Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 23, Number 3 (September 2017)

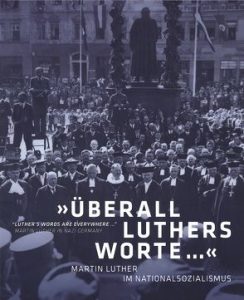

Review of Stiftung Topographie des Terrors and Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand, eds., “Überall Luthers Worte …” – Martin Luther im Nationalsozialismus (Berlin: Stiftung Topographie des Terrors, 2017). 271 Pp., ISBN 978-3-941772-33-5.

By Dirk Schuster, University of Potsdam

“Luther’s words are everywhere …” – this quote by Dietrich Bonhoeffer from 1937 correctly reflects the public perception of the Reformation Jubilee in Germany today. It is therefore hardly surprising that the Berlin Topography of Terror Documentation Center chose the words of Bonhoeffer as the title holder for an exhibition on Martin Luther in National Socialism, to be seen in Berlin from April 28 to November 5, 2017. The exhibition catalog illustrates impressively that there was a broad reception of Luther at the time of the Third Reich. The catalog is divided into three periods: the years 1933 to 1934, the period from 1935 to 1938, and the years of the Second World War. In addition, it offers seven essays by well-known scholars, which concisely and intelligibly summarize the current state of the research and, based mostly on the authors’ own work, the respective subject areas. At this point, the main criterion of the catalog can already be formulated. The documentation, including the introductory texts, is written in German and English, in contrast to the essays. These are only written in German with an English abstract. For an internationally renowned documentation center like the Topography of Terror, such an approach is somewhat incomprehensible. The German and English description of the presented objects emphasizes the intention to address an international audience against the backdrop of the Reformation Jubilee. Why this was not implemented with regards to the essays remains an open question and might irritate non-German speakers.

The first part of the catalog impressively illustrates the instrumentalization of Luther as the “German faith hero” in the first two years of the Third Reich by using photographs and covers of contemporary publications. Several Protestant representatives drew an additional historical and theological continuity line from Luther to Hitler. Publications and celebrations such as the 450th anniversary of the reformer in 1933and the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Bible translation in 1934 illustrate the reference to Luther at this time. Likewise, many new church buildings were named after the reformer, the most well-known example being the Martin Luther Memorial Church in Berlin-Mariendorf, consecrated in 1935. On the theological level, in the early years of the Nazi regime, Luther’s doctrine of the two kingdoms was the center of church-political debates concerning the relationship between the church and the state. But this was increasingly changing in the mid-1930s. As a result of the exclusion of the Jews forced by the National Socialists, Luther’s antisemitic “Jewish writings” were increasingly placed at the center of the reformer’s reception. These writings often served as justification for the persecution of the Jews from a theological point of view. It is somewhat surprising that the section on the state-church relationship is mainly related to the view of the National Socialists, Bonhoeffer, Niemöller, and other representatives of the Confessing Church. The German Christians with their theological line of continuity of Jesus-Luther-Hitler are hardly mentioned in this section.

The first part of the catalog impressively illustrates the instrumentalization of Luther as the “German faith hero” in the first two years of the Third Reich by using photographs and covers of contemporary publications. Several Protestant representatives drew an additional historical and theological continuity line from Luther to Hitler. Publications and celebrations such as the 450th anniversary of the reformer in 1933and the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the Bible translation in 1934 illustrate the reference to Luther at this time. Likewise, many new church buildings were named after the reformer, the most well-known example being the Martin Luther Memorial Church in Berlin-Mariendorf, consecrated in 1935. On the theological level, in the early years of the Nazi regime, Luther’s doctrine of the two kingdoms was the center of church-political debates concerning the relationship between the church and the state. But this was increasingly changing in the mid-1930s. As a result of the exclusion of the Jews forced by the National Socialists, Luther’s antisemitic “Jewish writings” were increasingly placed at the center of the reformer’s reception. These writings often served as justification for the persecution of the Jews from a theological point of view. It is somewhat surprising that the section on the state-church relationship is mainly related to the view of the National Socialists, Bonhoeffer, Niemöller, and other representatives of the Confessing Church. The German Christians with their theological line of continuity of Jesus-Luther-Hitler are hardly mentioned in this section.

Chapter 2 illustrates the legitimacy of the antisemitism of the National Socialists by the German Christians, using the example of the pamphlet by the Thuringian regional bishop, Martin Sasse. In his preface, Sasse referred to the connection between Luther’s birthday on November 10 and the November pogroms in Germany of 1938, in order to present Luther as the greatest antisemite of his time, who had always warned against the Jews (p.118 f.).

Chapter 3 deals with references to Luther in the Second World War. The first section shows documents and pictures, including clergymen who stylized Luther as the heroic leader in their war sermons, even though there was no comparable war enthusiasm among church representatives as there had been in 1914. A separate sub-chapter is about the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life, which was founded by Protestant regional churches on May 6, 1939, and which Susannah Heschel addressed in her highly-respected book, The Aryan Jesus. [1] The documents and books presented in the catalog clearly illustrate how this institute was intended to create a “German” Christianity and thus to complete Luther’s “unfinished” reformation, as Walter Grundmann, the director of the institute, pointed out in his opening lecture in 1939.[2]

The seven essays at the end of the catalog summarize the current state of research on Protestantism in Germany from the Kaiserreich to the Third Reich in compressed form. Hartmut Lehmann shows that Luther was already formed into a German hero in the Kaiserreich. Together with “völkisch” patterns of thought, the idea arose that the German people were meant to have a special destiny in the world. Heinrich Assel, on the other hand, addressed the inner-theological discourses on the Lutheran heritage at the beginning of the 1930s, which were often characterized by the acceptance of an authoritarian leadership state. Beate Rossié, Stefanie Endlich, and Monica Geyler-von Bernus describe the different Lutheran images in the Third Reich, whereby the German Christians, in the sense of the Nation-Socialist point of view, linked Luther with combat. Cornelia Brinkmann on hymnal reforms and Manfred Gailus on the reception of Luther’s Jewish writings show once again that not only the German Christians used Luther. Representatives of the so-called intact regional churches, as well as representatives of the Confessing Church, also developed antisemitic reform ideas these areas. Olaf Blaschke still devotes himself to the “well-intentioned antisemitism” in Catholicism at the background of National Socialism, and Peter Steinbach treats the churches’ dealings with their own guilt and responsibility after 1945.

The catalog, which reproduces the printed parts but not the contents of the listening stations in the exhibition, is a very good example of the present-day public discussion about the church in National Socialism. Scholars who are familiar with the subject won’t find anything new, but this is not the aim of such an exhibition. The exhibits, and above all, the documents, photographs, and books, show how Luther was instrumentalized more than 400 years after his Reformation. If you cannot visit the exhibition, which can be seen until November 5, 2017, in Berlin, this very good exhibition catalog can be recommended.

[1] Susannah Heschel, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008).

[2] Walter Grundmann, Die Entjudung des religiösen Lebens als Aufgabe Deutscher Theologie und Kirche (Weimar 1939).

Excellent and substantive review.

Thanks very much!