Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 20, Number 3 (September 2014)

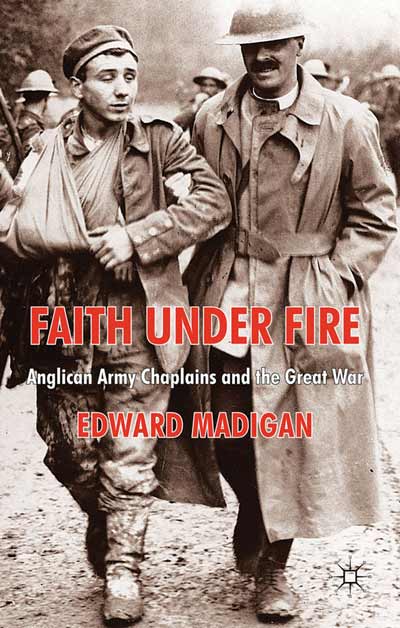

Edward Madigan, Faith under Fire: Anglican Army Chaplains and the Great War (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). Ix+296 Pp. ISBN 978-0-230-23745-2.

By John S. Conway, University of British Columbia

The first casualty of the Great War, beginning in August 1914, was the wave of patriotic enthusiasm, which led thousands of men, in all European countries, to volunteer for active combat. They expected that the conflict would be short, sharp and victorious, and that they would be home by Christmas. They had also been led to believe that victory would be theirs because God was on their side. But when the fighting began in the muddy fields of Flanders, the resulting death and devastation was disillusioning both militarily and spiritually. For many, if not for most of these eager recruits, one of the salient consequences was that the credibility of the Christian gospel, as preached by the army chaplains, was tested and often found wanting.

Edward Madigan’s valuable study begins with a comprehensive survey of the literature about chaplains and their war-time contributions, some written by chaplains themselves, such a Ernest Raymond’s Tell England, or the far more influential novel by Robert Graves, Goodbye to all That. Many of these books presented a largely negative picture of the war records of these chaplains, finding that they were generally not respected by either officers or men, being considered inadequate to the tasks they faced.

Edward Madigan’s valuable study begins with a comprehensive survey of the literature about chaplains and their war-time contributions, some written by chaplains themselves, such a Ernest Raymond’s Tell England, or the far more influential novel by Robert Graves, Goodbye to all That. Many of these books presented a largely negative picture of the war records of these chaplains, finding that they were generally not respected by either officers or men, being considered inadequate to the tasks they faced.

Such critical, or even cynical, assessments in the post-war period only accelerated the decline in the fortunes of the Church of England, which has since proved irreversible. Madigan’s book seeks to examine more closely how far these pejorative judgments are supported by the surviving archival sources.

In his view, the Anglican chaplaincy service was handicapped from the beginning by serious obstacles, both civilian and military. The War Office, to be sure, had an establishment of a Chaplain-General–a Presbyterian–with a limited staff of regular army officers. But the Army High Command thought in terms of a short, mobile professional-conducted campaign, and were therefore reluctant to have the services of any non-combatants anywhere near the front lines. They were unwelcoming of the large number of civilian clergy–and amateur soldiers–who now offered their services as volunteer chaplains. As such, they would have to be given officer status, which meant that each would have to be provided with a servant, a horse, a groom, and space for extra luggage, not to mention basic food and shelter, but none of whom would actually do any shooting. As such they were seen as an unaffordable luxury whose number were best kept to a minimum.

At the same time, the Church of England bishops were reluctant to release men from their parish duties to undertake military activities, for which, despite their eagerness, they had no training. The bishops held that participation in front-line fighting contradicted not only the Ten Commandments but also their ordination vows. Very obviously, none of these potential chaplains had any pastoral experience of war-time conditions, and most had lost touch with the generation of young men, especially from the working classes. Their status as officers, and their clerical training mostly as university graduates, created social barriers which limited their effectiveness. Furthermore, the Army’s reluctance to let them get anywhere near the front lines was a cause for resentment among the troops. They were often relegated to rear echelons or hospitals, and were often suspected of being too lily-livered to actually fight. In these same rear areas, these clergymen were often confronted with restless, sex-starved soldiers, who were eager enough to sample the military-established or at least-tolerated brothels as a relief from the deadly dangers of the trenches. The chaplains’ pious exhortations to maintain standards of decency often fell on deaf, mocking ears.

