multinational and pan-Christian discussions were predominantly initiated by individuals. All prisoners lacked holy texts and liturgical objects, and although Ravensbrück camp regulations did not explicitly prohibit religious practice, large group meetings outside the barracks were prohibited, limiting the possibility of collective services. Women resorted to creative responses and generated booklets with Bible verses and psalms from stolen office papers. Women also used plastic and aluminum to fashion miniature crucifixes and pendants with depictions of saints. However, these common struggles did little to unify observant women who hailed from other countries and engaged in dissimilar Christian practices.

An innovative and empathetic blend of public history and traditional scholarship, this book’s discussion of women’s struggles within their religions, within Nazi-dominated Europe, and within the Ravensbrück concentration camp is commendable. Additional information and especially archival citations for the thirteen biographies would have strengthened the volume since this book will certainly be indispensable for those seeking a deeper knowledge of the particular denominations and individuals highlighted in the book. Ravensbrück: Christliche Frauen im Konzentrationslager 1939-1945 nevertheless is a forceful and insightful overview that will be of great interest to a wide readership.