Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 19, Number 1 (March 2013)

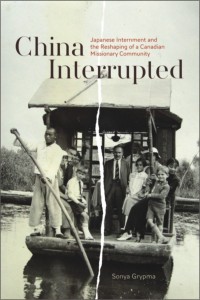

Review of Sonya Grypma, China Interrupted. Japanese Internment and the Reshaping of a Canadian Missionary Community (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012), xvi + 305 Pp., ISBN 9781554586451.

By John S. Conway, University of British Columbia

It is surely regrettable that the considerable contributions made by the Canadian churches to the early twentieth century missionary endeavours are now largely forgotten, or in some cases deplored as an example of “imperialist cultural aggression.” In fact, a hundred years ago, in proportion to their size and resources, the churches of Canada sponsored more missionaries at home and abroad than any other nation. The young men and women who volunteered their services were responding to the popular call for “the evangelization of the world in this generation.” China was the preferred destination, and indeed became the flagship of European and North American missionary expansionism.

It is surely regrettable that the considerable contributions made by the Canadian churches to the early twentieth century missionary endeavours are now largely forgotten, or in some cases deplored as an example of “imperialist cultural aggression.” In fact, a hundred years ago, in proportion to their size and resources, the churches of Canada sponsored more missionaries at home and abroad than any other nation. The young men and women who volunteered their services were responding to the popular call for “the evangelization of the world in this generation.” China was the preferred destination, and indeed became the flagship of European and North American missionary expansionism.

This proved to be a short-lived endeavour, spanning only from 1890 to 1950. It was both rewarding and life-threatening. In 1900 the Boxer Rebellion forced many missionaries to flee from their postings. In 1926 a similar political turmoil led to a widespread, if temporary, evacuation. But the most serious challenge came after the Japanese had occupied much of eastern China. When war broke out in December 1941, all those missionaries, like other British, Canadian, American and Dutch civilians, who had chosen to remain at their posts, were interned for the duration of hostilities.

Sonya Grypma is a professor of nursing in British Columbia, and her interest was drawn to a small coterie of half a dozen Canadian missionary nurses who were interned for nearly four years in exceedingly horrendous and degrading conditions. Her account is based on the surprising amount of survivors’ personal and written records which she has blended into a convincing narrative and commentary. Though necessarily focusing on these interned nurses and their partners, she seeks to place their experiences in the wider context of mission history. She regrets that the closure of the North China Mission as a result of the civil war and communist take-over in 1949 triggered a silencing of the historical record and only helped to keep the tragedy of internment from Canadian public attention. This silence was deepened by the fact that no Japanese apology or reparation was offered to these interned civilians. Grypma’s study is therefore a most welcome corrective and one which throws light on this small but significant episode in Canadian Church history.

Her account is also notable in that she carefully avoids the kind of hagiographic treatment so often found in missionary histories. Instead, she adopts a warmly sensitive but critical evaluation of the sufferings endured, particularly by the women internees. She rightly notes that the majority of these Canadian nurses were “mishkids”, that is, they were the children of missionaries who had gone out to China a generation before. These women had been born and brought up in China, but returned to Canada for their professional training. Their decision to return to China in the late 1930s was their response to the call for nurses, so urgently needed throughout China, in the same spirit that had inspired their parents. Nursing was a chance to return to the land of their birth. Also, Grypma surmises, they hoped to find amongst the eligible bachelors in the mission field a refined and dedicated partner. Indeed many did.

The younger missionaries were impatient with the pietistic approach of their parents. They believed that practical service was as effective a witness as preaching. They were also more sensitive than their elders to the consequences of western imperialist exploitation of China. At the same time they enjoyed living comfortably in the mission compounds. They were not free from the paternalistic mentality of doing good to their charges, with whom they did not much socialize. Even though the missionary cohort was upheld by its sense of compassion for the poor and sick, until internment they had had no direct experiences of the humiliations and poverty of China’s millions.