Only slowly did the War Office realize the value of the chaplains’ contributions to building and maintaining morale, or appreciate their pastoral care for the wounded or the dying. But the chaplains themselves often felt they remained outsiders. Their high hopes that the Church’s witness to the troops, and its evident support for the war effort, would lead to a large-scale return to church worship and attendance were to be sadly disappointed. The example set by many chaplains of diligent and inspiring service was not enough to staunch the post-war ebbing away of the Church’s following, or to reverse the war-induced skepticism about the Church’s message.

As Madigan makes clear, many of the chaplains themselves entertained unrealistic expectations. They had had no previous exposure to the dehumanizing effects of battle combat, so their idealistic optimism was easily shattered. They were unprepared to meet the difficult circumstances in which their religious ministrations were often rejected or regarded as irrelevant. The majority of the troops demonstrated apathy, indifference or even hostility to organized religion. The army’s compulsory church parades were particularly resented. There was little or no sign of any spiritual revival. Such conditions presented an acute challenge which few chaplains were able to deal with successfully.

The result was often loneliness and isolation, making it hard for the chaplains to get alongside the men in the ranks. The situation was only reinforced by the lack of training for service among men under intense moral and physical stress. Only in the later stages of the war were these defects overcome, but they did little to tackle the wider questions about the incompatibility of war itself with the Christian gospel.

Madigan does his best to amend the pejorative views of the chaplains’ services as expressed in later memoirs. He produces the evidence of laudatory testimonies from their superior officers, and points to the number of chaplain decorated for their war-time accomplishments. But he is obliged to note that while many chaplains were respected and well-liked, this was in spite of, not because of their status as priests and representatives of the Established Church. He also notes that their hard-hewn skills at providing comfort and inspiring courage in front-line troops were qualities not much in demand in post-war Britain.

The fact was that the horrors, tensions and bloodshed on the battlefields destroyed faith in a beneficent God for many men, including chaplains. They were overcome by the atmosphere of death and devastation, and adopted a grim fatalism, which made more bearable the impotence and insignificance of the individual soldier. And yet, Madigan points to the unspoken, virtually unrecognized fact that many soldiers adhered to an “essential” or “unconscious” Christianity and to deep-seated beliefs in the goodness of man. It was these manifestations of self-sacrifice, fraternity, charity and humility which enabled them to cope with the strains of trench warfare. It was a vague but real faith.

After the Armistice, the veterans returned home and were treated as heroes. But Britain was far from being a place fit for heroes to live in. The reforms in both church and state which many chaplains longed for never came. There was much disillusionment. But, in his final chapter, Madigan describes some of the more progressive initiatives arising from the chaplains’ war experiences. Dick Sheppard at St Martin’s-in–the-Field in Trafalgar Square, “Tubby” Clayton and his Toc H fraternity, Studdert Kennedy and his Industrial Christian Fellowship, and William Temple and the Life and Liberty Movement, evoked new and reforming images of the serving church. These post-war social service organizations owed much to the former chaplains’ charisma, and were testimony of their founders’ determination to improve the lot of their fellow combatants. They now had the advantage of a much improved familiarity with working-class men, and an enhanced sympathy for their interests and welfare. These contributions were not therefore just to the Church but to society as a whole.

In Madigan’s view, the negative representations of chaplains in post-war literature seem unwarranted and biased. His book will undoubtedly help to dispel the myth of insincere or cowardly parsons, who indulged in un-Christian demonization or preached hatred of the enemy. Instead he tells the story of chaplains who ministered effectively to men in extreme conditions, and who drew from these experiences the strength to serve both church and state in their post-war careers.