Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 31, Number 1 (Spring 2025)

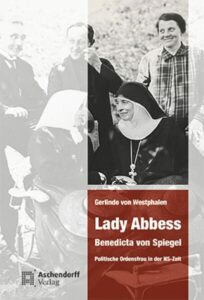

Review of Gerlinde von Westphalen, Lady Abbess. Benedicta von Spiegel—Politische Ordensfrau in der NS-Zeit. Münster: Aschendorff Verlag, 2022.

By Martina Cucchiara, Bluffton University

In over five hundred pages, this hefty biography traces the life and leadership of Abbess Benedicta von Spiegel, who led the Benedictine abbey of St. Walburg in Eichstätt for nearly twenty-five years, from 1926 until her death in 1950. While the title emphasizes the Nazi period, the strength of the book lies in the rich account of von Spiegel’s entire eventful life that straddled two centuries and included her troubled time in two other cloisters before ultimately settling at St. Walburg.

Born Elisabeth Agnes Wilhelmine Klementine Freiin von Spiegel in January 1874, the young noblewoman grew up in wealth and privilege alongside her eight siblings on the family’s vast estate in East Westphalia. The Catholic von Spiegel family, whose lineage dates to at least the fourteenth century, maintained a close and enduring connection to the Church. In many ways, this book is as much a history of the von Spiegel family as it is a biography of Benedicta von Spiegel. Readers interested in the German aristocracy will gain considerable insights, into not only intimate family relationships revealed through von Spiegel’s extensive personal correspondence, but also the immense influence that the nobility still wielded in twentieth-century Germany and considered their birthright.

At the age of twenty-five, von Spiegel entered the contemplative Benedictine abbey of Maredret in Belgium, where she took vows two years later and received the religious name Benedicta. In 1914, after the outbreak of war, she moved to the German abbey of St. Hildegard in Eibingen in the Rhineland before finally settling at St. Walburg in Bavaria in 1918. Unlike apostolic congregations of Catholic sisters, which focus on teaching, nursing, and social work, nuns like the Benedictines are dedicated primarily to prayer.[1] These communities typically observe more demanding monastic rules than apostolic congregations, including strict claustration. During von Spiegel’s tenure at at St. Hildegard, for example, nuns were prohibited from leaving the cloister even for necessary medical treatment.

During the eighteen years that von Spiegel spent at Maredret and St. Hildegard, she struggled profoundly with her vocation and appeared to experience several extended episodes of mental illness, though any retrospective diagnosis remains uncertain. Additionally, she seems to have faced serious conflicts with the abbess of St. Hildegard, who doubted her religious calling and described her as a burden to the community and as “severely affected” (erheblich belastet) (p. 112). The latter longed to remove her from the abbey. Despite limited documentation, von Westphalen presents a nuanced discussion of these struggles, offering readers rare insight into the inner workings of contemplative cloisters and the deeply personal challenges of an individual nun. Von Spiegel’s extensive correspondence with her spiritual advisors, including her Belgian confessor Columba Marmion, sheds light on how she and her mentors sought to address these crises within the framework of strong mystical beliefs. The letters reference “invisible beings” and, at one point, even suggest the possibility of an exorcism (pp. 78, 81). The author’s exploration of von Spiegel’s deep mystical affinities is a valuable contribution to the scholarship on modern religious women, a field that too often neglects the significance of mysticism, spirituality, and religious experience. Many readers will likely wish to learn more about practices such as the annual rite of the miraculous oil at St. Walburg (Walburgisöl) or the use of the rite of exorcism in the modern Catholic Church.

Von Spiegel’s affinity for mysticism perhaps explains her long and close friendship with the famous stigmatic Therese Neumann of Konnersreuth (1898–1962), whom von Spiegel met some years after her move to the abbey St. Walburg in 1918. There she finally found a permanent home, becoming abbess only eight years after her arrival. The abbey grew considerable under her leadership, not least because she transformed it into a thriving religious community devoted to the fine and decorative arts. Von Spiegel also interpreted the rule of claustration in a very liberal manner and frequently left the cloister to travel or visit friends in the local community. This newfound freedom enabled her to forge close friendships with a circle of Catholic intellectuals in Eichstätt, which included the journalist Fritz Gerlich, the Capuchin priest Ingert Naab, the aristocrat Erich Fürst Waldburg-Zeil, and the theology professors Franz Xaver Wutz and Joseph Lechner. Von Spiegel, an intellectual in her own right who spoke several languages, thrived in this environment. Therese Neumann, who hailed from a modest peasant milieu and lacked a formal education, became an important member of this circle.

