Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 25, Number 2 (June 2019)

Article Note: Heath Spencer, “The Thuringian Volkskirchenbund, the Nazi Revolution, and Völkisch Conceptions of Christianity,” Church History 87, no. 4 (December 2018): 1091-1118.

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

Recently, Heath Spencer of Seattle University has been investigating the connections and disconnections between German liberal Protestant thought and Nazi conceptions of Christianity. In this article, he tackles the question of why prominent Thuringian liberal Protestants in the Volkskirchenbund (People’s Church League) supported the pro-Nazi Deutsche Christen (German Christians) in the German church elections of July 1933. He argues that ideological affinity between the Volkskirchenbund and the German Christians was less important than pragmatic and strategic considerations, and that these liberal Protestants only supported German Christians reluctantly, once other options had been exhausted. “Their story,” Spencer writes, “illustrates one of the more complicated paths toward Christian complicity in the Third Reich” (1092).

The episode around which Spencer’s article revolves was the decision of the Volkskirchenbund—a liberal faction in the Thuringian Protestant synod—not to run their own candidates in the July 1933 church election, but rather to recommend to their members that they vote for the list of candidates put forward by the German Christian Movement, the leading pro-Nazi faction. The result was that the Volkskirchenbund disappeared from the synod and became a study group (Arbeitsgemeinschaft), while the German Christians went on to capture 46 of the 51 seats in the synod and proceeded to make Thuringia a bastion of Nazi Protestantism.

Spencer critiques the view offered by Karl Barth and promulgated by members of the theologically conservative Confessing Church that the rise of the German Christian Movement was the product of two centuries of theological modernism. Thuringian Volkskirchenbund leaders, he suggests, “did not rush into the arms of the Deutsche Christen in July 1933; anxiety and resignation were prominent alongside of cautious optimism and occasional expressions of enthusiasm” (1094).

Tracing Thuringian church politics from 1918-1933, Spencer argues that the Thuringian church constitution of 1924 gave rise to diverse church-political factions, including the Volkskirchenbund, which represented the political left, over and against the right-leaning Lutheran Christliche Volksbund (Christian People’s League) and the centrist Einigungsbund (Unification League). The Volkskirchenbund aligned itself with other German liberal Protestants who “called for democratic governance, theological pluralism, and churches that stood above political parties and narrow class interests—all key elements of the liberal Protestant Volkskirche ideal” (1098). Heinrich Weinel (professor of New Testament in Jena) was a key figure in the Volkskirchenbund, working with other liberal Protestant leaders to advocate for modern theology, innovative adult education programs, and interdenominational elementary schools to broaden the reach of liberal Protestantism (and liberal politics) in the region.

After 1924, however, both Thuringian parliamentary politics and church politics became more conservative. In the Protestant synod, the rise of leftist Religious Socialists was matched by the emergence of a new völkisch group, Bund für Deutsche Kirche (League for German Church), which began introducing “church legislation that promoted racial purity, hardline nationalism, and the removal of ‘Jewish elements’ from Christianity” (1105). Because liberals in the Volkskirchenbund promoted theological pluralism, they professed openness towards both these new groups. Indeed, Heinrich Weinel and others became increasingly engaged with the Christian-völkisch movement in Thuringia, combining “gestures of toleration, criticism of ‘excesses,’ and partial affirmation” in their responses, even proving willing to “recognize race and nation as the God-given foundations of all human life and all human love,” as Weinel put it (1106).

By the beginning of the 1930s, as the völkisch movement grew dramatically in both the Thuringian state and church, the Volkskirchenbund (now led by Hans Heyn) remained open to it as an important expression of Christianity among German people, criticizing only those aspects that liberals deemed overly divisive, including some of the anti-Jewish elements of the Bund für Deutsche Kirche.

Ultimately, though, a völkisch wing emerged within the Volkskirchenbund itself, particularly among younger members who were animated by the ways in which German racial nationalism seemed to unite society and church. By the time of the Nazi seizure of power and the 1933 church elections, four new developments pushed the Volkskirchenbund to capitulate to völkisch Protestantism: the rise of the German Christian Movement, which polled strongly in the January 1933 church elections; the frustration of Volkskirchenbund leaders over their failure to attract more younger followers; their fear that theological conservatives would seize control and make Thuringia too sectarian; and their lack of money to run a proper campaign in the July 1933 church elections (1111-1112). In the end, leaders in the Volkskirchenbund decided that the German Christians best represented the church-political goals of the Volkskirchenbund, sent around an official announcement of their support for the pro-Nazi Protestants, and effectively closed up shop on their own movement.

Spencer’s article illuminates the way theological liberals in the Volkskirchenbund—committed to pluralism and unity—brought themselves to support the German Christian Movement. They hoped to ensure that the church did not miss its chance to “to rescue an embattled and divided nation, to remedy the mistakes of the past” and “to meet the needs of the hour” (1118). “Ironically, their dream of a free, democratic, and culturally relevant Volkskirche led them to support—at least momentarily—an authoritarian group determined to impose its militant and racist ideology on the church and its members” (1118).

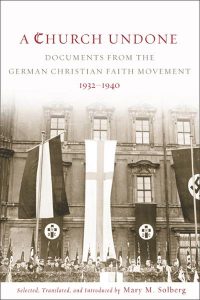

Despite the excellent contributions of such authors as James Zabel, Doris Bergen and Robert Ericksen, Solberg feels that “far too few people in or out of the academy know far too little“ about the conduct of the churches In Hitler’s Germany. But her extended introduction clearly indicates her approach to answering the questions posed by her documents: specifically what role did this German Christian Faith Movement play in the wider picture; how successful or significant were its supporters in the rise and maintenance of Nazism, at least up to 1940; and how should Christians and churches today learn from this example of a church undone? Her skillful translations of the writings of several prominent members of this movement will be of considerable value to those who do not read German, but it would have been helpful to have a biographical note or appendix outlining the careers of these authors. Her conclusion is that this was not a unique episode, that the conflation of political, racist and nationalist ideas with theological witness is a constant temptation, and therefore that the German experience in the 1930s deserves further study by both theologians and historians.

Despite the excellent contributions of such authors as James Zabel, Doris Bergen and Robert Ericksen, Solberg feels that “far too few people in or out of the academy know far too little“ about the conduct of the churches In Hitler’s Germany. But her extended introduction clearly indicates her approach to answering the questions posed by her documents: specifically what role did this German Christian Faith Movement play in the wider picture; how successful or significant were its supporters in the rise and maintenance of Nazism, at least up to 1940; and how should Christians and churches today learn from this example of a church undone? Her skillful translations of the writings of several prominent members of this movement will be of considerable value to those who do not read German, but it would have been helpful to have a biographical note or appendix outlining the careers of these authors. Her conclusion is that this was not a unique episode, that the conflation of political, racist and nationalist ideas with theological witness is a constant temptation, and therefore that the German experience in the 1930s deserves further study by both theologians and historians.