When the war broke out in Europe in 1939, China seemed relatively calm. In 1940 when Godfrey and Betty Gale were married near the missionaries’ seaside resort, life seemed very pleasant. But in 1941 the situation in Asia grew much tenser. The consular offices urged women and children to be repatriated before it was too late. Betty Gale, now expecting a baby, was undecided. She packed her trunks, but then unpacked them again. To stay meant increased risk; to depart guaranteed loneliness. Her colleague Florence Liddell decided to take her two children back to Canada, but could not tell when she and Eric, the Olympic champion runner, would be reunited. In fact, they never were. Eric died of a brain tumour in February 1945, still in captivity. But Betty determined that she would stay and support Godfrey, in the hope that their marriage would be enhanced even in such terrible times. It was a choice she never regretted—at least in public. Instead she claimed that the years of internment had provided a test of their character and perseverance. It was a difficult but invaluable opportunity to understand God’s purposes for their lives.

The first few months after Pearl Harbor saw the missionaries confined to their quarters, though they were still able to have the services of a Chinese cook. But in September 1942, when they were moved to Shanghai, their expectations that they would be repatriated were dashed, even though Betty’s missionary father was one of the lucky ones. They had to recognize that an internment camp was as much of a mission field as anywhere else, though their forbearance was sorely tried when they were placed along with hundreds of the snobbish and wealthy Shanghai internees, who made no secret of their hostility and even contempt for missionaries. They had difficulty shaking the perception that they were bizarre creatures eager to evangelize. Conditions were stark; the dirty and contaminated buildings were infested with insects. While Godfrey was called on to treat patients, Betty sought ways to escape some of the more repulsive aspects of camp lie by busying herself with care of their daughter. She was even able to take up some nursing duties.

Their final two years were spent in even more pernicious conditions in the bomb-damaged, rat-infested warehouse of Pudong Camp across the river from Shanghai’s Bund. As the Japanese prospects for victory faded, so conditions for their prisoners only grew worse. By 1945, bombing raids on Shanghai were an incessant danger. But even more ominous was the shortage of food, as was the effect on their health of the complete lack of privacy. The facilities were sparse, dirty and cold. In this camp, the internee population was more crude, aggressive and at times violent. As camp physician, Godfrey was in constant demand. But even his strength was sorely weakened by an attack of tuberculosis, which was to take many years to heal. The lethal negligence of the Japanese authorities undoubtedly contributed to the deaths of thousands throughout the internment camp system.

Despite all, Betty Gale sought to make the camp “a happy place” for the children. She brought to the task the resources of the Christian tradition for seeing suffering as a redemptive experience. By such means she resisted victimization and defeat. And after liberation she never engaged in recrimination. Her faith enabled her to come to terms with the meaning of the disasters she and her colleagues had endured.

Grypma’s account of the harrowing experiences of these missionary nurses adds further details to the magnificently comprehensive study by Greg Leck, Captives of Empire: The Japanese Internment of Allied Civilians in China, 1941-1945 (Bangor, PA: Shandy Press, 2006). Her achievement is both to bring alive the personal dimensions of these families, as well as to analyze the wider setting of their China years. China, for them, was a place where committed Christians went to live out their faith in tangible ways. In the 1940s the internment camps became social laboratories for testing the Christian principles of kindness and long-suffering under the most trying conditions. The interruption of this dedicated service was a deplorable and cruel disaster. And it was equally regrettable that, for these missionaries, the opportunity to return to complete their years of service never occurred again. But we can be grateful to Sonya Grypma that she has so capably laid out for us the record of these young Canadians’ service overseas, and had broken through the veil of silence which has for so many years prevented their story from being better known.

Greetings. In the introduction of this review, I read this sentence: “In fact, a hundred years ago, in proportion to their size and resources, the churches of Canada sponsored more missionaries at home and abroad than any other nation.”

What is the source of this information?

Hello Albert! I believe John Conway would have obtained this information from the introduction of China Interrupted.

My own source for this claim is the work of Alvyn Austin – particularly his books Saving China (U Toronto, 1986, p. 85) and Canadian Missionaries at Home and Abroad (U Toronto, 2005, p. 4).