Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 26, Number 1/2 (June 2020)

Multi-Media Note: “The Danger of Indifference: ‘Then They Came for Me,’” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Facebook Live Presentation, June 10, 2020

By Kyle Jantzen, Ambrose University

During the coronavirus pandemic, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has been broadcasting online presentations over Facebook Live. On June 10, historian Edna Friedberg hosted one of these events, which featured Dr. Suzanne Brown-Fleming Director, International Academic Programs at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (and member of the editorial board of Contemporary Church History Quarterly).

In the wake of the George Floyd killing and subsequent anti-racism protests, many people have turned to a famous quotation on the final wall of the museum’s permanent exhibition—a quotation by the German Protestant pastor Martin Niemöller:

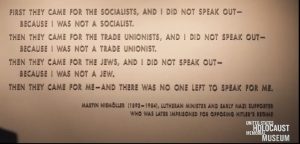

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Friedberg asked Brown-Fleming to discuss the origins of the quotation, along with the man behind it. Brown-Fleming, a historian of the churches in the Nazi era, began by explaining that Germany was transformed quite quickly from a liberal democracy to a dictatorship, in part because the German society didn’t resist the emerging Nazi threat. This lack of empathy was an important factor in the Holocaust. People didn’t speak out about the persecution of the Jews because it didn’t seem like their problem.

After remarking on the power, universality, and timelessness of the Niemöller quotation Brown-Fleming explained how Niemöller—though he is often held up as an opponent of Nazism—began as a supporter of the Hitler movement. Born into a monarchic, nationalist home, he served as a naval officer during the First World War and also held the typical antisemitic stereotypes of his day, seeing Jews as the Christ-killers and as outsiders in German society. Niemöller voted for the Nazis in several elections between 1924 and 1933 and read Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf. He resonated with Nazism and believed Hitler could bring God and country together into a powerful union.

After remarking on the power, universality, and timelessness of the Niemöller quotation Brown-Fleming explained how Niemöller—though he is often held up as an opponent of Nazism—began as a supporter of the Hitler movement. Born into a monarchic, nationalist home, he served as a naval officer during the First World War and also held the typical antisemitic stereotypes of his day, seeing Jews as the Christ-killers and as outsiders in German society. Niemöller voted for the Nazis in several elections between 1924 and 1933 and read Hitler’s book, Mein Kampf. He resonated with Nazism and believed Hitler could bring God and country together into a powerful union.

Niemöller broke with the Nazi Party once he saw that it began to interfere with Protestant Church life, and reacted strongly against its distortions of Christian belief, including its racialization of the message of salvation and its challenge to the identity of Jewish converts to Christianity. By 1934, he led the Confessing Church movement, which the Nazis saw as an opposition movement. When Niemöller and other clergy met with leading Nazis that year, he found that he had become an enemy of the state. Niemöller’s status within Germany and internationally made him a prominent dissident. Arrested several times for his outspoken preaching, he was held as Hitler’s personal prisoner from 1937 to 1939, first in the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp and then, from 1941, in the Dachau Concentration Camp.

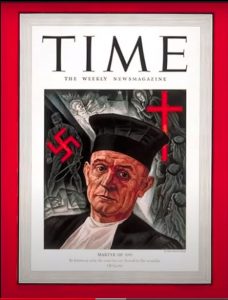

Time magazine featured Niemöller on its cover in 1940, as a symbol of the church, which it described as the sole domestic opponent to Nazism. Indeed, as Brown-Fleming explained, people from all around the world prayed for Niemöller and sent letters to him in the concentration camp.

Time magazine featured Niemöller on its cover in 1940, as a symbol of the church, which it described as the sole domestic opponent to Nazism. Indeed, as Brown-Fleming explained, people from all around the world prayed for Niemöller and sent letters to him in the concentration camp.

Even though Niemöller was a prisoner in Nazi concentration camps, however, he remained a German nationalist and even attempted to enlist in the German navy in 1939, when the war began. He also retained the antisemitic beliefs which had appeared in his sermons in the mid-1930s. As an example, Brown-Fleming discussed a 1935 quotation from one of Niemöller’s sermons, in which he described the Jews as “a highly gifted people which produces idea after idea for the benefit of the world, but whatever it takes up changes into poison, and all that Judaism ever reaps is contempt and hatred.” After the war, Niemöller even accused American occupation authorities of being influenced by vengeful Jews in the military.

Just after the war, though, in the winter of 1945, Niemöller took his wife Else back to Dachau to show her where he had been incarcerated. There, they saw a crude sign which declared that 200,000 people had been cremated at Dachau between 1933 and 1945. This devastated him, knowing that he had done nothing about this from 1933 until 1937, during the time when he had been free in Nazi Germany.

He soon began to speak publicly about the issue, stating in an October 1945 speech, “We are guilty of having been silent when we should have spoken.” He built on that speech and eventually it developed into the famous quotation.

Brown-Fleming explained Niemöller as a complex figure. He was courageous. He mistook the Nazis for something they weren’t, but it took virtually the entire Nazi era to understand the depths of Nazi depravity. A person of conscience, his realization of Nazi criminality began to change him. He grew into a committed pacifist and internationalist and let go of some of his antisemitism as well.

His famous quotation developed over time, and there was never one authoritative version. Rather, Niemöller adapted it for the various audiences before whom he spoke and used it widely in his American speaking tour in 1947.

Brown-Fleming closed with some thoughts about combatting antisemitism. She reiterated that Niemoller was a complex figure, that he held beliefs that were clearly wrong—beliefs which led to the deaths of six million Jews. Yet she also finds him to be a representative of hope, stating, “All of us can look at him an see that we’re all imperfect and yet we call all do something. We all have a voice and we can change.”

Friedberg closed the presentation with a tribute to Officer Stephen Tyrone Johns, the USHMM security guard killed while by an antisemitic extremist while on duty in June 2009.

The Facebook live event can be viewed on the USHMM YouTube channel.