Neumann remains of considerable interest to scholars, and von Westphalen dedicates an entire chapter to her friendship with von Spiegel. After experiencing visions and stigmata—the spontaneous appearance of wounds resembling those of Christ—for the first time in 1926, Neumann quickly rose to fame as a Catholic mystic, drawing both admiration and skepticism. Her claim that she neither ate nor drank anything for years, except for a single consecrated host per day, invited considerably suspicion and scorn, especially since she refused to undergo a clinical observation to verify her claim. The author asserts that she has uncovered new evidence proving that Neumann’s close circle of friends and influential churchmen were aware of her fraud regarding her eating habits and even helped to cover it up. The key piece of evidence is a letter from May 1938 written by Joseph Lechner, a confidant of von Spiegel, in which he suggested subjecting Neumann to a controlled clinical observation, albeit under the condition that the results would be sealed and deposited in the Vatican. He writes that the Cardinal Secretary of State and future Pope Pius XII, Eugenio Pacelli, agreed to this arrangement. Von Westphalen notes that this “unattainable so-called proof under lock and key” in the Vatican “would have made Therese Neumann more or less untouchable” (p. 202). Although no direct evidence exists in which von Spiegel and her associates explicitly acknowledged knowing about (and abetting) Neumann’s fraud, the author infers that they actively supported it because “Therese Neumann had long since become a symbol of unwavering Catholic resistance” in Nazi Germany (p. 13).

The theme of resistance is central to von Westphalen’s narrative of von Spiegel’s conduct under Nazism. She argues that the abbess was “political and engaged in the resistance against National Socialism” (p. 9). However, this assertion is problematic, not least because of the lack of a clear definition of resistance. It is evident, however, that von Westphalen does not define resistance as total opposition to the regime that involved concrete actions to bring about its downfall. Von Spiegel’s life certainly was deeply affected by violence when her close friend Fritz Gerlich was arrested in 1933 and later executed during the Röhm Putsch in 1934 for his anti-Nazi writings in the newspaper Der Gerade Weg. However, von Spiegel herself did not take part in these journalistic efforts. Instead, her actions in Nazi Germany were entirely in line with those of Catholic Church leaders at the time who adhered to a cautious and conciliatory policy, which primarily sought to preserve Catholic institutions. From time to time, von Spiegel engaged in what Martin Broszat termed Resistenz, meaning nonconformist behavior that aimed at preserving pre-1933 values without directly confronting the Nazi regime. This was the case during the school struggle in the mid-1930s, when the Bavarian state dismissed women religious teachers from public schools and commenced the closure of Catholic secondary schools. Von Spiegel wrote lengthy (and ultimately futile) protests to Nazi officials, but this was not at all unusual or even all that political.

Moreover, the book’s broad scope makes it difficult to explore certain critical topics in sufficient depth. The foreign-exchange trials of 1935–36, which directly affected von Spiegel and St. Walburg, were pivotal moments in the regime’s campaign against religious congregations and orders. Yet the author devotes less than a page to them. Similarly, von Westphalen cites part of a 1990 local news report claiming that St. Walburg had sheltered “a person persecuted by the SS,” but offers no further context or corroboration (p. 404). Where the book truly excels is in its rich portrayal of von Spiegel’s family history. The detailed accounts of her siblings, nieces, and nephews—each following different paths in the Third Reich—provide a compelling snapshot of one aristocratic Catholic family navigating Nazi Germany. The book’s greatest strength lies in its ability to illuminate the intimate world of one woman and her family, offering a deeply personal lens on history.

Notes:

[1] Benedictine nuns follow the Rule of St. Benedict (6th century). Their communities are typically autonomous and focus on contemplative life and liturgical prayer within a cloistered setting. Catholic sisters usually follow the rule of St. Augustine. They usually practice limited or no enclosure and are dedicated to apostolic work in their communities, including teaching, nursing, and social work. See: Relinde Meiwes, “Arbeiterinnen des Herrn”. Katholische Frauenkingregationen im 19. Jahrhundert (Frankfurt: Campus, 2000), 52–67.