Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 27, Number 2 (June 2021)

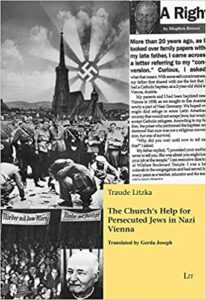

Review of Traude Litzka, The Church’s Help for Persecuted Jews in Nazi Vienna, trans. Gerda Joseph (Wien: LIT Verlag, 2018). 159 Pp. ISBN: 978-3-643-91036-3.

By Beth A. Griech-Polelle, Pacific Lutheran University

Traude Litzka’s work, in some respects, might be misleading in its title. The Church’s Help for Persecuted Jews in Nazi Vienna does not quite speak to the contents of the volume. Instead, it might have been more helpful to title the book, The Church’s Help for Those Persecuted as Jews in Nazi Vienna. In this way, readers would perhaps recognize the signal that many of the individuals who risked their lives to protect other people in danger were focused, at least at first, on saving those individuals who had been baptized as Roman Catholics and were, therefore, according to the theology of the Church, no longer Jews, but Catholics. Later in Litzka’s work, Jews who had not been baptized were also helped—to the credit of the team of rescuers operating in Vienna. Her book serves as a reminder to historians that the fate of the “non-Aryan Catholics” still needs to be further researched. Her work also reveals the enormous difficulties in conducting such research as so many rescue operations had to be enacted through verbal orders in an effort to evade Gestapo and other denouncers’ attempts to thwart the life-saving activities.

Despite the challenges of locating survivors and documents which would testify to the actions of the brave Catholic men and women engaged in rescue work, Litzka has assembled quite a roster of both individuals as well as orders of religious who decided that, despite the threat of arrest, interrogation, and imprisonment (or worse), their consciences would not allow them to remain inactive in the face of overwhelming discrimination and hardships. One such man who figures prominently throughout the book is the Jesuit priest, Ludger Born (born in Duisburg in 1897). Born was appointed as head of the “Aid Office for Non-Aryan Catholics” by Cardinal Theodor Innitzer in 1940 and for the next five years, Father Born worked assiduously to aid all those who needed help. He inherited his position from another priest, Father Georg Bichlmair, who had established the office and had staffed it primarily with dedicated women. Some of these women’s stories were later documented after the war by Father Born, providing some insight into both their identity and motivations. Out of the twenty-three employees, Father Born’s documentation focused on only five of the female workers. He attributed their dedication to their profound religiosity.

Despite the challenges of locating survivors and documents which would testify to the actions of the brave Catholic men and women engaged in rescue work, Litzka has assembled quite a roster of both individuals as well as orders of religious who decided that, despite the threat of arrest, interrogation, and imprisonment (or worse), their consciences would not allow them to remain inactive in the face of overwhelming discrimination and hardships. One such man who figures prominently throughout the book is the Jesuit priest, Ludger Born (born in Duisburg in 1897). Born was appointed as head of the “Aid Office for Non-Aryan Catholics” by Cardinal Theodor Innitzer in 1940 and for the next five years, Father Born worked assiduously to aid all those who needed help. He inherited his position from another priest, Father Georg Bichlmair, who had established the office and had staffed it primarily with dedicated women. Some of these women’s stories were later documented after the war by Father Born, providing some insight into both their identity and motivations. Out of the twenty-three employees, Father Born’s documentation focused on only five of the female workers. He attributed their dedication to their profound religiosity.

What exactly did the Aid Office for Non-Aryan Catholics do? At first, when the Nazis marched into Austria, Cardinal Innitzer was friendly towards the Hitler regime. However, by July 1938 he had reconsidered his conciliatory position, as the Nazis shuttered all Catholic schools, dissolved Catholic libraries, forbade Catholic orders from providing instruction, and expropriated abbeys and other houses of orders, expelling and harassing priests and nuns (129). At that point, the Cardinal determined it was time to assist victims of Nazism and he worked personally with both Father Bichlmair and Father Born to establish the Aid Office, often donating his own money and material goods to help the organization. At first, the Aid Office focused on assisting Jews who had been baptized into the Catholic faith and much of Litzka’s primary source documentation attests to this focus. She also emphasizes that, according to the teaching of the Church at that point in time, there was still a great deal of anti-Judaism and suspicion of converted Jews, even though the Church’s focus was on saving Jewish souls through conversion.

While in the early years a number of Jews sought conversion motivated by a genuine interest in Christianity, as time went on and conditions worsened, Father Born and his staff began to realize that some Jews sought baptism as a way of easing emigration problems (some countries such as Brazil favored Catholics in their immigration policy). However, as the persecutions and discriminations increased in quantity and in severity, the Aid Office and priests in Vienna began baptizing large numbers of Jews, recognizing that a baptismal certificate might be a life-saving measure rather than a marker of the true conversion of souls. After the war began, a baptismal certificate did not generally assist in saving someone from being persecuted as a “non-Aryan of Jewish descent” and the number of requests for baptisms of Jews declined sharply.

There were different types of assistance that the Aid Office offered to the persecuted. The staff did not request to see “proof” of baptismal certificates and were therefore open to aiding unconverted Jews as well as “non-Aryan Catholics.” Workers at the Aid Office initially assisted with the emigration process, providing advice and assistance with the complicated bureaucratic red tape to obtain visas, affidavits, and passports. Once emigration became less and less likely for the persecuted, the Aid Office began functioning as a social welfare agency. Staff visited the persecuted in their overcrowded apartments, procuring food, medical supplies, and even dentures (!). They served as a lifeline for those who were being deported to places such as Theresienstadt, mailing parcels with food and sometimes clothing and monitoring the postcards that arrived from each deportee. The system they established, helping victims of persecution, was even more poignant when one realizes that many of the women who worked in the Aid Office were themselves categorized as “non-Aryan Catholics” and some of them were deported as well.

In addition to offering spiritual comfort and material aid, workers in the Aid Office and other Catholic institutions also sought to hide the persecuted in various ways. In one such situation, Dominican nuns in Vienna-Hacking had retreated to Kemmelbach, which was located along a river and could be developed agriculturally. The sisters worked the farm and raised animals—but they also hid Jews on the premises:

During the most dangerous period for them, they had been hidden and fed for three weeks…. 25 Jews were hidden between the two ceilings (of the pigpen). The oxcart took them to St. Pölten, where they were placed with a farmer. He was happy that he could use them as laborers. Sr. Antonia and Mrs. Reichel, afraid of the Russians, went to Vienna with the Jews. The Jews continued on to their home in Hungary. (83)

The order’s chronicle then adds the fascinating twist to the end of the story—as the Russians advanced, Sr. Antonia and Mrs. Reichel were in turn saved by the Jews they had originally rescued.

A Jewish woman disguised Sr. Antonia and Mrs. Reichl—who were the most threatened by the Russians—and took them along as “her daughters”…. One morning at 4 a.m., the bell at the gate rang, and a Jew delivered “girls” who were marked with a Jewish star. (83)

In this way, one life-saving kindness had been returned.

Litzka also included less than flattering reasons for some religious to take in frightened Jews. In the case of the Carmelite Sisters of Töllergasse, Born’s reports reveal that the sisters first motivation to get involved with non-Aryan Catholics was from a monetary desire. They needed to pay off a debt and in their chronicle they openly admit that they took in individuals who “donated” jewelry, which the nuns used to purchase a monstrance. They also apparently accepted gold from their wards. Unlike the Dominican nuns mentioned above, the Carmelite nuns seemed to have profited monetarily from their relief efforts. As Litzka states, “Independently of whether the donation of their jewelry was truly ‘willingly’ and based on gratitude, the suggestion for ‘gold donation’ and then even more the acceptance of these donations, appears to be exploitation in a hopeless situation” (87).

This publication is to be commended for attempting to uncover the untold stories of assistance given in Vienna by religious men and women. The book itself is somewhat choppy in its presentation of anti-Judaism and only devotes limited space to discussions of the role of Pope Pius XI and Pius XII in influencing (or not) the desire on the part of Catholics to aid “non-Aryan Catholics” as well as full Jews in their time of greatest need. There are some minor errors, including the misspelling of Margarete Sommer’s name, but these are only minor points considering the number of chronicles and other accounts the author had to search through in order to compile the examples contained in the work. In the final analysis, Litzka who considers all of the many reasons why there has been such silence about the attempted rescue operations in Vienna concludes, “At least one thing is certain: In those times, there were unquestionably more individuals who clandestinely assisted but who even afterwards did not want to ‘make a big deal of it’—which is why we learn of it only rarely or incidentally (131)”. Litzka is to be commended for her dedication to uncovering these stories so that they are not lost forever.